<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Claude Adrien Helvétius, 1715

- Painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1786

- Independence Leader of the Dominican Republic Juan Pablo Duarte y Díez, 1813

PAGE SPONSOR

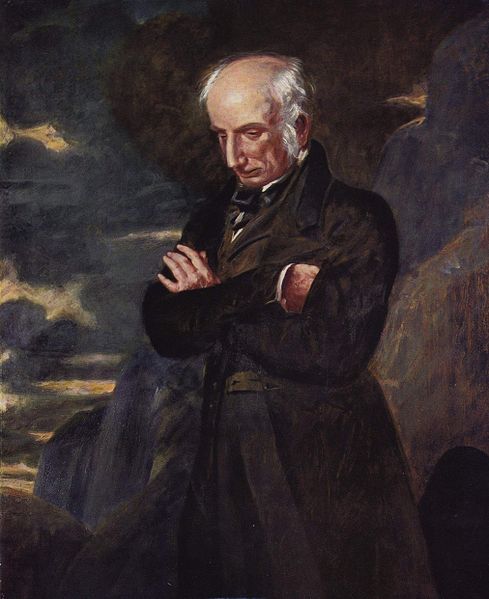

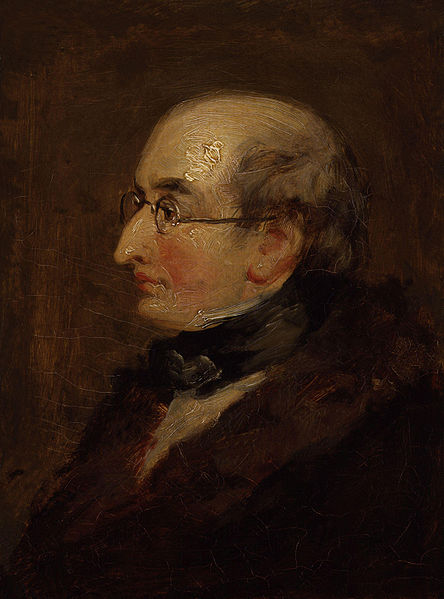

Benjamin Robert Haydon (26 January 1786 – 22 June 1846) was an English historical painter and writer.

Haydon was born at Plymouth. His mother was the daughter of the Rev. Benjamin Cobley, rector of Dodbrooke, near Kingsbridge, Devon. Her brother, General Sir Thomas Cobley, was renowned for his part in the siege of Ismail. Benjamin's father, a prosperous printer, stationer and publisher, was well known in Plymouth. Haydon, an only son, at an early date showed an aptitude for study, which was carefully fostered by his mother. At the age of six he was placed in Plymouth grammar school, and at twelve in Plympton St Mary School, the same school where Sir Joshua Reynolds had received most of his education. On the ceiling of the school-room was a sketch by Reynolds in burnt cork, which Haydon loved to sit and look at. Whilst at school he had some thought of adopting the medical profession, but he was so shocked at the sight of an operation that he gave up the idea. Reading Albinus inspired him with a love for anatomy; but from childhood he had wanted to become a painter.

Full of energy and hope, he left home, on 14 May 1804, for London, and entered the Royal Academy as a student. He was so enthusiastic that Henry Fuseli asked when he ever found time to eat. Aged twenty-one (1807) Haydon exhibited, for the first time, at the Royal Academy, The Repose in Egypt, which was bought by Thomas Hope the year after for the Egyptian Room at his townhouse in Duchess Street. This was a good start for the young artist, who shortly received a commission from Lord Mulgrave and an introduction to Sir George Beaumont. In 1809 he finished his well-known picture of Dentatus, which, though it increased his fame, resulted in a lifelong quarrel with the Royal Academy, whose committee had hung it in a small side-room instead of the great hall. That same year, he took on his first pupil, Charles Lock Eastlake, later destined to become one of the great figures of the British art establishment.

In 1810 his financial difficulties began when the allowance of £200 a year from his father was stopped. His disappointment was embittered by the controversies in which he now became involved with Beaumont, for whom he had painted his picture of Macbeth, and Richard Payne Knight, who had denied the beauties as well as the money value of the Elgin Marbles. The Judgment of Solomon, his next production, gained him £700, besides £100 voted to him by the directors of the British Institution, and the freedom of the borough of Plymouth. To restore his health and escape for a time from the cares of London life, Haydon joined his intimate friend David Wilkie in a trip to Paris; he studied at the Louvre; and on returning to England, produced Christ's Entry into Jerusalem, which afterwards formed the nucleus of the American Gallery of Painting, erected by his cousin, John Haviland of Philadelphia. Whilst painting another large work, the Resurrection of Lazarus, his financial problems increased, and he was arrested but not imprisoned, the sheriff officer taking his word for his appearance. Yet in October, 1821, he married a beautiful young widow with children, Mrs. Hyman, to whom he was devoted.

In 1823 Haydon was imprisoned in the King's Bench Prison, where he received consoling letters from leading men of the day. While there, he drew up a petition to Parliament in

favour of the appointment of "a committee to inquire into the state of

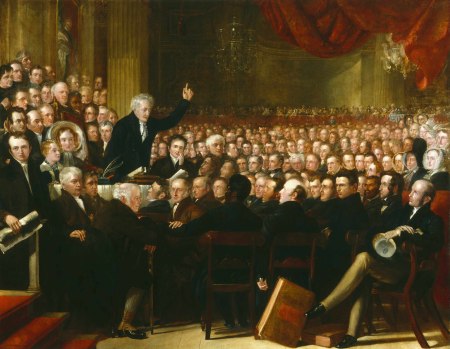

encouragement of historical painting," which was presented by Lord Brougham. During a second imprisonment in 1827, he produced the picture of the Mock Election, the idea of which had been suggested by an incident in the prison. King George IV gave him £500 for this work. Among Haydon's other pictures were: Eucles and Punch (1829); Napoleon at St Helena, for Sir Robert Peel; Xenophon, on his Retreat with the 'Ten Thousand,' first seeing the Sea; and Waiting for the Times, purchased by the Marquis of Stafford (all 1831); and Falstaff and Achilles playing the Lyre (1832). In 1834 he completed the Reform Banquet, for Lord Grey — this painting contained 597 portraits; in 1843, Curtius Leaping into the Gulf, and Uriel and Satan. There was also the Meeting of the Anti-Slavery Society, energetically treated, now in the National Portrait Gallery. When the competition took place at Westminster Hall, Haydon sent two cartoons, The Curse of Adam and Edward the Black Prince, but he was not given a prize for either. He then painted The Banishment of Aristides, which was exhibited with other productions under the same roof where the American dwarf General Tom Thumb was

making his debut in London. The exhibition was unsuccessful; and the

artist's difficulties increased to such an extent that, whilst employed

on his last grand effort, Alfred and the Trial by Jury, overcome

by debts of over £3000.0, disappointment and ingratitude, he

wrote "Stretch me no longer on this rough world," and committed suicide by

shooting himself, at sixty-one years of age. The bullet failed to kill

him; he finished the task by slitting his throat. He left a widow and

three surviving children, who were rescued from poverty by the

generosity of their father's friends; amongst the foremost of these

friends were Sir Robert Peel, Count d'Orsay, Mr. Justice Talfourd, and Lord Carlisle. Haydon was well known as a lecturer on painting and design, and from 1835 onwards visited all the principal towns in England and Scotland on lecture tours. His ambition was to see the chief buildings of Britain adorned with history paintings representing her glory. He lived to see the establishment of schools of design, and the embellishment of the new Houses of Parliament;

but in the competition of artists for the carrying out of this object,

the commissioners (including one of his former pupils) considered that

he had failed. Haydon's Lectures,

which were published shortly after their delivery, showed that he was

as bold a writer as painter. It may be mentioned in this connection

that he was the author of the long and elaborate article, "Painting,"

in the 7th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica. Haydon wrote an autobiography, which was assessed by the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition this way: Charles Dickens wrote

in 1846 that "All his life [Haydon] had utterly mistaken his vocation.

No amount of sympathy with him and sorrow for him in his manly pursuit

of a wrong idea for so many years — until, by dint of his perseverance

and courage it almost began to seem a right one — ought to prevent one

from saying that he most unquestionably was a very bad painter, and

that his pictures could not be expected to sell or to succeed." Again according to the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, "Of his three great works — Solomon, Entry into Jerusalem and Lazarus — the second is generally regarded as the finest. Solomon shows

his executive power at its loftiest, and is of itself enough to place

Haydon at the head of British historical painting in his own time. Lazarus is

a more unequal performance, and in various respects open to criticism;

yet the head of Lazarus is so majestic and impressive that, if its

author had done nothing else, we must still pronounce him a potent

pictorial genius."