<Back to Index>

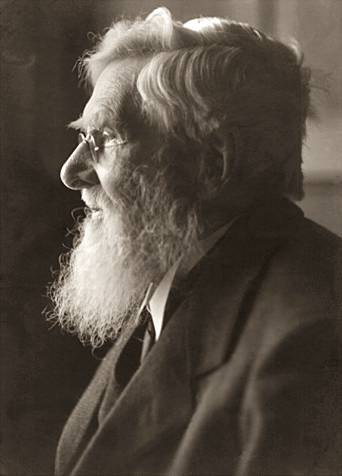

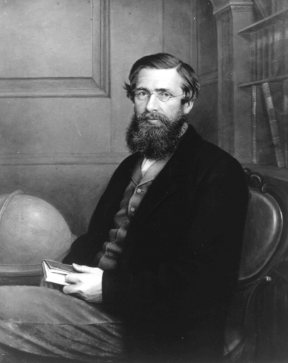

- Natural Scientist Alfred Russel Wallace, 1823

- Conductor Hans Guido von Bülow, 1830

- Dictator of Spain Miguel Primo de Rivera y Orbaneja, 2 Marqués de Estella, 1870

PAGE SPONSOR

Alfred Russel Wallace, OM, FRS (8 January 1823 – 7 November 1913) was a British naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist and biologist. He is best known for independently proposing a theory of evolution due to natural selection that prompted Charles Darwin to publish his own theory.

Wallace did extensive fieldwork, first in the Amazon River basin and then in the Malay Archipelago, where he identified the Wallace Line that divides Indonesia into

two distinct parts, one in which animals closely related to those of

Australia are common, and one in which the species are largely of Asian

origin. He was considered the 19th century's leading expert on the

geographical distribution of animal species and is sometimes called the

"father of biogeography". Wallace was one of the leading evolutionary thinkers

of the 19th century and made a number of other contributions to the

development of evolutionary theory besides being co-discoverer of

natural selection. These included the concept of warning colouration in animals, and the Wallace effect, a hypothesis on how natural selection could contribute to speciation by encouraging the development of barriers against hybridization. Wallace was strongly attracted to unconventional ideas. His advocacy of Spiritualism and his belief in a non-material origin for

the higher mental faculties of humans strained his relationship with

the scientific establishment, especially with other early proponents of

evolution. In addition to his scientific work, he was a social activist

who was critical of what he considered to be an unjust social and

economic system in 19th century Britain. His interest in biogeography

resulted in his being one of the first prominent scientists to raise

concerns over the environmental impact of human activity. Wallace was a

prolific author who wrote on both scientific and social issues; his

account of his adventures and observations during his explorations in Indonesia and Malaysia, The Malay Archipelago, was one of the most popular and influential journals of scientific exploration published during the 19th century. Wallace was born in the Welsh village of Llanbadoc, near Usk, Monmouthshire. He

was the seventh of eight children of Thomas Vere Wallace and Mary Anne

Greenell. Thomas Wallace was of Scottish ancestry. His family, like

many Scottish Wallaces, claimed a connection to William Wallace, a Scottish leader during the Wars of Scottish Independence in the 13th century. Thomas

Wallace received a law degree, but never actually practiced law. He

inherited some income-generating property, but bad investments and

failed business ventures resulted in a steady deterioration of the

family's financial position. His mother was from a respectable

middle-class English family from Hertford, north of London. When Wallace was five years old, his family moved to Hertford. There he attended Hertford Grammar School until financial difficulties forced his family to withdraw him in 1836. Wallace

then moved to London to live and work with his older brother John, a

19-year-old apprentice builder. This was

a stopgap measure until William, his oldest brother, was ready to take

him on as an apprentice surveyor. While there, he attended lectures and read books at the London Mechanics Institute. Here he was exposed to the radical political ideas of the Welsh social reformer Robert Owen and Thomas Paine. He left London in 1837 to live with William and work as his apprentice for six years. At the end of 1839, they moved to Kington, Hereford, near the Welsh border before eventually settling at Neath in Glamorgan in Wales. Between 1840 and 1843, Wallace did surveying work in the countryside of the west of England and Wales. By

the end of 1843, William's business had declined due to difficult

economic conditions. Wallace left in January, aged 20. After a brief period of unemployment, he was hired as a master at the Collegiate School in Leicester to teach drawing, mapmaking, and surveying. Wallace spent a lot of time at the Leicester library where he read An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus and where one evening he met the entomologist Henry Bates. Bates was only 19 years old, but had already published a paper on beetles in the journal Zoologist. He befriended Wallace and started him collecting insects. William

died in March 1845, and Wallace left his teaching position to assume

control of his brother's firm in Neath, but he and his brother John

were unable to make the business work. After a couple of months,

Wallace found work as a civil engineer for a nearby firm that was

working on a survey for a proposed railway in the Vale of Neath.

Wallace's work on the survey involved spending a lot of time outdoors

in the countryside, allowing him to indulge his new passion for

collecting insects. Wallace was able to persuade his brother John to

join him in starting another architecture and civil engineering firm,

which carried out a number of projects, including the design of a

building for the Mechanics' Institute of Neath. William Jevons, the

founder of that institute, was impressed by Wallace and persuaded him

to give lectures there on science and engineering. In the autumn of

1846, he, aged 23, and John were able to purchase a cottage near Neath,

where they lived with their mother and sister Fanny (his father had

died in 1843). During this period, he read avidly, exchanging letters with Bates about the anonymous evolutionary treatise Vestiges of the Natural History of Creation, Charles Darwin's Journal, and Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology. Inspired by the chronicles of earlier traveling naturalists, including Alexander von Humboldt, Charles Darwin and William Henry Edwards, Wallace decided that he too wanted to travel abroad as a naturalist. In 1848, Wallace and Henry Bates left for Brazil aboard the Mischief. Their intention was to collect insects and other animal specimens in the Amazon rainforest and sell them to collectors back in the United Kingdom. They also hoped to gather evidence of the transmutation of species. Wallace and Bates spent most of their first year collecting near Belém do Pará,

then explored inland separately, occasionally meeting to discuss their

findings. In 1849, they were briefly joined by another young explorer,

botanist Richard Spruce, along with Wallace's younger brother Herbert. Herbert left soon thereafter (dying two years later from yellow fever), but Spruce, like Bates, would spend over ten years collecting in South America. Wallace continued charting the Rio Negro for

four years, collecting specimens and making notes on the peoples and

languages he encountered as well as the geography, flora, and fauna. On 12 July 1852, Wallace embarked for the UK on the brig Helen. After twenty-eight days at sea, balsam in

the ship's cargo caught fire and the crew was forced to abandon ship.

All of the specimens Wallace had on the ship, the vast majority of what

he had collected during his entire trip, were lost. He could only save

part of his diary and a few sketches. Wallace and the crew spent ten

days in an open boat before being picked up by the brig Jordeson. After

his return to the UK, Wallace spent eighteen months in London living on

the insurance payment for his lost collection and selling a few

specimens that had been shipped back to Britain prior to his starting

his exploration of the Rio Negro. During this period, despite having

lost almost all of the notes from his South American expedition, he

wrote six academic papers (which included "On the Monkeys of the

Amazon") and two books; Palm Trees of the Amazon and Their Uses and Travels on the Amazon. He also made connections with a number of other British naturalists — most significantly, Darwin. From 1854 to 1862, age 31 to 39, Wallace travelled through the Malay Archipelago or East Indies (now Malaysia and Indonesia),

to collect specimens for sale and to study nature. His observations of

the marked zoological differences across a narrow strait in the

archipelago led to his proposing the zoogeographical boundary now known

as the Wallace line.

Wallace collected more than 125,000 specimens in the Malay Archipelago

(more than 80,000 beetles alone). More than a thousand of them

represented species new to science. One of his better-known species descriptions during this trip is that of the gliding tree frog Rhacophorus nigropalmatus, known as Wallace's flying frog. While he was exploring the archipelago, he refined his thoughts about evolution and had his famous insight on natural selection.

In 1858 he sent an article outlining his theory to Darwin; it was

published, along with a description of Darwin's own theory, in the same

year. Accounts of his studies and adventures there were eventually published in 1869 as The Malay Archipelago. The Malay Archipelago became one of the most popular journals of scientific exploration of the 19th

century, kept continuously in print by its original publisher

(Macmillan) into the second decade of the 20th century. It was praised

by scientists such as Darwin (to whom the book was dedicated), and Charles Lyell, and by non-scientists such as the novelist Joseph Conrad, who called it his "favorite bedside companion" and used it as source of information for several of his novels, especially Lord Jim. In

1862, Wallace returned to the UK, where he moved in with his sister

Fanny Sims and her husband Thomas. While recovering from his travels,

Wallace organized his collections and gave numerous lectures about his

adventures and discoveries to scientific societies such as the Zoological Society of London. Later that year, he visited Darwin at Down House, and became friendly with both Charles Lyell and Herbert Spencer. During

the 1860s, Wallace wrote papers and gave lectures defending natural

selection. He also corresponded with Darwin about a variety of topics,

including sexual selection, warning colouration, and the possible effect of natural selection on hybridization and the divergence of species. In 1865, he began investigating spiritualism. After

a year of courtship, Wallace became engaged in 1864 to a young woman

whom, in his autobiography, he would only identify as Miss L. However,

to Wallace's great dismay, she broke off the engagement. In 1866, Wallace married Annie Mitten. Wallace had been introduced to Mitten through the botanist Richard Spruce, who had befriended Wallace in Brazil and who was also a good friend of Annie Mitten's father, William Mitten, an expert on mosses. In 1872, Wallace built the Dell, a house of concrete, on land he leased in Grays in

Essex, where he lived until 1876. The Wallaces had three children:

Herbert (1867 – 1874) who died in childhood, Violet (1869 – 1945), and

William (1871 – 1951).

In

the late 1860s and 1870s, Wallace was very concerned about the

financial security of his family. While he was in the Malay

Archipelago, the sale of specimens had brought in a considerable amount

of money, which had been carefully invested by the agent who sold the

specimens for Wallace. However, on his return to the UK, Wallace made a

series of bad investments in railways and mines that squandered most of

the money, and he found himself badly in need of the proceeds from the

publication of The Malay Archipelago. Despite

assistance from his friends, he was never able to secure a permanent

salaried position such as curatorship of a museum. In order to remain

financially solvent, Wallace worked grading government examinations,

wrote 25 papers for publication between 1872 and 1876 for various

modest sums, and was paid by Lyell and Darwin to help edit some of

their own works. In 1876, Wallace needed a £500 advance from the publisher of The Geographical Distribution of Animals to avoid having to sell some of his personal property. Darwin

was very aware of Wallace's financial difficulties and lobbied long and

hard to get Wallace awarded a government pension for his lifetime

contributions to science. When the £200

annual pension was awarded in 1881, it helped to stabilize Wallace's

financial position by supplementing the income from his writings. John Stuart Mill was impressed by remarks criticizing English society that Wallace had included in The Malay Archipelago.

Mill asked him to join the general committee of his Land Tenure Reform

Association, but the association dissolved after Mill's death in 1873.

Wallace wrote only a handful of articles on political and social issues

between 1873 and 1879, when, aged 56, he entered the debates over trade

policy and land reform in

earnest. He believed that rural land should be owned by the state and

leased to people who would make whatever use of it that would benefit

the largest number of people, thus breaking the often-abused power of

wealthy landowners in English society. In 1881, Wallace was elected as

the first president of the newly formed Land Nationalisation Society.

In the next year, he published a book, Land Nationalisation; Its Necessity and Its Aims, on the subject. He criticized the UK's free trade policies for the negative impact they had on working class people. In 1889, Wallace read Looking Backward by Edward Bellamy and declared himself a socialist. These ideas led him to oppose both social Darwinism and eugenics,

ideas supported by other prominent 19th century evolutionary thinkers,

on the grounds that contemporary society was too corrupt and unjust to

allow any reasonable determination of who was fit or unfit. In 1898, Wallace wrote a paper advocating a pure paper money system, not backed by silver or gold, which impressed the economist Irving Fisher so much that he dedicated his 1920 book Stabilizing the Dollar to Wallace. Wallace wrote extensively on other social topics including his support for women's suffrage, and the dangers and wastefulness of militarism. Wallace continued his social activism for the rest of his life, publishing the book The Revolt of Democracy just weeks before his death. Wallace continued his scientific work in parallel with his social commentary. In 1880, he published Island Life as a sequel to The Geographic Distribution of Animals. In November 1886, Wallace began a ten-month trip to the United States to

give a series of popular lectures. Most of the lectures were on

Darwinism (evolution and natural selection), but he also gave speeches

on biogeography, spiritualism, and socio-economic reform. During the trip, he was reunited with his brother John who had emigrated to California years before. He also spent a week in Colorado, with the American botanist Alice Eastwood as his guide, exploring the flora of the Rocky Mountains and gathering evidence that would lead him to a theory on how glaciation might

explain certain commonalities between the mountain flora of Europe,

Asia and North America, which he published in 1891 in the paper

"English and American Flowers". He met many other prominent American

naturalists and viewed their collections. His 1889 book Darwinism used information he collected on his American trip, and information he had compiled for the lectures.

On 7 November 1913, Wallace died at home in the country house he called Old Orchard, which he had built a decade earlier. He was 90 years old. His death was widely reported in the press. The New York Times called

him "the last of the giants belonging to that wonderful group of

intellectuals that included, among others, Darwin, Huxley, Spencer,

Lyell, and Owen, whose daring investigations revolutionized and

evolutionized the thought of the century." Another commentator in the

same edition said “No apology need be made for the few literary or

scientific follies of the author of that great book on the 'Malay

Archipelago'.” Some of Wallace's friends suggested that he be buried in Westminster Abbey, but his wife followed his wishes and had him buried in the small cemetery at Broadstone, Dorset. Several

prominent British scientists formed a committee to have a medallion of

Wallace placed in Westminster near where Darwin had been buried. The

medallion was unveiled on 1 November 1915.