<Back to Index>

- Physicist Walter Houser Brattain, 1902

- Author Boris Leonidovich Pasternak, 1890

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1894

PAGE SPONSOR

Maurice Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, OM, PC (10 February 1894 – 29 December 1986) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 10 January 1957 to 18 October 1963.

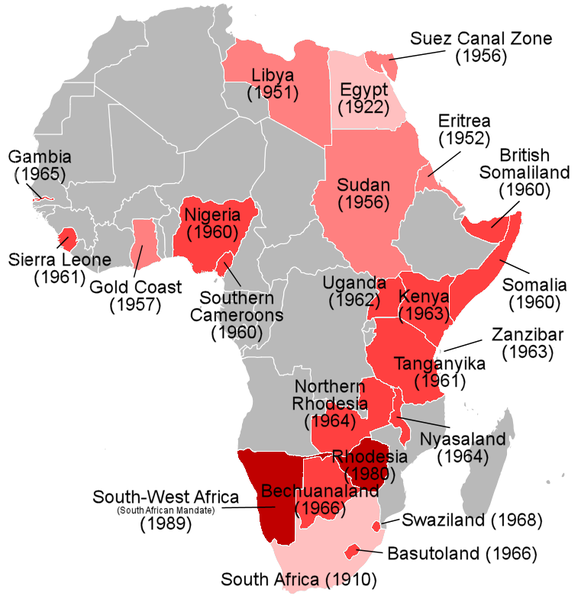

Nicknamed 'Supermac' and known for his pragmatism, wit and unflappability, Macmillan achieved notoriety before the Second World War as a Tory radical and critic of appeasement. Rising to high office as a protegé of wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill, he believed in the essential decency of the post-war settlement and the necessity of a mixed economy, and in his premiership pursued corporatist policies to develop the domestic market as the engine of growth. As a One Nation Tory of the Disraelian tradition, haunted by memories of the Great Depression, he championed a Keynesian strategy of public investment to maintain demand, winning a second term in 1959 on an electioneering budget. Benefiting from favourable international conditions, he presided over an age of affluence, marked by low unemployment and high if uneven growth. In his Bedford speech of July 1957 he told the nation they had 'never had it so good', but warned of the dangers of inflation, summing up the fragile prosperity of the 1950s. In international affairs Macmillan rebuilt the special relationship with the United States from the wreckage of Suez, and redrew the world map by decolonising sub-Saharan Africa. Reconfiguring the nation's defences to meet the realities of the nuclear age, he ended National Service, strengthened the nuclear deterrent by acquiring Polaris, and pioneered the Nuclear Test Ban with the United States and the Soviet Union. Belatedly recognising the dangers of strategic dependence, he sought a new role for Britain in Europe, but his unwillingness to disclose United States nuclear secrets to France contributed to a French veto of the United Kingdom's entry into the European Economic Community. Macmillan's government in its final year was rocked by the Vassall and Profumo scandals, which seemed to symbolise for the rebellious youth of the 1960s the moral decay of the British establishment. Resigning prematurely after a medical misdiagnosis, Macmillan lived out a long retirement as an elder statesman of global stature. He was as trenchant a critic of his successors in his old age as he had been of his predecessors in his youth. When asked what represented the greatest challenge for a statesman, Macmillan replied: 'Events, my dear boy, events'.

Harold Macmillan was born at 52 Cadogan Place in Chelsea,

London, to Maurice Crawford Macmillan (1853 – 1936), publisher, and

Helen (Nellie) Artie Tarleton Belles (1856 – 1937), artist and

socialite, from Spencer, Indiana, US. He had two brothers, Daniel, eight years his senior, and Arthur, four years his senior. His paternal grandfather, Daniel MacMillan (1813 – 1857), was the son of a Scottish crofter who founded Macmillan Publishers. Macmillan's

early education was intense and closely guided by his American mother.

He was taught French at home every morning by a succession of nursery

maids, and exercised daily at Mr Macpherson's Gymnasium and Dancing

Academy, around the corner from the family home in Cadogan Place. From

the age of six or seven he received introductory lessons in classical

Latin and Greek at Mr Gladstone's day school, close by in Sloane Square. Macmillan then attended Summer Fields School, Oxford (1903-6), but his time at Eton (1906-10)

was blighted by recurrent illness, starting with a near-fatal attack of

pneumonia in his first half; he missed his final year after being

invalided out, and had to be taught at home by private tutors (1910-11), notably Ronald Knox, who did much to instil his High Church Anglicanism. He went up to Balliol College, Oxford (1912-14), where he obtained a First in Mods (Latin and Greek, the first half of the four-year Oxford Greats course), and became an officer of the Oxford Union Society, before the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

Macmillan served with distinction as a captain in the Grenadier Guards during the war, and was wounded on three occasions. During the Battle of the Somme, he spent an entire day wounded and lying in a slit trench with a bullet in his pelvis, reading the classical Greek playwright Aeschylus in the original language. Macmillan

spent the final two years of the war in hospital undergoing a long

series of operations, and saw no further active service. His

hip wound took four years to heal completely, and left him with a

slight shuffle to his walk (and a limp grip in his right hand from a

separate hand wound) for the rest of his life. As was common for

contemporary former officers, he continued to be known as 'Captain

Macmillan' until the early 1930s. Of the 28 freshmen who started at Balliol with Macmillan, only he and one other survived.

Macmillan lost so many of his fellow students during the war that afterwards he refused to return to Oxford, saying the university would never be the same. According

to his entry in Who's Who (1987) he obtained "1st. Class Hon.

Moderations 1919", suggesting that he was awarded a degree in absentia.

He served instead in Ottawa, Canada, in 1919 as ADC to Victor Cavendish, 9th Duke of Devonshire, then Governor General of Canada and future father-in-law.

On

his return to London in 1920 he joined the family firm Macmillan

Publishers as a junior partner, remaining with the company until his appointment to ministerial office in 1940. Macmillan married Lady Dorothy Cavendish, daughter of the 9th Duke of Devonshire, on 21 April 1920. Her great-uncle was Spencer Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire, who was leader of the Liberal Party in the 1870s, and a close colleague of William Ewart Gladstone, Joseph Chamberlain and Lord Salisbury. Lady Dorothy was also descended from William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, who served as Prime Minister from 1756 – 1757 in communion with Newcastle and Pitt the Elder. Her nephew William Cavendish, Marquess of Hartington married Kathleen, a sister of John F. Kennedy. Between 1929 and 1935 Lady Dorothy had a long affair with the Conservative politician Robert Boothby,

in full public view of Westminster and established society. Boothby was

widely rumoured to have been the father of Macmillan's youngest

daughter Sarah. The stress caused by this may have contributed to

Macmillan's nervous breakdown in 1931. Lady Dorothy died on 21 May 1966, aged 65. The Macmillans had four children: Maurice Macmillan, Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden (1921 – 1984), Lady Caroline Faber (born 1923), Lady Catherine Amery (1926 – 1991) and Sarah Macmillan (1930 – 1970). On 26 November 1950, Lady Dorothy's brother Edward Cavendish, the 10th Duke of Devonshire had a heart attack and died in the presence of John Bodkin Adams, the suspected serial killer. Thirteen days before, Edith Alice Morrell,

another patient of Adams, had also died. Adams was tried in 1957 for

her murder but controversially acquitted. Political interference has

been suspected and indeed, the case was prosecuted by a member of Macmillan's cabinet, Sir Reginald Manningham-Buller. Home office pathologist Francis Camps linked Adams to a total of 163 suspicious deaths. Eileen Kathleen O'Casey (née Reynolds), the actress wife of Irish dramatist Seán O'Casey,

had a close relationship with Macmillan, who had published her

husband’s plays. There is disagreement over whether he proposed after

she was widowed. According to her husband's biographer: 'Eileen and

O'Casey's marriage had become celibate by the time she was in her

fifties, now a strikingly handsome woman, notable for her warm wit,

who, on her own candid admission, fulfilled her sexual needs outside

marriage ... One ardent, lifelong admirer was Macmillan, who in later

life gently broached to her the idea of marriage, which she declined.' Eileen's obituary notice in the Evening Standard states:

'It was the death of Sean O'Casey in 1964, and of Dorothy Macmillan,

two years later, that cemented Macmillan and Eileen’s intimacy. She

became the light which illuminated his prime years, eventually even

replacing Dorothy in his affections.' O'Casey's

biographer notes that 'Eileen was the first woman whom Macmillan asked

to sit in Lady Dorothy’s place at table in Birch Grove; he also took

her out frequently to dine at Buck’s Club.' Eileen's obituary in The Times records

that 'she became one of Harold Macmillan's closest friends. The two

grew even closer after the death of their respective spouses. That

Macmillan never proposed marriage was a source of bewilderment to

outsiders, although Eileen was understanding about his shyness .... Her

relationship with Macmillan, which only ended with his death in 1986,

was a source of comfort to her in old age. For his part, he relied

completely on her honest, outspoken Irish perspective. She recalled one

lunch when Lord Home asked Macmillan to accept a peerage: "Harold

turned to me and said 'What about that Eileen?' I told him I thought it

nicer to keep the name Harold Macmillan to the end of his days and

said, 'Titles are two-a-penny these days. Butchers and bakers and

candlestick makers are all getting them.' I got the impression that Alec Home was a bit annoyed with me."

Elected to the House of Commons in 1924 for the depressed northern industrial constituency of Stockton-on-Tees, Macmillan lost his seat in 1929 in the face of high regional unemployment, but returned in 1931. He spent the 1930s on the backbenches, with his championing of economic planning, anti-appeasement ideals and sharp criticism of Stanley Baldwin and Neville Chamberlain serving to isolate him from the party leadership. During this time (1938) he published the first edition of his book The Middle Way, which advocated a broadly centrist political philosophy both domestically and internationally. In the Second World War Macmillan at last attained office, serving in the wartime coalition government as the Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Supply from 1940 to 1942. The task of the department was to provide armaments and other equipment to the British Army and Royal Air Force. Macmillan travelled up and down the country to co-ordinate production, working with some success under Lord Beaverbrook to increase the supply and quality of armoured vehicles. Macmillan was appointed as Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies in 1942, in his own words, 'leaving a madhouse in order to enter a mausoleum'. Though a junior minister he was sworn of the Privy Council and spoke in the House of Commons for successive Colonial Secretaries Lord Moyne and Lord Cranborne.

Macmillan was given responsibility for increasing colonial production

and trade, and signalled the future direction of British policy when in

June 1942 he declared: As minister resident with a roving commission, Macmillan also the minister advising General Keightley of V Corps, the senior Allied commander in Austria responsible for Operation Keelhaul, which included the forced repatriation of up to 70,000 prisoners of war to the Soviet Union and Tito's Yugoslavia in

1945. The deportations and Macmillan's involvement later became a

source of controversy because of the harsh treatment meted out to Nazi collaborators and anti-partisans by the receiving countries, and because in the confusion V Corps went beyond the terms agreed at Yalta and AFHQ directives by repatriating 4000 White Russian troops and 11,000 civilian family members who could not properly be regarded as Soviet citizens.

Macmillan returned to England after the European war and was Secretary of State for Air for

two months in Churchill's caretaker government, 'much of which was

taken up in electioneering', there being 'nothing much to be done in

the way of forward planning'. He felt himself 'almost a stranger at home', and lost his seat in the landslide Labour victory of 1945, but soon returned to Parliament in a November 1945 by-election in Bromley.

With the Conservative victory in 1951 Macmillan became Minister of Housing under

Churchill, who entrusted Macmillan with fulfilling the latter's

conference promise to build 300,000 houses per year. 'It is a gamble —

it

will make or mar your political career,' Churchill said, 'but every

humble home will bless your name if you succeed.' Macmillan achieved the target a year ahead of schedule. Macmillan served as Minister of Defence from October 1954, but found his authority restricted by Churchill's personal involvement. In the opinion of The Economist:

'He gave the impression that his own undoubted capacity for imaginative

running of his own show melted way when an august superior was

breathing down his neck.' A

major theme of Macmillan's tenure at Defence was the ministry's growing

reliance on the nuclear deterrent, in the view of some critics, to the

detriment of conventional forces. The Defence White Paper of February 1955, announcing the decision to produce the hydrogen bomb, received bipartisan support. By this time Macmillan had lost the wire-rimmed glasses, toothy grin and brylcreemed hair

of wartime photographs, and instead grew his hair thick and glossy, had

his teeth capped and walked with the ramrod bearing of a former Guards

officer — acquiring the distinguished appearance of his later career. Macmillan served as Foreign Secretary in April - December 1955 in the government of Anthony Eden. Returning from the Geneva Summit of that year he made headlines by declaring: 'There ain’t gonna be no war.' Of the role of Foreign Secretary Macmillan famously observed: Anthony

Eden resigned in January 1957. At that time the Conservative Party had

no formal mechanism for selecting a new leader, effectively leaving the

choice of the new leader, and Prime Minister, in the hands of the

Sovereign, Queen Elizabeth II. The Queen appointed Macmillan Prime Minister after taking advice from Winston Churchill and Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 5th Marquess of Salisbury,

surprising some observers who expected that Rab Butler would be chosen.

The political situation after Suez was so desperate that on taking office on 10 January he told Queen Elizabeth II he could not guarantee his government would last "six weeks". Macmillan

populated his government with many who had studied at the same school

as he: he filled government posts with 35 former Etonians, 7 of whom

sat in Cabinet. He was also devoted to family members: when Andrew Cavendish, 11th Duke of Devonshire was

later appointed (Minister for Colonial Affairs from 1963 to 1964

amongst other positions) he described his uncle's behaviour as "the

greatest act of nepotism ever". He was nicknamed Supermac in 1958 by cartoonist Victor 'Vicky' Weisz.

It was intended as mockery, but backfired, coming to be used in a

neutral or friendly fashion. Weisz tried to label him with other names,

including "Mac the Knife" at the time of widespread cabinet changes in

1962, but none of these caught on.

Macmillan brought the monetary concerns of the Exchequer into office; the economy was his prime concern. His One Nation approach to the economy was to seek high or full employment. This contrasted with his mainly monetarist Treasury

ministers who argued that the support of sterling required strict

controls on money and hence an unavoidable rise in unemployment. Their

advice was rejected and in January 1958 the three Treasury ministers Peter Thorneycroft, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Nigel Birch, Economic Secretary to the Treasury, and Enoch Powell, the Financial Secretary to the Treasury, resigned. Macmillan, away on a tour of the Commonwealth, brushed aside this incident as 'a little local difficulty'. Macmillan took close control of foreign policy. He worked to narrow the post-Suez rift with the United States, where his wartime friendship with Dwight D. Eisenhower was key; the two had a productive conference in Bermuda as early as March 1957. In February 1959 Macmillan became the first Western leader to visit the Soviet Union since the Second World War. Talks with Nikita Khrushchev eased tensions in East-West relations over West Berlin and led to an agreement in principle to stop nuclear tests and to hold a further summit meeting of Allied and Soviet heads of government. In the Middle East, faced by the 1958 collapse of the Baghdad Pact and the spread of Soviet influence, Macmillan acted decisively to restore the confidence of Gulf allies, using the RAF and special forces to defeat a revolt backed by Saudi Arabia and Egypt against the Sultan of Oman in July 1957, deploying airborne battalions to defend Jordan against Syrian subversion in July 1958, and deterring a threatened Iraqi invasion of Kuwait by landing a brigade group in July 1960. Macmillan was also a major proponent and architect of decolonisation. The Gold Coast was granted independence as Ghana, and the Federation of Malaya achieved independence within the Commonwealth of Nations in 1957. In

April 1957 Macmillan reaffirmed his strong support for the British

nuclear deterrent. A succession of prime ministers since the Second World War had been determined to persuade the United States to revive wartime co-operation in

the area of nuclear weapons research. Macmillan believed that one way

to encourage such co-operation would be for the United Kingdom to speed

up the development of its own hydrogen bomb, which was successfully tested on 8 November 1957. Macmillan's decision led to increased demands on the Windscale and (subsequently) Calder Hall nuclear plants to produce plutonium for military purposes. As a result the safety margins of the radioactive materials inside the Windscale reactor were eroded. This contributed to the Windscale accident on

the night of 10 October 1957, in which a fire broke out in the

plutonium plant of Pile No. 1, and nuclear contaminants travelled up a

chimney where the filters blocked some but not all of the contaminated

material. The radioactive cloud spread to south-east England and

fallout reached mainland Europe. Although scientists had warned of the

dangers of such an accident for some time, the government blamed the

workers who had put out the fire for 'an error of judgement', rather

than the political pressure for fast-tracking the megaton bomb. Macmillan,

concerned that public confidence in the nuclear programme might be

shaken and that technical information might be misused by opponents of

defence co-operation in the US Congress, withheld all but the summary of a report into the Windscale fire prepared for the Atomic Energy Authority by Sir William Penney, director of the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment. While subsequently released files show that 'Macmillan's cuts were few and covered up few technical details', and that even the full report at the time found no danger to public health, later official estimates acknowledged the release of polonium-210 may have led directly to 25 to 50 deaths, and anti-nuclear groups linked it to 1,000 fatal cancers. On 25 March 1957 Macmillan also acceded to Eisenhower's request to base 60 Thor IRBMs in England under joint control, to replace the nuclear bombers of the Strategic Air Command,

which had been stationed under joint control in the country since 1948,

and were approaching obsolescence. Partly as a consequence of this

favour, in late October 1957, the US McMahon Act was

eased to facilitate nuclear co-operation between the two governments,

initially with a view to producing cleaner weapons and reducing the

need for duplicate testing. The Mutual Defence Agreement followed on 3 July 1958, speeding up British ballistic missile development, notwithstanding unease expressed at the time about the impetus co-operation might give to atomic proliferation by arousing the jealousy of France and other allies. Macmillan led the Conservatives to victory in the October 1959 general election,

increasing his party's majority from 67 to 107 seats. The successful

campaign was based on the economic improvements achieved; the slogan

"Life's Better Under the Conservatives" was matched by Macmillan's own

remark, "indeed let us be frank about it — most of our people have never had it so good.",

usually paraphrased as "You've never had it so good". Such rhetoric

reflected a new reality of working class affluence; it has been argued:

"The key factor in the Conservative victory was that average real pay

for industrial workers had risen since Churchill’s 1951 victory by over

20 per cent". Critics contended that the actual economic growth rate was weak and distorted by increased defence spending. Britain's balance of payments problems

led to the imposition of a wage freeze in 1961 and, amongst other

factors, this caused the government to lose popularity and a series of by-elections in March 1962. Fearing for his own position, Macmillan organised a major Cabinet change in July 1962 — also named 'the night of long knives' as

a symbol of his alleged betrayal of the Conservative party. Eight

junior Ministers were sacked at the same time. The Cabinet changes were

widely seen as a sign of panic, and the young Liberal MP Jeremy Thorpe said

of Macmillan's dismissal of so many of his colleagues, 'greater love

hath no man than this, than to lay down his friends for his life'. Macmillan supported the creation of the National Incomes Commission as

a means to institute controls on income as part of his

growth without inflation policy. A further series of subtle indicators

and controls were also introduced during his premiership. The special relationship with the United States continued after the election of President John F. Kennedy, whose sister had married a nephew of Macmillan's wife. The Prime Minister was supportive throughout the Cuban missile crisis of 1962 and Kennedy consulted him by telephone every day. The British Ambassador David Ormsby-Gore was a close family friend of the President and actively involved in White House discussions on how to resolve the crisis. Macmillan's first government had seen the first phase of the sub-Saharan African independence movement, which accelerated under his second government. His celebrated 'wind of change' speech in Cape Town on his African tour in February 1960 is considered a landmark in the process of decolonisation. Nigeria, the Southern Cameroons and British Somaliland were granted independence in 1960, Sierra Leone and Tanganyika in 1961, Uganda in 1962, and Kenya in 1963. Zanzibar merged with Tanganyika to form Tanzania in 1963. All remained within the Commonwealth but British Somaliland, which merged with Italian Somaliland to form Somalia. Macmillan's policy overrode the hostility of white minorities and the Conservative Monday Club. South Africa left the multiracial Commonwealth in 1961 and Macmillan acquiesced to the dissolution of the Central African Federation by the end of 1963. In Southeast Asia, Malaya and the then-crown colonies of Sabah (British North Borneo), Sarawak and Singapore became independent as Malaysia in 1963. The

speedy transfer of power maintained the goodwill of the new nations but

critics contended it was premature. In justification Macmillan quoted Lord Macaulay in 1851: Macmillan was also a force in the successful negotiations leading to the signing of the 1962 Partial Test Ban Treaty by

the United Kingdom, the United States and the Soviet Union. His

previous attempt to create an agreement at the May 1960 summit in Paris

had collapsed due to the U-2 Crisis of 1960.

Macmillan worked with states outside the European Economic Community (EEC) to form the European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which from 3 May 1960 established a free-trade area between the member

countries. Macmillan also saw the value of rapprochement with the EEC,

to which his government sought belated entry. In the event, Britain's

application to join was vetoed by French president Charles de Gaulle on

29 January 1963, in part due to de Gaulle's fear that 'the end would be

a colossal Atlantic Community dependent on America', and in part in

anger at the Anglo-American nuclear deal, from which France,

technologically lagging far behind, had been excluded.

The Profumo affair of

spring and summer 1963 permanently damaged the credibility of

Macmillan's government. He survived a Parliamentary vote with a

majority of 69, one less than had been thought necessary for his

survival, and was afterwards joined in the smoking-room only by his son

and son-in-law, not by any Cabinet minister. Nonetheless, Butler and

Maudling (who was very popular with backbench MPs at that time)

declined to push for his resignation, especially after a tide of

support from Conservative activists around the country. The

Profumo affair may have exacerbated Macmillan's ill-health. He was

taken ill on the eve of the Conservative Party conference, diagnosed

incorrectly with inoperable prostate cancer. Consequently, he resigned

on 18 October 1963. He felt privately that he was being hounded from

office by a backbench minority: Macmillan initially refused a peerage and retired from politics in September 1964. Macmillan had been elected Chancellor of the University of Oxford in 1960, in a campaign masterminded by Hugh Trevor-Roper,

and continued in this distinguished office for life, frequently

presiding over college events, making speeches and tirelessly raising

funds. According to Sir Patrick Neill QC,

the vice-chancellor, Macmillan 'would talk late into the night with

eager groups of students who were often startled by the radical views

he put forward, well into his last decade.' In retirement Macmillan also took up the chairmanship of his family's publishing house, Macmillan Publishers, from 1964 to 1974. He brought out a six-volume autobiography: The read was described by Macmillan's political enemy Enoch Powell as inducing 'a sensation akin to that of chewing on cardboard'. His wartime diaries were better received. Macmillan made occasional political interventions in retirement. Responding to a remark made by Labour Prime Minister Harold Wilson about not having boots in which to go to school, Macmillan retorted: 'If Mr

Wilson did not have boots to go to school that is because he was too

big for them.' Macmillan accepted the distinction of the Order of Merit from

the Queen in 1976. In October of that year he called for 'a Government

of National Unity', including all parties, that could command the

public support to resolve the economic crisis. Asked who could lead

such a coalition, he replied: 'Mr Gladstone formed his last Government when he was eighty-three. I'm only eighty-two. You mustn't put temptation in my way.' His plea was interpreted by party leaders as a bid for power and rejected. Macmillan still travelled widely, visiting China in October 1979, where he held talks with its leader, senior Vice-Premier Deng Xiaoping. Macmillan found himself drawn more actively into politics after Margaret Thatcher became Conservative leader and Prime Minister, and the record of his own premiership came under attack from the monetarists in the party, whose theories Thatcher supported. In a celebrated speech he wondered aloud where such theories had come from: On Macmillan's advice in April 1982 Thatcher excluded the Treasury from her Falklands War Cabinet.

She later said: 'I never regretted following Harold Macmillan's advice.

We were never tempted to compromise the security of our forces for

financial reasons. Everything we did was governed by military

necessity.' Macmillan finally accepted a peerage in 1984 and was created Earl of Stockton and Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden. He took the title from his former parliamentary seat on the border of the Durham coalfields, and in his maiden speech in the House of Lords he criticised Thatcher's handling of the coal miners' strike and her characterisation of Marxist militants as 'the enemy within'. He received an unprecedented standing ovation for his oration which included the words: As

Chancellor of Oxford Lord Stockton also condemned the university's

refusal in February 1985 to award Thatcher an honorary degree. He noted

that the decision represented a break with tradition, and predicted

that the snub would rebound on the university. Stockton is widely supposed to have likened Thatcher's policy of privatisation to 'selling the family silver'. What he did say (at a dinner of the Tory Reform Group at the Royal Overseas League on

8 November 1985) was that the sale of assets was commonplace among

individuals or states when they encountered financial difficulties:

'First of all the Georgian silver goes. And then all that nice furniture that used to be in the salon. Then the Canalettos go.' Profitable parts of the steel industry and the railways had been privatised, along with British Telecom: 'They were like two Rembrandts still left.' Stockton's speech was much commented on and a few days later he made a speech in the House of Lords to clarify what he had meant: In the last month of his life, he mournfully observed: Thatcher,

on receiving the news, hailed him as 'a very remarkable man and a very

great patriot', and said that his dislike of 'selling the family

silver' had never come between them. He was 'unique in the affection of

the British people'. Tributes came from around the world. US President Ronald Reagan said:

'The American people share in the loss of a voice of wisdom and

humanity who, with eloquence and gentle wit, brought to the problems of

today the experience of a long life of public service.' Outlawed ANC president Oliver Tambo sent his condolences: 'AsSouth Africans we shall always remember him for his efforts to encourage the apartheid regime to bow to the winds of change that continue to blow in South Africa.' Commonwealth Secretary-General Sir Shridath Ramphal affirmed:

'His own leadership in providing from Britain a worthy response to

African national consciousness shaped the post-war era and made the

modern Commonwealth possible.' A private funeral was held on 5 January 1987 at St Giles Church, Horsted Keynes, West Sussex, where Lord Stockton had regularly worshipped and read the lesson. Two hundred mourners attended, including 64 members of the Macmillan family, Thatcher and former premiers Lord Home of the Hirsel and Edward Heath, Lord Hailsham of St Marylebone, and 'scores of country neighbours'. The Prince of Wales sent a wreath 'in admiring memory'. Stockton was buried beside his wife, Lady Dorothy, and next to the graves of his parents and of his son, Maurice Macmillan. The House of Commons paid its tribute on 12 January 1987, with much reference made to the dead statesman's book, The Middle Way. Thatcher said: 'In his retirement Harold Macmillan occupied a unique place in the nation's affections', while Labour leader Neil Kinnock struck a more critical note: A public memorial service, attended by the Queen and thousands of mourners, was held on 10 February 1987 in Westminster Abbey. Stockton's

son Maurice had become heir to the earldom, but predeceased him

suddenly a month after his father's elevation. The 1st Earl was

succeeded instead by his grandson, Maurice's son, Alexander, Lord

Macmillan, who become the 2nd Earl of Stockton.

Macmillan attained real power and Cabinet rank

upon being sent to North Africa in 1942 as British government

representative to the Allies in the Mediterranean, reporting directly

to Prime Minister Winston Churchill over the head of the Foreign Secretary, Anthony Eden. During this assignment Macmillan served as liaison and mediator between Churchill and US General Dwight D. Eisenhower in North Africa, building a rapport with the latter that would prove helpful in his later career.“ The governing principle of the Colonial Empire should

be the principle of partnership between the various elements composing

it. Out of partnership comes understanding and friendship. Within the

fabric of the Commonwealth lies the future of the Colonial territories. ”

Macmillan served as Chancellor of the Exchequer 1955 – 1957. In this office he insisted that Eden's de facto deputy Rab Butler not

be treated as senior to him, and threatened resignation until he was

allowed to cut bread and milk subsidies. One of Macmillan's innovations at the Treasury was the introduction of premium bonds, announced in his budget of 17 April 1956. Although the Labour Opposition initially decried the sale as a 'squalid raffle', it proved an immediate hit with the public. During the Suez Crisis, according to Shadow Chancellor Harold Wilson,

Macmillan was 'first in, first out': first very supportive of the

invasion, then a prime mover in Britain's withdrawal in the wake of the

financial crisis.“ Nothing

he can say can do very much good and almost anything he may say may do

a great deal of harm. Anything he says that is not obvious is

dangerous; whatever is not trite is risky. He is forever poised between

the cliché and the indiscretion. ”

Macmillan cancelled the Blue Streak ballistic missile system in April 1960 over concerns about its vulnerability to a pre-emptive attack. Instead he opted to replace the existing Blue Steel stand-off bomb with the Skybolt missile system, to be developed jointly with the United States. From the same year Macmillan also permitted the US Navy to station Polaris submarines at Holy Loch, Scotland, as a replacement for Thor. When Skybolt was in turn unilaterally cancelled by US Defence Secretary Robert McNamara, Macmillan negotiated with US President John F. Kennedy the purchase of Polaris missiles from the United States under the Nassau agreement in December 1962.

“ Many

politicians of our time are in the habit of laying it down as a

self-evident proposition that no people ought to be free until they are

fit to use their freedom. The maxim is worthy of the fool in the old

story, who resolved not to go into the water till he had learnt to

swim. If men are to wait for liberty till they become wise and good in

slavery, they may indeed wait for ever. ”

Macmillan was succeeded as Prime Minister by the Foreign Secretary Alec Douglas-Home in

a controversial move; it was alleged that Macmillan had pulled strings

and utilised the party's grandees, nicknamed 'The Magic Circle', to

ensure that Butler was not chosen as his successor.“ Some

few will be content with the success they have had in the assassination

of their leader and will not care very much who the successor is ...

They are a band that in the end does not amount to more than 15 or 20

at the most. ”

“ Was it America? Or was it Tibet? It is quite true, many of Your Lordships will remember it operating in the nursery. How do you treat a cold? One nanny said, 'Feed a cold'; she was a neo-Keynesian. The other said, 'Starve a cold'; she was a monetarist. ” “ It

breaks my heart to see — and I cannot interfere — what is happening in our

country today. This terrible strike, by the best men in the world, who

beat the Kaiser's and Hitler's

armies and never gave in. It is pointless and we cannot afford that

kind of thing. Then there is the growing division of Conservative

prosperity in the south and the ailing north and Midlands. We used to have battles and rows but they were quarrels. Now there is a

new kind of wicked hatred that has been brought in by different types

of people. ” “ When

I ventured the other day to criticise the system I was, I am afraid,

misunderstood. As a Conservative, I am naturally in favour of returning

into private ownership and private management all those means of production and

distribution which are now controlled by state capitalism. I am sure

they will be more efficient. What I ventured to question was the using

of these huge sums as if they were income. ”

Harold Macmillan, 1st Earl of Stockton, died on 29 December 1986, at Birch Grove, the Macmillan family mansion on the edge of Ashdown Forest near Chelwood Gate in East Sussex. He was aged 92 years and 322 days — the greatest age attained by a British Prime Minister until surpassed by James Callaghan on 14 February 2005. His grandson and heir Alexander, Viscount Macmillan of Ovenden, said: 'In the last 48 hours he was very weak but entirely reasonable

and intelligent. His last words were, "I think I will go to sleep now".'“ Sixty-three

years ago ... the unemployment figure (in Stockton-on-Tees) was then

29%. Last November ... the unemployment (there) is 28%. A rather sad

end to one's life. ” “ Death

and distance cannot lend sufficient enchantment to alter the view that

the period over which he presided in the 1950s, whilst certainly and

thankfully a period of rising affluence and confidence, was also a time

of opportunities missed, of changes avoided. Harold Macmillan was, of

course, not solely or even pre-eminently responsible for that. But we

cannot but record with frustration the fact that the vigorous and

perceptive attacker of the status quo in the 1930s became its emblem

for a time in the late 1950s before returning to be its critic in the

1980s. ”