<Back to Index>

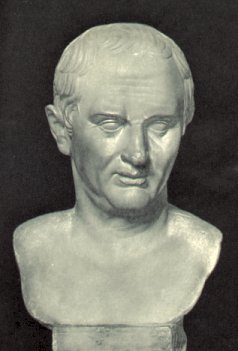

- Philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero, 106 B.C.

- Painter August Macke, 1887

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom Clement Richard Attlee, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Marcus Tullius Cicero (January 3, 106 BC – December 7, 43 BC) was a Roman philosopher, statesman, lawyer, political theorist, and Roman constitutionalist. He came from a wealthy municipal family of the equestrian order, and is widely considered one of Rome's greatest orators and prose stylists.

He introduced the Romans to the chief schools of Greek philosophy and created a Latin philosophical vocabulary (with neologisms such as humanitas, qualitas, quantitas, and essentia) distinguishing himself as a linguist,

translator, and philosopher. An impressive orator and successful

lawyer, Cicero thought that his political career was his most important

achievement. Today, he is appreciated primarily for his humanism and

philosophical and political writings. His voluminous correspondence,

much of it addressed to his friend Atticus, has been especially influential, introducing the art of refined letter writing to European culture. Cornelius Nepos,

the 1st century BC biographer of Atticus, remarked that Cicero's

letters contained such a wealth of detail "concerning the inclinations

of leading men, the faults of the generals, and the revolutions in the

government" that their reader had little need for a history of the

period. Cicero's speeches and letters remain some of the most important primary sources that survive on the last days of the Roman Republic. During the chaotic latter half of the first century B.C. marked by civil wars and the dictatorship of Gaius Julius Caesar, Cicero championed a return to the traditional republican government.

However, his career as a statesman was marked by inconsistencies and a

tendency to shift his position in response to changes in the political

climate. His indecision may be attributed to his sensitive and

impressionable personality; he was prone to overreaction in the face of

political and private change. "Would that he had been able to endure

prosperity with greater self-control and adversity with more

fortitude!" wrote C. Asinius Pollio, a contemporary Roman statesman and historian. Cicero was born in 106 BC in Arpinum, a hill town 100 kilometers (60 miles) south of Rome. His father was a well-to-do member of the equestrian order with

good connections in Rome. Though he was a semi-invalid who could not

enter public life, he compensated for this by studying extensively.

Although little is known about Cicero's mother, Helvia, it was common

for the wives of important Roman citizens to be responsible for the

management of the household. Cicero's brother Quintus wrote in a letter

that she was a thrifty housewife. Cicero's cognomen, or personal surname, comes from the Latin for chickpea, cicer. Plutarch explains

that the name was originally given to one of Cicero's ancestors who had

a cleft in the tip of his nose resembling a chickpea. However it is

more likely that Cicero's ancestors prospered through the cultivation

and sale of chickpeas. Romans often chose down-to-earth personal surnames: the famous family names of Fabius, Lentulus, and Piso come

from the Latin names of beans, lentils, and peas. Plutarch writes that

Cicero was urged to change this deprecatory name when he entered

politics, but refused, saying that he would make Cicero more glorious than Scaurus ("Swollen-ankled") and Catulus ("Puppy"). During

this period in Roman history, if one was to be considered "cultured",

it was necessary to be able to speak both Latin and Greek. The Roman

upper class often preferred Greek to Latin in private correspondence. Cicero,

like most of his contemporaries, was therefore educated in the

teachings of the ancient Greek philosophers, poets and historians. The

most prominent teachers of oratory of that time were themselves Greek. Cicero

used his knowledge of Greek to translate many of the theoretical

concepts of Greek philosophy into Latin, thus translating Greek

philosophical works for a larger audience. It was precisely his broad

education that tied him to the traditional Roman elite. According to Plutarch, Cicero was an extremely talented student, whose learning attracted attention from all over Rome, affording him the opportunity to study Roman law under Quintus Mucius Scaevola. Cicero's fellow students were Gaius Marius Minor, Servius Sulpicius Rufus (who became a famous lawyer, one of the few whom Cicero considered superior to himself in legal matters), and Titus Pomponius. The latter two became Cicero's friends for life, and Pomponius (who later received the cognomen "Atticus" for his philhellenism) would become Cicero's longtime chief emotional support and adviser. Cicero wanted to pursue a public civil service career along the steps of the Cursus honorum. In 90 BC – 88 BC, Cicero served both Gnaeus Pompeius Strabo and Lucius Cornelius Sulla as they campaigned in the Social War,

though he had no taste for military life, being an intellectual first

and foremost. Cicero started his career as a lawyer around 83-81 BC.

His first major case, of which a written record is still extant, was

his 80 BC defense of Sextus Roscius on the charge of parricide. Taking

this case was a courageous move for Cicero; parricide was considered an

appalling crime, and the people whom Cicero accused of the murder — the

most notorious being Chrysogonus — were favorites of Sulla. At this time it would have been easy for Sulla to

have the unknown Cicero murdered. Cicero's defense was an indirect

challenge to the dictator Sulla, and on the strength of his case,

Roscius was acquitted. In 79 BC, Cicero left for Greece, Asia Minor and Rhodes, perhaps because of the potential wrath of Sulla. Cicero traveled to Athens, where he again met Atticus,

who had become an honorary citizen of Athens and introduced Cicero to

some significant Athenians. In Athens, Cicero visited the sacred sites

of the philosophers, but not before he consulted different rhetoricians in order to learn a less exhaustive style of speech. His chief instructor was the rhetorician Apollonius Molon of Rhodes.

He instructed Cicero in a more expansive and less intense form of

oratory that would define Cicero's individual style in years to come. Cicero's

interest in philosophy figured heavily in his later career and led to

him introducing Greek philosophy to Roman culture, creating a

philosophical vocabulary in Latin. In 87 BC, Philo of Larissa, the head of the Academy that was founded by Plato in Athens about 300 years earlier, arrived in Rome. Cicero, "inspired by an extraordinary zeal for philosophy", sat

enthusiastically at his feet and absorbed Plato's philosophy, even

calling Plato his god. He admired especially Plato's moral and

political seriousness, but he also respected his breadth of

imagination. Cicero nonetheless rejected Plato's theory of Ideas. Cicero married Terentia probably

at the age of 27, in 79 BC. According to the upper class mores of the

day it was a marriage of convenience, but endured harmoniously for some

30 years. Terentia's family was wealthy, probably the plebeian noble

house of Terenti Varrones, thus meeting the needs of Cicero's political

ambitions in both economic and social terms. She had a uterine sister

(or perhaps first cousin) named Fabia, who as a child had become a Vestal Virgin –

a very great honour. Terentia was a strong-willed woman and (citing

Plutarch) "she took more interest in her husband's political career

than she allowed him to take in household affairs". In

the 40s BC, Cicero's letters to Terentia became shorter and colder. He

complained to his friends that Terentia had betrayed him but did not

specify in which sense. Perhaps the marriage simply could not outlast

the strain of the political upheaval in Rome, Cicero's involvement in

it, and various other disputes between the two. The divorce appears to

have taken place in 51 BC or shortly before. In 46 or 45 BC, Cicero married a young girl, Publilia, who had been his ward.

It is thought that Cicero needed her money, particularly after having

to repay the dowry of Terentia, who came from a wealthy family. This marriage did not last long. Although his marriage to Terentia was one of convenience, it is commonly known that Cicero held great love for his daughter Tullia. When she suddenly became ill in February 45 BC and died after having

seemingly recovered from giving birth to a son in January, Cicero was

stunned. "I have lost the one thing that bound me to life" he wrote to

Atticus. Atticus

told him to come for a visit during the first weeks of his bereavement,

so that he could comfort him when his pain was at its greatest. In

Atticus's large library, Cicero read everything that the Greek

philosophers had written about overcoming grief, "but my sorrow defeats

all consolation." Caesar and Brutus as well as Servius Sulpicius Rufus sent him letters of condolence. Cicero hoped that his son Marcus would become a philosopher like him, but Marcus himself wished for a military career. He joined the army of Pompey in 49 BC and after Pompey's defeat at Pharsalus 48 BC, he was pardoned by Caesar. Cicero sent him to Athens to study as a disciple of the peripatetic philosopher Kratippos in 48 BC, but he used this absence from "his father's vigilant eye" to "eat, drink and be merry." After Cicero's murder he joined the army of the Liberatores but was later pardoned by Augustus. Augustus' bad conscience for having put Cicero on the proscription list during the Second Triumvirate led him to aid considerably Marcus Minor's career. He became an augur, and was nominated consul in 30 BC together with Augustus, and later appointed proconsul of Syria and the province of Asia. His first office was as one of the twenty annual Quaestors,

a training post for serious public administration in a diversity of

areas, but with a traditional emphasis on administration and rigorous

accounting of public monies under the guidance of a senior magistrate

or provincial commander. Cicero served as quaestor in western Sicily in

75 BC and demonstrated honesty and integrity in his dealings with the

inhabitants. As a result, the grateful Sicilians asked Cicero to

prosecute Gaius Verres,

a governor of Sicily, who had badly plundered Sicily. His prosecution

of Gaius Verres was a great forensic success for Cicero. Upon the

conclusion of this case, Cicero came to be considered the greatest

orator in Rome. However, the view that Cicero may have taken the case

for other reasons is viable. Quintus Hortensius Hortalus was, at this point, known as the best lawyer in Rome;

to beat him would guarantee much success and prestige that Cicero

needed to start his career. Nevertheless, his oratory skill is shown

through his character assassination of Verres and various other

persuasive techniques used towards the jury. One such example is found

in Against Verres I, where he states 'with you on this bench,

gentlemen, with Marcus Acilius Glabrio as your president, I do not

understand what Verres can hope to achieve'. Oratory was considered a

great art in ancient Rome and an important tool for disseminating

knowledge and promoting oneself in elections, in part because there was

no regular media at the time. Despite his great success as an advocate,

Cicero lacked reputable ancestry: he was neither noble nor patrician. Cicero grew up in a time of civil unrest and war. Sulla’s victory in the first of many civil wars led to a new constitutional framework that undermined libertas (liberty), the fundamental value of the Roman Republic. Nonetheless, Sulla’s reforms strengthened the position of the equestrian class, contributing to that class’s growing political power. Cicero was both an Italian eques and a novus homo, but more importantly he was a Roman constitutionalist.

His social class and loyalty to the Republic ensured he would "command

the support and confidence of the people as well as the Italian middle

classes." The fact that the optimates faction

never truly accepted Cicero undermined his efforts to reform the

Republic while preserving the constitution. Nevertheless, he was able

to successfully ascend the Roman cursus honorum, holding each magistracy at or near the youngest possible age: quaestor in 75 (age 31), aedile in 69 (age 37), and praetor in 66 (age 40), where he served as president of the "Reclamation" (or extortion) Court. He was then elected consul at age 43.

Cicero was elected Consul for the year 63 BC. His co-consul for the year, Gaius Antonius Hybrida, played a minor role. During his year in office he thwarted a conspiracy centred on assassinating him and overthrowing the Roman Republic with the help of foreign armed forces, led by Lucius Sergius Catilina. Cicero procured a Senatus Consultum de Re Publica Defendenda (a declaration of martial law), and he drove Catiline from the city with four vehement speeches (the Catiline Orations),

which to this day remain outstanding examples of his rhetorical style.

The Orations listed Catiline and his followers' debaucheries, and

denounced Catiline's senatorial sympathizers as roguish and dissolute

debtors, clinging to Catiline as a final and desperate hope. Cicero

demanded that Catiline and his followers leave the city. At the

conclusion of his first speech, Catiline burst from the Temple of Jupiter Stator. In his following speeches Cicero did not directly address Catiline. He delivered the second and third orations before the people,

and the final before the Senate. By these speeches Cicero wanted to

prepare the Senate for the worst possible case; he also delivered more

evidence against Catiline. Catiline

fled and left behind his followers to start the revolution from within

while Catiline assaulted the city with an army of "moral bankrupts and

honest fanatics". Catiline had attempted to involve the Allobroges, a tribe of Transalpine Gaul,

in their plot, but Cicero, working with the Gauls, was able to seize

letters which incriminated the five conspirators and forced them to

confess their crimes in front of the Senate. The Senate then deliberated upon the conspirators' punishment. As it was the dominant advisory body to the various legislative assemblies rather than a judicial body,

there were limits to its power; however, martial law was in effect, and

it was feared that simple house arrest or exile — the standard options

— would not remove the threat to the state. At first most in the Senate

spoke for the "extreme penalty"; many were then swayed by Julius

Caesar, who decried the precedent it would set and argued in favor of

life imprisonment in various Italian towns. Cato then rose in defence of the death penalty and all the Senate finally agreed on the matter. Cicero had the conspirators taken to the Tullianum, the notorious Roman prison, where they were strangled. Cicero himself accompanied the former consul Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, one of the conspirators, to the Tullianum. Cicero received the honorific "Pater Patriae"

for his efforts to suppress the conspiracy, but lived thereafter in

fear of trial or exile for having put Roman citizens to death without

trial. In 60 BC Julius Caesar invited Cicero to be the fourth member of his existing partnership with Pompey and Marcus Licinius Crassus, an assembly that would eventually be called the First Triumvirate. Cicero refused the invitation because he suspected it would undermine the Republic. In 58 BC Publius Clodius Pulcher, the tribune of the plebs, introduced a law (the Leges Clodiae)

threatening exile to anyone who executed a Roman citizen without a

trial. Cicero, having executed members of the Catiline conspiracy four

years previously without formal trial, and having had a public

falling-out with Clodius, was clearly the intended target of the law.

Cicero argued that the senatus consultum ultimum indemnified

him from punishment, and he attempted to gain the support of the

senators and consuls, especially of Pompey. When help was not

forthcoming, he went into exile. He arrived at Thessalonica, Greece, on May 23, 58 BC. Cicero's exile caused him to fall into depression. He wrote to Atticus:

"Your pleas have prevented me from committing suicide. But what is

there to live for? Don't blame me for complaining. My afflictions

surpass any you ever heard of earlier". After the intervention of recently elected tribune Titus Annius Milo,

the senate voted in favor of recalling Cicero from exile. Clodius cast

a single vote against the decree. Cicero returned to Italy on August 5,

57 BC, landing at Brundisium. He was greeted by a cheering crowd, and, to his delight, his beloved daughter Tullia. Cicero

tried to reintegrate himself into politics, but on attacking a bill of

Caesar's proved unsuccessful. The conference at Luca in 56 BC forced

Cicero to make a recantation and pledge his support to the triumvirate.

With this a cowed Cicero retreated to his literary works. It is

uncertain whether he had any direct involvement in politics for the

following few years. The struggle between Pompey and

Julius Caesar grew more intense in 50 BC. Cicero chose to favour

Pompey, but at the same time he prudently avoided openly alienating

Caesar. When Caesar invaded Italy in 49 BC, Cicero fled Rome. Caesar,

seeking the legitimacy an endorsement by a senior senator would

provide, courted Cicero's favour, but even so Cicero slipped out of

Italy and traveled to Dyrrachium (Epidamnos), Illyria, where Pompey's staff was situated. Cicero traveled with the Pompeian forces to Pharsalus in 48 BC, though

he was quickly losing faith in the competence and righteousness of the

Pompeian lot. Eventually, he provoked the hostility of his fellow

senator Cato, who told him that he would have been of more use to the cause of the optimates if

he had stayed in Rome. After Caesar's victory at Pharsalus, Cicero

returned to Rome only very cautiously. Caesar pardoned him and Cicero

tried to adjust to the situation and maintain his political work,

hoping that Caesar might revive the Republic and its institutions. In a letter to Varro on c. April

20, 46 BC, Cicero outlined his strategy under Caesar's dictatorship.

Cicero, however, was taken completely by surprise when the Liberatores assassinated Caesar on the ides of March, 44 BC. Cicero was not included in the conspiracy, even though the conspirators were sure of his sympathy. Marcus Junius Brutus called out Cicero's name, asking him to "restore the Republic" when he lifted the bloodstained dagger after the assassination. A letter Cicero wrote in February 43 BC to Trebonius, one of the conspirators, began, "How I could wish that you had invited me to that most glorious banquet on the Ides of March"! Cicero became a popular leader during the period of instability following the assassination. He had no respect for Mark Antony, who was scheming to take revenge upon Caesar's murderers. In exchange

for amnesty for the assassins, he arranged for the Senate to agree not

to declare Caesar to have been a tyrant, which allowed the Caesarians

to have lawful support. Cicero

and Antony then became the two leading men in Rome; Cicero as spokesman

for the Senate and Antony as consul, leader of the Caesarian faction,

and unofficial executor of Caesar's public will. The two men had never

been on friendly terms and their relationship worsened after Cicero

made it clear that he felt Antony to be taking unfair liberties in

interpreting Caesar's wishes and intentions. When Octavian,

Caesar's heir and adopted son, arrived in Italy in April, Cicero formed

a plan to play him against Antony. In September he began attacking

Antony in a series of speeches he called the Philippics, after Demosthenes's denunciations of Philip II of Macedon.

Praising Octavian, he said that the young man only desired honor and

would not make the same mistake as his adoptive father. During this

time, Cicero's popularity as a public figure was unrivalled. Cicero supported Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus as governor of Cisalpine Gaul (Gallia Cisalpina) and urged the Senate to name Antony an enemy of the state. The speech of Lucius Piso, Caesar's father-in-law, delayed proceedings against Antony. Antony was later declared an enemy of the state when he refused to lift the siege of Mutina,

which was in the hands of Decimus Brutus. Cicero’s plan to drive out

Antony failed. Antony and Octavian reconciled and allied with Lepidus to form the Second Triumvirate after the successive battles of Forum Gallorum and Mutina. The Triumvirate began proscribing their

enemies and potential rivals immediately after legislating the alliance

into official existence for a term of five years with consular imperium.

Cicero and all of his contacts and supporters were numbered among the

enemies of the state, and reportedly, Octavian argued for two days

against Cicero being added to the list. Cicero

was one of the most viciously and doggedly hunted among the proscribed.

He was viewed with sympathy by a large segment of the public and many

people refused to report that they had seen him. He was caught December

7, 43 BC leaving his villa in Formiae in a litter going to the seaside where he hoped to embark on a ship destined for Macedonia. When

the assassins – Herennius (a centurion) and Popilius (a tribune) –

arrived, Cicero's own slaves said they had not seen him, but he was

given away by Philologus, a freed slave of his brother Quintus Cicero. Cicero's

last words are said to have been, "There is nothing proper about what

you are doing, soldier, but do try to kill me properly." He bowed to

his captors, leaning his head out of the litter in a gladiatorial

gesture to ease the task. By baring his neck and throat to the soldiers, he was indicating that he wouldn't resist. According to Plutarch,

Herennius first slew him, then cut off his head. On Antony's

instructions his hands, which had penned the Philippics against Antony,

were cut off as well; these were nailed and displayed along with his

head on the Rostra in the Forum Romanum according to the tradition of Marius and Sulla,

both of whom had displayed the heads of their enemies in the Forum.

Cicero was the only victim of the proscriptions to be displayed in that

manner. According to Cassius Dio (in a story often mistakenly attributed to Plutarch), Antony's wife Fulvia took

Cicero's head, pulled out his tongue, and jabbed it repeatedly with her

hairpin in final revenge against Cicero's power of speech. Cicero's son, Marcus Tullius Cicero Minor,

during his year as a consul in 30 BC, avenged his father's death

somewhat when he announced to the Senate Mark Antony's naval defeat at Actium in 31 BC by Octavian and his capable commander-in-chief Agrippa.

In the same meeting the Senate voted to prohibit all future Antonius

descendants from using the name Marcus. Octavian would later come upon

one of his grandsons reading a book by Cicero. The boy tried to conceal

the book, fearing the reaction of his grandfather. Octavian, now called

Augustus, took the book from his grandson, read a part of it, and then

handed the volume back, saying: "He was a learned man, dear child, a

learned man who loved his country."