<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, 1775

- Author Charles Ludwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), 1832

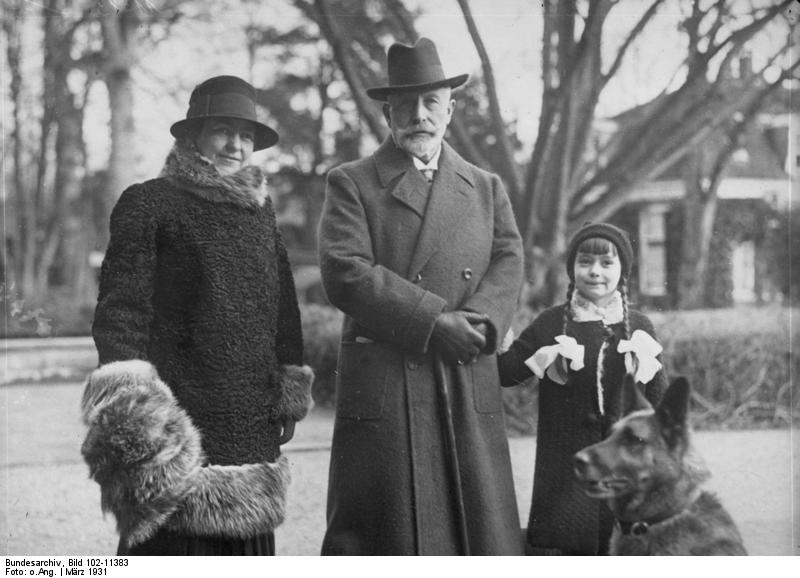

- German Emperor Wilhelm II, 1859

PAGE SPONSOR

Wilhelm II (German: Friedrich Wilhelm Victor Albert; English: Frederick William Victor Albert) (27 January 1859 – 4 June 1941) was the last German Emperor and King of Prussia, ruling both the German Empire and the Kingdom of Prussia from 15 June 1888 to 18 November 1918. (sometimes wrongly given as 9 November, the 9th was the unofficial abdication announced by Prince Max von Baden.)

Wilhelm II was born in Berlin to Frederick III, German Emperor|Prince Frederick William of Prussia (the future Frederick III) and his wife, Victoria, Princess Royal, thus making him a grandson of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom. He was Queen Victoria's first grandchild, and at the time of his birth was sixth in the British line of succession. More importantly, as the son of the Crown Prince of Prussia, Wilhelm was (from 1861) the second in the line of succession to Prussia, and also, after 1871, to the German Empire, which, according to the constitution of the German Empire, was ruled by the Prussian King. As with most Victorian era royalty, he was related to many of Europe's royal families. He was the first cousin of George V and Maud of Wales. A traumatic breech birth left him with a withered left arm due to Erb's palsy, which he tried with some success to conceal. In many photos he carries a pair of white gloves in his left hand to make the arm seem longer, or has his crippled arm on the hilt of a sword or holding a cane to give the effect of a useful limb being posed at a dignified angle. Biographers including Miranda Carter have suggested that this disability affected his emotional development. Wilhelm, beginning at age 6 was tutored by the 39-year old teacher Georg Hinzpeter. He stated later that his instructor never uttered a word of praise for his efforts. As a teenager he was educated at Kassel at the Friedrichsgymnasium and the University of Bonn, where he became a member of Corps Borussia Bonn. Wilhelm was possessed of a quick intelligence, but unfortunately this was often overshadowed by a cantankerous temper. Wilhelm took an interest in the science and technology of the age, but although he liked to pose in conversation as a man of the world, he remained convinced that he belonged to a distinct order of mankind, designated for monarchy by the grace of God. Wilhelm was accused of megalomania as early as 1892, by the Portuguese man of letters Eça de Queiroz, then in 1894 by the German pacifist Ludwig Quidde.

As a scion of the Royal house of Hohenzollern, Wilhelm was also exposed from an early age to the military society of the Prussian aristocracy. This had a major impact on him and, in maturity, Wilhelm was seldom to be seen out of uniform. The hyper-masculine military culture of Prussia in this period did much to frame Wilhelm's political ideals as well as his personal relationships. Wilhelm's relationship with the male members of his family was as interesting as that with his mother. Crown Prince Frederick was viewed by his son with a deeply felt love and respect. His father's status as a hero of the wars of unification was largely responsible for the young Wilhelm's attitude, as in the circumstances in which he was raised; close emotional contact between father and son was not encouraged. Later, as he came into contact with the Crown Prince's political opponents, Wilhelm came to adopt more ambivalent feelings toward his father, given the perceived influence of Wilhelm's mother over a figure who should have been possessed of masculine independence and strength. Wilhelm also idolised his grandfather, Wilhelm I, and he was instrumental in later attempts to foster a cult of the first German Emperor as "Wilhelm the Great".

In many ways, Wilhelm was a victim of his inheritance and of Otto von Bismarck's machinations. Both sides of his family had suffered from mental illness, and this may explain his emotional instability. The Emperor's parents, Frederick and Victoria, were great admirers of the Prince Consort of the United Kingdom, Victoria's father. They planned to rule as consorts, like Albert and Queen Victoria, and they planned to reform the fatal flaws in the executive branch that Bismarck had created for himself. The office of Chancellor responsible to the Emperor would be replaced with a British-style cabinet, with ministers responsible to the Reichstag. Government policy would be based on the consensus of the cabinet. Frederick "described the Imperial Constitution as ingeniously contrived chaos."

- "The Crown Prince and Princess shared the outlook of the Progressive Party, and Bismarck was haunted by the fear that should the old Emperor die -- and he was now in his seventies -- they would call on one of the Progressive leaders to become Chancellor. He sought to guard against such a turn by keeping the Crown Prince from a position of any influence and by using foul means as well as fair to make him unpopular."

When

Wilhelm was in his early twenties, Bismarck tried to separate him from

his liberal parents with some success. Bismarck planned to use the

young prince as a weapon against his parents in order to retain his own

political dominance. Wilhelm thus developed a dysfunctional

relationship with his parents, but especially with his English mother.

In an outburst in April 1889, which the Empress Victoria conveyed in a

letter to her mother, Queen Victoria, Wilhelm angrily implied that “an

English doctor killed my father, and an English doctor crippled my arm

– which is the fault of my mother” who allowed no German physicians to

attend to herself or her immediate family. The German Emperor Wilhelm I died in Berlin on 9 March 1888, and Prince Wilhelm's father was proclaimed Emperor as Frederick III. He was already suffering from an incurable throat cancer and

spent all 99 days of his reign fighting the disease before dying. On 15

June of that same year, his 29-year-old son succeeded him as German

Emperor and King of Prussia. Although in his youth he had been a great admirer of Otto von Bismarck,

Wilhelm's characteristic impatience soon brought him into conflict with

the "Iron Chancellor", the dominant figure in the foundation of his

empire. The new Emperor opposed Bismarck's careful foreign policy,

preferring vigorous and rapid expansion to protect Germany's "place in

the sun." Furthermore, the young Emperor had come to the throne with

the determination that he was going to rule as well as reign, unlike

his grandfather, who had largely been content to leave day-to-day

administration to Bismarck. Early

conflicts between Wilhelm II and his chancellor soon poisoned the

relationship between the two men. Bismarck believed that Wilhelm was a

lightweight who could be dominated, and he showed scant respect for

Wilhelm's policies in the late 1880s. The final split between monarch

and statesman occurred soon after an attempt by Bismarck to implement a

far-reaching anti-Socialist law in early 1890. It was during this time that Bismarck, after gaining an absolute majority in favour of his policies in the Reichstag, decided to make the anti-Socialist laws permanent. His Kartell, the majority of the amalgamated Conservative Party and the National Liberal Party,

favoured making the laws permanent, with one exception: the police

power to expel Socialist agitators from their homes. This power had

been used excessively at times against political opponents, and the

National Liberal Party was unwilling to make the expulsion clause

permanent. Bismarck would not give his assent to a modified bill, so the Kartell split

over this issue. The Conservatives would support the bill only in its

entirety, and threatened to, and eventually did, veto the entire bill.

As

the debate continued, Wilhelm became increasingly interested in social

problems, especially the treatment of mine workers who went on strike

in 1889. Following his policy of active participation in government, he

routinely interrupted Bismarck in Council to make clear where he stood

on social policy. Bismarck sharply disagreed with Wilhelm's policy and

worked to circumvent it. Even though Wilhelm supported the altered

anti-Socialist bill, Bismarck pushed for his support to veto the bill

in its entirety, but when Bismarck's arguments couldn't convince

Wilhelm, he became excited and agitated until uncharacteristically he

blurted out his motive for having the bill fail: he wanted the

Socialists to agitate until a violent clash occurred that could be used

as a pretext to crush them. Wilhelm replied that he wasn't willing to

open his reign with a bloody campaign against his subjects. The

next day, after realizing his blunder, Bismarck attempted to reach a

compromise with Wilhelm by agreeing to his social policy towards

industrial workers, and even suggested a European council to discuss working conditions, presided over by the German Emperor. Despite

this, a turn of events eventually led to his distance from Wilhelm.

Bismarck, feeling pressured and unappreciated by the Emperor and

undermined by ambitious advisors, refused to sign a proclamation

regarding the protection of workers along with Wilhelm, as was required

by the German Constitution, to protest Wilhelm's ever-increasing

interference with Bismarck's previously unquestioned authority.

Bismarck also worked behind the scenes to break the Continental labor

council Wilhelm held so dear. The final break came as Bismarck searched

for a new parliamentary majority, with his Kartell voted from power due to the anti-Socialist bill fiasco. The remaining powers in the Reichstag were the Catholic Centre Party and the Conservative Party. Bismarck wished to form a new bloc with the Centre Party, and invited Ludwig Windthorst,

the party's parliamentary leader, to discuss an alliance. This would be

Bismarck's last political maneuver. Wilhelm was furious to hear about

Windthorst's visit. In a parliamentary state, the head of government

depends on the confidence of the parliamentary majority, and certainly

has the right to form coalitions to ensure his policies a majority, but

in Germany, the Chancellor depended

on the confidence of the Emperor alone, and Wilhelm believed that the

Emperor had the right to be informed before his minister's meeting.

After a heated argument in Bismarck's estate over Imperial authority,

Wilhelm stormed out, both parting ways permanently. Bismarck, forced

for the first time into a situation he could not use to his advantage,

wrote a blistering letter of resignation, decrying Wilhelm's

interference in foreign and domestic policy, which was only published

after Bismarck's death. When Bismarck realized that his dismissal was

imminent: Although

Bismarck had sponsored landmark social security legislation, by 1889–90

he had become disillusioned with the attitude of workers. In

particular, he was opposed to wage increases, improving working

conditions, and regulating labor relations. Moreover the Kartell, the shifting political coalition that Bismarck had been able to forge

since 1867, had lost a working majority in the Reichstag. Bismarck also

attempted to sabotage the Labor Conference that the Kaiser was

organizing. In March 1890, the dismissal of Bismarck coincided with the

Kaiser's opening of the Labor Conference in Berlin. Subsequently at the opening of the Reichstag on 6 May 1890, the Kaiser stated that the most pressing issue was the further enlargement of the bill concerning the protection of the laborer. In

1891, the Reichstag passed the Workers Protection Acts, which improved

working conditions, protected women and children and regulated labor

relations. It

has been alleged that Bismarck was organizing a military coup that

would disband the striking miners, dissolve the Reichstag, repeal the

universal suffrage law, introduce limited suffrage, reduce the Kaiser

to a puppet, and establish a military dictatorship. The book that

accompanied the BBC series Fall of Eagles —

which covered the period 1848 – 1918 and traced the downfall of the

Romanov, Habsburg and Hohenzollern dynasties — contains an interview in

which Louis Ferdinand, a grandson of the Kaiser, says: Bismarck

resigned at Wilhelm II's insistence in 1890, at age 75, to be succeeded

as Chancellor of Germany and Minister-President of Prussia by Leo von Caprivi, who in turn was replaced by Chlodwig zu Hohenlohe-Schillingsfürst in 1894. In

appointing Caprivi and then Hohenlohe, Wilhelm was embarking upon what

is known to history as "the New Course", in which he hoped to exert

decisive influence in the government of the empire. There is debate

amongst historians as to the precise degree to which Wilhelm succeeded

in implementing "personal rule"

in this era, but what is clear is the very different dynamic which

existed between the Crown and its chief political servant (the

Chancellor) in the "Wilhelmine Era". These chancellors were senior

civil servants and not seasoned politician-statesmen like Bismarck.

Wilhelm wanted to preclude the emergence of another Iron Chancellor,

whom he ultimately detested as being "a boorish old killjoy" who had

not permitted any minister to see the Emperor except in his presence,

keeping a stranglehold on effective political power. Upon his enforced

retirement and until his dying day, Bismarck was to become a bitter

critic of Wilhelm's policies, but without the support of the supreme

arbiter of all political appointments (the Emperor) there was little

chance of Bismarck exerting a decisive influence on policy. Something

which Bismarck was able to effect was the creation of the "Bismarck

myth". This was a view — which some would argue was confirmed by

subsequent events — that, with the dismissal of the Iron Chancellor,

Wilhelm II effectively destroyed any chance Germany had of stable and

effective government. In this view, Wilhelm's "New Course" was

characterised far more as the German ship of state going out of

control, eventually leading through a series of crises to the carnage

of the First and Second World Wars. Following the dismissal of Hohenlohe in 1900, Wilhelm appointed the man whom he regarded as "his own Bismarck", Bernhard von Bülow.

Wilhelm hoped that in Bülow, he had found a man who would combine

the ability of the Iron Chancellor with the respect for Wilhelm's

wishes which would allow the empire to be governed as he saw fit.

Wilhelm's

involvement in the domestic sphere was more limited in the early

twentieth century than it had been in the first years of his reign. In

part, this was due to the appointment of Bülow and Bethmann —

arguably both men of greater force of character than Wilhelm's

earlier chancellors — but also because of his increasing interest in

foreign affairs. German

foreign policy under Wilhelm II was faced with a number of significant

problems. Perhaps the most apparent was that Wilhelm was an impatient

man, subjective in his reactions and affected strongly by sentiment and

impulse. He was personally ill-equipped to steer German foreign policy

along a rational course. It is now widely recognized that the various

spectacular acts which Wilhelm undertook in the international sphere

were often partially encouraged by the German foreign policy elite. There were a number of key exceptions, such as the famous Kruger telegram of 1896 in which Wilhelm congratulated President Paul Kruger of the Transvaal Republic on the suppression of the Jameson Raid, thus alienating British public opinion. After the murder of the German ambassador during the Boxer Rebellion in 1900, a regiment of German troops was sent to China. In a speech of 27 July 1900, the Emperor exhorted these troops: Though its full impact was not felt until many years later, when Entente and

American propagandists took advantage from this careless public speech,

this is another example of his unfortunate propensity for impolitic

public utterances. This weakness made him vulnerable to manipulation by

interests within the German foreign policy elite, as subsequent events

were to prove. Wilhelm had much disdain for his uncle, King Edward VII of the United Kingdom, who was much more popular as a sovereign in Europe. One of the few times Wilhelm succeeded in personal "diplomacy" was when with he supported Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria in marrying Sophie Chotek in 1900 against the wishes of Emperor Franz Joseph. Deeply in love, Franz Ferdinand refused to consider marrying anyone else. Pope Leo XIII, Tsar Nicholas II of Russia,

and Wilhelm all made representations on Franz Ferdinand's behalf to the

Emperor Franz Joseph, arguing that the disagreement between Franz

Joseph and Franz Ferdinand was undermining the stability of the

monarchy. One "domestic" triumph for Wilhelm was when his daughter Victoria Louise married the Duke of Brunswick in 1913; this helped heal the rift between the House of Hanover and the House of Hohenzollern after the 1866 annexation of Hanover by Prussia. In 1914, Wilhelm's son Prince Adalbert of Prussia married a Princess of the Ducal House of Saxe-Meiningen. However the rifts between the House of Hohenzollern and the two leading Royal dynasties of Europe — the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and House of Romanov — would only get worse. Following his dismissal of Bismarck, Wilhelm and his new chancellor Caprivi became aware of the existence of the secret Reinsurance Treaty with

the Russian Empire, which Bismarck had concluded in 1887. Wilhelm's

refusal to renew this agreement which guaranteed Russian neutrality in

the event of an attack by France was seen by many historians as the

worst offense committed by Wilhelm in terms of foreign policy. In

reality, the decision to allow the lapse of the treaty was largely the

responsibility of Caprivi, though Wilhelm supported his chancellor's

actions. It is important not to overestimate the influence of the

Emperor in matters of foreign policy after the dismissal of Bismarck,

but it is certain that his erratic meddling contributed to the general

lack of coherence and consistency in the policy of the German Empire

toward other powers. In

December 1897, Wilhelm visited Bismarck for the last time. On many

occasions, Bismarck had expressed grave concerns about the dangers of

improvising government policy based on the intrigues of courtiers and

militarists. Bismarck’s last warning to Wilhelm was: Your

Majesty, so long as you have this present officer corps, you can do as

you please. But when this is no longer the case, it will be very

different for you. Subsequently, just before he died, Bismarck made these dire and accurate predictions: Jena twenty years after the death of Frederick the Great; the crash will come twenty years after my departure if things go on like this" ― a prophecy fulfilled almost to the month. One day the great European War will come out of some damned foolish thing in the Balkans. Bismarck

had warned in February 1888 of a Balkan crisis turning into a world war

(although when that war did come in 1914, the Balkan country was Serbia, not Bulgaria): He

warned of the imminent possibility that Germany will have to fight on

two fronts; he spoke of the desire for peace; then he set forth the

Balkan case for war and demonstrates its futility: "Bulgaria, that

little country between the Danube and the Balkans, is far from being an

object of adequate importance... for which to plunge Europe from Moscow

to the Pyrenees, and from the North Sea to Palermo, into a war whose

issue no man can foresee. At the end of the conflict we should scarcely

know why we had fought." A

typical example of this was his "love-hate" relationship with the

United Kingdom and in particular with his British cousins. He returned

to England in January 1901 to be at the bedside of his grandmother, Queen Victoria, and was holding her in his arms at the moment of her death. Open

armed conflict with Britain was never what Wilhelm had in mind — "a most

unimaginable thing", as he once quipped — yet he often gave in to the

generally anti-British sentiments within the upper echelons of the

German government, conforming as they did to his own prejudices toward

Britain which arose from his youth. When war came about in 1914,

Wilhelm sincerely believed that he was the victim of a diplomatic

conspiracy set up by his late uncle, Edward VII, in which Britain had actively sought to "encircle" Germany through the conclusion of the Entente Cordiale with

France in 1904 and a similar arrangement with Russia in 1907. This is

indicative of the fact that Wilhelm had a highly unrealistic belief in

the importance of "personal diplomacy" between European monarchs, and

could not comprehend that the very different constitutional position of

his British cousins made this largely irrelevant. A reading of the Entente Cordiale shows that it was actually an attempt to put aside the ancient rivalries between France and Great Britain rather than an "encirclement" of Germany. Similarly, he believed that his personal relationship with his cousin-in-law Nicholas II of Russia (The Willy-Nicky Correspondence) was sufficient to prevent war between the two powers. At a private meeting at Björkö in

1905, Wilhelm concluded an agreement with his cousin which amounted to

a treaty of alliance, without first consulting with Bülow. A

similar situation confronted Czar Nicholas on his return to St.

Petersburg, and the treaty was, as a result, a dead letter. But Wilhelm

believed that Bülow had betrayed him, and this contributed to the

growing sense of dissatisfaction he felt towards the man he hoped would

be his foremost servant. In broadly similar terms to the "personal

diplomacy" at Björkö,

his attempts to avoid war with Russia by an exchange of telegrams with

Nicholas II in the last days before the outbreak of the First World War

came unstuck due to the reality of European power politics. His

attempts to woo Russia were also seriously out of step with existing

German commitments to Austria-Hungary. In a chivalrous fidelity to the Austro-Hungarian/German alliance, Wilhelm informed the Emperor Franz Joseph I of Austria in

1889 that "the day of Austro-Hungarian mobilisation, for whatever

cause, will be the day of German mobilisation too". Given that Austrian

mobilisation for war would most likely be against Russia, a policy of

alliance with both powers was obviously impossible. Wilhelm

additionally believed in inferiority of Slavs and is known to have said

in 1913 that "The Slavs were not born to rule but to serve, this they

must be taught". In

some cases, Wilhelm II's diplomatic "blunders" were often part of a

wider reaching policy emanating from the German governing élite.

One such action sparked the Moroccan Crisis of 1905, when Wilhelm was persuaded (largely against his wishes) to make a spectacular visit to Tangier, in Morocco. Wilhelm's presence was seen as an assertion of German interests in Morocco and in a speech he even made certain remarks in favour of Moroccan independence. This led to friction with France, which had expanding colonial interests in Morocco, and led to the Algeciras Conference, which served largely to further isolate Germany in Europe. Britain

and France's alliance fortified as a corollary, mainly due to the fact

that Britain advocated France's endeavors to colonise Morocco, whereas

Wilhelm supported Moroccan self-determination: and so, the German

Emperor became even more resentful. Perhaps

Wilhelm's most damaging personal blunder in the arena of foreign policy

had a far greater impact in Germany than internationally. The Daily Telegraph Affair

of 1908 stemmed from the publication of some of Wilhelm's opinions in

edited form in the British daily newspaper of that name. Wilhelm saw it

as an opportunity to promote his views and ideas on Anglo-German

friendship, but instead, due to his emotional outbursts during the

course of the interview, Wilhelm ended up further alienating not only

the British people, but also the French, Russians, and Japanese all in

one fell swoop by implying, inter alia, that the Germans cared

nothing for the British; that the French and Russians had attempted to

incite Germany to intervene in the Second Boer War;

and that the German naval buildup was targeted against the Japanese,

not Britain. (One memorable quote from the interview is "You English

are mad, mad, mad as March hares.")

The effect in Germany was quite significant, with serious calls for his

abdication being mentioned in the press. Quite understandably, Wilhelm

kept a very low profile for many months after the Daily Telegraph fiasco,

and later exacted his revenge by enforcing the resignation of Prince

Bülow, who had abandoned the Emperor to public criticism by

publicly accepting some responsibility for not having edited the

transcript of the interview before its publication. The Daily Telegraph crisis deeply wounded Wilhelm's previously unimpaired self-confidence, so much so that he soon suffered a severe bout of depression from

which he never really recovered (photographs of Wilhelm in the

post-1908 period show a man with far more haggard features and greying

hair), and he lost much of the influence he had previously exercised in

domestic and foreign policy. Nothing

Wilhelm II did in the international arena was of more influence than

his decision to pursue a policy of massive naval construction. A

powerful navy was Wilhelm's pet project. He had inherited, from his

mother, a love of the British Royal Navy, which was at that time the world's largest. He once confided to his uncle, Edward VII, that his dream was to have a "fleet of my own some day". Wilhelm's frustration over his fleet's poor showing at the Fleet Review at his grandmother Queen Victoria's Diamond Jubilee celebrations, combined with his inability to exert German influence in South Africa

following the dispatch of the Kruger telegram, led to Wilhelm taking

definitive steps toward the construction of a fleet to rival that of

his British cousins. Wilhelm was fortunate to be able to call on the

services of the dynamic naval officer Alfred von Tirpitz,

whom he appointed to the head of the Imperial Naval Office in 1897. The

new admiral had conceived of what came to be known as the "Risk Theory"

or the Tirpitz Plan,

by which Germany could force Britain to accede to German demands in the

international arena through the threat posed by a powerful battlefleet

concentrated in the North Sea. Tirpitz enjoyed

Wilhelm's full support in his advocacy of successive naval bills of

1897 and 1900, by which the German navy was built up to contend with

that of the United Kingdom. Naval expansion under the Fleet Acts eventually

led to severe financial strains in Germany by 1914, as by 1906 Wilhelm

had committed his navy to construction of the much larger, more

expensive dreadnought type of battleship. In 1889 Wilhelm II reorganised top level control of the navy by creating a Navy Cabinet (Marine-Kabinett) equivalent to the German Imperial Military Cabinet which

had previously functioned in the same capacity for both the army and

navy. The Head of the navy cabinet was responsible for promotions,

appointments, administration and issuing orders to naval forces. Captain Gustav von Senden-Bibran was appointed as its first head and remained so until 1906. The existing

Imperial admiralty was abolished and its responsibilities divided

between two organisations. A new position (equivalent to the supreme

commander of the army) was created, chief of the high command of the

admiralty (Oberkommando der Marine), being responsible for ship deployments, strategy and tactics. Vice Admiral Max von der Goltz was

appointed in 1889 and remained in post until 1895. Construction and

maintenance of ships and obtaining supplies was the responsibility of

the State Secretary of the Imperial Navy Office (Reichsmarineamt), responsible to the Chancellor and advising the Reichstag on naval matters. The first appointee was Rear Admiral Eduard Heusner, followed shortly by Rear Admiral Friedrich von Hollmann from 1890 to 1897. Each of these three heads of department reported separately to Wilhelm II. In addition to the expansion of the fleet the Kiel Canal was opened in 1895 enabling faster movements between the North Sea and the Baltic Sea. Wilhelm was a friend of Franz Ferdinand, Archduke of Austria-Este, and he was deeply shocked by his assassination on 28 June 1914. Wilhelm offered to support Austria-Hungary in crushing the Black Hand,

the secret organization that had plotted the killing, and even

sanctioned the use of force by Austria against the perceived source of

the movement — Serbia (this

is often called "the blank cheque"). He wanted to remain in Berlin

until the crisis was resolved, but his courtiers persuaded him instead

to go on his annual cruise of the North Sea on 6 July 1914. It was

perhaps realized that Wilhelm's presence would be more of a hindrance

to those elements in the government who

wished to use the crisis to increase German prestige, even at the risk

of general war — something of which Wilhelm, for all his bluster, was

extremely apprehensive. Wilhelm made erratic attempts to stay on top of the crisis via telegram, and when the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum was

delivered to Serbia, he hurried back to Berlin. He reached Berlin on 28

July, read a copy of the Serbian reply, and wrote on it: A

brilliant solution — and in barely 48 hours! This is more than could have

been expected. A great moral victory for Vienna; but with it every

pretext for war falls to the ground, and [the Ambassador] Giesl had

better have stayed quietly at Belgrade. On this document, I should

never have given orders for mobilization. Unknown to the Emperor, Austro-Hungarian ministers and generals had already convinced the 84-year-old Francis Joseph I of Austria to sign a declaration of war against Serbia. As a direct consequence, Russia began a general mobilization to attack Austria in defense of Serbia. On

the night of July 30 when handed a document stating that Russia would

not cancel its mobilization, Wilhelm wrote a lengthy commentary containing the startling observations: When

it became clear that the United Kingdom would enter the war if Germany

attacked France through neutral Belgium, the panic-stricken Wilhelm

attempted to redirect the main attack against Russia. When Helmuth von Moltke (the younger) told him that this was impossible, Wilhelm said: "Your uncle would have given me a different answer!" Wilhelm is also reported to have said: "To think that George and Nicky should have played me false! If my grandmother had been alive, she would never have allowed it." Wilhelm is a controversial issue in historical scholarship and this period of German history.

Until the late 1950s he was seen as an important figure in German

history during this period. For many years after that, the dominant

view was that he had little or no influence on German policy, a view which has been challenged since the late 1970s, particularly by Professor John C.G. Röhl, who saw Wilhelm II as the key figure in understanding the recklessness and downfall of Imperial Germany. It is difficult to argue that Wilhelm actively sought to unleash the First World War.

Though he had ambitions for the German Empire to be a world power, it

was never Wilhelm's intention to conjure a large-scale conflict to

achieve such ends. As soon as his better judgment dictated that a world

war was imminent, he made strenuous efforts to preserve the peace — such

as The Willy-Nicky Correspondence mentioned

earlier, and his optimistic interpretation of the Austro-Hungarian

ultimatum that Austro-Hungarian troops should go no further than Belgrade,

thus limiting the conflict. But by then it was far too late, for the

eager military officials of Germany and the German Foreign Office were

successful in persuading him to sign the mobilisation order and

initiate the Schlieffen Plan that envisioned the occupation of Paris within

40 days. The contemporary British reference to the First World War as

"the Kaiser's War" in the same way that the Second was "Hitler's War"

is not wholly accurate in its suggestion that Wilhelm was deliberately

responsible for unleashing the conflict. "He may not have been 'the

father of war' but he was certainly its godfather'. According to the the book, All Quiet on the Western Front, Remarque talks about the Kaiser's visit to the western front and how unimpressed he was by his height and speech. His own love of the culture and trappings of militarism and push to endorse the German military establishment and industry (most notably the Krupp corporation),

which were the key support which enabled his dynasty to rule helped

push his empire into an armaments race with competing European powers.

Similarly, though on signing the mobilisation order, Wilhelm is

reported as having said, "You will regret this, gentlemen." He had

encouraged Austria to pursue a hard line with Serbia, was an

enthusiastic supporter of the subsequent German actions during the war,

and reveled in the title of "Supreme War Lord" and "Allerhöchste"

(All-highest). Germany's war aims were

published with his consent on 9 September 1914, and stiffened his

enemies' resolve to avoid a compromise peace, whatever the costs. The

role of ultimate arbiter of wartime national affairs proved too heavy a

burden for Wilhelm. Even the advice of his closest aides such as Moriz von Lyncker was

not adequate. As the war progressed, his influence receded and

inevitably his lack of ability in military matters led to an

ever-increasing reliance upon his generals, so much that after 1916 the

Empire had effectively become a military dictatorship under the control

of Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. Increasingly

cut off from reality and the political decision-making process, Wilhelm

vacillated between defeatism and dreams of victory, depending upon the

fortunes of his armies. He remained a useful figurehead, and he toured

the lines and munitions plants, awarded medals and gave encouraging speeches. In

December 1916, the Germans attempted to negotiate peace with the

Allies, declaring themselves the victors. The negotiations were

mediated by the United States, but the Allies rejected the offer. A

German poster from January 1917 quotes a speech by Kaiser Wilhelm II

lambasting the Allies for their decision. Nevertheless,

Wilhelm still retained the ultimate authority in matters of political

appointment, and it was only after his consent had been gained that

major changes to the high command could be effected. Wilhelm was in

favour of the dismissal of Helmuth von Moltke the Younger in September 1914 and his replacement by Erich von Falkenhayn. Similarly, Wilhelm was instrumental in the policy of inactivity adopted by the High Seas Fleet after the Battle of Jutland in

1916. Likewise, it was largely owing to his sense of having been pushed

into the shadows that Wilhelm attempted to take a leading role in the

crisis of 1918. In the end, he realized the necessity of capitulation and insisted that the German nation should not bleed to death for a dying cause. Upon hearing that his cousin George V had changed the name of the British royal house to Windsor, Wilhelm remarked that he planned to see Shakespeare's play The Merry Wives of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

Following the 1917 February Revolution in Russia which saw the overthrow of Great War adversary Emperor Nicholas II, Wilhelm arranged for the exiled Russian Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin to

return home from Switzerland via Germany, Sweden and Finland. Wilhelm

hoped that Lenin would create political unrest back in Russia, which

would help to end the war on the Eastern front, allowing Germany to

concentrate on defeating the Western allies. The Swiss communist Fritz Platten managed to negotiate with the German government for Lenin and his company to travel through Germany by rail, on the so-called "sealed train". Lenin arrived in Petrograd on 16 April 1917, and seized power seven months later in the October Revolution. Wilhelm's strategy paid off when Russia signed the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk on 3 March 1918, withdrawing from the war and ceding Finland. On Lenin's orders, Nicholas II, Wilhelm's first cousin; Empress Alexandra; their five children; and their few servants were murdered by a Bolshevik firing squad in Yekaterinburg on 17 July 1918. Wilhelm was at the Imperial Army headquarters in Spa, Belgium, when the uprisings in Berlin and other centres took him by surprise in late 1918. Mutiny among the ranks of his beloved Kaiserliche Marine, the imperial navy, profoundly shocked him. After the outbreak of the German Revolution,

Wilhelm could not make up his mind whether or not to abdicate. Up to

that point, he was confident that even if he were obliged to vacate the

German throne, he would still retain the Prussian kingship. The

unreality of this belief was revealed when, for the sake of preserving

some form of government in the face of anarchy, Wilhelm's abdication

both as German Emperor and King of Prussia was abruptly announced by

the Chancellor, Prince Max of Baden, on 9 November 1918. (Prince Max himself was forced to resign later the same day, when it became clear that only Friedrich Ebert, leader of the SPD could effectively exert control.) Wilhelm consented to the abdication only after Ludendorff's replacement, General Wilhelm Groener, had informed him that the officers and men of the army would march back in good order under Paul von Hindenburg's

command, but would certainly not fight for Wilhelm's throne on the home

front. The monarchy's last and strongest support had been broken, and

finally even Hindenburg, himself a lifelong royalist,

was obliged, with some embarrassment, to advise the Emperor to give up

the crown. For telling Wilhelm the truth, Groener would not be forgiven

by German arch-conservatives. The abdication instrument was not

actually signed until 28 November; by then his six sons had sworn not

to succeed him, so ending the dynasty's connection with the crown of

Prussia.

The following day, the now-former German Emperor Wilhelm II crossed the border by train and went into exile in the Netherlands, which had remained neutral throughout the war. Upon the conclusion of the Treaty of Versailles in

early 1919, Article 227 expressly provided for the prosecution of

Wilhelm "for a supreme offence against international morality and the

sanctity of treaties", but Queen Wilhelmina refused to extradite him, despite appeals from the Allies. The erstwhile Emperor first settled in Amerongen, and then subsequently purchased a small castle in the municipality of Doorn on 16 August 1919 and moved in on 15 May 1920. This was to be his home for the remainder of his life. From this residence, Huis Doorn,

Wilhelm absolved his officers and servants of their oath of loyalty to

him; however, he himself never formally relinquished his titles, and

hoped to return to Germany in the future. The Weimar Republic allowed

Wilhelm to remove twenty-three railway wagons of furniture,

twenty-seven containing packages of all sorts, one bearing a car and

another a boat, from the New Palace at Potsdam. The telegrams that were exchanged between the General Headquarters of the Imperial High Command, Berlin, and President Woodrow Wilson are discussed in Ferdinand Czernin's Versailles, 1919. The following telegram was sent through the Swiss government and arrived in Washington, D.C., on 5 October 1918: In

order to avoid further bloodshed the German Government requests to

bring about the immediate conclusion of an armistice on land, on water,

and in the air. In

the subsequent two exchanges, Wilson's allusions "failed to convey the

idea that the Kaiser's abdication was an essential condition for peace.

The leading statesmen of the Reich were not yet ready to contemplate

such a monstrous possibility." The third German telegram was sent on 20

October. Wilson's reply on 23 October contained the following: According to Czernin: Wilhelm's

abdication was necessitated by the popular perceptions that had been

created by the Entente propaganda against him, which had been picked and further refined when the U.S. declared war in April 1917. A

much bigger obstacle, which contributed to the five-week delay in the

signing of the armistice and to the resulting social deterioration in

Europe, was the fact that the Entente Powers had no desire to accept the Fourteen Points and Wilson's subsequent promises. As Czernin points out: The Kaiser himself wrote: On 2 December 1919, Wilhelm wrote to Field Marshal August von Mackensen,

denouncing his abdication as the "deepest, most disgusting shame ever

perpetrated by a person in history, the Germans have done to

themselves", "egged on and misled by the tribe of Judah ... Let no German ever forget this, nor rest until these parasites have been destroyed and exterminated from German soil!" He advocated a "regular international all-worlds pogrom à la Russe" as "the best cure" and further believed that Jews were a "nuisance that humanity must get rid of some way or other. I believe the best would be gas!" In

1922, Wilhelm published the first volume of his memoirs — a very slim

volume which nevertheless revealed the possession of a remarkable

memory (Wilhelm had no archive on which to draw). In them, he asserted

his claim that he was not guilty of initiating the Great War, and

defended his conduct throughout his reign, especially in matters of

foreign policy. For the remaining twenty years of his life, the aging

Emperor regularly entertained guests (often of some standing) and kept

himself updated on events in Europe. On his arrival from Germany at Amerongen Castle

in the Netherlands in 1918, the first thing Wilhelm said to his host

was, "So what do you say, now give me a nice cup of hot, good, real

English tea." No

longer able to call upon the services of a court barber, and partly out

of a desire to disguise his features, Wilhelm grew a beard and allowed

his famous moustache to droop. Wilhelm even learned the Dutch language. Wilhelm developed a penchant for archaeology during his vacations on Corfu, a passion he retained in his exile. He had bought the former Greek residence of Austrian Empress Elisabeth after

her murder in 1898. He also sketched plans for grand buildings and

battleships when he was bored, although experts in construction saw his

ideas as grandiose and unworkable. One of Wilhelm's greatest passions

was hunting, and he bagged thousands of animals, both beast and bird.

Much of his time was spent chopping wood (a hobby he discovered upon

his arrival at Doorn) and observing the life of a country gentleman. During his years in Doorn, he largely deforested his estate, the land only now beginning to recover. In the early 1930s, Wilhelm apparently hoped that the successes of the German Nazi Party would

stimulate interest in the revival of the monarchy. His second wife,

Hermine, actively petitioned the Nazi government on her

husband's behalf, but the scorn which Adolf Hitler felt for the man who he believed contributed to Germany's greatest defeat,

and his own desire for power would prevent Wilhelm's restoration. Though he hosted Hermann Göring at Doorn on at least one occasion, Wilhelm grew to mistrust Hitler. He heard about the Night of the Long Knives of 30 June 1934 by wireless and said of it, "What would people have said if I had done such a thing?" and hearing of the murder of the wife of former Chancellor Schleicher,

"We have ceased to live under the rule of law and everyone must be

prepared for the possibility that the Nazis will push their way in and

put them up against the wall!" Wilhelm was also appalled at the Kristallnacht of 9–10 November 1938 saying, "I have just made my views clear to Auwi [Wilhelm's

fourth son] in the presence of his brothers. He had the nerve to say

that he agreed with the Jewish pogroms and understood why they had come

about. When I told him that any decent man would describe these actions

as gangsterisms, he appeared totally indifferent. He is completely lost

to our family ..." In the wake of the German victory over Poland in

September 1939, Wilhelm's adjutant, General von Dommes, wrote on his

behalf to Hitler, stating that the House of Hohenzollern "remained

loyal" and noted that nine Prussian Princes (one son and eight

grandchildren) were stationed at the front, concluding "because of the

special circumstances that require residence in a neutral foreign

country, His Majesty must personally decline to make the aforementioned

comment. The Emperor has therefore charged me with making a

communication." Wilhelm stayed in regular contact with Hitler through

General von Dommes, who represented the family in Germany. Wilhelm greatly admired the success which Hitler was able to achieve in the opening months of the Second World War,

and personally sent a congratulatory telegram on the fall of Paris

stating "Congratulations, you have won using my troops." Nevertheless,

after the Nazi conquest of the Netherlands in 1940, the aging Wilhelm

retired completely from public life. During

his last year at Doorn, Wilhelm believed that Germany was the land of

monarchy and therefore of Christ and that England was the land of Liberalism and therefore of Satan and the Anti-Christ. He argued that the English ruling classes were "Freemasons thoroughly infected by Juda". Wilhelm asserted that the "British people must be liberated from Antichrist Juda. We must drive Juda out of England just as he has been chased out of the Continent." He

believed the Freemasons and Jews had caused the two world wars, aiming

at a world Jewish empire with British and American gold, but that

"Juda's plan has been smashed to pieces and they themselves swept out

of the European Continent!" Continental Europe was now, Wilhelm wrote,

"consolidating and closing itself off from British influences after the

elimination of the British and the Jews!" The end result would be a "U.S. of Europe!" In a letter to his sister Princess Margaret in

1940, Wilhelm wrote: "The hand of God is creating a new world &

working miracles ... We are becoming the U.S. of Europe under German

leadership, a united European Continent." He added: "The Jews [are]

being thrust out of their nefarious positions in all countries, whom

they have driven to hostility for centuries." Also

in 1940 came what would have been his mother's 100th birthday, of which

he ironically wrote to a friend "Today the 100th birthday of my mother!

No notice is taken of it at home! No 'Memorial Service' or... committee

to remember her marvellous work for the...welfare of our German

people... Nobody of the new generation knows anything about her." The

entry of the German army into Paris stirred painful, deep-seated

emotions within him. In a letter to his daughter Victoria Louise, the

Duchess of Brunswick, he wrote: Thus is the pernicious entente cordial of Uncle Edward VII brought to nought. Concerning Hitler's persecutions of the Jews: The Jewish persecutions of 1938 horrified the exile. "For the first time, I am ashamed to be a German." Given

that such comment directly contradicts his praise of Jews being removed

from their occupations and residences in Europe (cited above), it is

unclear which of the two positions (if either) is Wilhelm's true one. Wilhelm II died of a pulmonary embolus in

Doorn, Netherlands on 4 June 1941 aged 82, with German soldiers at the

gates of his estate. Hitler, however, was reportedly angry that the

former monarch had an honour guard of German troops and nearly fired

the general who ordered them there when he found out. Despite his

personal animosity toward Wilhelm, Hitler hoped to bring Wilhelm's body

back to Berlin for a state funeral, as Wilhelm was a symbol of Germany

and Germans during World War I. Hitler felt this would demonstrate to Germans the direct succession of the Third Reich from the old Kaiserreich. However,

Wilhelm's wishes of never returning to Germany until the restoration of

the monarchy were respected, and the Nazi occupation authorities

granted a small military funeral with a few hundred people present, the

mourners including August von Mackensen, along with a few other military advisors. Wilhelm's request that the swastika and

other Nazi regalia not be displayed at the final rites was ignored,

however, and they feature in the photos of the funeral that were taken

by a Dutch photographer. He

was buried in a mausoleum in the grounds of Huis Doorn, which has since

become a place of pilgrimage for German monarchists. To this day, small

but enthusiastic numbers of them gather at Huis Doorn every year on the

anniversary of his death to pay their homage to the last German Emperor.