<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier, 1811

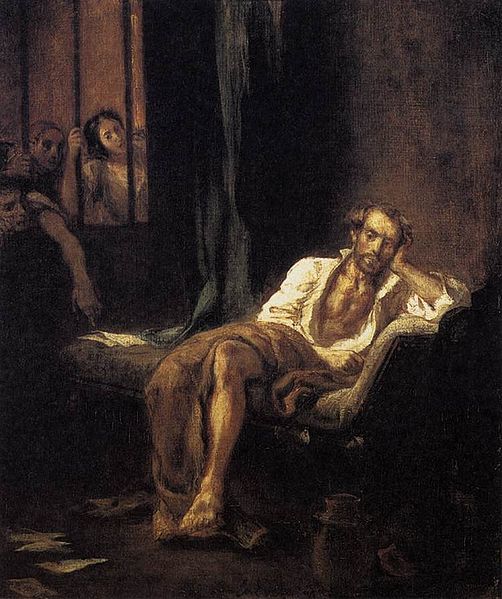

- Poet Torquato Tasso, 1544

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom James Harold Wilson, 1916

PAGE SPONSOR

Torquato Tasso (11 March 1544 – 25 April 1595) was an Italian poet of the 16th century, best known for his poem La Gerusalemme liberata (Jerusalem Delivered, 1580), in which he depicts a highly imaginative version of the combats between Christians and Muslims at the end of the First Crusade, during the siege of Jerusalem. He suffered from mental illness and died a few days before he was due to be crowned as the king of poets by the Pope. Until the beginning of the 19th century, Tasso remained one of the most widely read poets in Europe.

Born in Sorrento, he was the son of Bernardo Tasso, a nobleman of Bergamo and an epic and lyric poet of considerable fame in his day, and his wife Porzia de Rossi, a noblewoman from Tuscany. His father had for many years been secretary in the service of Ferrante Sanseverino, prince of Salerno, and his mother was closely connected with the most illustrious Neapolitan families. The prince of Salerno came into collision with the Spanish government of Naples, was outlawed, and was deprived of his hereditary fiefs. Tasso's father shared in this disaster of his patron. He was proclaimed a rebel to the state, together with his son Torquato, and his patrimony was sequestered. These things happened during the boy's childhood. In 1552 he was living with his mother and his only sister Cornelia at Naples, pursuing his education under the Jesuits, who had recently opened a school there. The precocity of intellect and the religious fervour of the boy attracted general admiration. At the age of eight he was already famous.

Soon after this date he joined his father, who then resided in great poverty, an exile and without occupation, in Rome. News reached them in 1556 that Porzia Tasso had died suddenly and mysteriously at Naples. Her husband was firmly convinced that she had been poisoned by her brother with the object of getting control over her property. As it subsequently happened, Porzia's estate never descended to her son; and the daughter Cornelia married below her birth, at the instigation of her maternal relatives. Tasso's father was a poet by predilection and a professional courtier. Therefore, when an opening at the court of Urbino was offered in 1557, Bernardo Tasso gladly accepted it.

The young Torquato, a handsome and brilliant lad, became the companion in sports and studies of Francesco Maria della Rovere, heir to the duke of Urbino. At Urbino a society of cultivated men pursued the aesthetical and literary studies which were then in vogue. Bernardo Tasso read cantos of his Amadigi to the duchess and her ladies, or discussed the merits of Homer and Virgil, Trissino and Ariosto, with the duke's librarians and secretaries. Torquato grew up in an atmosphere of refined luxury and somewhat pedantic criticism, both of which gave a permanent tone to his character.

At Venice,

where his father went to superintend the printing of his own epic,

Amadigi (1560), these influences continued. He found himself the pet

and prodigy of a distinguished literary circle. But Bernardo had

suffered in his own career so seriously from dependence on the Muses

and the nobility that he now determined on a lucrative profession for

his son. Torquato was sent to study law at Padua. Instead of applying himself to law, the young man bestowed all his attention upon philosophy and poetry. Before the end of 1562, he had produced a narrative poem called Rinaldo, which was meant to combine the regularity of the Virgilian with the attractions of the romantic epic. In the attainment of this object, and in all the minor qualities of style and handling, Rinaldo showed

such marked originality that its author was proclaimed the most

promising poet of his time. The flattered father allowed it to be

printed; and, after a short period of study at Bologna, he consented to his son's entering the service of Cardinal Luigi d'Este. In 1565, Tasso for the first time set foot in that castle at Ferrara which was destined for him to be the scene of so many glories, and such cruel sufferings. After the publication of Rinaldo he had expressed his views upon the epic in some Discourses on the Art of Poetry, which committed him to a distinct theory and gained for him the

additional celebrity of a philosophical critic. The age was nothing if

not critical; but it may be esteemed a misfortune for the future author

of the Gerusalemme that

he should have started with pronounced opinions upon art. Essentially a

poet of impulse and instinct, he was hampered in production by his own

rules. The

five years between 1565 and 1570 seem to have been the happiest of

Tasso's life, although his father's death in 1569 caused his

affectionate nature profound pain. Young, handsome, accomplished in all

the exercises of a well-bred gentleman, accustomed to the society of

the great and learned, illustrious by his published works in verse and

prose, he became the idol of the most brilliant court in Italy. The

first two books of his five hundred odd love poems were sequences

addressed to his first loves, Lucrezia Bendidio and Laura Peperara, court ladies and illustrious singers. The princesses Lucrezia and Leonora d'Este,

both unmarried, both his seniors by about ten years, took him under

their protection. He was admitted to their familiarity. He owed much to

the constant kindness of both sisters. In 1570 he traveled to Paris with the cardinal. Frankness

of speech and a certain habitual want of tact caused a disagreement

with his worldly patron. He left France next year, and took service

under Duke Alfonso II of Ferrara. The most important events in Tasso's biography during the following four years are the publication of Aminta in 1573 and the completion of Gerusalemme Liberata in 1574. Aminta is a pastoral drama of very simple plot, but of exquisite lyrical charm. It appeared at the moment when music, under Palestrina's impulse, was becoming the main art of Italy. The honeyed melodies and sensuous melancholy of Aminta exactly suited and interpreted the spirit of its age. Its influence, in opera and cantata, was felt through two successive centuries. The Gerusalemme Liberata occupies

a larger space in the history of European literature, and is a more

considerable work. Yet the commanding qualities of this epic poem,

those which revealed Tasso's individuality, and which made it

immediately pass into the rank of classics, beloved by the people no

less than by persons of culture, are akin to the lyrical graces of Aminta. Its hero was Godfrey of Bouillon, the leader of the first Crusade; the climax of the epic was the capture of the holy city. It

was finished in Tasso's thirty-first year; and when the manuscripts lay

before him the best part of his life was over, his best work had been

already accomplished. Troubles immediately began to gather round him. Instead of having the courage to obey his own instinct, and to publish the Gerusalemme as he had conceived it, he yielded to the critical scrupulosity which formed a secondary feature of his character. The

poem was sent in manuscript to several literary men of eminence, Tasso

expressing his willingness to hear their strictures and to adopt their

suggestions unless he could convert them to his own views. The result

was that each of these candid friends, while expressing in general high

admiration for the epic, took some exception to its plot, its title,

its moral tone, its episodes or its diction, in detail. One wished it

to be more regularly classical; another wanted more romance. One hinted

that the Inquisition would not tolerate its supernatural machinery; another demanded the excision of its most charming passages, the loves of Armida, Clorinda and Erminia. Tasso had to defend himself against all these ineptitudes and

pedantries, and to accommodate his practice to the theories he had

rashly expressed. As in the Rinaldo, so also in the Jerusalem Delivered,

he aimed at ennobling the Italian epic style by preserving strict unity

of plot and heightening poetic diction. He chose Virgil for his model,

took the first crusade for subject, infused the fervour of religion into his conception of the hero Godfrey.

But his natural bias was for romance. In

spite of the poet's ingenuity and industry the stately main theme

evinced less spontaneity of genius than the romantic episodes with

which he adorned it, as he had done in Rinaldo. Godfrey, a mixture of pious Aeneas and Tridentine Catholicism, is not the real hero of the Gerusalemme. Fiery and passionate Rinaldo, Ruggiero, melancholy impulsive Tancredi, and the chivalrous Saracens with whom they clash in love and war, divide the reader's interest and divert it from Goffredo. The action of the epic turns on Armida,

the beautiful witch, sent forth by the infernal senate to sow discord

in the Christian camp. She is converted to the true faith by her

adoration for a crusading knight, and quits the scene with a phrase of

the Virgin Mary on her lips. Brave Clorinda dons armour like Marfisa, fighting in a duel with her devoted lover and receiving baptism from his hands at the time of her pathetic death; Erminia seeks

refuge in the shepherds' hut. These lovely pagan women, so touching in

their sorrows, so romantic in their adventures, so tender in their

emotions, rivet the readers' attention, while the battles, religious

ceremonies, conclaves and stratagems of the campaign are easily

skipped. The truth is that Tasso's great invention as an artist was the

poetry of sentiment. Sentiment, not sentimentality, gives value to what

is immortal in the Gerusalemme.

It was a new thing in the 16th century, something concordant with a

growing feeling for woman and with the ascendant art of music. This

sentiment, refined, noble, natural, steeped in melancholy, exquisitely

graceful, pathetically touching, breathes throughout the episodes of the Gerusalemme, finds metrical expression in the languishing cadence of

its mellifluous verse, and sustains the ideal life of those seductive

heroines whose names were familiar as household words to all Europe in

the 17th and 18th centuries. Tasso's

self-chosen critics were not men to admit what the public has since

accepted as incontrovertible. They vaguely felt that a great and

beautiful romantic poem was imbedded in a dull and not very correct

epic. In their uneasiness they suggested every course but the right

one, which was to publish the Gerusalemme without further dispute. Tasso,

already overworked by his precocious studies, by exciting court-life

and exhausting literary industry, now grew almost mad with worry. His

health began to fail him. He complained of headache, suffered from malarious fevers, and wished to leave Ferrara. The Gerusalemme was laid in manuscript upon a shelf. He opened negotiations with the court of Florence for

an exchange of service. This irritated the duke of Ferrara. Alfonso

hated nothing more than to see courtiers leave him for a rival duchy.

Alfonso thought, moreover, that, if Tasso were allowed to go, the Medici would

get the coveted dedication of that already famous epic. Therefore he

bore with the poet's humours, and so contrived that the latter should

have no excuse for quitting Ferrara. Meanwhile, through the years 1575,

1576 and 1577, Tasso's health grew worse. Jealousy

inspired the courtiers to malign and insult him. His irritable and

suspicious temper, vain and sensitive to slights, rendered him only too

easy a prey to their malevolence. In the 1570s Tasso developed a

persecution mania which led to legends about the restless, half-mad,

and misunderstood author. He became consumed by thoughts that his

servants betrayed his confidence, fancied he had been denounced to the Inquisition,

and expected daily to be poisoned. Literary and political events

surrounding him contributed to upsets and the mental state, with

troubles, stress and social troubles escalating. In

the autumn of 1576 Tasso quarrelled with a Ferrarese gentleman,

Maddalo, who had talked too freely about some same-sex love affair; the

same year he wrote a letter to his homosexual friend Luca Scalabrino

dealing with his own love for a twenty-one year old young man Orazio

Ariosto; in the summer of 1577 he drew his knife upon a servant in the

presence of Lucrezia d'Este, duchess of Urbino. For this excess he was arrested; but the duke released him, and took him for a change of air to his country seat of Belriguardo. What happened there is not known. Some

biographers have surmised that a compromising liaison with Leonora

d'Este came to light, and that Tasso agreed to feign madness in order

to cover her honor. but of this there is no proof. It is only certain

that from Belriguardo he returned to a Franciscan convent at Ferrara,

for the express purpose of attending to his health. There the dread of

being murdered by the duke took firm hold on his mind. He escaped at

the end of July, disguised himself as a peasant, and went on foot to

his sister at Sorrento. The

conclusions were that Tasso, after the beginning of 1575, became the

victim of a mental malady, which, without amounting to actual insanity,

rendered him fantastical and insupportable, a cause of anxiety to his

patrons. There

is no evidence whatsoever that this state of things was due to an

overwhelming passion for Leonora. The duke, contrary to his image as a

tyrant, showed considerable forbearance. He was a rigid and not

sympathetic man, as egotistical as a princeling of that age was wont to

be. But to Tasso he was never cruel; unintelligent perhaps, but far

from being that monster of ferocity which has been painted. The

subsequent history of his connection with the poet corroborates this

view. While

at Sorrento, Tasso yearned for Ferrara. The court-made man could not

breathe freely outside its charmed circle. He wrote humbly requesting

to be taken back. Alfonso consented, provided Tasso would agree to

undergo a medical course of treatment for his melancholy. When he

returned, which he did with alacrity under those conditions, he was

well received by the ducal family. All

might have gone well if his old maladies had not revived. Scene

followed scene of irritability, moodiness, suspicion, wounded vanity

and violent outbursts. In the summer of 1578 he ran away again; travelled through Mantua, Padua, Venice, Urbino, Lombardy. In September he reached the gates of Turin on foot, and was courteously entertained by Emmanuel Philibert, Duke of Savoy.

Wherever he went, wandering like the world's rejected guest, he met

with the honour due to his illustrious name. Great folk opened their

houses to him gladly, partly in compassion, partly in admiration of his

genius. But he soon wearied of their society, and wore their kindness

thin by his querulous peevishness. It seemed, moreover, that life was

intolerable to him outside Ferrara. Accordingly he once more opened

negotiations with the duke; and in February 1579 he again set foot in

the castle. Alfonso was about to contract his third marriage, this time with a princess of the house of Mantua.

He had no children, and unless he got an heir, there was a probability

that his state would fall, as it did subsequently, to the Holy See.

The nuptial festivals, on the eve of which Tasso arrived, were not

therefore an occasion of great rejoicing for the elderly bridegroom. As

a forlorn hope he had to wed a third wife; but his heart was not

engaged and his expectations were far from sanguine. Tasso,

preoccupied as always with his own sorrows and his own sense of

dignity, made no allowance for the troubles of his master. Rooms below

his rank, he thought, had been assigned him; the Duke was engaged.

Without exercising common patience, or giving his old friends the

benefit of a doubt, he broke into terms of open abuse, behaved like a

lunatic, and was sent off without ceremony to the madhouse of St. Anna.

This happened in March 1579; and there he remained until July 1586.

Duke Alfonso's long-sufferance at last had given way. He firmly

believed that Tasso was insane, and he felt that if he were so St. Anna

was the safest place for him. Tasso had put himself in the wrong by his

intemperate conduct, but far more by that incomprehensible yearning

after the Ferrarese court which made him return to it again and yet

again. It

was no doubt very irksome for a man of Tasso's pleasure-loving,

restless and self-conscious spirit to be kept for more than seven years

in confinement. Yet one must weigh the facts of the case rather than

the fancies which have been indulged regarding them. After the first

few months of his incarceration he obtained spacious apartments,

received the visits of friends, went abroad attended by responsible

persons of his acquaintance, and corresponded freely with whomsoever he

chose to address. The letters written from St. Anna to the princes and

cities of Italy, to warm well-wishers, and to men of the highest

reputation in the world of art and learning, form the most valuable

source of information, not only on his then condition, but also on his

temperament at large. It is singular that he spoke always respectfully,

even affectionately, of the Duke. Some

critics have attempted to make it appear that he was hypocritically

kissing the hand which had chastised him, with the view of being

released from prison, but no one who has impartially considered the

whole tone and tenor of his epistles will adopt this opinion. What

emerges clearly from them is that he labored under a serious mental

disease, and that he was conscious of it. Meanwhile,

he occupied his uneasy leisure with copious compositions. The mass of

his prose dialogues on philosophical and ethical themes, which is very

considerable, belong to the years of imprisonment in St. Anna. Except

for occasional odes or sonnets — some written at request and only

rhetorically interesting, a few inspired by his keen sense of suffering

and therefore poignant — he neglected poetry. But everything which fell

from his pen during this period was carefully preserved by the

Italians, who, while they regarded him as a lunatic, somewhat

illogically scrambled for the very offscourings of his wit. Nor

can it be said that society was wrong. Tasso had proved himself an

impracticable human being; but he remained a man of genius, the most

interesting personality in Italy. Long ago his papers had been sequestered. In the year 1580, he heard that part of the Gerusalemme was

being published without his permission and without his corrections. The

following year, the whole poem was given to the world, and in the

following six months seven editions issued from the press. The prisoner

of St. Anna had no control over his editors; and from the masterpiece

which placed him on the level of Petrarch and Ariosto he

never derived one penny of pecuniary profit. A rival poet at the court

of Ferrara undertook to revise and edit his lyrics in 1582. This was Battista Guarini;

and Tasso, in his cell, had to allow odes and sonnets, poems of

personal feeling, occasional pieces of compliment, to be collected and

emended, without lifting a voice in the matter. A few years later, in 1585, two Florentine pedants of the Crusca Academy declared war against the Gerusalemme.

They loaded it with insults, which seem to those who read their

pamphlets now mere parodies of criticism. Yet Tasso felt bound to

reply; and he did so with a moderation and urbanity which prove him to

have been not only in full possession of his reasoning faculties, but a

gentleman of noble manners also. The man, like Hamlet,

was distraught through ill-accommodation to his circumstances and his

age; brain-sick he was undoubtedly; and this is the Duke of Ferrara's

justification for the treatment he endured. In the prison he bore

himself pathetically, peevishly, but never ignobly. He showed a

singular indifference to the fate of his great poem, a rare magnanimity

in dealing with its detractors. His own personal distress, that

terrible malaise of imperfect insanity, absorbed him. What

remained over, untouched by the malady, unoppressed by his

consciousness thereof, displayed a sweet and gravely-toned humanity.

The oddest thing about his life in prison is that he was always trying

to place his two nephews, the sons of his sister Cornelia, in

court-service. One of them he attached to Guglielmo I, Duke of Mantua, the other to Ottavio Farnese, Duke of Parma. After all his father's and his own lessons of life, he had not learned that the court was to be shunned like Circe by

an honest man. In estimating Duke Alfonso's share of blame, this wilful

idealization of the court by Tasso must be taken into account. That man

is not a tyrant's victim who moves heaven and earth to place his

sister's sons with tyrants. In 1586 Tasso left St. Anna at the solicitation of Vincenzo Gonzaga, Prince of Mantua. He followed his young deliverer to the city by the Mincio,

basked awhile in liberty and courtly pleasures, enjoyed a splendid

reception from his paternal town of Bergamo, and produced a meritorious

tragedy called Torrismondo.

But only a few months had passed when he grew discontented. Vincenzo

Gonzaga, succeeding to his father's dukedom of Mantua, had scanty

leisure to bestow upon the poet. Tasso felt neglected. In the autumn of

1587 he journeyed through Bologna and Loreto to Rome, and taking up his

quarters there with an old friend, Scipione Gonzaga, now Patriarch of Jerusalem. Next year he wandered off to Naples, where he wrote a dull poem on Monte Oliveto.

In 1589 he returned to Rome, and took up his quarters again with the

patriarch of Jerusalem. The servants found him insufferable, and turned

him out of doors. He fell ill, and went to a hospital. The patriarch in

1590 again received him. But Tasso's restless spirit drove him forth to

Florence. The Florentines said, "Actum est de eo." Rome once more, then

Mantua, then Florence, then Rome, then Naples, then Rome, then

Naples — such is the weary record of the years 1590-94. He endured a

veritable Odyssey of

malady, indigence and misfortune. To Tasso everything came amiss. He

had the palaces of princes, cardinals, patriarchs, nay popes, always

open to him. Yet he could rest in none. Gradually, in spite of all

veneration for the sacer vates, he made himself the laughing stock and bore of Italy. His health grew ever feebler and his genius dimmer. In 1592, he gave to the public a revised version of the Gerusalemme. It was called the Gerusalemme Conquistata.

All that made the poem of his early manhood charming he rigidly erased.

The versification was degraded; the heavier elements of the plot

underwent a dull rhetorical development. During the same year a prosaic

composition in Italian blank verse, called Le Sette Giornate,

saw the light. Nobody reads it now. It is only mentioned as one of

Tasso's dotages — a dreary amplification of the first chapter of Genesis. It

is singular that just in these years, when mental disorder, physical

weakness, and decay of inspiration seemed dooming Tasso to oblivion, his old age was cheered with brighter rays of hope. Pope Clement VIII ascended the papal chair in 1592. He and his nephew, Cardinal Aldobrandini of San Giorgio,

determined to befriend the poet. In 1594, they invited him to Rome.

There he was to receive the crown of laurels, as Petrarch had been

crowned, on the Capitol. Worn

out with illness, Tasso reached Rome in November. The ceremony of his

coronation was deferred because Cardinal Aldobrandini had fallen ill,

but the pope assigned him a pension; and, under the pressure of

pontifical remonstrance, Prince Avellino, who held Tasso's maternal

estate, agreed to discharge a portion of his claims by payment of a

yearly rent-charge. At

no time since Tasso left St. Anna had the heavens apparently so smiled

upon him. Capitolian honors and money were now at his disposal. Yet

fortune came too late. Before he wore the crown of poet laureate,

or received his pensions, he ascended to the convent of Sant'Onofrio,

on a stormy 1 April 1595. Seeing a cardinal's coach toil up the steep

Trasteverine Hill, the monks came to the door to greet it. From the

carriage stepped Tasso and told the prior he had come to die with him. He

died in Sant'Onofrio in April 1595. He was just past fifty-one; and the

last twenty years of his existence had been practically and

artistically ineffectual. At the age of thirty-one the Gerusalemme, was accomplished. The world too was already ringing with the music of Aminta.

More than this Tasso had naught to give to literature but those

succeeding years of derangement, exile, imprisonment, poverty and hope

deferred endear the man to readers. Elegiac and querulous as he must

always appear, Tasso was loved better in the Romantic period because he suffered through nearly a quarter of a century of slow decline and unexplained misfortune. Rime (Rhymes), nearly two thousand lyrics in nine books, were written between 1567 and 1593. Influenced by Petrarca's Canzoniere, they develop a research for musicality and are rich of delicate images and subtle sentiments; Galealto re di Norvegia, (1573-4) an unfinished tragedy, which later was finished with a new title: Re Torrismondo (1587). It is influenced by Sophocles's and Seneca's tragedies, and tells the story of princess Alvida of Norway, who is forcibly married off to the Goth king Torrismondo, when she is devoted to her childhood friend, king Germondo of Sweden; Dialoghi (Dialogues),

written between 1578 and 1594. These 28 texts deal with various issues,

from moral ones (love, virtue, nobility) to more mundane ones (masks,

play, courtly style, beauty). Sometimes Tasso touches major themes of

his time: for instance, religion vs. intellectual freedom; Christianity

vs. Islam at Lepanto; Discorsi del poema eroico, published in 1594. This is the main text to understand Tasso's poetics and was probably written during the long years of composing and revising Gerusalemme Liberata;

The disease Tasso began to suffer from is now believed to be schizophrenia. Legends describe him wandering the streets of Rome half

mad, convinced that he was being persecuted. At times he was imprisoned

for his own safety by the Duke in St. Anne's lunatic asylum. Though he

was never fully cured, he was able to function and resumed his writing.

The Gerusalemme was published by his friends Angelo Ingegneri and Febo Bonna, mostly with the consent of the poet.