<Back to Index>

- Engineer James Watt, 1736

- Painter Paul Cézanne, 1839

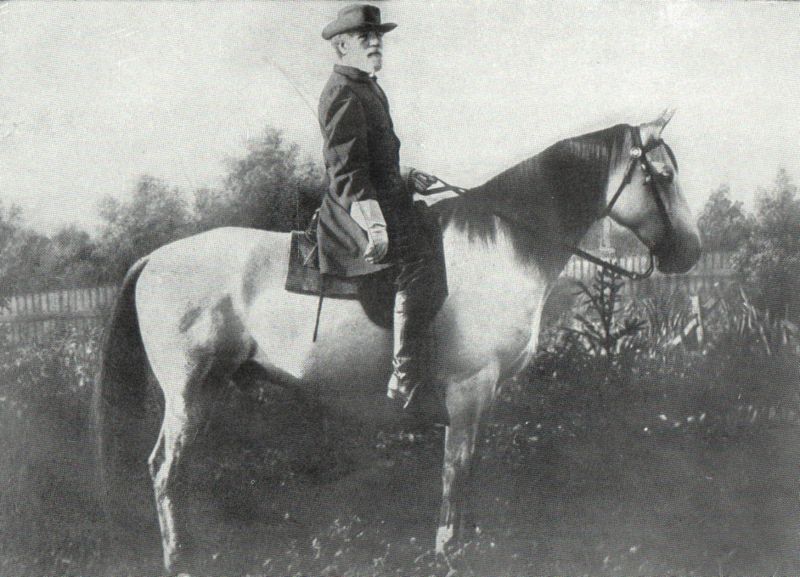

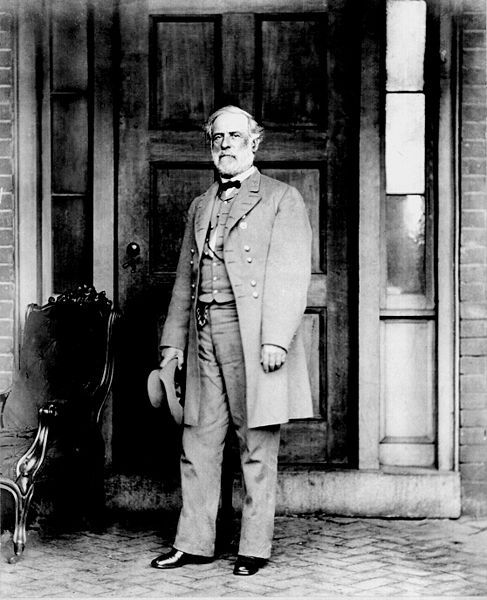

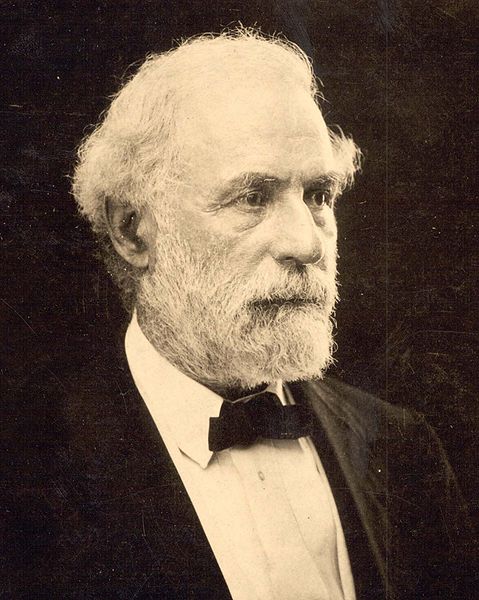

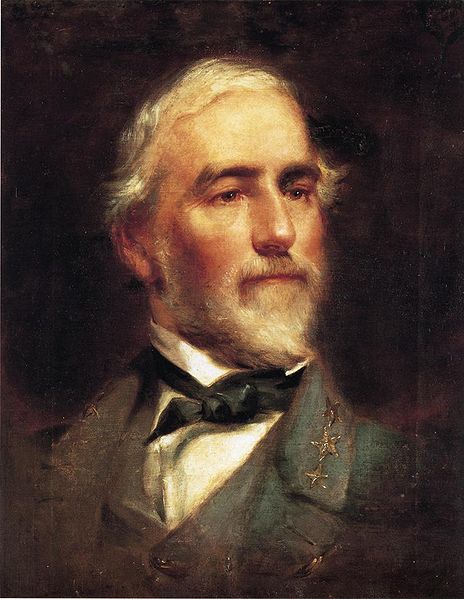

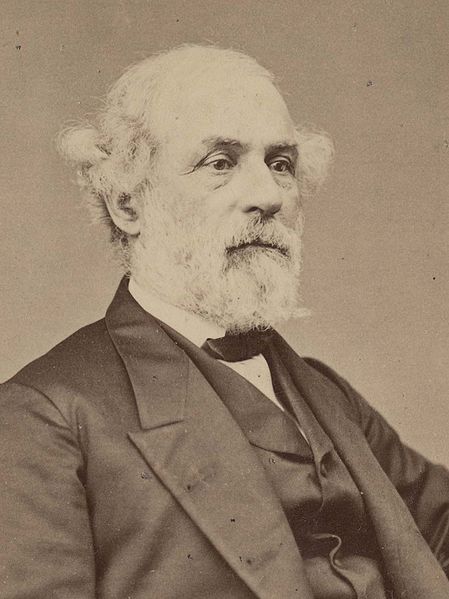

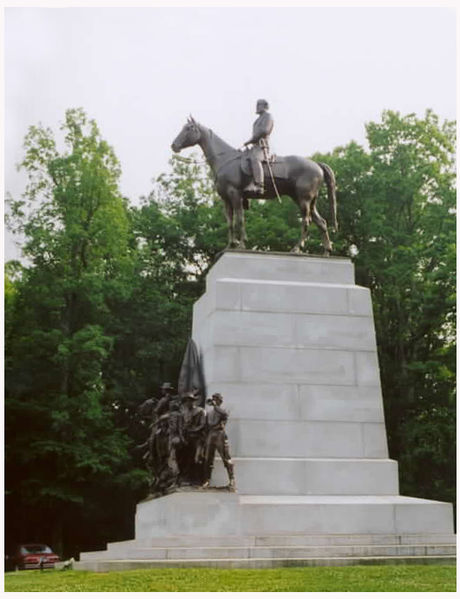

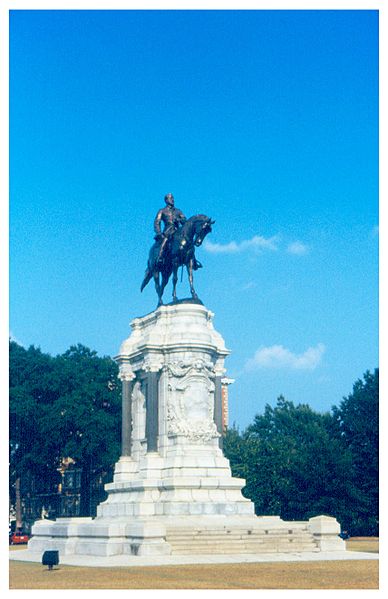

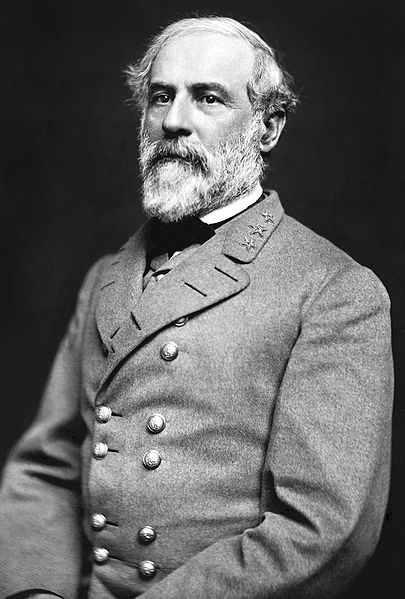

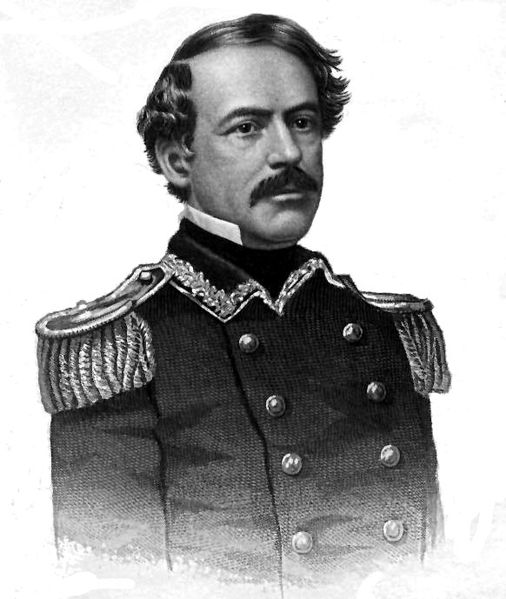

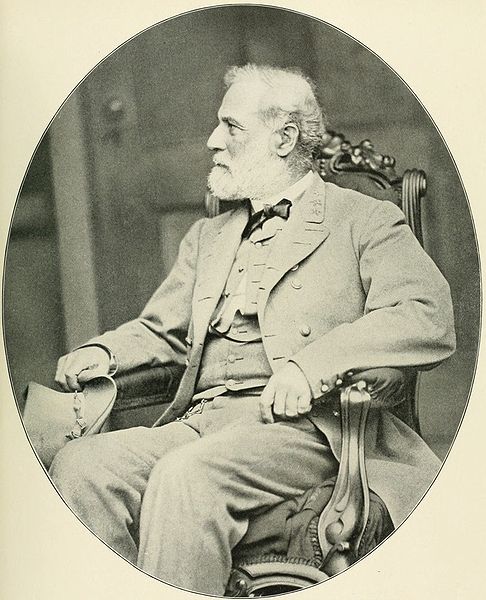

- General Robert Edward Lee, 1807

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a career United States Army officer, a combat engineer, becoming the outstanding general of the Confederate army in the American Civil War and a postwar icon of the South's "lost cause."

A top graduate of West Point, Lee distinguished himself as an exceptional soldier in the U.S. Army for thirty-two years. He is best known for commanding the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in the American Civil War. In early 1861, President Abraham Lincoln invited

Lee to take command of the entire Union Army. Lee declined because his

home state of Virginia was seceding from the Union, despite Lee's

wishes. When Virginia seceded from the Union in

April 1861, Lee chose to follow his home state. Lee's eventual role in

the newly established Confederacy was to serve as a senior military

adviser to President Jefferson Davis.

Lee's first field command for the Confederate States came in June 1862

when he took command of the Confederate forces in the East (which Lee

himself renamed the "Army of Northern Virginia"). Lee

immediately emerged as the swiftest and shrewdest battlefield tactician

of the war, as typified by many victories such as the Battle of Fredericksburg (1862), Battle of Chancellorsville (1863), Battle of Cold Harbor (1864), Seven Days Battles, and the Second Battle of Bull Run.

His strategic vision was more dubious -- his invasions of the North in

1862 and 1863 were based on the false assumption that Northern morale

was weak and could be shattered by rebel victories. They produced

disastrous defeats at Antietam (1862) and Gettysburg (1863). However, due to ineffectual pursuit by the commander of Union forces, Major General George Meade,

Lee escaped again to Virginia. His failure to protect Vicksburg in 1863

cost the Confederacy control of its western regions. Nevertheless Lee's

brilliant defensive maneuvers stopped the Union offenses one after

another, as a series of Union commanders failed to win a single major

battle in Virginia. In the spring of 1864, the new Union commander, Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant, began a series of campaigns to wear down Lee's army. In the Overland Campaign of 1864 and the Siege of Petersburg in

1864 – 1865, Lee inflicted heavy casualties on Grant's larger army, but

was unable to replace his own losses. In early April 1865, Lee's

depleted forces were turned from their entrenchments near the

Confederate capital of Richmond, Virginia, and he began a strategic retreat. Lee's subsequent surrender at Appomattox Courthouse on

April 9, 1865 represented the loss of only one of the remaining

Confederate field armies, but it was a psychological blow from which

the South could not recover. By June 1865, all of the remaining

Confederate armies had capitulated. Lee's victories against superior

forces won him enduring fame as a crafty and daring battlefield tactician, but some of his strategic decisions,

such as invading the North in 1862 and 1863, have been criticized by

many military historians. In the final months of the Civil War, as

manpower reserves drained away, Lee adopted a plan to arm slaves to

fight on behalf of the Confederacy, but this came too late to change

the outcome of the war. After Appomattox, Lee discouraged Southern

dissenters from starting a guerrilla campaign to continue the war, and

encouraged reconciliation between the North and the South. After the

war, as a college President, Lee supported President Andrew Johnson's program of Reconstruction and inter-sectional friendship, while opposing the Radical Republican proposals

to give freed slaves the vote and take the vote away from

ex-Confederates. He urged them to re-think their position between the

North and the South, and the reintegration of former Confederates into

the nation's political life. Lee became the great Southern hero of the

war, and his popularity grew in the North as well after his death in

1870. He remains an iconic figure of American military leadership. Lee was born at Stratford Hall Plantation in Westmoreland County, Virginia, the son of Major General Henry Lee III "Light Horse Harry" (1756 – 1818), Governor of Virginia, and his second wife, Anne Hill Carter (1773 – 1829). The family was famous. Lee's paternal ancestors were among the earliest settlers in Virginia. His mother grew up at Shirley Plantation, one of the most elegant homes in Virginia.

Lee's father, a tobacco planter, suffered severe financial reverses

from failed investments. Unable to exercise self-control or take care

of his family, and he abandoned them.

Lee's father died when the boy was 11 years old, leaving the family

deeply in debt. Since an older brother inherited the Stratford Hall

Plantation, Lee and his family moved to Alexandria, Virginia,

where Lee grew up in a series of relatives' houses. Lee attended

Alexandria Academy, where he studied Greek, Latin, algebra and

geometry; he was a top student. His mother, a devout Christian, oversaw

his religious instruction at Christ Episcopal Church in Alexandria. He entered the United States Military Academy in

1825 and became the first cadet to achieve the rank of sergeant at the

end of his first year. When he graduated in 1829 he was at the head of

his class in artillery and tactics, and shared the distinction with

five other cadets of having received no demerits during the four-year

course of instruction. Overall, he ranked second in his class of 46. He was commissioned as a brevet second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers. Lee served for just over 17 months at Fort Pulaski on Cockspur Island, Georgia. In 1831 he was transferred to Fort Monroe at the tip of the Virginia Peninsula and

played a major role in the final construction of Fort Monroe and its

opposite, Fort Calhoun. Fort Monroe was completely surrounded by a moat. Fort Calhoun, later renamed Fort Wool, was built on a man-made island across the navigational channel from Old Point Comfort in the middle of the mouth of Hampton Roads. When construction was completed in 1834, Fort Monroe was referred to as the "Gibraltar of Chesapeake Bay." While he was stationed at Fort Monroe, he married. Lee served as an assistant in the chief engineer's office in Washington, D.C. from 1834 to 1837, but spent the summer of 1835 helping to lay out the state line between Ohio and Michigan. As a first lieutenant of engineers in 1837, he supervised the engineering work for St. Louis harbor and for the upper Mississippi and Missouri rivers. Among his projects was blasting a channel through the Des Moines Rapids on the Mississippi by Keokuk, Iowa,

where the Mississippi's mean depth of 2.4 feet (0.7 m) was

the upper limit of steamboat traffic on the river. His work there

earned him a promotion to captain. Circa 1842, Captain Robert E. Lee arrived as Fort Hamilton's post engineer. While he was stationed at Fort Monroe, he married Mary Anna Randolph Custis (1808 – 1873), great-granddaughter of Martha Washington by her first husband Daniel Parke Custis, and step-great-granddaughter of George Washington, the first president of the United States. Mary was the only surviving child of George Washington Parke Custis, George Washington's stepgrandson, and Mary Lee Fitzhugh Custis, daughter of William Fitzhugh and Ann Randolph. They were married on June 30, 1831 at Arlington House,

her parents' house just across from Washington, D.C. The 3rd U.S.

Artillery served as honor guard at the marriage. They eventually had

seven children, three boys and four girls. All the children survived

him except for Annie, who died in 1862. They are all buried with their

parents in the crypt of the Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University in Lexington, Virginia. Lee is also related to Helen Keller, through Helen's mother, Kate. On May 1, 1864, General Lee was at General A.P. Hill's daughters baptism, Lucy Lee Hill, to serve as her Godfather. This is referenced in the painting Tender is the Heart by Mort Künstler. Lee distinguished himself in the Mexican–American War (1846 – 1848). He was one of Winfield Scott's chief aides in the march from Veracruz to Mexico City.

He was instrumental in several American victories through his personal

reconnaissance as a staff officer; he found routes of attack that the Mexicans had not defended because they thought the terrain was impassable. He was promoted to brevet major after the Battle of Cerro Gordo on April 18, 1847. He also fought at Contreras, Churubusco, and Chapultepec,

and was wounded at the last. By the end of the war, he had received

additional brevet promotions to Lieutenant Colonel and Colonel, but his

permanent rank was still Captain of Engineers and he would remain a

Captain until his transfer to the cavalry in 1855. For the first time Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant met

and worked with each other during the Mexican-American War. Both Lee

and Grant participated in the Scott's march from the coastal town of

Vera Cruz to Mexico City. Grant gained wartime experience as a quartermaster, Lee as an engineer who positioned troops and artillery. Both did their

share of actual fighting. At Vera Cruz, Lee earned a commendation for

"greatly distinguished" service. Grant was among the leaders at the

bloody assault at Molino del Rey,

and both soldiers were among the forces that entered Mexico City. Close

observations of their commanders constituted a learning process for

both Lee and Grant. The Mexican-American War concluded on February 2, 1848. After the Mexican War, Lee spent three years at Fort Carroll in Baltimore harbor.

During this time his service was interrupted by other duties, among

them surveying/updating maps in Florida. Lee declined an offer from

Cuban rebels to lead their fight against Spain. The

1850s were a difficult time for Lee, with his long absences from home,

the increasing disability of his wife, and his often morbid concern

with his personal failures. In 1852 was appointed Superintendent of the Military Academy at West Point;

he was reluctant to enter what he called a "snake pit" but the War

Department insisted and he obeyed. His wife occasionally came to visit.

During his three years at West Point, Brevet Colonel Robert E. Lee

improved the buildings and courses, and spent a lot of time with the

cadets. Lee's oldest son, George Washington Custis Lee, attended West Point during his tenure. Custis Lee graduated in 1854, first in his class. Lee

was greatly relieved to receive a long-awaited promotion as

second-in-command of the Second Cavalry regiment in Texas in 1855. It

meant leaving the Engineering Corps and its sequence of staff jobs for

the combat command he really wanted. He served under Colonel Albert Sidney Johnston at Camp Cooper, Texas; their mission was to protect settlers from attacks by the Apache and the Comanche. The death in 1857 of his father in law George Washington Parke Custis created

a major crisis, as Lee had to assume the main burden of executing the

will. The Curtis estate was in disarray, with vast landholdings and

hundreds of slaves balanced against huge debts. The plantations had

been poorly managed and were losing money. Lee took several leaves of

absence from the army and became a planter and eventually straightened

out the estate. On June 24, 1859, Lee was accused by the New York Tribune of

having three run away slaves whipped; himself personally whipping a

female slave. Lee did not respond to the attack until 1866, claiming in

a letter the accusation was not true. The Curtis will called for

emancipating the slaves within five years, but state law required they

be funded in as livelihood outside Virginia, and that was impossible

until the debts were paid off. They were all emancipated by 1862. Since

the end of the Civil War, it has often been suggested that Lee was in

some sense opposed to slavery. In the period following the Civil War and Reconstruction, and after his death, Lee became a central figure in the Lost Cause interpretation

of the war, and as succeeding generations came to look on slavery as a

terrible immorality, the idea that Lee had always somehow opposed it

helped maintain his stature as a symbol of Southern honor and national

reconciliation. The

evidence cited in favor of the claim that Lee opposed slavery included

his direct statements and his actions before and during the war,

including Lee's support of the work by his wife and her mother to

liberate slaves and fund their move to Liberia, the success of his wife and daughter in setting up an illegal school for slaves on the Arlington plantation,

the freeing of Custis' slaves in 1862, and his insistence in 1864-65

that the Confederacy enroll slaves in Lee's Army, with manumission

offered as an eventual reward for good service. In December 1864, Lee was shown a letter by Louisiana Senator Edward Sparrow, written by General St. John R. Liddell, which noted that Lee would be hard-pressed in the interior of Virginia by spring, and the need to consider Patrick Cleburne's plan to emancipate the slaves and put all men in the army that were

willing to join. Lee was said to have agreed on all points and desired

to get black soldiers, saying that "he could make soldiers out of any

human being that had arms and legs."

When Texas seceded from the Union in February 1861, General David E. Twiggs surrendered

all the American forces (about 4,000 men, including Lee, and commander

of the Department of Texas) to the Texans. Twiggs immediately resigned

from the U.S. Army and was made a Confederate general. Lee went back

to Washington, and was appointed Colonel of the First Regiment of

Cavalry in March 1861. Lee's Colonelcy was signed by the new President,

Abraham Lincoln. Three weeks after his promotion, Colonel Lee was

offered a senior command (with the rank of Major General) in the

expanding Army to fight the Southern States that had left the Union.

Lee

privately ridiculed the Confederacy in letters in early 1861,

denouncing secession as "revolution" and a betrayal of the efforts of

the founders. The commanding general of the Union Army, Winfield Scott, told Lincoln he wanted Lee for a top command. Lee accepted a promotion to colonel on March 28. Lee

had earlier been asked by one of his lieutenants if he intended to

fight for the Confederacy or the Union, to which he replied, "I shall

never bear arms against the Union, but it may be necessary for me to

carry a musket in the defense of my native state, Virginia, in which

case I shall not prove recreant to my duty." Meanwhile,

Lee ignored an offer of command from the CSA. After Lincoln's call for

troops to put down the rebellion, it was obvious that Virginia would

quickly secede. So Lee turned down an April 18 offer to become a major

general in the U.S. Army, resigned on April 20 and took up command of

the Virginia state forces on April 23. At

the outbreak of war, Lee was appointed to command all of Virginia's

forces, but upon the formation of the Confederate States Army, he was named one of its first five full generals.

Lee did not wear the insignia of a Confederate general, but only the

three stars of a Confederate colonel, equivalent to his last U.S. Army

rank. He did not intend to wear a general's insignia until the Civil

War had been won and he could be promoted, in peacetime, to general in

the Confederate Army. Lee's first field assignment was commanding Confederate forces in western Virginia, where he was defeated at the Battle of Cheat Mountain and was widely blamed for Confederate setbacks. He

was then sent to organize the coastal defenses along the Carolina and

Georgia seaboard, where he was hampered by the lack of an effective

Confederate navy. Once again blamed by the press, he became military

adviser to Confederate Pres. Jefferson Davis, former U.S. Secretary of War. While in Richmond,

Lee was ridiculed as the 'King of Spades' for his excessive digging of

trenches around the capitol. These trenches would later play an

important role in battles near the end of the war. In the spring of 1862, during the Peninsula Campaign, the Union Army of the Potomac under General George B. McClellan advanced upon Richmond from Fort Monroe, eventually reaching the eastern edges of the Confederate capital along the Chickahominy River. Following the wounding of Gen. Joseph E. Johnston at the Battle of Seven Pines, on June 1, 1862, Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, his first opportunity to lead an army in the field. Newspaper

editorials of the day objected to his appointment due to concerns that

Lee would not be aggressive and would wait for the Union army to come

to him. Early in the war his men called him "Granny Lee" because of his

allegedly timid style of command. After the Seven Days Battles until

the end of the war his men called him simply "Marse Robert." He oversaw

substantial strengthening of Richmond's defenses during the first three

weeks of June and then launched a series of attacks, the Seven Days Battles,

against McClellan's forces. Lee's attacks resulted in heavy Confederate

casualties and they were marred by clumsy tactical performances by his

subordinates, but his aggressive actions unnerved McClellan, who

retreated to a point on the James River where Union naval forces were in control. These successes led to a rapid

turn-around of public opinion and the newspaper editorials quickly

changed their tune on Lee's aggressiveness. After McClellan's retreat, Lee defeated another Union army at the Second Battle of Bull Run.

Within 90 days of taking command, Lee had run McClellan off the

Peninsula, defeated Pope at Second Manassas, and the battle lines had

moved from 6 miles outside Richmond, to 20 miles outside Washington.

Instead of a quick end to the war that the Peninsula Campaign had

promised in its early stages, the war would go on for almost another 3

years and claim a half million more lives. He then invaded Maryland,

hoping to replenish his supplies and possibly influence the Northern

elections to fall in favor of ending the war. McClellan's men recovered

a lost order that revealed Lee's plans. McClellan always exaggerated

Lee's forces, but now he knew the Confederate army was divided and

could be destroyed by an all-out attack at Antietam. Yet McClellan was too slow in moving, not realizing Lee had been

informed by a spy that McClellan had the plans. Lee urgently recalled Stonewall Jackson and

in the bloodiest day of the war, Lee withstood the Union assaults. He

withdrew his battered army back to Virginia while President Abraham Lincoln used the reverse as sufficient pretext to announce the Emancipation Proclamation to put the Confederacy on the diplomatic and moral defensive. Disappointed by McClellan's failure to destroy Lee's army, Lincoln named Ambrose Burnside as commander of the Army of the Potomac. Burnside ordered an attack across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg.

Delays in getting bridges built across the river allowed Lee's army

ample time to organize strong defenses, and the attack on December 12,

1862, was a disaster for the Union. Lincoln then named Joseph Hooker commander of the Army of the Potomac. Hooker's advance to attack Lee in May, 1863, near Chancellorsville, Virginia,

was defeated by Lee and Stonewall Jackson's daring plan to divide the

army and attack Hooker's flank. It was a victory over a larger force,

but it also came with a great cost; Jackson, one of Lee's best

subordinates, was accidentally wounded by his own troops, and soon

after died of pneumonia. In

the summer of 1863, Lee invaded the North again, hoping for a Southern

victory that would shatter Northern morale. A young Pennsylvanian woman

who watched from her porch as General Lee passed by remarked, "I wish

he were ours." He encountered Union forces under George G. Meade at the three-day Battle of Gettysburg in

Pennsylvania in July; the battle would produce the largest number of

casualties in the American Civil War. Some of his subordinates were new

and inexperienced in their commands, J.E.B. Stuart's

cavalry was out of the area, slightly ill, and thus Lee was less than

comfortable with how events were unfolding. While the first day of

battle was controlled by the Confederates, key terrain which should

have been taken by General Ewell was not. The Second day ended with the

Confederates unable to break the Union position, and the Union more

solidified. Lee's decision on the third day, against the sound judgment

of his best corps commander General Longstreet, to launch a massive

frontal assault on the center of the Union line was disastrous. The

assault known as Pickett's Charge —

was repulsed and resulted in heavy Confederate losses. The general rode

out to meet his retreating army and proclaimed, "All this has been MY

my fault." Lee

was compelled to retreat. Despite flooded rivers that blocked his

retreat, he escaped Meade's ineffective pursuit. Following his defeat

at Gettysburg, Lee sent a letter of resignation to Pres. Davis on

August 8, 1863, but Davis refused Lee's request. That fall, Lee and

Meade met again in two minor campaigns that did little to change the

strategic standoff. The Confederate Army never fully recovered from the

substantial losses incurred during the 3-day battle in southern

Pennsylvania. The historian Shelby Foote stated, "Gettysburg was the price the South paid for having Robert E. Lee as commander." In 1864 the new Union general-in-chief, Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, sought to use his large advantages in manpower and material resources to destroy Lee's army by attrition,

pinning Lee against his capital of Richmond. Lee successfully stopped

each attack, but Grant with his superior numbers kept pushing each time

a bit farther to the southeast. These battles in the Overland Campaign included the Wilderness, Spotsylvania Court House and Cold Harbor. Grant eventually was able to stealthily move his army across the James River. After stopping a Union attempt to capture Petersburg, Virginia,

a vital railroad link supplying Richmond, Lee's men built elaborate

trenches and were besieged in Petersburg. (This development presaged

the trench warfare of World War I, exactly 50 years later.) He

attempted to break the stalemate by sending Jubal A. Early on a raid through the Shenandoah Valley to Washington, D.C., but was defeated early on by the superior forces of Philip Sheridan. The Siege of Petersburg lasted

from June 1864 until March 1865, with Lee's outnumbered and poorly

supplied army shrinking daily because of desertions by disheartened

Confederates. On January 31, 1865, Lee was promoted to general-in-chief of Confederate forces. As

the South ran out of manpower the issue of arming the slaves became

paramount. By late 1864 the army so dominated the Confederacy that

civilian leaders were unable to block the military's proposal, strongly

endorsed by Lee, to arm and train slaves in Confederate uniform for

combat. In return for this service, slave soldiers and their families

would be emancipated. Lee explained, "We should employ them without

delay ... [along with] gradual and general emancipation." The first

units were in training as the war ended. As the Confederate army was devastated by casualties, disease and desertion, the Union attack on Petersburg succeeded

on April 2, 1865. Lee abandoned Richmond and retreated west. His forces

were surrounded and he surrendered them to Grant on April 9, 1865, at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Other Confederate armies followed suit and the war ended. The day after his surrender, Lee issued his Farewell Address to his army. Lee

resisted calls by some officers to reject surrender and allow small

units to melt away into the mountains, setting up a lengthy guerrilla

war. He insisted the war was over and energetically campaigned for

inter-sectional reconciliation. "So far from engaging in a war to

perpetuate slavery, I am rejoiced that slavery is abolished. I believe

it will be greatly for the interests of the South."

After

the war, Lee was not arrested or punished, but he did lose the right to

vote as well as some property. Lee supported President Johnson's plan of Reconstruction,

but joined with Democrats in opposing the Radical Republicans who

demanded punitive measures against the South and distrusted its

commitment to the abolition of slavery and, indeed, distrusted the

region's loyalty to United States. Lee supported civil rights for all,

as well as a system of free public schools for blacks, but dissented

regarding black suffrage. Most of all he became an icon of

reconciliation between the North and South, and the reintegration of

former Confederates into the national fabric. Lee's prewar family home, the Custis-Lee Mansion was seized by Union forces during the war and turned into Arlington National Cemetery. The family was compensated in 1883. Lee

hoped to retire to a farm of his own, but he was too much a regional

symbol to live in obscurity. He accepted an offer to serve as the

president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University) in Lexington, Virginia,

and served from October 1865 until his death. The Trustees used his

famous name in large-scale fund-raising appeals and Lee transformed

Washington College in to a leading Southern college. Lee was well liked

by the students, which enabled him to announce an "honor system" like West Point's, explaining "We have but one rule here, and it is that every student be a gentleman."

To speed up national reconciliation Lee recruited students from the

North and made certain they were well treated on campus and in town.

Several

glowing appraisals of Lee's tenure as college president have survived,

depicting the dignity and respect he commanded among all. Previously,

most students had been obliged to occupy the campus dormitories, while

only the most mature were allowed to live off-campus. Lee quickly

reversed this rule, requiring most students to board off-campus, and

allowing only the most mature to live in the dorms as a mark of

privilege; the results of this policy were considered a success. A

typical account by a professor there states that "the students fairly

worshipped him, and deeply dreaded his displeasure; yet so kind,

affable, and gentle was he toward them that all loved to approach

him... No student would have dared to violate General Lee's expressed

wish or appeal; if he had done so, the students themselves would have

driven him from the college." Elsewhere, the same professor recalls the

following: President

Andrew Johnson, in a proclamation dated December 25, 1868 (15 Stat.

711), gave an unconditional pardon to those who "directly or

indirectly" rebelled against the United States. Lee,

with this full amnesty pardon by President Johnson, could not be held

liable for treason or insurrection against the United States. Lee was posthumously officially reinstated as a United States citizen by President Gerald Ford in 1975. Lee,

who had opposed secession and remained mostly indifferent to politics

before the Civil War, supported President Johnson's plan of Presidential Reconstruction that

took effect in 1865–66. However, he opposed the Congressional

Republican program that took effect in 1867. In February 1866, he was

called to testify before the Joint Congressional Committee on

Reconstruction in Washington, where he expressed support for President Andrew Johnson's

plans for quick restoration of the former Confederate states, and

argued that restoration should return, as far as possible, the status

quo ante in the Southern states' governments (with the exception of

slavery). Lee

told the Committee, "...every one with whom I associate expresses kind

feelings towards the freedmen. They wish to see them get on in the

world, and particularly to take up some occupation for a living, and to

turn their hands to some work." Lee also expressed his "willingness

that blacks should be educated, and ... that it would be better for the

blacks and for the whites." Lee forthrightly opposed allowing blacks to

vote: "My own opinion is that, at this time, they [black Southerners]

cannot vote intelligently, and that giving them the [vote] would lead

to a great deal of demagogism, and lead to embarrassments in various

ways." Lee also recommended the deportation of African Americans from Virginia and

even mentioned that Virginians would give aid in the deportation. "I

think it would be better for Virginia if she could get rid of them

[African Americans]. ... I think that everyone there would be willing

to aid it." In

an interview in May 1866, Lee said, "The Radical party are likely to do

a great deal of harm, for we wish now for good feeling to grow up

between North and South, and the President, Mr. Johnson, has been doing

much to strengthen the feeling in favor of the Union among us. The

relations between the Negroes and the whites were friendly formerly,

and would remain so if legislation be not passed in favor of the

blacks, in a way that will only do them harm." In 1868, Lee's ally Alexander H.H. Stuart drafted a public letter of endorsement for the Democratic Party's presidential campaign, in which Horatio Seymour ran against Lee's old foe Republican Ulysses S. Grant.

Lee signed it along with thirty-one other ex-Confederates. The

Democratic campaign, eager to publicize the endorsement, published the

statement widely in newspapers. Their

letter claimed paternalistic concern for the welfare of freed Southern

blacks, stating that "The idea that the Southern people are hostile to

the negroes and would oppress them, if it were in their power to do so,

is entirely unfounded. They have grown up in our midst, and we have

been accustomed from childhood to look upon them with kindness." However,

it also called for the restoration of white political rule, arguing

that "It is true that the people of the South, in common with a large

majority of the people of the North and West, are, for obvious reasons,

inflexibly opposed to any system of laws that would place the political

power of the country in the hands of the negro race. But this

opposition springs from no feeling of enmity, but from a deep-seated

conviction that, at present, the negroes have neither the intelligence

nor the other qualifications which are necessary to make them safe

depositories of political power." In

his public statements and private correspondence, however, Lee argued

that a tone of reconciliation and patience would further the interests

of white Southerners better than hotheaded antagonism to federal

authority or the use of violence. Lee repeatedly expelled white

students from Washington College for violent attacks on local black

men, and publicly urged obedience to the authorities and respect for

law and order. In 1869-70 he was a leader in successful efforts to establish state-funded schools for blacks. He privately chastised fellow ex-Confederates such as Jefferson Davis and Jubal Early for

their frequent, angry responses to perceived Northern insults, writing

in private to them as he had written to a magazine editor in 1865, that

"It should be the object of all to avoid controversy, to allay passion,

give full scope to reason and to every kindly feeling. By doing this

and encouraging our citizens to engage in the duties of life with all

their heart and mind, with a determination not to be turned aside by

thoughts of the past and fears of the future, our country will not only

be restored in material prosperity, but will be advanced in science, in

virtue and in religion." On September 28, 1870, Lee suffered a stroke that left him without the ability to speak. Lee died from the effects of pneumonia shortly after 9 a.m. on October 12, 1870, in Lexington, Virginia. He was buried underneath Lee Chapel at Washington and Lee University, where his body remains today. According to J. William Jones' Personal Reminiscences, Anecdotes, and Letters of Gen. Robert E. Lee, his last words, on the day of his death, were "Tell Hill he must come up. Strike the tent", but this is debatable because of conflicting accounts. Since Lee's stroke resulted in aphasia, last words may have been impossible.