<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106 B.C.

- Painter August Macke, 1887

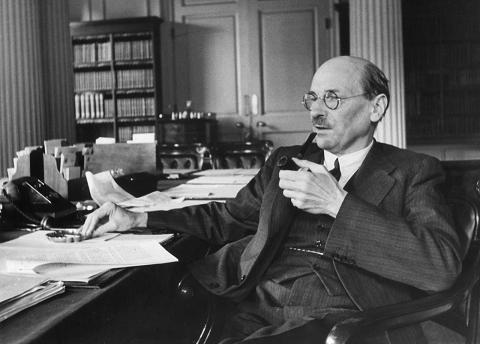

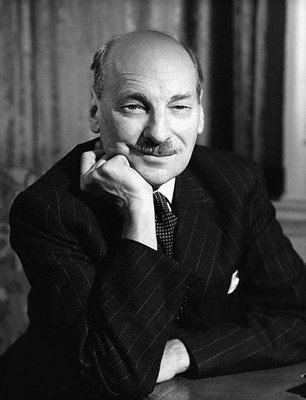

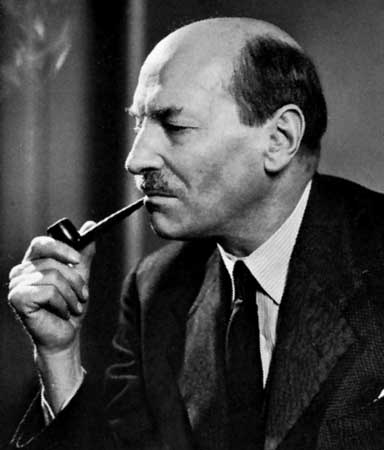

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Clement Richard Attlee, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Clement Richard Attlee, 1st Earl Attlee, KG, OM, CH, PC, FRS (3 January 1883 – 8 October 1967) was a British Labour politician who served as the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1945 to 1951, and as the Leader of the Labour Party from 1935 to 1955. He was also the first person to hold the office of Deputy Prime Minister, under Winston Churchill in the wartime coalition government, before leading the Labour Party to a landslide election victory over Churchill's Conservative Party in 1945. He was the first Labour Prime Minister to serve a full Parliamentary term, and the first to command a Labour majority in Parliament.

The government he led put in place the post-war settlement, based upon the assumption that full employment would be maintained by Keynesian policies, and that a greatly enlarged system of social services would be created – aspirations that had been outlined in the wartime Beveridge Report. Within this context, his government undertook the nationalisation of major industries and public utilities as well as the creation of the National Health Service. After initial Conservative opposition to Keynesian fiscal policy, this settlement was broadly accepted by all parties until Margaret Thatcher became Prime Minister in 1979 and neoliberalism became mainstream. His government also presided over the decolonisation of a large part of the British Empire when India, Pakistan, Burma, Sri Lanka and Jordan obtained their independence. The British Mandate of Palestine also came to an end with the creation of Israel on the day of British withdrawal. In 2004, he was voted the greatest British prime minister of the 20th century in a poll of 139 professors organised by MORI.

Attlee was born in Putney,

London, the seventh of eight children. His father was Henry Attlee

(1841 – 1908), a solicitor, and his mother was Ellen Bravery Watson

(1847 – 1920). Attlee was educated at Northaw School, a boys' preparatory school near Pluckley in Kent (which in 1952 was relocated and named Norman Court School), followed by Haileybury College, a famous boarding school in Hertford Heath near Hertford in Hertfordshire, followed by University College at the University of Oxford, where he graduated with a Second Class Honours BA in Modern History in 1904. Attlee then trained as a lawyer, and was called to the Bar in 1906. From 1906 to 1909, Attlee worked as manager of Haileybury House, a charitable club for working-class boys in Limehouse in the East End of London run by his old school. Prior to this, his political views had been conservative. However, he was shocked by the poverty and deprivation he saw while working with slum children. He came to the view that private charity would never be sufficient to alleviate poverty, and only massive action and income redistribution by the state would have any serious effect. This caused him to convert to socialism. He joined the Independent Labour Party in 1908, and became active in London local politics. In 1909 he worked briefly as secretary for Beatrice Webb, and from 1909 to 1910 he worked as secretary for Toynbee Hall. In 1911 he took up a government job as an 'official explainer', touring the country to explain David Lloyd George's National Insurance Act. He spent the summer of that year touring Essex and Somerset on a bicycle, explaining the Act at public meetings. Attlee became a lecturer at the London School of Economics in 1912, but promptly applied for a Commission in August 1914 for World War I. During World War I, Attlee was given the rank of captain and served with the South Lancashire Regiment in the Gallipoli Campaign in Turkey. After a period of fighting in the heat, sand and flies he became ill with dysentery and was sent to hospital in Malta to recover. This may have saved his life, as while he was in hospital he missed the Battle of Sari Bair in which many of his comrades were killed. Attlee

had gained a reputation among his superiors as a competent leader. When

he returned to the front, he was informed that his company had been

chosen to hold the final lines when Gallipoli was evacuated. He was the

last-but-one man to be evacuated from Suvla Bay (the last being General F.S. Maude). The Gallipoli Campaign had been masterminded by Winston Churchill.

Attlee believed that it was a bold strategy, which could have been

successful if it had been better implemented. This gave him an

admiration for Churchill as a military strategist, which improved their

working relationship in later years. He later served in the Mesopotamian Campaign in Iraq, where he was badly wounded at El Hannah after being hit in the leg by shrapnel from

an exploding shell while taking enemy trenches. He was sent back to

England to recover, and spent most of 1917 training soldiers. He was

sent to France in June 1918 to serve on the Western Front for the last months of the war. In 1917 he had been promoted to the rank of Major, and continued to be known as "Major Attlee" for much of the inter-war period. His decision to fight in the war caused a rift between him and his older brother Tom Attlee, who as a pacifist and a conscientious objector spent much of the war in prison. After the war, he returned to teaching at the London School of Economics until 1923. Attlee met Violet Millar on a trip to Italy in 1921. Within a few weeks of their return they became engaged and were married at Christ Church, Hampstead, on 10 January 1922. Theirs

would be a devoted marriage until her death in 1964. Their four

children were Lady Janet Helen (b. 1923), Lady Felicity Ann (1925 – 2007), Martin Richard (1927 – 91) and Lady Alison Elizabeth (b. 1930). Attlee returned to local politics in the immediate post-war period, becoming mayor of the Metropolitan Borough of Stepney in 1919, one of London's poorest inner-city boroughs. During his time as mayor, the council undertook action to tackle slum landlords who

charged high rents but refused to spend money on keeping their property

in habitable condition. The council served and enforced legal orders on

house-owners to repair their property. It also appointed health

visitors and sanitary inspectors, and reduced the infant mortality rate. In 1920, while mayor, he wrote his first book, "The Social Worker",

which set out many of the principles which informed his political

philosophy and were to underpin the actions of his government in latter

years. The book attacked the idea that looking after the poor could be left to voluntary action. He wrote: 'Charity

is a cold grey loveless thing. If a rich man wants to help the poor, he

should pay his taxes gladly, not dole out money at a whim'. He went on to write: 'In

a civilised community, although it may be composed of self-reliant

individuals, there will be some persons who will be unable at some

period of their lives to look after themselves, and the question of

what is to happen to them may be solved in three ways - they may be

neglected, they may be cared for by the organised community as of

right, or they may be left to the goodwill of individuals in the

community. The first way is intolerable, and as for the third: Charity

is only possible without loss of dignity between equals. A right

established by law, such as that to an old age pension, is less galling

than an allowance made by a rich man to a poor one, dependent on his

view of the recipient’s character, and terminable at his caprice'. He strongly supported the Poplar Rates Rebellion led by George Lansbury in 1921. This put him into conflict with many of the leaders of the London Labour Party, including Herbert Morrison. At the 1922 general election, Attlee became the Member of Parliament (MP) for the constituency of Limehouse in Stepney. He helped Ramsay MacDonald, whom at the time he admired, get elected as Labour Party leader at the 1922 Labour leadership election, a decision which he later regretted. He served as Ramsay MacDonald's parliamentary private secretary for

the brief 1922 parliament. His first taste of ministerial office came

in 1924, when he served as Under-Secretary of State for War in the

short-lived first Labour government, led by MacDonald. Attlee opposed the 1926 General Strike,

believing that strike action should not be used as a political weapon.

However, when it happened he did not attempt to undermine it. At the

time of the strike he was chairman of the Stepney Borough Electricity

Committee. He negotiated a deal with the Electrical Trade Union that

they would continue to supply power to hospitals, but would end

supplies to factories. One firm, Scammell and Nephew Ltd, took a civil

action against Attlee and the other Labour members of the committee

(although not against the Conservative members who had also supported

this). The court found against Attlee and his fellow councillors and

they were ordered to pay £300 damages. The decision was later

reversed on appeal, but the financial problems caused by the episode

almost forced Attlee out of politics. In 1927 he was appointed a member of the multi-party Simon Commission, a Royal Commission set up to examine the possibility of granting self-rule to India.

As a result of the time he needed to devote to the commission, and

contrary to a promise made to Attlee by MacDonald to induce him to

serve on the commission, he was not initially offered a ministerial

post in the Second Labour Government. However,

his unsought service on the Commission was to equip Attlee (who was

later to have to decide the future of India as Prime Minister) with a

thorough exposure to India and many of its political leaders. In 1930, Labour MP Oswald Mosley left the party after its rejection of his proposals for solving the unemployment problem. Attlee was given Mosley's post of Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. He was Postmaster-General at the time of the 1931 crisis,

during which most of the party's leaders lost their seats. During the

course of the second Labour government, Attlee had become increasingly

disillusioned by Ramsay MacDonald, whom he came to regard as vain and incompetent, and later wrote scathingly of him in his autobiography. After the downfall of the second Labour government, the 1931 General Election was

held. The election was a disaster for the Labour Party, which lost over

200 seats; most of the party's senior figures lost their seats,

including Arthur Henderson the party leader. George Lansbury and

Attlee were among the few surviving Labour MPs who had served in

government. Accordingly, Lansbury became leader of the party and Attlee

became deputy leader. Attlee served as acting leader for nine months from December 1933, after Lansbury fractured his thigh in an accident. This

raised his public profile. During this period, financial problems again

almost forced Attlee to quit politics, as his wife was ill, and there

was then no separate salary for the Leader of the Opposition. He was persuaded to stay on, however, by Stafford Cripps, a wealthy socialist who agreed to pay him an additional salary. George

Lansbury, a convinced pacifist, resigned as leader at the 1935 Labour

Party conference, after the party voted in favour of sanctions against

Italy for its aggression against Abyssinia,

a policy which Lansbury strongly opposed. With a general election

looming, the Parliamentary Labour Party then appointed Attlee as interim leader, on the understanding that a leadership election would be held after the general election. Attlee led Labour through the 1935 general election, which saw the party stage a partial recovery from its disastrous performance in 1931, gaining over one hundred seats. In the post-election leadership contest held in November 1935, Attlee was opposed by Herbert Morrison and Arthur Greenwood.

Morrison was seen as the favourite by many, but was distrusted by many

sections of the party, especially the left. Arthur Greenwood's

leadership bid was hampered by his alcohol problem. Attlee came first in both the first and second ballots, and

subsequently retained the leadership, a post which he would retain

until 1955. Throughout the 1920s and most of the 1930s, the Labour Party's official policy, supported by Attlee, was to oppose rearmament, and support collective security under the League of Nations. However, with the rising threat from Nazi Germany,

and the ineffectiveness of the League of Nations, this policy lost

credibility. By 1937, Labour had jettisoned its pacifist position and

came to support rearmament and oppose Neville Chamberlain's policy of appeasement. In 1937 Attlee visited Spain and visited the British Battalion of the International Brigades fighting in the Spanish Civil War. One of the companies was named the 'Major Attlee Company' in his honour. Attlee remained opposition leader when war broke out in September 1939. The disastrous Norwegian campaign resulted in a motion of no confidence in the government. Although Chamberlain survived this, the reputation of his administration was so badly damaged that it was clear that a coalition government was necessary. The crisis coincided with the Labour Party Conference. Even if Attlee had been prepared to serve under Chamberlain (in

a "national emergency government"), he would not have been able to

carry the party with him. Consequently, Chamberlain tendered his

resignation, and Labour and the Liberals entered a coalition government

led by Winston Churchill. In the World War II coalition government, three interconnected committees ran the war. Churchill chaired the War Cabinet and the Defence Committee.

Attlee was his regular deputy in these committees, and answered for the

government in parliament when Churchill was absent. Attlee chaired the

third body, the Lord President's Committee, which ran the civil side of the war. As Churchill was most concerned with executing the war, the arrangement suited both men. Only

he and Churchill remained in the war cabinet from the formation of the

Government of National Unity to the 1945 election. Attlee was Lord Privy Seal (1940–42), Deputy Prime Minister (1942–45), Dominions Secretary (1942–43), and Lord President of the Council (1943–45).

Attlee supported Churchill in his continuation of Britain's resistance

after the French capitulation in 1940, and proved a loyal ally to

Churchill throughout the conflict; when the war cabinet had voted on whether to surrender, Attlee (along with fellow Labour minister Arthur Greenwood) voted in favour of fighting, giving Churchill the majority he needed to continue the war. Following

the end of the war in Europe in May 1945, Attlee and Churchill wanted

the coalition government to last until Japan had been defeated. However, Herbert Morrison argued

that the party would not accept this, and the Labour National Executive

Committee agreed with him. Churchill responded by resigning as

coalition Prime Minister and decided to call an election at once. The war set in motion profound social changes within Britain, and led to a popular desire for social reform. This mood was epitomised in the Beveridge Report.

The report assumed that the maintenance of full employment would be the

aim of postwar governments, and that this would provide the basis for

the welfare state.

Immediately on its release, it sold hundreds of thousands of copies.

All major parties were committed to this aim, but perhaps Attlee and

Labour were seen by the electorate as the best candidates to follow it

through. Labour campaigned on the theme of "Let Us Face the Future"

and positioned themselves as the party best placed to rebuild Britain

after the war, while the Conservatives campaign centred around

Churchill. With the hero status of Churchill, few expected a Labour

victory. However Churchill made some errors during the campaign: His

suggestion during a radio broadcast, that a Labour government would

require "some form of gestapo" to implement their socialist policies, was widely seen as being in bad taste, and backfired. The

results of the election when they were announced on 26 July, came as a

surprise to almost everyone, including Attlee: Labour had been swept to

power on a landslide, winning just under 50% of the vote, to the

Conservatives' 36%. Labour won 393 seats, giving them a majority of 147. The story goes that when Attlee visited King George VI at Buckingham Palace to kiss hands,

the notoriously laconic Attlee and the notoriously tongue-tied George

VI stood for some minutes in silence, before Attlee finally volunteered

the remark "I've won the election." The King replied "I know. I heard

it on the Six O'Clock News."

Now Prime Minister, Attlee appointed Ernest Bevin as Foreign Secretary; Hugh Dalton was appointed Chancellor of the Exchequer (it had widely been expected to be the other way around). Stafford Cripps became President of the Board of Trade, while Herbert Morrison was given the post of Deputy Prime Minister and given overall control of Labour's nationalisation programme. Aneurin Bevan became Minister of Health, whilst Ellen Wilkinson, the only woman to serve in Attlee's government, became Minister of Education. In domestic policy, the party had clear aims. Attlee's first Health Secretary, Aneurin Bevan, fought against the general disapproval of the medical establishment in creating the British National Health Service.

Although there are often disputes about its organisation and funding,

British parties to this day must still voice their general support for

the NHS in order to remain electable. The government set about implementing William Beveridge's plans for the creation of a 'cradle to grave' welfare state, and set in place an entirely new system of social security. Among the most important pieces of legislation was the National Insurance Act 1946, in which people in work paid a flat rate of national insurance.

In return, they (and the wives of male contributors) were eligible for

flat-rate pensions, sickness benefit, unemployment benefit, and funeral

benefit. Various other pieces of legislation provided for child benefit and support for people with no other source of income.

Attlee's government also carried out their manifesto commitment for nationalisation of basic industries and public utillities. The Bank of England and civil aviation were nationalised in 1946. Coal mining, the railways, road haulage, canals and cable and wireless were nationalised in 1947, electricity and gas followed in 1948. The steel industry was finally nationalised in 1951. By 1951 about 20% of the British economy had been taken into public ownership. Other changes included the creation of a National Parks system, the introduction of the Town and Country Planning system, and the repeal of the Trades Disputes Act 1927. Nevertheless, the most significant problem remained the economy; the war effort had

left Britain nearly bankrupt. The war had cost Britain about a quarter

of its national wealth. Overseas investments had been wound up to pay

for the war. The transition to a peacetime economy, and the maintaining

of strategic military commitments abroad led to continuous and severe

problems with the balance of trade. This meant that strict rationing of

food and other essential goods were continued in the post war period,

to force a reduction in consumption in an effort to limit imports, boost exports and stabilise the Pound Sterling so that Britain could trade its way out of its crisis. The abrupt ending of the American Lend-Lease program in August 1945 almost caused a crisis. This was mitigated by the Anglo-American loan negotiated in December 1945 by John Maynard Keynes, which provided some respite. The conditions attached to the loan included making the pound fully convertible to the dollar. When this was introduced in July 1947, it led to a currency crisis and convertibility had to be suspended after just five weeks. Britain benefited from the American Marshall Aid program

from 1948, and the economic situation improved significantly. However

another balance of payments crisis in 1949 forced Chancellor of the

Exchequer Stafford Cripps into devaluation of the pound. Despite these problems, one of the main achievements of Attlee's government was the maintenance of near full employment.

The government maintained most of the wartime controls over the

economy, including control over the allocation of materials and

manpower, and unemployment rarely rose above 500,000, or 3% of the total workforce. In fact labour shortages proved

to be more of a problem. One area where the government was not quite as

successful was in housing, which was also the responsibility of Aneurin

Bevan. The government had a target to build 400,000 new houses a year

to replace those which had been destroyed in the war, but shortages of

materials and manpower meant that less than half this number were built.

1947 proved to be a particularly difficult year for the government; an exceptionally cold winter that year caused coal mines to freeze and cease production, creating widespread power cuts and food shortages. The crisis led to an unsuccessful plot by Hugh Dalton to replace Attlee as Prime Minister with Ernest Bevin. Later that year Stafford Cripps tried to persuade Attlee to stand aside for Bevin. However these plots petered out after Bevin refused to co-operate. Later

that year, Hugh Dalton resigned as Chancellor after inadvertently

leaking details of the budget to a journalist, he was replaced by

Cripps. Attlee's government faced constant hostility from Conservative supporting sections of society, including the Conservative supporting press. The Sunday Times journalist

James Margach, wrote of the Attlee years; "I have never known the Press

so consistently and irresponsibly political, slanted and prejudiced".

As early as 1946 the Attorney-General Sir Hartley Shawcross attacked

"the campaign of calumny and misrepresentation which the Tory Party and

the Tory stooge press has directed at the Labour government. Freedom of

the press does not mean freedom to tell lies". In 1946 the government

set up a Royal Commission on the press which eventually led to the setting up of the Press Council in 1953. Relations with the Royal Family were also strained. A letter from Queen Elizabeth (later the Queen Mother),

dated 17 May 1947, showed "her decided lack of enthusiasm for the

socialist government" and describes the British electorate as "poor

people, so many half-educated and bemused" for electing Attlee over

Winston Churchill, whom she saw as a war hero. That said, according to

Lord Wyatt, this was to be expected as the Queen Mother was "the most

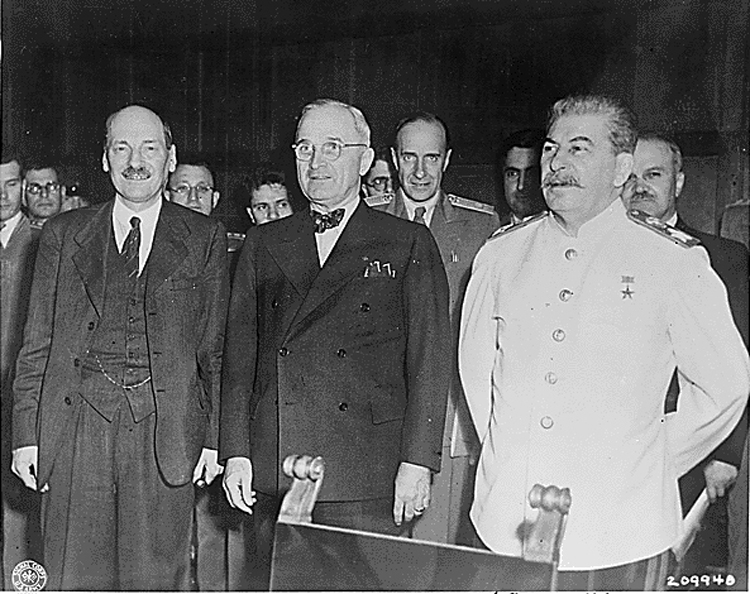

right-wing member of the Royal Family." In foreign affairs, Attlee's cabinet was concerned with four issues: postwar Europe, the onset of the cold war, the establishment of the United Nations, and decolonisation. The first two were closely related, and Attlee was assisted in these matters by Ernest Bevin. Attlee attended the later stages of the Potsdam Conference in the company of Truman and Stalin. In

the immediate aftermath of the war, the Government faced the challenge

of managing relations with Britain's former war-time ally, Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union. Attlee's Foreign Secretary, the former trade union leader Ernest Bevin, was passionately anti-communist, based largely on his experience of fighting communist influence in the

trades union movement. Bevin's initial approach to the USSR as Foreign

Secretary has been described by historian Kenneth O. Morgan as "wary

and suspicious, but not automatically hostile". In

an early "good-will" gesture that has been criticised more recently,

the Attlee government allowed the Soviets access, under the terms of a

1946 UK-USSR Trade Agreement, to several Rolls-Royce Nene jet engines. The Soviets, who at the time were well behind the West in jet technology, reverse-engineered the Nene, and installed their own version in the MiG-15 interceptor, used to good effect against US-UK forces in the subsequent Korean War, as well as in several later MiG models. After Stalin took political control of most of Eastern Europe and

began to subvert other governments in the Balkans, Attlee's and Bevin's

worst fears of Soviet intentions were borne out. The Attlee government

then became instrumental in the creation of the successful NATO defence alliance to protect Western Europe against any Soviet aggression. In

a crucial contribution to the economic stability of post-War Europe, Attlee's cabinet was instrumental in promoting the American Marshall Plan for the economic recovery of Europe. A group of left wing Labour MPs organised under the banner of "Keep Left",

urged the government to steer a middle way between the two emerging

superpowers, and advocated the creation of 'third force' of European

powers to stand between the USA and USSR. However, deteriorating

relations between Britain and the USSR, and Britain's economic reliance

on America, steered policy towards supporting America. Fear

of Soviet and American intentions led, in January 1947, to a secret

meeting of senior cabinet ministers, where it was decided to press

ahead with the development of Britain's independent nuclear deterrent,

an issue which later caused a split in the Labour Party, although the

first successful test did not occur until 1952, after Attlee had left

office.

In

1950 American president Harry S. Truman said that atomic weapons may be

used in the Korean War. Attlee became concerned with the power America

possessed and therefore called a meeting of some foreign affairs

ministers in order to discuss the issue that had evolved. Attlee's government was responsible for the first significant decolonisation of part of the British Empire -- India. Attlee appointed Lord Louis Mountbatten Viceroy

of India, and agreed to Mountbatten's request for plenipotentiary

powers for negotiating Indian independence. In view of implacable

demands by the political leadership of the Islamic community in British

India for a Muslim homeland, Mountbatten conceded the partition of India between a Hindu-majority India and a predominantly Muslim Pakistan (which at the time incorporated East Pakistan, now Bangladesh).

Partition was accomplished at the cost of large-scale population

movements and heavy communal bloodshed on both sides. The independence

of Burma and Ceylon was also negotiated around this time. Some of the new countries became British Dominions, the genesis of the modern Commonwealth of Nations. One of the most urgent problems concerned the future of the Palestine Mandate. British policies there were perceived by the Zionist movement and the Truman administration as pro-Arab and anti-Jewish, and in the

face of armed revolt of Jewish militant groups and increasing violence

of the local Arab population Britain had found itself unable to control

events. This was a very unpopular commitment and the evacuation of British troops and subsequent handing over of the issue to the UN was widely supported by the public.

The government's policies with regard to the other colonies, however,

particularly those in Africa, were very different. A major military base was built in Kenya,

and the African colonies came under an unprecedented degree of direct

control from London, as development schemes were implemented with a

view to helping solve Britain's desperate post-war balance of payments crisis, and raising African living standards. This 'new colonialism' was, however, generally a failure: in some cases, such as a then-infamous Tanganyika groundnut scheme, spectacularly so. The Labour Party was returned to power in the general election of 1950 with a much reduced parliamentary majority under the first-past-the-post voting system,

despite an increase in the popular vote. It was at this time that a

degree of Conservative opposition recovered at the expense of the

declining Liberal Party. By

1951, the Attlee government was looking increasingly exhausted, with

several of its most important ministers having died or ailing. The party split in 1951 over the austerity budget brought in by Hugh Gaitskell to pay for the cost of Britain's participation in the Korean War: Aneurin Bevan,

architect of the National Health Service (NHS), resigned to protest

against the new charges for "teeth and spectacles" introduced by the

budget, and was joined in this action by the later prime minister, Harold Wilson. Labour lost the general election of 1951 to

Churchill's renewed Conservatives, despite polling more votes than in

the 1945 election and more votes nationwide than the Conservative

party, and, indeed, the most votes Labour had ever won. His short list of Resignation Honours announced in November 1951 included an Earldom for William Jowitt, Lord Chancellor. Following

the defeat in 1951, Attlee continued to lead the party in opposition.

His last four years as leader are widely seen as one of the Labour

Party's weaker periods. The party became split between its right wing led by Hugh Gaitskell and its left led by Aneurin Bevan. One of his main reasons for staying on as leader was to frustrate the leadership ambitions of Herbert Morrison, whom

Attlee disliked for political and personal reasons. Attlee had

reportedly at one time favoured Bevan to succeed him as leader, but this became problematic after the latter split the party. Attlee, now aged 72, contested the 1955 general election against Anthony Eden,

which saw the Conservative majority increase. He stood down as Leader

of the Opposition in November 1955, and retired as leader of the Labour

party on 14 December 1955, having led the party for over twenty years,

and was succeeded by Hugh Gaitskell. He retired from the Commons and was elevated to the peerage to take his seat in the House of Lords as Earl Attlee and

Viscount Prestwood on 16 December 1955. In 1958 he was, along with

Bertrand Russell, one of a group of notables to establish the Homosexual Law Reform Society,

which campaigned for the decriminalisation of homosexual acts in

private by consenting adults, a reform which was voted through

parliament nine years later. He

attended Churchill's funeral in January 1965 - elderly and frail by

then, he had to remain seated in the freezing cold as the coffin was

carried, having tired himself out by standing at the rehearsal the

previous day. He lived to see Labour return to power under Harold Wilson in 1964, but also to see his old constituency of Walthamstow West fall to the Conservatives in a by-election in September 1967. Clement Attlee died of pneumonia at the age of 84 at Westminster Hospital on 8 October 1967. On his death, the title passed to his son Martin Richard Attlee, 2nd Earl Attlee (1927–91). It is now held by Clement Attlee's grandson John Richard Attlee, 3rd Earl Attlee. The third earl (a member of the Conservative Party) retained his seat in the Lords as one of the hereditary peers to remain under an amendment to Labour's 1999 House of Lords Act. When

Attlee died, his estate was sworn for probate purposes at a value of

£7,295, a relatively modest sum for so prominent a figure. His ashes are buried in the nave of Westminster Abbey, close to those of Lord Passfield and Ernest Bevin.