<Back to Index>

- Physicist Frits Zernike, 1888

- Painter Andrea del Sarto, 1486

- Civil Rights Activist Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, 1862

PAGE SPONSOR

Andrea del Sarto (1486/87 – 1530/1531) was an Italian painter from Florence, whose career flourished during the High Renaissance and early Mannerism. Though highly regarded during his lifetime as an artist senza errori ("without errors"), his renown was eclipsed after his untimely death by that of his contemporaries, Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael.

Andrea was born Andrea d'Agnolo di Francesco di Luca di Paolo del Migliore in Gualfonda, close to Florence, on 16 July in either 1486 or 1487, one of four children. Since his father, Agnolo, was a tailor (sarto), he became known as "del Sarto" ("tailor's son"). Since 1677 some have attributed the surname Vannucchi with little documentation. By 1494 Andrea was apprenticed to a goldsmith, and then to a woodcarver and painter named Gian Barile, with whom he remained until 1498. According to Vasari, he then apprenticed to Piero di Cosimo, and later with Raffaellino del Garbo (Carli).

Andrea and an older friend Franciabigio decided

to open a joint studio at a lodging together in the Piazza del Grano.

The first product of their partnership may have been the Baptism of Christ for the Florentine Compagnia dello Scalzo,

the beginning of a monochrome fresco series. By the time the

partnership was dissolved, Sarto's style bore the stamp of

individuality. It "is marked throughout his career by an interest,

exceptional among Florentines, in effects of colour and atmosphere and

by sophisticated informality and natural expression of emotion."

From 1509 to 1514 the brotherhood of the Servites employed Sarto, Franciabigio, and Andrea Feltrini in a programme of frescoes at Basilica della Santissima Annunziata di Firenze. Sarto completed three frescoes in the portico of the Servite convent illustrating the Life of Filippo Benizzi, a

Servite saint who died in 1285. He executed them rapidly, depicting the

saint sharing his cloak with a leper, cursing some gamblers, and

restoring a girl possessed with a devil.

These paintings met with respect, the correctness of the contours being

particularly admired, and earned for Sarto the nickname of "Andrea

senza errori" (Andrea the perfect). After these, the painter depicted

in two frescoes the death of S. Filippo and then children cured by

touching his garment; all five works were completed before the close of

1510. The Servites engaged him to do two more frescoes in the forecourt

of the Annunziata: a Procession of the Magi (or Adoration, containing a self portrait) finished in 1511. Towards 1512 he painted an Annunciation in the monastery of S. Gallo and a Marriage of Saint Catherine (Dresden).

By 1514 Andrea had finished his last two frescoes, including his masterpiece, the Birth of the Virgin, which fuses the influence of Leonardo, Ghirlandaio and Fra Bartolomeo. By November 1515 he had finished at the Scalzo the Allegory of Justice and the Baptist preaching in the desert, followed in 1517 by John Baptizing, and other subjects. Before the end of 1516 a Pietà of his composition, and afterwards a Madonna, were sent to the French Court. This led to an invitation from François I,

in 1518, and he journeyed to Paris in June of that year, along with his

pupil Andrea Squarzzella, leaving his wife, Lucrezia, in Florence. According to Giorgio Vasari, Andrea's pupil and biographer, Lucrezia wrote to Andrea and demanded he return to Italy. The King assented, but only on the understanding that his absence from France was

to be short. He then entrusted Andrea with a sum of money to be

expended in purchasing works of art for the French Court. By Vasari's

account, Andrea took the money and used it to buy himself a house in

Florence, thus ruining his reputation and preventing him from ever

returning to France. The story inspired Robert Browning's poem monologue "Andrea del Sarto Called the 'Faultless Painter'" (1855), but is now believed by some historians to be apocryphal. In 1520 he resumed work in Florence, and executed the Faith and Charity in the cloister of the Scalzo. These were succeeded by the Dance of the Daughter of Herodias, the Beheading of the Baptist, the Presentation of his head to Herod, an allegory of Hope, the "Apparition of the Angel to Zacharias" (1523), and the monochrome Visitation. This last was painted in the autumn of 1524, after Andrea had returned from Luco in Mugello, whence an outbreak of bubonic plague in Florence had driven him and his family. In 1525 he returned to paint in the Annunziata cloister the Madonna del Sacco, a lunette named

after a sack against which Joseph is represented propped. In this

painting the generous virgin's gown and her gaze indicate his influence

on the early style of pupil Pontormo. In 1523 Andrea painted a copy of the portrait group of Pope Leo X by Raphael. (Andrea's copy is now in the Naples Museum, while the original remains at the Pitti.) The Raphael painting was owned by Ottaviano de' Medici, and requested by Federico II Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua.

Unwilling to part with the original, Ottaviano retained Andrea to

produce a copy, which he passed to the Duke as the original. So

faithful was the imitation that even Giulio Romano,

who had himself manipulated the original to some extent, was completely

fooled; and, on showing the copy years afterwards to Vasari, who knew

the truth, he could only be convinced that it was not genuine when a

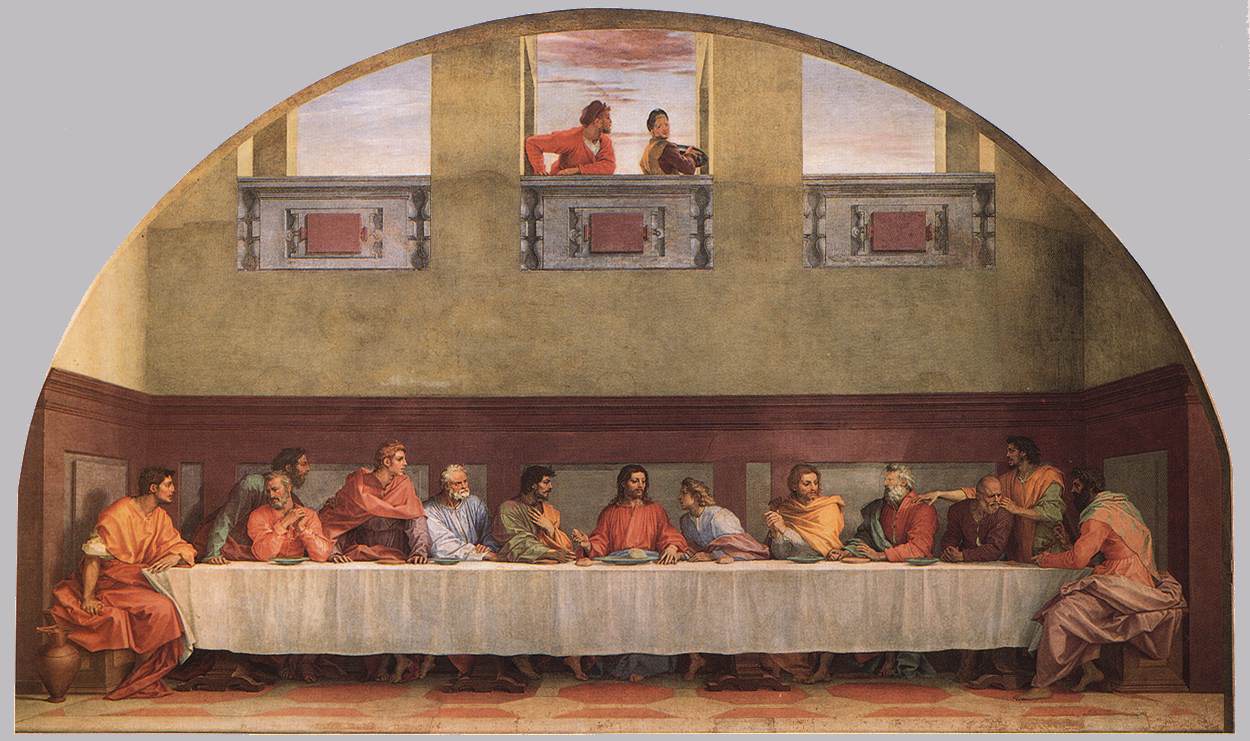

private mark on the canvas was pointed out to him by Vasari. Andrea's final work at the Scalzo was the Birth of the Baptist (1526). In the following year he completed his last important painting, a celebrated Last Supper at S. Salvi, near Florence, in which all the personages appear to be portraits. A number of his paintings are considered to be self-portraits. One is in the National Gallery, London, a half-figure, purchased in 1862. Another is at Alnwick Castle, a young man about twenty years, with his elbow on a table. Another youthful portrait is in the Uffizi Gallery, and the Pitti Palace contains more than one.

Perhaps the best known painting by Andrea del Sarto is the Madonna of the Harpies,

a depiction of the Virgin and child on a pedestal, flanked by angels

and two saints (Bonaventure or Francis, and John the Evangelist).

Originally completed in 1517 for the convent of San Francesco dei

Macci, the altarpiece now resides in the Uffizi. In an Italy swamped

with a tsunami of Madonnas, it would be easy to overlook this work;

however, this commonly copied scheme also lends itself to comparison of

his style with that of his contemporaries. The figures have a Leonardo-like

aura, and the stable pyramid of their composition provides a unified

structure. In some ways, his rigid adherence is more classical than

Leonardo da Vinci's but less so than Fra Bartolomeo's

representations of the Holy Family, but there is an elegance that is

lacking in the more sculptural paintings of other contemporaries. Andrea married Lucrezia (del Fede), widow of a hatter named Carlo, of Recanati, on 26 December 1512. Lucrezia appears in many of his paintings, often as a Madonna. However, Vasari describes her as "faithless, jealous, and vixenish with the apprentices." She is similarly characterized in Robert Browning's poem. Andrea died in Florence at age 43 during a pandemic of Bubonic Plague in either 1530 or 1531. He was buried unceremoniously in the church of the Servites. In Lives of the Artists, Vasari claimed Andrea received no attention at all from his wife during his terminal illness. However,

it was well-known at the time that plague was highly contagious, so it

has been speculated that Lucrezia was simply afraid to contract the

virulent and frequently fatal disease. If true, her caution was

well-founded, as she survived her husband by 40 years. It was Michelangelo who had introduced Vasari in

1524 to Andrea's studio. He is said to have thought very highly of

Andrea's talents. Of those who initially followed his style in

Florence, the most prominent would have been Jacopo Pontormo, but also Francesco Salviati and Jacopino del Conte.

Other lesser known assistants and pupils include Bernardo del Buda,

Lamberto Lombardi, Nannuccio Fiorentino, and Andrea Squazzella. Vasari,

however, was highly critical of his teacher, alleging that, though

having all the prerequisites of a great artist, he lacked ambition and

that divine fire of inspiration which animated the works of his more

famous contemporaries, like Leonardo, Michelangelo, and Raphael.