<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, 1775

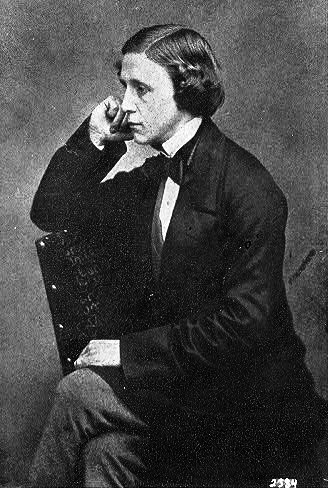

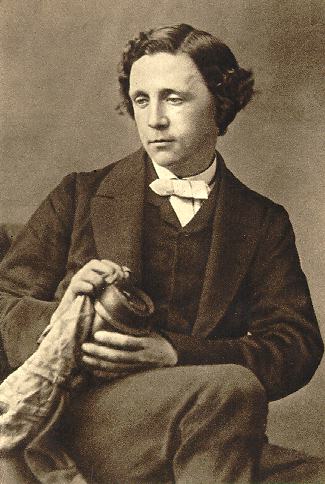

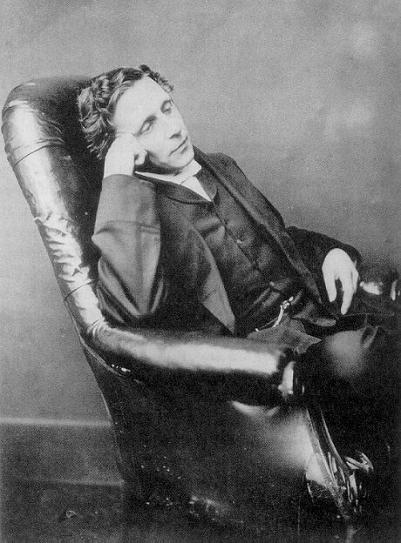

- Author Charles Ludwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), 1832

- German Emperor Wilhelm II, 1859

PAGE SPONSOR

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by the pseudonym Lewis Carroll, was an English author, mathematician, logician, Anglican deacon and a photographer. His most famous writings are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, as well as the poems "The Hunting of the Snark" and "Jabberwocky", all examples of the genre of literary nonsense. He is noted for his facility at word play, logic, and fantasy, and there are societies dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life in many parts of the world, including the United Kingdom, Japan, the United States, and New Zealand.

Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, with Irish connections. Conservative and High Church Anglican, most of Dodgson's ancestors were army officers or Church of England clergymen. His great-grandfather, also Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become a bishop. His grandfather, another Charles, had been an army captain, killed in action in 1803 when his two sons were hardly more than babies. His mother's name was Frances Jane Lutwidge. The elder of these sons — yet another Charles — was Carroll's father. He reverted to the other family business and took holy orders. He went to Rugby School, and thence to Christ Church, Oxford. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead he married his first cousin in 1827 and became a country parson. Young Charles' father was an active and highly conservative clergyman of the Anglican church who involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the Anglican church. He was High Church, inclining to Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instill such views in his children. Young Charles, however, was to develop an ambiguous relationship with his father's values and with the Anglican church as a whole.

Dodgson was born in the little parsonage of Daresbury near

Warrington, Cheshire, the eldest boy but already the third child of the

four and a half year old marriage. Eight more were to follow. When

Charles was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees in North Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious Rectory. This remained their home for the next twenty-five years. During

his early youth, young Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading

lists" preserved in the family testify to a precocious intellect: at

the age of seven the child was reading The Pilgrim's Progress. He also suffered from a stammer —

a condition shared by his siblings — that often influenced his social

life throughout his years. At twelve he was sent away to a small

private school at nearby Richmond (now part of Richmond School), where he appears to have been happy and settled. But in 1846, young Dodgson moved on to Rugby School, where he was evidently less happy, for as he wrote some years after leaving the place: Scholastically,

though, he excelled with apparent ease. "I have not had a more

promising boy his age since I came to Rugby", observed R.B. Mayor, the

Mathematics master. He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and, after an interval that remains unexplained, went on in January 1851 to Oxford, attending his father's old college, Christ Church.

He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home.

His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" — perhaps meningitis or a stroke — at the age of forty-seven. His

early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible

distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted

and so achievement came easily to him. In 1852 he received a First in Honour Moderations and was shortly thereafter nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend, Canon Edward Pusey.

However, a little later he failed an important scholarship through his

self-confessed inability to apply himself to study. Even so, his talent

as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship,

which he continued to hold for the next twenty-six years. The income

was good, but the work bored him. Many of his pupils were older and

richer than he was, and almost all of them were uninterested. However,

despite early unhappiness, Dodgson was to remain at Christ Church, in

various capacities, until his death. The

young adult Charles Dodgson was about six feet tall, slender, and

deemed attractive, with curling brown hair and blue or grey eyes

(depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat

asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly,

though this may be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age.

As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one

ear. At the age of seventeen, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough,

which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later

life. Another defect he carried into adulthood was what he referred to

as his "hesitation", a stammer he acquired in early childhood and which plagued him throughout his life. The

stammer has always been a potent part of the conceptions of Dodgson; it

is part of the belief that he stammered only in adult company and was

free and fluent with children, but there is no evidence to support this

idea. Many

children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer while many adults

failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more

acutely aware of it than most people he met; it is said he caricatured

himself as the Dodo in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland,

referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is

one of the many "facts" often-repeated, for which no firsthand evidence

remains. He did indeed refer to himself as the dodo, but that this was

a reference to his stammer is simply speculation. Although

Dodgson's stammer troubled him, it was never so debilitating that it

prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in

society. At a time when people commonly devised their own amusements

and when singing and recitation were required social skills, the young

Dodgson was well-equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He reportedly

could sing tolerably well and was not afraid to do so before an

audience. He was adept at mimicry and storytelling, and was reputedly

quite good at charades. In the interim between his early published writing and the success of the Alice books Dodgson began to move in the Pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. He developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family, and also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He also knew the fairy-tale author George MacDonald well — it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that convinced him to submit the work for publication. From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, both contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and

later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success.

Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications, The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines like the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic.

Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his

standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet

written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include

the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so some day," he wrote in July 1855. In

1856 he published his first piece of work under the name that would

make him famous. A romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in The Train under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll." This pseudonym was a play on his real name; Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which the name Charles comes. In the same year, 1856, a new Dean, Henry Liddell, arrived at Christ Church,

bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in

Dodgson's life and, over the following years, greatly influence his

writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell's wife,

Lorina, and their children, particularly the three sisters: Lorina,

Edith and Alice Liddell. He was for many years widely assumed to have

derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell. This was given some apparent substance by the fact the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking Glass spells

out her name, and that there are many superficial references to her

hidden in the text of both books. Dodgson himself, however, repeatedly

denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real

child, and

frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding

their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway's name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and no one has ever suggested this means any of the characters in the narrative are based on her. Though

information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858 – 1862 are

missing), it does seem clear that his friendship with the Liddell

family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew

into the habit of taking the children (first the boy, Harry, and later

the three girls) on rowing trips to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow. It

was on one such expedition, on 4 July 1862, that Dodgson invented the

outline of the story that eventually became his first and largest

commercial success. Having told the story and been begged by Alice

Liddell to write it down, Dodgson eventually (after much delay)

presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground in November 1864. Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read

Dodgson's incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald

children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken

the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it

immediately. After the possible alternative titles Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour were rejected, the work was finally published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier. The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. The

overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed

Dodgson's life in many ways. The fame of his alter ego "Lewis Carroll"

soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with

sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story

that Dodgson denied decades later, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice In Wonderland so

much that she suggested he dedicate his next book to her, and was

accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants. He also began earning quite substantial sums of money. However, he continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church. Late in 1871, a sequel — Through the Looking-Glass And What Alice Found There — was published. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives "1872" as the date of publication.)

Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects the changes in Dodgson's

life. His father had recently died (1868), plunging him into a

depression that lasted some years.

In 1876, Dodgson produced his last great work, The Hunting of the Snark,

a fantastical "nonsense" poem, exploring the adventures of a bizarre

crew of variously inadequate beings, and one beaver, who set off to

find the eponymous creature. The painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti reputedly became convinced the poem was about him. In

1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography, first under the

influence of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later his Oxford friend Reginald Southey. He

soon excelled at the art and became a well-known

gentleman photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea

of making a living out of it in his very early years. A recent study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over fifty

percent of his surviving work depicts young girls, though this may be a

highly distorted figure as approximately 60% of his original

photographic portfolio is now missing, so

any firm conclusions are difficult. Dodgson also made many studies of

men, women, male children and landscapes; his subjects also include

skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues and paintings, and trees. His studies

of nude children were long presumed lost, but six have since surfaced,

five of which have been published and are available online. He

also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social

circles. During the most productive part of his career, he made

portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Dodgson

abruptly ceased photography in 1880. Over 24 years, he had completely

mastered the medium, set up his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, and

created around 3,000 images. Fewer than 1,000 have survived time and

deliberate destruction. His reasons for abandoning photography remain uncertain. With the advent of Modernism, tastes changed, and his photography was forgotten from around 1920 until the 1960s. However, his literary works influenced surrealist art, including the theatre of the absurd. To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case in

1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for

inserting the then most commonly used 1d. stamp, and one each for the

other current denominations to 1s. The folder was then put into a slip

case decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and the Cheshire Cat on

the back. All could be conveniently carried in a pocket or purse. When

issued it also included a copy of Carroll's pamphletted lecture, Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing. Another invention is a writing tablet called the Nyctograph for

use at night that allowed for note-taking in the dark; thus eliminating

the trouble of getting out of bed and striking a light when one wakes

with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen

squares and system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's

design. Among

the games he devised outside of logic there are a number of word games,

including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble. He also appears to have invented, or at least certainly popularised, the Word Ladder (or

"doublet" as it was known at first); a form of brain-teaser that is

still popular today: the game of changing one word into another by

altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting

in a genuine word. For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the

following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG. Other

items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a

means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device

for a velociam (a type of tricycle); new systems of parliamentary representation; more

nearly fair elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of

postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in

betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard

scale for the college common room he worked in later in life, which,

held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price

paid; a double sided adhesive strip for things like the fastening of

envelopes or mounting things in books; a device for helping a bedridden

invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two ciphers for cryptography.

Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, matrix algebra and mathematical logic, producing nearly a dozen books. Dodgson also developed new ideas in the study of elections and committees. He worked as a mathematics tutor at Oxford, a position that enabled him some financial security. In 1895, Dodgson developed a philosophical regressus argument on deductive reasoning in his article "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles", which appeared in one of the early volumes of the philosophical journal Mind.

The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later, in

1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled Practical Tortoise Raising. Over

the remaining twenty years of his life, throughout his growing wealth

and fame, his existence remained little changed. He continued to teach

at Christ Church until 1881, and remained in residence there until his

death. His last novel, the two-volume Sylvie and Bruno, was published in 1889 and 1893 respectively. It achieved nowhere near the success of the Alice books.

Its intricacy was apparently not appreciated by the contemporary

readers, and the reviews and its sales, only 13,000 copies, were

disappointing. The only occasion on which (as far as is known) he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867, which he recounts in his "Russian Journal" which was first commercially published in 1935. He died on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts" in Guildford, of pneumonia following influenza. He was 2 weeks away from turning 66 years old. He is buried in Guildford at the Mount Cemetery.