<Back to Index>

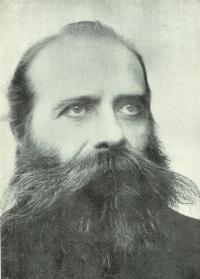

- Philosopher Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann, 1842

- Painter and Sculptor George Frederic Watts, 1817

- Prime Minister of Australia William "Billy" McMahon, 1908

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Robert Eduard von Hartmann (February 23, 1842 – June 5, 1906), was a German philosopher.

He was born in Berlin, and educated with the intention of a military career. He entered the artillery of the Guards as an officer in 1860, but was forced to leave in 1865 because of a knee problem. After some hesitation between music and philosophy, he decided to make the latter his profession, and in 1867 obtained a Ph.D. from the University of Rostock. He subsequently returned to Berlin, and died at Grosslichterfelde.

His reputation as a philosopher was established by his first book, The Philosophy of the Unconscious (1869). This success was largely due to the originality of its title, the diversity of its contents (Von Hartmann professing to obtain his speculative results by the methods of inductive science, and making plentiful use of concrete illustrations), the fashionableness of its pessimism and the vigour and lucidity of its style. The conception of the Unconscious, by which Von Hartmann describes his ultimate metaphysical principle, is not at bottom as paradoxical as it sounds, being merely a new and mysterious designation for the Absolute of German metaphysicians.

The Unconscious appears as a combination of the metaphysics of Hegel with that of Arthur Schopenhauer. The Unconscious is both Will and Reason and the absolute all-embracing ground of all existence. Von Hartmann thus combines pantheism with panlogism in a manner adumbrated by Schelling in his positive philosophy. Nevertheless Will and not Reason is the primary aspect of the Unconscious, whose melancholy career is determined by the primacy of the Will and the subservience of the Reason. Precosmically the Will is potential and the Reason latent, and the Will is void of reason when it passes from potentiality to actual willing. This latter is absolute misery, and to cure it the Unconscious evokes its Reason and with its aid creates the best of all possible worlds, which contains the promise of its redemption from actual existence by the emancipation of the Reason from its subjugation to the Will in the conscious reason of the enlightened pessimist. When the greater part of the Will in existence is so far enlightened by reason as to perceive the inevitable misery of existence, a collective effort to will non-existence will be made, and the world will relapse into nothingness, the Unconscious into quiescence.

Von Hartmann is a pessimist, but not an unmitigated one. The individual's happiness is indeed unattainable either here and now or hereafter and in the future, but he does not despair of ultimately releasing the Unconscious from its sufferings. He differs from Schopenhauer in making salvation by the negation of the Will-to-live depend on a collective social effort and not on individualistic asceticism. The conception of a redemption of the Unconscious also supplies the ultimate basis of Von Hartmann's ethics. We must provisionally affirm life and devote ourselves to social evolution, instead of striving after a happiness which is impossible; in so doing we shall find that morality renders life less unhappy than it would otherwise be. Suicide, and all other forms of selfishness, are highly reprehensible. Epistemologically Von Hartmann is a transcendental realist, who ably defends his views and acutely criticizes those of his opponents. His realism enables him to maintain the reality of Time, and so of the process of the world's redemption.