<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Claude Adrien Helvétius, 1715

- Painter Benjamin Robert Haydon, 1786

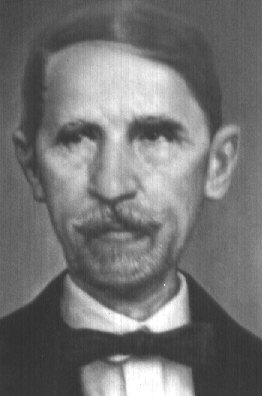

- Independence Leader of the Dominican Republic Juan Pablo Duarte y Díez, 1813

PAGE SPONSOR

Juan Pablo Duarte y Díez (January 26, 1813 – July 15, 1876) was a 19th century visionary and liberal thinker who along with Francisco del Rosario Sánchez and Matías Ramón Mella is widely considered the architect of the Dominican Republic and its independence from Haitian rule in 1844. His aspiration for the Spanish-speaking portion of the Hispaniola Island was to help create a self-sufficient nation established on the liberal ideals of a democratic government. The highest mountain in the Caribbean (Pico Duarte), a park in New York City, and many other noteworthy landmarks carry his name, suggesting the historical importance Dominicans have given to this man. His vision for the country was quickly undermined by the conservative elites, who sought to align the new nation with colonial powers and turn back to traditional regionalism. Nevertheless, his democratic ideals, although never fully fleshed-out and somewhat imprecise, have served as guiding principles, albeit mostly in theory, for most Dominican governments. His failures made him a political martyr in the eyes of subsequent generations.

Duarte was born in colonial Santo Domingo, the current capital city of Dominican Republic, during the period commonly called "The Era of Foolish Spain", or España Boba. In 1802, Duarte's future parents, Juan José Duarte and Manuela Díez Jiménez, emigrated from the Spanish colony on Hispaniola to Mayagüez, Puerto Rico. They were evading the imposition of French rule over the eastern side of the island. This transformation of the island's colonial experience became apparent when Toussaint Louverture, governor of the French colony of Saint Domingue (which occupied the western side) took control of the Spanish side as well the previous year. At the time, France and Saint Domingue were going through exhaustive social movements, namely, the French Revolution and Haitian Revolution. In occupying the Spanish side the legendary Black governor was following the indications accorded by the governments of France and Spain in the Peace of Basel signed in 1795, which had given the Spanish area to France. Upon arrival in Santo Domingo, Louverture immediately restricted slavery (however complete abolition of slavery on the eastern Hispaniola came in 1822), and in addition began converting the old Spanish colonial institutions into French Revolutionary venues of liberal government. Puerto Rico was still a Spanish colony, and Mayagüez, being so close to Hispaniola, just across the Mona Passage, had become a refuge for the like of the Duartes and those Spanish colonists who did not accept the new French rule. Most scholars assume that the Duartes’ first son, Vicente Celestino, was born here at this time on the eastern side of the Mona Passage. The family returned to Santo Domingo in 1809, however, after the War of Reconquista returned the eastern side of Hispaniola to Spanish control.

In 1821, when Duarte was eight years old, the Creole elite of Santo Domingo proclaimed its independence from Spanish rule, and renamed the former Spanish colony on Hispaniola, Spanish Haiti. The most prominent leader of the coup against the colonial government was one of its former supporters, José Núñez de Cáceres. The select and privileged group of individuals he represented were tired of being ignored by the Crown, and some were also concerned with the new liberal turn in Madrid. Their deed was not an isolated event. The 1820s was a time of profound political changes throughout the entire Spanish Atlantic World, which affected directly the lives of petite bourgeoisie like the Duartes. It began with a demoralizing conflict between Spanish royalists and liberals in the Iberian Peninsula, which is known today as the Spanish Civil War, 1820 – 1823. American patriots in arms, like Simón Bolivar in South America, immediately reaped the fruits of the metropolis’ destabilization, and began pushing back colonial troops, like what happened in the Battle of Carabobo, and then in the consequential Battle of Ayacucho. Even conservative elites in New Spain (like Agustín de Iturbide in Mexico), who had no intention of being ruled by Spanish anticlericals, moved to break ties with the crown in Spain. However, the 1821 emancipatory events in Santo Domingo were to be different from those in the continent because they did not last. Historians today call this elite’s brief courtship with sovereignty, the Ephemeral Independence. Although he was not much aware of what was going on at this time because of his young age, Juan Pablo Duarte was to look back at this affair with nostalgia, wishing that it had lasted.

The Cáceres provisional government requested support from Simón Bolivar's

new republican government, but it was ignored. Neighboring Haiti, a

former French colony that was already independent, decided to invade

the Spanish side of the island. This tactic was not new. It was meant

to keep the island out of the hands of European imperial powers and

thus a way to safeguard the Haitian Revolution. Haiti's president Jean-Pierre Boyer sent

an invasion army that took over the eastern portion of Hispaniola.

Haiti then abolished slavery there once and for all, and occupied and

absorbed Santo Domingo into the Republic of Haiti. Struggles between

Boyer and the old colonial elite helped produce a mass migration of

planters and resources. It also led to the closing of the university,

and eventually, to the elimination of the colonial elite and the

establishment of a new bourgeoisie dominant class in alignment with the

Haitian government. Following the bourgeoisie custom of sending

promising sons abroad for education, the Duartes sent Juan Pablo to the

United States and Europe in 1828. On

July 16, 1838, Duarte and others established a secret patriotic society

called La Trinitaria, which helped undermine Haitian occupation. Some

of its first members included also Juan Isidro Pérez, Pedro

Alejandro Pina, Jacinto de la Concha, Félix María Ruiz,

José María Serra, Benito González, Felipe Alfau,

and Juan Nepomuceno Ravelo. Later, he and others founded another

society, called La Filantrópica,

which had a more public presence, seeking to spread veiled ideas of

liberation through theatrical stages. All of this, along with the help

of many who wanted to be rid of the Haitians who ruled over Dominicans

led to the proclamation of independence on February 27, 1844 (Dominican War of Independence). However, Duarte had already been exiled to Caracas the

previous year for his insurgent conduct. He continued to correspond

with members of his family and members of the independence movement.

Independence could not be denied and after many struggles, the

Dominican Republic was born. A republican form of government was

established where a free people would hold ultimate power and, through

the voting process, would give rise to a democracy where every citizen

would, in theory, be equal and free. Therefore with its flag and

beautiful coat of arms, declaring "God, Fatherland and Freedom", all of

these inspired, evoked, and expressed by Duarte, came into being a

country that would soon owe this one man its existence, who gave his

fortune and the very best of his life to the cause he fervently

believed in. Duarte

was supported by many as a candidate for the presidency of the new-born

Republic. Mella wanted Duarte to simply declare himself president.

Duarte never giving up on the principles of democracy and fairness he

lived by would only accept if voted in by a majority of the Dominican

people. However the forces of those favoring Spanish sovereignty as

protection from continued Haitian threats and invasions, led by general Pedro Santana,

a large landowner from the eastern lowlands, took over and exiled

Duarte. In 1845, Santana exiled the entire Duarte family. After more

but unsuccessful Haitian invasions, internal disorder, and his and

others' misrule, Santana turned the country back into a colony of Spain

in 1861, was awarded the hereditary title of Marqués de las

Carreras by the Spanish Queen Isabella II, and died in 1864. Juan

Pablo Duarte, then living in Venezuela was made the Dominican Consul

and provided with a pension to honor him for his sacrifice. But even

this after some time was not honored and he lost commission and

pension. He, Juan Pablo Duarte, the poet, philosopher, writer, actor,

soldier, general, dreamer and hero died nobly in Caracas, Venezuela, at

the age of 63. His remains were transferred to Dominican soil in

1884 — ironically, by president and dictator Ulises Heureaux,

a man of Haitian descent — and were given a proper burial with full

honors. He is entombed in a beautiful mausoleum at the Count's Gate (La

Puerta del Conde) alongside Sanchez and Mella, who at that spot fired

the rifle shot that propelled them into legend. His birth is

commemorated by Dominicans every January 26.