<Back to Index>

- Physicist Frits Zernike, 1888

- Painter Andrea del Sarto, 1486

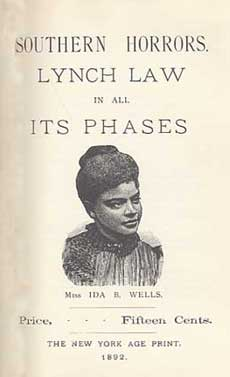

- Civil Rights Activist Ida Bell Wells-Barnett, 1862

PAGE SPONSOR

Ida Bell Wells-Barnett (July 16, 1862 – March 25, 1931) was an African American journalist, newspaper editor and, with her husband, newspaper owner Ferdinand L. Barnett, an early leader in the civil rights movement. She documented the extent of lynching in the United States, and was also active in the women's rights movement and the women's suffrage movement.

Ida Bell Wells was born in Holly Springs, Mississippi, in 1862, just before President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Her father James Wells was a carpenter and her mother was Elizabeth "Lizzie" Warrenton Wells. Both parents were slaves until freed at the end of the Civil War. Ida’s father James was a master at carpentry and known as a race man. He was also very interested in politics, but he never took office. Her mother Elizabeth was a cook for the Bolling household before she was torn apart from the family. She was a religious woman who was very strict with her children, for their best interests. Wells' parents took their children's education very seriously. They wanted their children to take advantage of having the opportunity to be educated and attend school. Wells attended the Freedmen's School Shaw University, now Rust College in Holly Springs. She was expelled from Rust College for her rebellious behavior and temper after confronting the President of the college. During her time at college, on a visit to her grandmother in Mississippi Valley, she received word that her hometown of Holly Springs had been hit by the Yellow Fever epidemic. When she was 16, both Wells' parents and her 10-month old brother, Stanley, died of yellow fever during an epidemic that swept through the South.

At a meeting following the funeral, friends and relatives decided that the six remaining Wells children would be sent to various aunts and uncles. Wells was devastated by the idea and, to keep the family together, dropped out of high school and found employment as a teacher in a black school. She was determined to keep her family together, even under the difficult circumstances. Her grandmother, Peggy Wells, along with other friends and relatives as well, stayed with the children during the week while she was away to teach; without this help she would have not been able to provide for the family. She used teaching as a way to support herself and her family, however she didn’t have a passion for it. She thought it was unfair that white teachers were making $80 a month when she was only making $30. This had caused her to find an interest in racial politics and improving education of blacks.

In 1883, Wells moved to Memphis. There she got a teaching job, and during her summer vacations she attended summer sessions at Fisk University in Nashville, whose graduates were well respected in the black community. She also attended LeMoyne Institute. Wells held strong political opinions and she upset many people with her views on women's rights. When she was 24, she wrote, "I will not begin at this late day by doing what my soul abhors; sugaring men, weak deceitful creatures, with flattery to retain them as escorts or to gratify a revenge."

On May 4, 1884, a Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad Company train conductor ordered Wells to give up her seat on the train and move to the smoking car, which was already crowded with other passengers. At the time, the Supreme Court had just struck down, in the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the federal Civil Rights Act of 1875, which banned racial discrimination in public accommodations. Several railroad companies were able to continue legal racial segregation of their passengers. Wells protested and refused to give up her seat 71 years before Rosa Parks. The conductor and two other men dragged Wells out of the car. When she returned to Memphis, she immediately hired an African American attorney to sue the railroad. Wells became a public figure in Memphis when she wrote a newspaper article, for "The Living Way," a black church weekly, about her treatment on the train. When her lawyer was paid off by the railroad, she hired a white attorney. She won her case on December 24, 1884 when the local circuit court granted her a $500 settlement. The railroad company appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, which reversed the lower court's ruling in 1885, concluding that, "We think it is evident that the purpose of the defendant in error was to harass with a view to this suit, and that her persistence was not in good faith to obtain a comfortable seat for the short ride." Wells was ordered to pay court costs.

While teaching elementary school, Wells was offered an editorial position for the Evening Star. She also wrote weekly articles for The Living Way weekly newspaper under the pen name "Iola."

She slowly gained a reputation for writing about the race issue in the

United States. In 1889, she became co-owner and editor of Free Speech and Headlight,

an anti-segregationist newspaper based at the Beale Street Baptist

Church in Memphis that published articles about racial injustice. In

March 1891, racial tensions were rising in Memphis. Violence was

becoming the norm, especially with the appearance of the KKK. A grocery store,

the People's Grocery Company, owned by three black men, Thomas Moss,

Calvin McDowell, and Henry Stewart, was perceived as taking away a

substantial amount of business from a white-owned grocery store that

was across the street. One night, while Wells was out of town in

Natchez, MS, selling newspaper subscriptions, an attack broke out when a

white mob invaded the grocery store, which ended in three white men

being shot and injured. Moss, McDowell, and Stewart, who were Wells'

friends, were jailed. A large lynch mob stormed the jail cells and killed them. After the lynching of her friends, Wells wrote an article in the Free Speech urging

blacks to leave Memphis: "There is, therefore, only one thing left to

do; save our money and leave a town which will neither protect our

lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in

the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood when accused

by white persons." Wells emphasized the public spectacle of the lynching. Over 6,000 blacks did leave; others organized boycotts of white-owned businesses. Being personally threatened with violence, Wells wrote in her autobiography that she bought a pistol: "They had made me an exile and threatened my life for hinting at the truth." The murder of her friends sparked Wells' interest in researching the real reason behind lynching. She began investigative journalism about lynching, looking at the charges given as reasons to lynch black men.

She wrote an article that implied that liaisons between black men and

white women were consensual. While she was away in Philadelphia, The Free Speech was

destroyed on May 27, 1892, three months after the murders of Moss,

Stewart, and McDowell. She went from Philadelphia to New York City. The New York Age printed

her articles as she continued her fight against lynching. Her speaking

abilities were tested for the first time when she was asked to speak in

front of many important African American women of the time. As

she spoke about the lynchings of Moss, McDowell, and Stewart, she began

to cry. Wells became the head of the Anti-Lynching Crusade, later

moving to Chicago to continue her work. She

was known as one of the most influential and inspiring black leaders of

the time, along with Fredrick Douglass. Wells and other black leaders,

among them Frederick Douglass, organized a boycott of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in

Chicago. Ida B. Wells, Frederick Douglass, Irvine Garland Penn and

Ferdinand L. Barnett wrote sections of a pamphlet to be distributed

during the exposition. Reasons Why the Colored American Is Not in the World's Columbian Exposition detailed the progress of blacks since their arrival in America and the workings of Southern lynchings. She later reported to Albion W. Tourgée that copies of the pamphlet had been distributed to over 20,000 people at the fair. After

the World's Fair in Chicago, Wells decided to stay in the city instead

of returning to New York City and took work with the Chicago Conservator, the 1893, oldest African American newspaper in the city. Also in 1893, Wells contemplated a libel suit

against two black Memphis attorneys. She again turned to

Tourgée, who had trained and practiced as a lawyer and judge,

for possible free legal help. Deeply in debt, Tourgée could not

afford to do the work, but he asked his friend Ferdinand L. Barnett if

he could. Barnett accepted the pro bono job. Ferdinand was born in Alabama.

Along with being a lawyer, he was the editor of the "Chicago

Conservator" in 1878. The first time Ida met Ferdinand was at a meeting

of the Ida B. Wells Club, where Ferdinand was president of the club.

Ferdinand was an assistant state attorney for 14 years. In 1895, he and Wells were married. She

set an early precedent as being one of the first married American women

to keep her own last name with her husband's. This was very unusual for

that time. The

two had four children: Charles, Herman, Ida, and Alfreda. In a chapter

of her autobiography titled "A Divided Duty", she explains the

difficulty she had splitting her time between her family and her job.

Wells continued to work after the birth of her first child, traveling

and bringing him along with her. Although she tried to balance the two

worlds, she was not as active and, as Susan B. Anthony said,

Wells "was distracted". She returned home after having her second child

because she could no longer balance her job with her family. She

received much support from other prolific social activists and her

fellow clubwomen. In his response to her article in the Free Speech,

Frederick Douglass expressed approval of Wells-Barnett's literature:

"You have done your people and mine a service… What a revelation of

existing conditions your writing has been for me".

Wells-Barnett took her campaign into Europe with the help of many

supporters. In 1896, Wells founded the National Association of Colored

Women, and also founded the National Afro-American Council, which later

became the NAACP. Wells formed the Women's Era Club, the first civic

organization for African-American women. This club later became the Ida

B. Wells Club, in honor of its founder. In

1899, Wells was struggling to manage a home life and a career life, but

she was still a fierce competitor in the anti-lynching circle. This was illustrated when The National Association of Colored Women's club

met that year in Chicago. To Wells' surprise, she was not invited to

take part in the festivities. When she confronted the president of the

club, Mrs. Terrell, Wells was told that Terrell had received letters

from the women of Chicago that if Wells were to take part in the club,

they would no longer aid the association. However, Wells later came to

find out that the real reason she had not been invited was because

of Mrs.Terrell's selfish intentions. Mrs. Terrell had been president of

the association 2 years' running and wanted to be elected a third time.

Mrs.Terrell thought the only way of doing that was to keep Wells out of

the picture. After

traveling through the British Isles and the United States teaching and

giving speeches to bring awareness to the lynching problems in America,

Wells settled in Chicago and worked to improve conditions for the

rapidly growing African American population there. The rapid increase

of African Americans into the population led to racial tensions much

like those in the South. There were also tensions between the African

American population and the immigrants from Europe, who were now in

competition for jobs. Wells spent the latter thirty years of her life

working on urban reform in Chicago. While there, she also raised her

family and worked on her autobiography. After her retirement Wells

wrote her autobiography, Crusade for Justice (1928).

The book, however, was never finished; in fact, it ends in the middle

of a sentence, in the middle of a word. She died of uremia in Chicago on March 25, 1931, at the age of 68. Ida

B. Wells took two tours to Europe on her campaign for justice, the

first in 1893 and the second in 1894. While she was in Europe she spent

her time in both Scotland and England, where she gave many speeches and

newspaper interviews. In 1893, Wells went to Great Britain at the behest of British Quaker Catherine Impey.

An opponent of imperialism and proponent of racial equality, Impey

wanted to be sure that the British public was informed about the

problem of lynching. Wells went to rally a new reform moral crusade to

the English. Although Wells and her speeches, complete with at least

one grisly photograph showing grinning white children posing beneath a

suspended corpse, caused a stir among audiences, they still remained

doubtful. Her intentions were to raise money and expose the United

States problem with lynching, but Wells was paid so little that she

could barely pay her travel expenses. Many

people that heard her speak were repulsed by the information they were

given. This helped to keep the audience interested and engaged in what

Wells was trying to educate them on. Christian churches in Europe did

not like Wells because she talked badly about American churches,

stating that they did not help her with her cause. Relationships

of mixed race were looked harshly upon in those times and were seen as

rape. This resulted in the lynching of black individuals (mostly men).

Wells, however, worked very hard to make a point that these

relationships were actually voluntary relations. Wells returned to Great Britain in 1894. Before leaving she called on the Editor of Daily Inter-Ocean, Mr. William Penn Nixon, and told him about her return to Britain. As she points out in her book Crusade for Justice, the Daily Inter-Ocean, a

Chicago based paper, was the only paper in America which had

persistently denounced lynching. Mr. Nixon asked her to write for the

newspaper while away, and she very gladly accepted the opportunity. In doing so, she became the first black woman to be a paid correspondent for a mainstream white newspaper. (Tourgée

had been writing a column for the same paper, which was the local

Republican Party organ and competitor to the Democratic Chicago Tribune.) Wells column was called “Ida B. Wells Abroad.” An example of an article that she wrote was called “In Pembroke Chapel.” This

specific article focused on her invitation to speak in the Pembroke

chapel whose reverend was C.F. Aked. She describes the reverend as “one

of the most advanced thinkers in the pulpit of today." He himself was not confident about the stories that Ida B. Wells told, but he went to New York for the World’s Fair and actually saw the reports on the Miller lynching in Bardwell, Kentucky. After

that point he knew that Ida B. Wells was telling the truth. She was

well accepted in Europe. Most of the people there were shocked about

the treatment of African Americans in the United States. Wells was

successful in spreading the news and getting people to formally release

statements saying they disapproved of the situation in America. On a

number of accounts, she was faced with people who protested what she

was saying, and in these moments she was able to support all of the

information with research and studies that she had found. Ida

B. Wells' two tours to Europe helped gain support for her cause. She

called for the formation of groups to formally protest the actions of

white Americans and the lynchings they commit. Wells was a major

influence for the formation of many groups across Europe, which helped

lead to the international pressure on America for equality. Frances

E. Willard, a white feminist, was the president of the Woman’s

Christian Temperance Union. She fought for women's suffrage. She and

Wells had many confrontations throughout the years, starting in 1890

and lasting until Willard’s death in 1898. The feud started over a

negative racial comment that Willard made. These confrontations took

place mostly in print, covering topics like race, lynching, and sexual

desire. Wells

did not pick just any random person with which to start a feud; she

thought long and hard before she attacked Willard for her many

weaknesses. Wells attacked Willard because of her reputation for

interracial communication and her persona as a woman of high Christian

moral character. Willard

went to Europe at the same time as one of Wells’ tours. While in

Europe, she gave an interview with the president of the Woman’s

Christian Temperance Union in England. In this interview, they really

tried to pull attention to the fact that Willard was very moral, trying

to make her sound like a wonderful person. Wells responded with a very

harshly written letter. She mentioned such things as, “after some

preliminary remarks on the terrible subject of lynching, Miss Willard

laughingly replies by cracking a joke.” She also points out that the

article was just trying to improve Willard’s reputation. This was a

common type of confrontation that took place between the two women. In 1892 she published a pamphlet titled Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, and A Red Record,

1892 – 1894, which documented research on lynching. Having examined

many accounts of lynching based on alleged "rape of white women," she

concluded that Southerners concocted rape as an excuse to hide their

real reason for lynchings: black economic progress, which threatened

not only white Southerners' pocketbooks, but also their ideas about

black inferiority. The

lesson this teaches and which every Afro-American should ponder well,

is that a Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black

home, and it should be used for that protection which the law refuses

to give. When the white man who is always the aggressor knows he runs

as great a risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim

does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life. The more the

Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he has to do so,

the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched. The Red Record is

a one hundred page pamphlet describing lynching in the United States

since the Emancipation Proclamation, while also describing blacks’

struggles since the time of the Emancipation Proclamation. The Red Record begins

by explaining the alarming severity of the lynching situation in the

United States. An ignorance of lynching in the U.S., according to Ida,

developed over a span of ten years. Ida talks about slavery, saying the

black man’s body and soul were owned by the white man. The soul was

dwarfed by the white man, and the body was preserved because of its

value. Ida mentions that “ten thousand Negroes have been killed in cold

blood, without the formality of judicial trial and legal execution,”

therefore launching her campaign against lynching in this pamphlet, The Red Record.

Frederick Douglass wrote an article explaining three eras of Southern

barbarism and the excuses that coincided with each. Ida goes into

detail about each excuse. The

first excuse that Ida explains is the “necessity of the white man to

repress and stamp out alleged ‘race riots.’” Once the Civil War ended,

there were many riots supposedly being planned by blacks; whites

panicked and resisted them forcefully. The

second excuse came during the Reconstruction Era: blacks were lynched

because whites feared “Negro Domination” and wanted to stay powerful in

the government. Wells encouraged those threatened to move their

families somewhere safe. The

third excuse was: Blacks had “to be killed to avenge their assaults

upon women.” Ida explains that any relationship between a white woman

and a black man was considered rape during that time period. In this

article she states, “Nobody in this section of the country believes the

old threadbare lie that Negro men rape white women.” Ida lists fourteen

pages of statistics concerning lynching done from 1892 – 1895; she also

includes pages of graphic stories detailing lynching done in the South.

Ida credits the findings to white correspondents, white press bureaus,

and white newspapers. The Red Record was a huge pamphlet, not only in size, but in influence. Throughout her life Wells was militant in her demands for equality and justice for African-Americans and

insisted that the African-American community win justice through its

own efforts. Since her death interest in her life and legacy has only

grown. Her life is the subject of a widely performed musical drama,

which debuted in 2006, by Tazewell Thompson, Constant Star. The play sums her up: "...A

woman born in slavery, she would grow to become one of the great

pioneer activists of the Civil Rights movement. A precursor of Rosa Parks, she was a suffragist, newspaper editor and

publisher, investigative journalist, co-founder of the NAACP, political

candidate, mother, wife, and the single most powerful leader in the

anti-lynching campaign in America. A dynamic, controversial,

temperamental, uncompromising race woman, she broke bread and crossed

swords with some of the movers and shakers of her time: Frederick Douglass, Susan B. Anthony, Marcus Garvey, Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frances Willard, and President McKinley. By any fair assessment, she was a seminal figure in Post-Reconstruction America." On February 1, 1990, the United States Postal Service issued a 25 cent postage stamp in her honor. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante listed Ida B. Wells on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.