<Back to Index>

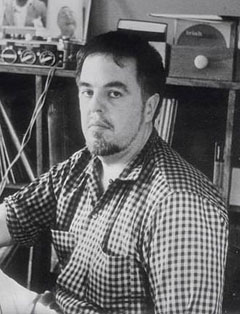

- Musicologist Alan Lomax, 1915

- Composer Franz Peter Schubert, 1797

- President of the Federal Republic of Germany Theodor Heuss, 1884

PAGE SPONSOR

Alan Lomax (January 31, 1915 – July 19, 2002) was an American folklorist and ethnomusicologist. He was one of the great field collectors of folk music of the 20th century, recording thousands of songs in the United States, Great Britain, Ireland, the Caribbean, Italy, and Spain.

Lomax was the son of pioneering folklorist and author John A. Lomax, with whom he started his career by recording songs sung by sharecroppers and prisoners in Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. Because of frail health he was mostly home schooled, but attended The Choate School (now Choate Rosemary Hall) for a year, graduating in 1930 at age 15. He enrolled at the University of Texas at Austin in 1930 and the following year studied philosophy at Harvard but upon his mother's death interrupted his education to console his father and join him on his folk song collecting field trips. He subsequently earned a degree in philosophy from the University of Texas and later did graduate studies with Melville J. Herskovits at Columbia University and with Ray Birdwhistell at the University of Pennsylvania. To some, he is best known for his theories of Cantometrics, Choreometrics, and Parlametrics, elaborated from 1960 until his death with the help of collaborators Victor Grauer, Conrad Arensberg, Forrestine Paulay, and Roswell Rudd.

From 1937 to 1942, Lomax was Assistant in Charge of the Archive of Folk Song of the Library of Congress to which he and his father and numerous collaborators contributed more than ten thousand field recordings. During his lifetime, he collected folk music from the United States, Haiti, the Caribbean, Ireland, Great Britain, Spain, and Italy, assembling a treasure trove of American and international culture. A pioneering oral historian, he also recorded substantial interviews with many legendary folk musicians, including Woody Guthrie, Lead Belly, Muddy Waters, Jelly Roll Morton, Irish singer Margaret Barry, Scots ballad singer Jeannie Robertson, and Harry Cox of Norfolk, England, among many others. After the bombing of Pearl Harbor he took his recording machine into the streets to capture the reactions of everyday citizens. While serving in the army in World War II he made numerous radio programs in connection with the war effort. The 1944 "ballad opera," The Martins and the Coys, broadcast in Britain (but not the USA) by the BBC, featuring Burl Ives, Woody Guthrie, Will Geer, Sonny Terry, Pete Seeger, and Fiddlin' Arthur Smith, among others, was released on Rounder Records in 2000.

He also produced recordings, concerts, and radio shows, in the U.S and in England, which played an important role in both the American and British folk revivals of the 1940s, '50s and early '60s. In the late 1940s, he produced a highly regarded series of folk music albums for Decca records and organized a series of concerts at New York's Town Hall and Carnegie Hall, featuring blues, Calypso, and Flamenco music. He also hosted a radio show, Your Ballad Man, from 1945-49 that was broadcast nationwide on the Mutual Radio Network and featured a highly eclectic program, from gamelan music, to Django Reinhardt, to Klezmer music, to Sidney Bechet and Wild Bill Davison, to jazzy pop songs by Maxine Sullivan and Jo Stafford, to readings of the poetry of Carl Sandburg, to hillbilly music with electric guitars, to Finnish brass bands – to name a few.

Lomax spent the 1950s based in London, from where he edited the 18-volume Columbia World Library of Folk and Primitive Music, an anthology issued on newly invented LP records. For the British and Irish volumes, he worked with the BBC and folklorists Peter Douglas Kennedy, Scots poet Hamish Henderson, and with Séamus Ennis in Ireland, where they recorded Irish traditional musicians, including some of the songs in English and Irish of Elizabeth Cronin in 1951. He also hosted a folk music show on BBC's home service and organized a skiffle group, Alan Lomax and the Ramblers (who included Ewan MacColl, Peggy Seeger, and Shirley Collins, among others) which appeared on British television. His ballad opera Big Rock Candy Mountain premiered December 1955 at Joan Littlewood's Theater Workshop and featured Ramblin' Jack Elliot.

Lomax and Diego Carpitella's survey of Italian folk music for the Columbia World Library, conducted in 1953 and 1954, with the cooperation of the BBC and the Accademia di Santa Cecilia in Rome, helped capture a snapshot of a multitude of important traditional folk styles shortly before they disappeared. The pair amassed one of the most representative folk song collections of any culture. From Lomax's Spanish and Italian recordings emerged one of the first theories explaining the types of folk singing that predominate in particular areas, a theory that incorporates work style, the environment, and the degrees of social and sexual freedom.

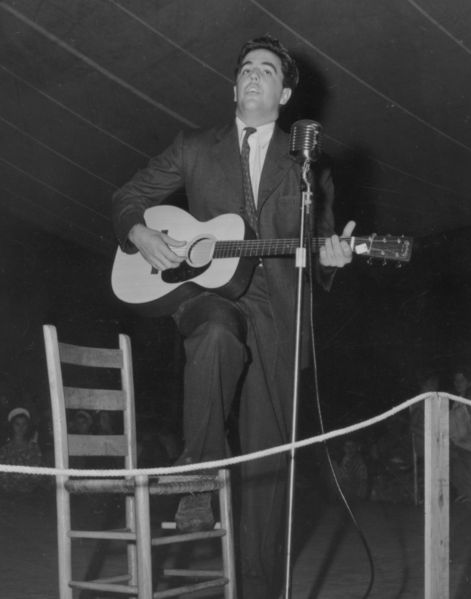

Upon his return to New York in 1959, Lomax produced a concert, Folksong '59," in Carnegie Hall, featuring Arkansas singer Jimmy Driftwood; the Selah Jubilee Singers and Drexel Singers (gospel groups); Muddy Waters and Memphis Slim (blues); Earl Taylor and the Stoney Mountain Boys (bluegrass); Pete Seeger, Mike Seeger (urban folk revival); and The Cadillacs (a rock and roll group). The occasion marked the first time rock and roll and bluegrass were performed on the Carnegie Hall Stage. "The time has come for Americans not to be ashamed of what we go for, musically, from primitive ballads to rock 'n' roll songs," Lomax told the audience. According to Izzy Young, the audience booed when he told them to lay down their prejudices and listen to rock 'n' roll. In Young's opinion, "Lomax put on what is probably the turning point in American folk music . . . . At that concert, the point he was trying to make was that Negro and white music were mixing, and rock and roll was that thing."

Alan Lomax married Elizabeth Lyttleton Harold in February 1937. They were married for 12 years and had a daughter, Anna. Elizabeth assisted him in recording in Haiti, Alabama, Appalachia, and Mississippi, and wrote radio scripts of folk operas featuring American music that were broadcast over the BBC home service as part of the war effort, as well as conducting lengthy interviews with folk music personalities including Reverend Gary Davis. He also did important field work with Elizabeth Barnicle and Zora Neale Hurston in Florida and the Bahamas (1936); with John Work and Lewis Jones in Mississippi (1941 and 42); with folksingers Robin Roberts and Jean Ritchie in Ireland (1950); with his second wife Antoinette Marchand in the Caribbean (1961); with Joan Halifax in Morocco; and with his daughter, Anna L. Wood. All those who assisted and worked with him were accurately credited on the resultant Library of Congress and other recordings, as well as in his many books and publications.

Alan Lomax met 20 year old English folk singer Shirley Collins while living in London. The two were romantically involved and lived together for some years. When Lomax obtained a contract from Atlantic Records to re-record some the U.S. artists he had recorded in the 1940s, using improved recording equipment, Collins accompanied him. Their folk song collecting trip to the Southern states lasted from July to November 1959 and resulted in many hours of recordings, featuring performers such as Almeda Riddle, Hobart Smith, Wade Ward, Charlie Higgins and Bessie Jones and culminated in the discovery of Mississippi Fred McDowell. Recordings from this trip were issued under the title Sounds of the South and some were also featured in the Coen brothers’ film Oh Brother, Where Art Thou. Lomax wanted to marry her but when their trip was over, Collins returned to England and instead married Austin John Marshall. In an interview in The Guardian newspaper, Friday March 21 2008, Collins was miffed that Alan Lomax's 1993 history of blues music, The Land Where The Blues Began, barely mentioned her. "All it said was, 'Shirley Collins was along for the trip'. It made me hopping mad. I wasn't just 'along for the trip'. I was part of the recording process, I made notes, I drafted contracts, I was involved in every part". Collins decided to rectify the perceived omission in her memoir America Over the Water, published in 2004. Collins described her arrival in America 1959 in an interview with Johan Kugelberg:

Kugelberg: Lomax met you?

Collins: He was on the dockside with Anne, his daughter. . . .. I think I arrived in April and I don't think we went south until August. It took quite a long time to get the money together; it kept falling through. I think Columbia was going to pay for it at one point, but they insisted he have a union engineer with him and someone extra like that -- that in situations we were going to be in would have been hopeless. So he refused, and they withdrew their funding. It was very last minute that the Ertegun brothers at Atlantic gave us the cash and we were gone within days of getting that money. Alan had wanted to do it earlier, but there was just no money to do it with. He had no money, ever. He was always living hand to mouth.

Kugelberg: That's the nature of somebody who is making the path as he's going along. Also as a sidebar, considering who the Ertegun brothers were at that point in time, it's surprising to me that they greenlighted that project at that point in time. I love that series, I think it's one of the great series of albums ever. It's surprising that Atlantic Records made that leap of faith because the series is sort of outside of their paradigm. So, those months were spent in New York?

Collins: We went to another place actually, we went to California, to the California Folk festival in Berkeley, this was sometime in the summer. And we stopped off in Chicago and stayed with Studs Terkel who was a hospitable man and his wonderful hospitable wife. Caught the train out to San Francisco from Chicago, which was an incredible experience. Sang at the Berkeley festival and met Jimmy Driftwood there for the first time. We all hit it off wonderfully.

Kugelberg: Your friends in England were dying of envy.

Collins: No, they didn't know.

Lomax married Antoinette Marchand on August 26, 1961.

In 1962, Lomax and singer and Civil Rights Activist Guy Carawan, music director at the Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, produced the album, Freedom in the Air: Albany Georgia, 1961-62, on Vanguard Records for the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee.

Lomax was a consultant to Carl Sagan for the Voyager Golden Record sent

into space on the 1977 Voyager Spacecraft to represent the music of the

earth. Music he helped choose included the blues, jazz, and rock 'n'

roll of Blind Willie Johnson, Louis Armstrong, and Chuck Berry; Andean panpipes and Navajo chants; a Sicilian sulfur miner's lament; polyphonic vocal music from the Mbuti Pygmies of Zaire, and the Georgians of the Caucasus; and a shepherdess song from Bulgaria by Valya Balkanska; in addition to Bach, Mozart, and Beethoven, and more. Musician Brian Eno had this to say about Lomax's later career: [He

later] turned his intelligent attentions to music from many other parts

of the world, securing for them a dignity and status they had not

previously been accorded. The “World Music” phenomenon arose partly

from those efforts, as did his great book, Folk Song Style and Culture.

I believe this is one of the most important books ever written about

music, in my all time top ten. It is one of the very rare attempts to

put cultural criticism onto a serious, comprehensible, and rational

footing by someone who had the experience and breadth of vision to be

able to do it.” As a member of the Popular Front and People's Songs in

the 1940s, Alan Lomax promoted what was then known as "One World" and

today is called multiculturalism. In the late forties he produced a

series of concerts at Town Hall and Carnegie Hall that presented

Flamenco guitar and Calypso, along with country blues, Appalachian music, Andean music, and jazz. His radio shows of the 40s and 50s explored musics of all the world's peoples. Lomax

recognized that folklore (like all forms of creativity) occurs at the

local and not the national level and flourishes not in isolation but in

fruitful interplay with other cultures. He was dismayed that mass

communications appeared to be crushing local cultural expressions and

languages. In 1950 he echoed anthropologist Bronisław Malinowski (1884 - 1942),

who believed the role of the ethnologist should be that of advocate for

primitive man (as indigenous people were then called), when he urged

folklorists to similarly advocate for the folk. Some, such as Richard Dorson,

objected that scholars shouldn't act as cultural arbiters, but Lomax

believed it would be unethical to stand idly by as the magnificent

variety of the world's cultures and languages was "grayed out" by

centralized commercial entertainment and educational systems. Although

he acknowledged potential problems with intervention, he urged that

folklorists with their special training actively assist communities in

safeguarding and revitalizing their own local traditions. Similar ideas had been put into practice by Benjamin Botkin,

Harold W. Thompson, and Louis C. Jones, who believed that folklore

studied by folklorists should be returned to its home communities to

enable it to thrive anew. They have been realized in the annual (since

1967) Smithsonian Folk Festival on the Mall in Washington, D.C. (for

which Lomax served as a consultant), in national and regional

initiatives by public folklorists and local activists in helping

communities gain recognition for their oral traditions and lifeways

both in their home communities and in the world at large; and in the

National Heritage Awards, concerts, and fellowships given by the NEA

and various State governments to master folk and traditional artists. In 2001, in the wake of the attacks in New York and Washington of Sept. 11, UNESCO's Universal Declaration of Cultural Diversity declared the safeguarding of languages and intangible culture on a par with

protection of individual human rights and as essential for human survival as biodiversity is for nature, ideas first articulated by Alan Lomax. From

1942 to 1979 Lomax was investigated and repeatedly interviewed by the

FBI, although nothing incriminating was ever found and the

investigation was eventually abandoned. Scholar and jazz pianist Ted Gioia uncovered and published extracts from Alan Lomax's 800-page FBI files. The

investigation appears to have started when an anonymous informant

reported overhearing Lomax's father telling guests in 1941 about what

he considered his son's Communist sympathies. Looking for leads, the

FBI seized on the fact that, as a teenager in the 1930s, Lomax had

transferred from Harvard to the University of Texas after being

arrested in Boston in connection with a political demonstration. In

1942 the FBI bizarrely sent agents to interview students at Harvard's

freshman dorm about Lomax's participation in a demonstration that had

occurred at Harvard ten years earlier (in 1932) in support of the

immigration rights of one Edith Berkman, a Jewish woman, dubbed the

"red flame" for her labor organizing activities among the textile

workers of Lawrence, Massachusetts, and threatened with deportation as

an allgeged "Communist agitator". Lomax

had been charged with disturbing the peace and fined $25.00. Miss

Berkman, however, had been cleared of all accusations against her and

was not deported. Nor had Lomax's Harvard academic record been affected

in any way by his activities in her defense. Nevertheless, the bureau

continued trying vainly to show that in 1932 Lomax had either

distributed Communist literature or made public speeches in support of

the Communist Party. Lomax

left Harvard in 1932 after a year of study there, because his father

lost his job and all his money during the depression and could no

longer afford to pay his tuition, and not for any political or academic

reasons. He probably also had wanted to be close to his newly bereaved

father, now a widower, and his 10-year old sister, Bess, who was now motherless. In

June 1942 the FBI approached the Librarian of Congress, Archibald

McLeish, attempting to have Lomax fired as Assistant in Charge of the

Library's Archive of American Folk Song. At the time, Lomax was

preparing for a field trip to the Mississippi Delta on behalf of the

Library, where he would make landmark recordings of Muddy Waters, Son

House, and David "Honeyboy" Edwards, among others. McLeish wrote to

Hoover defending Lomax: "I have studied the findings of these reports

very carefully. I do not find positive evidence that Mr. Lomax has been

engaged in subversive activities and I am therefore taking no

disciplinary action toward him." Nevertheless, according to Gioia: Yet

what the probe failed to find in terms of prosecutable evidence, it

made up for in speculation about his character. An FBI report dated

July 23, 1943, describes Lomax as possessing “an erratic, artistic

temperament” and a “bohemian attitude.” It says: “He has a tendency to

neglect his work over a period of time and then just before a deadline

he produces excellent results." The file quotes one informant who said

that “Lomax was a very peculiar individual, that he seemed to be very

absent-minded and that he paid practically no attention to his personal

appearance.” This same source adds that he suspected Lomax’s

peculiarity and poor grooming habits came from associating with the

hillbillies who provided him with folk tunes". Lomax, who was a founding member of People's Songs,

was in charge of campaign music for Henry A. Wallace's 1948

Presidential run on the Progressive Party ticket on a platform opposing

the arms race and supporting civil rights for Jews and African

Americans. Subsequently, Lomax was one of the performers listed in the

publication Red Channels as a possible Communist sympathizer and was consequently blacklisted from working in US entertainment industries. A 2007 BBC news article revealed that in the early '50s, the British MI5 placed Alan Lomax under surveillance as a suspected Communist. Its report concluded that although Lomax undoubtedly held "left wing"

views, there was no evidence he was a Communist. Released Sept. 4, 2007, a summary of his MI5 file reads as follows: Noted

American folk music archivist and collector Alan Lomax first attracted

the attention of the Security Service when it was noted that he had

made contact with the Romanian press attaché in London while he

was working on a series of folk music broadcasts for the BBC in 1952.

Correspondence ensued with the American authorities as to Lomax'

suspected membership of the Communist Party, though no positive proof

is found on this file. The Service took the view that Lomax' work

compiling his collections of world folk music gave him a legitimate

reason to contact the attaché, and that while his views (as

demonstrated by his choice of songs and singers) were undoubtedly left

wing, there was no need for any specific action against him. The

file contains a partial record of Lomax' movements, contacts and

activities while in Britain, and includes for example a police report

of the "Songs of the Iron Road" concert at St Pancras in December 1953.

His association with [blacklisted American] film director Joseph Losey is also mentioned. The

FBI again investigated Lomax in 1956 and sent a 68 page report to the

CIA and the Attorney General's office. However, William Tompkins,

assistant attorney general, wrote to Hoover that the investigation had

failed to disclose sufficient evidence to warrant prosecution or the

suspension of Lomax's passport. Then,

as late as 1979, an FBI report suggested that Lomax had recently

impersonated an FBI agent. The report appears to have been based on

mistaken identity. The person who reported the incident to the FBI said

that the man in question was around 43, about 5 feet 9 inches and 190

pounds. The FBI file notes that Lomax stood 6 feet tall, weighed 240

pounds and was 64 at the time: Lomax

resisted the FBI’s attempts to interview him about the impersonation

charges, but he finally met with agents at his home in November 1979.

He denied that he’d been involved in the matter but did note that he’d

been in New Hampshire in July 1979, visiting a film editor about a

documentary. The FBI’s report concluded that “Lomax made no secret of

the fact that he disliked the FBI and disliked being interviewed by the

FBI. Lomax was extremely nervous throughout the interview". The FBI investigation was concluded the following year, shortly after Lomax's 65th birthday.

Alan Lomax received the National Medal of Arts from President Reagan in 1986, a Library of Congress Living Legend Award in 2000, and was awarded an Honorary Doctorate in Philosophy from Tulane University in 2001. He won the National Book Critics Circle Award and the Ralph J. Gleason Music Book Award in 1993 for his book The Land Where the Blues Began,

connecting the story of the origins of blues music with the prevalence

of forced labor in the pre-World War II South (especially on the

Mississippi levees). Lomax also received a posthumous Grammy Trustees Award for his lifetime achievements in 2003. Jelly Roll Morton: The Complete Library of Congress Recordings by Alan Lomax (Rounder Records, 8 CDs boxed set) won in two categories at the 48th annual Grammy Awards ceremony held on Feb 8, 2006.