<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier, 1811

- Poet Torquato Tasso, 1544

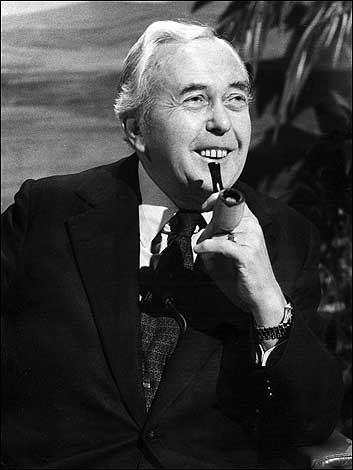

- Prime Minister of the United Kingdom James Harold Wilson, 1916

PAGE SPONSOR

James Harold Wilson, Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, KG, OBE, FRS, PC (11 March 1916 – 24 May 1995) was a British Labour politician. One of the most prominent British politicians of the latter half of the 20th century, he served two terms as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, firstly from 1964 to 1970, and again from 1974 to 1976. He emerged as Prime Minister after more general elections than any other 20th century premier, contesting five general elections and winning four of them (in 1964, 1966, February 1974 and October 1974). He is the most recent British Prime Minister to have served non-consecutive terms.

Harold Wilson first served as Prime Minister in the 1960s, during a period of low unemployment and relative economic prosperity (though also of significant problems with the UK's external balance of payments). His second term in office began in 1974, when a period of economic crisis was beginning to hit most Western countries. On both occasions, economic concerns were to prove a significant constraint on his governments' ambitions. Wilson's own approach to socialism placed emphasis on efforts to increase opportunity within society, for example through change and expansion within the education system, allied to the technocratic aim of taking better advantage of rapid scientific progress, rather than on the left's traditional goal of promoting wider public ownership of industry. While he did not challenge the Party constitution's stated dedication to nationalisation head-on, he took little action to pursue it. Though generally not at the top of Wilson's personal areas of priority, his first period in office was notable for substantial legal changes in a number of social areas, including the liberalisation of censorship, divorce, homosexuality, immigration and abortion, as well as the abolition of capital punishment, due in part to the initiatives of backbench MPs who had the support of Roy Jenkins during his time as Home Secretary. Overall, Wilson is seen to have managed a number of difficult political issues with considerable tactical skill, including such potentially divisive issues for his party as the role of public ownership, British membership of the European Community, and the Vietnam War. Nonetheless, his stated ambition of substantially improving Britain's long-term economic performance remained largely unfulfilled.

Wilson was born in Huddersfield, England on 11 March 1916, an almost exact contemporary of his rival, Edward Heath (born

9 July 1916). He came from a political family: his father James Herbert

Wilson (1882 – 1971) was a works chemist who had been active in the Liberal Party and then joined the Labour Party. His mother Ethel (née Seddon;

1882 – 1957) was a schoolteacher prior to her marriage. When Wilson was

eight, he visited London and a later-to-be-famous photograph was taken

of him standing on the doorstep of 10 Downing Street. Wilson won a scholarship to attend the local grammar school, Royds Hall Secondary School, Huddersfield. His education was disrupted in 1931 when he contracted typhoid fever after drinking contaminated milk on a Scouts' outing and took months to recover. The next year his father, working as an industrial chemist, was made redundant and moved to Spital on the Wirral to find work. Wilson attended the sixth form at the Wirral Grammar School for Boys, where he became Head Boy.

Wilson

did well at school and, although he missed getting a scholarship, he

obtained an exhibition; which, when topped up by a county grant,

enabled him to study Modern History at Jesus College, Oxford, from 1934. At Oxford, Wilson was moderately active in politics as a member of the Liberal Party but was later influenced by G.D.H. Cole to join the Labour Party. After his first year, he changed his field of study to Philosophy, Politics and Economics. He graduated with "an outstanding first class Bachelor of Arts degree, with alphas on every paper" in the final examinations. He

also received exceptional testimonials from his tutors, including a

comment from one that "he is, far and away, the ablest man I have

taught so far".

Although Wilson had two abortive attempts at an All Souls Fellowship,

he continued in academia, becoming one of the youngest Oxford

University dons of the century at the age of 21. He was a lecturer in Economic History at New College from 1937, and a Research Fellow at University College during the period 1938 to 1945. For much of this time, he was a research assistant to William Beveridge, the Master of the College, working on the issues of unemployment and the trade cycle.

In 1940, in the chapel of Mansfield College, Oxford, he married (Gladys) Mary Baldwin who remained his wife until his death. Mary Wilson became a published poet. They had two sons, Robin and Giles (named after Giles Alington); Robin became a Professor of Mathematics, and Giles became a teacher. Both his sons went to the same independent school, University College School, in Hampstead. In their twenties, his sons were under a kidnap threat from the IRA. After becoming a teacher at a comprehensive school for two years, Giles later returned to teaching, becoming a Maths master at Salisbury Cathedral School. In November 2006 it was reported that Giles had given up his teaching job and become a train driver for South West Trains. He is a devotee of rail restoration, specifically the Tarka Line. On

the outbreak of the Second World War, Wilson volunteered for service

but was classed as a specialist and moved into the civil service

instead. Most of his war was spent as a statistician and economist for

the coal industry. He was Director of Economics and Statistics at the Ministry of Fuel and Power 1943–4, and received an OBE for his services. He was to remain passionately interested in statistics. As President of the Board of Trade,

he was the driving force behind the Statistics of Trade Act 1947, which

is still the authority governing most economic statistics in Great

Britain. He was instrumental as Prime Minister in appointing Claus Moser as head of the Central Statistical Office, and was president of the Royal Statistical Society in 1972–73. As the War drew to an end, he searched for a seat to fight at the impending general election. He was selected for Ormskirk, then held by Stephen King-Hall.

Wilson accidentally agreed to be adopted as the candidate immediately

rather than delay until the election was called, and was therefore

compelled to resign from the Civil Service. He served as Praelector in

Economics at University College between his resignation and his

election to the House of Commons. He also used this time to write A New Deal for Coal which used his wartime experience to argue for nationalisation of the coal mines on the basis of improved efficiency. In the 1945 general election, Wilson won his seat in the Labour landslide. To his surprise, he was immediately appointed to the government as Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Works. Two years later, he became Secretary for Overseas Trade, in which capacity he made several official trips to the Soviet Union to negotiate supply contracts. Conspiracy minded commentators would later seek to raise suspicions about these trips. On 14 October 1947, Wilson was appointed President of the Board of Trade and,

at 31, became the youngest member of the Cabinet in the 20th century.

He took a lead in abolishing some of the wartime rationing, which he

referred to as a "bonfire of controls". His role in internal debates

during the summer of 1949 over whether or not to devalue sterling, in

which he was perceived to have played both sides of the issue,

tarnished his reputation in both political and official circles. In the general election of 1950, his constituency was altered and he was narrowly elected for the new seat of Huyton, Merseyside. Wilson was becoming known as a left-winger and joined Aneurin Bevan and John Freeman in resigning from the government in April 1951 in protest at the introduction of National Health Service (NHS) medical charges to meet the financial demands imposed by the Korean War.

After the Labour Party lost the general election later that year, he

was made chairman of Bevan's 'Keep Left' group, but shortly thereafter

he distanced himself from Bevan. By coincidence, it was Bevan's further

resignation from the Shadow Cabinet in 1954 that put Wilson back on the front bench (as a spokesman, initially, on finance).

Wilson

soon proved to be a very effective Shadow Minister. One of his

procedural moves caused a delay to the progress of the Government's

Finance Bill in 1955, and his speeches as Shadow Chancellor from 1956

were widely praised for their clarity and wit. He coined the term "gnomes of Zurich"

to describe Swiss bankers whom he accused of pushing the pound down by

speculation. In the meantime, he conducted an inquiry into the Labour

Party's organisation following its defeat in the 1955 general election,

which compared the Party organisation to an antiquated "penny farthing"

bicycle, and made various recommendations for improvements. Unusually,

Wilson combined the job of Chairman of the House of Commons Public Accounts Committee with that of Shadow Chancellor from 1959 , holding the chairmanship of the PAC from 1959 to 1963. Wilson

steered a course in intra-party matters in the 1950s and early 1960s

that left him fully accepted and trusted by neither the left nor the

right. Despite his earlier association with the left-of-centre Aneurin Bevan, in 1955 he backed the right-of-centre Hugh Gaitskell against Bevan for the party leadership. He

then launched an opportunistic but unsuccessful challenge to Gaitskell

in 1960, in the wake of the Labour Party's 1959 defeat, Gaitskell's

controversial attempt to ditch Labour's commitment to nationalisation

in the shape of the Party's Clause Four,

and Gaitskell's defeat at the 1960 Party Conference over a motion

supporting Britain's unilateral nuclear disarmament. Wilson also

challenged for the deputy leadership in 1962 but was defeated by George Brown. Following these challenges, he was moved to the position of Shadow Foreign Secretary. Hugh

Gaitskell died unexpectedly in January 1963, just as the Labour Party

had begun to unite and to look to have a good chance of being elected

to government. Wilson became the left candidate for the leadership. He

defeated George Brown, who was hampered by a reputation as an erratic figure, in a straight contest in the second round of balloting, after James Callaghan, who had entered the race as an alternative to Brown on the right of the party, had been eliminated in the first round. Wilson's 1964 election campaign was aided by the Profumo Affair, a 1963 ministerial sex scandal that had mortally wounded the Conservative government of Harold Macmillan and was to taint his successor Sir Alec Douglas-Home,

even though Home had not been involved in the scandal. Wilson made

capital without getting involved in the less salubrious aspects. (Asked

for a statement on the scandal, he reportedly said "No comment... in

glorious Technicolor!").

Home was an aristocrat who had given up his title as Lord Home to sit

in the House of Commons. To Wilson's comment that he was the 14th Earl of Home, Home retorted, "I suppose Mr. Wilson is the fourteenth Mr. Wilson". At

the Labour Party's 1963 annual conference, Wilson made possibly his

best-remembered speech, on the implications of scientific and

technological change, in

which he argued that "the Britain that is going to be forged in the

white heat of this revolution will be no place for restrictive

practices or for outdated measures on either side of industry". This

speech did much to set Wilson's reputation as a technocrat not tied to

the prevailing class system.

Labour won the 1964 general election with a narrow majority of four seats, and Wilson became Prime Minister.

This was an insufficient parliamentary majority to last for a full

term, and after 18 months, a second election in March 1966 returned

Wilson with the much larger majority of 96. In

economic terms, Wilson's first three years in office were dominated by

an ultimately doomed effort to stave off the devaluation of the pound. He inherited an unusually large external deficit on the balance of trade.

This partly reflected the preceding government's expansive fiscal

policy in the run-up to the 1964 election, and the incoming Wilson team

tightened the fiscal stance in response. Many British economists

advocated devaluation, but Wilson resisted, reportedly in part out of

concern that Labour, which had previously devalued sterling in 1949,

would become tagged as "the party of devaluation". After

a costly battle, market pressures forced the government into

devaluation in 1967. Wilson was much criticised for a broadcast in

which he assured listeners that the "pound in your pocket" had not lost

its value. It was widely forgotten that his next sentence had been

"prices will rise". Economic performance did show some improvement

after the devaluation, as economists had predicted. The devaluation,

with accompanying austerity measures, successfully restored the balance

of payments to surplus by 1969. However, this unexpectedly turned into

a small deficit again in 1970. The bad figures were announced just

before polling in the 1970 general election, and are often cited as one of the reasons for Labour's defeat. A main theme of Wilson's economic approach was to place enhanced emphasis on "indicative economic planning." He created a new Department of Economic Affairs to

generate ambitious targets that were in themselves supposed to help

stimulate investment and growth. The government also created a Ministry of Technology (shortened

to Mintech) to support the modernisation of industry. Though now out of

fashion, faith in this approach was at the time by no means confined to

the Labour Party — Wilson built on foundations that had been laid by his

Conservative predecessors, in the shape, for example, of the National Economic Development Council (known as "Neddy") and its regional counterparts (the "little Neddies"). The

continued relevance of industrial nationalisation (a centerpiece of the

post-War Labour government's programme) had been a key point of

contention in Labour's internal struggles of the 1950s and early 1960s.

Wilson's predecessor as leader, Hugh Gaitskell, had tried in 1960 to tackle the controversy head-on, with a proposal to expunge Clause Four (the

public ownership clause) from the party's constitution, but had been

forced to climb down. Wilson took a characteristically more subtle

approach. He threw the party's left wing a symbolic bone with the

renationalisation of the steel industry, but otherwise left Clause Four

formally in the constitution but in practice on the shelf. Wilson made periodic attempts to mitigate inflation through wage-price controls, better known in the UK as "prices and incomes policy" (as

with indicative planning, such controls — though now generally out of

favour — were widely adopted at that time by governments of different

ideological complexions, including the Nixon administration in the

United States). Partly as a result of this reliance, the government

tended to find itself repeatedly injected into major industrial

disputes, with late-night "beer and sandwiches at Number Ten" an almost

routine culmination to such episodes. Among the more damaging of the

numerous strikes during Wilson's periods in office was a six-week

stoppage by the National Union of Seamen, beginning shortly after Wilson's re-election in 1966, and conducted, he claimed, by "politically motivated men". With

public frustration over strikes mounting, Wilson's government in 1969

proposed a series of changes to the legal basis for industrial

relations (labour law) in the UK, which were outlined in a White Paper "In Place of Strife" put forward by the Employment Secretary Barbara Castle. Following a confrontation with the Trades Union Congress, however, which strongly opposed the proposals, and internal dissent from Home Secretary James Callaghan,

the government substantially backed-down from its intentions. Some

elements of these changes were subsequently to be revived (in modified

form) during the premiership of Margaret Thatcher. Wilson's

administration made a variety of changes to the tax system. Largely

under the influence of the Hungarian-born economists Nicholas Kaldor and Thomas Balogh,

an idiosyncratic "selective employment tax (SET)" was introduced that

was designed to tax employment in the service sectors while subsidising

employment in manufacturing (the rationale proposed by its economist

authors derived largely from claims about potential economies of scale

and technological progress, but Wilson in his memoirs stressed the

tax's revenue raising potential). The SET did not long survive the

return of a Conservative government. Of longer term significance,

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) was introduced for the first time in the UK on

6 April 1965. Wilson's first period in office witnessed a range of social reforms, including the abolition of capital punishment, decriminalisation of sex between men in private, liberalisation of abortion law and the abolition of theatre censorship. The Divorce Reform Act was passed by parliament in 1969 (and came into effect in 1971). Such reforms were mostly via private member's bills on 'free votes'

in line with established convention, but the large Labour majority

after 1966 was undoubtedly more open to such changes than previous

parliaments had been. The government effectively supported the passage

of these bills by granting them the necessary parliamentary time. It

more or less made people more equal. Wilson

personally, coming culturally from a provincial non-conformist

background, showed no particular enthusiasm for much of this agenda (which some linked to the "permissive society"), but the reforming climate was especially encouraged by Roy Jenkins during his period at the Home Office. Wilson's 1966–70 term witnessed growing public concern over the level of immigration to the United Kingdom. The issue was dramatised at the political level by the famous "Rivers of Blood speech" by the Conservative politician Enoch Powell,

warning against the dangers of immigration, which led to Powell's

dismissal from the Shadow Cabinet. Wilson's government adopted a

two-track approach. While condemning racial discrimination (and

adopting legislation to make it a legal offence), Wilson's Home

Secretary James Callaghan introduced significant new restrictions on the right of immigration to the United Kingdom. Education

held special significance for a socialist of Wilson's generation, in

view of its role in both opening up opportunities for children from

working class backgrounds and enabling the UK to seize the potential

benefits of scientific advances. Wilson continued the rapid creation of

new universities, in line with the recommendations of the Robbins Report,

a bipartisan policy already in train when Labour took power. However,

the economic difficulties of the period deprived the tertiary system of

the resources it needed. Nevertheless, university expansion remained a

core policy. One notable effect was the first entry of women into

university education in significant numbers. Wilson also deserves credit for grasping the concept of an Open University,

to give adults who had missed out on tertiary education a second chance

through part-time study and distance learning. His political commitment

included assigning implementation responsibility to Baroness Jennie Lee, the widow of Aneurin Bevan, the charismatic leader of Labour's Left wing whom Wilson had joined in resigning from the Attlee cabinet. Wilson's record on secondary education is, by contrast, highly controversial. A fuller description is in the article Education in England. Two factors played a role. Following the Education Act 1944 there was disaffection with the tripartite system of academically oriented Grammar schools for a small proportion of "gifted" children, and Technical and Secondary Modern schools for the majority of children. Pressure grew for the abolition of the selective principle underlying the "eleven plus", and replacement with Comprehensive schools which would serve the full range of children. Comprehensive education became Labour Party policy. Labour

pressed local authorities to convert grammar schools, many of them

cherished local institutions, into comprehensives. Conversion continued

on a large scale during the subsequent Conservative Heath administration, although the Secretary of State, Mrs Margaret Thatcher,

ended the compulsion of local governments to convert. While the

proclaimed goal was to level school quality up, many felt that the

grammar schools' excellence was being sacrificed with little to show in

the way of improvement of other schools. Critically handicapping

implementation, economic austerity meant that schools never received

sufficient funding. A

second factor affecting education was change in teacher training,

including introduction of "progressive" child-centred methods, abhorred

by many established teachers. In parallel, the profession became

increasingly politicised. The status of teaching suffered and is still

recovering. Few

nowadays question the unsatisfactory nature of secondary education in

1964. Change was overdue. However, the manner in which change was

carried out is certainly open to criticism. The issue became a priority

for ex-Education Secretary Margaret Thatcher when she came to office as

prime minister in 1979. Another

major controversy of the first Wilson term was the decision that the

government could not fulfil its long-held promise to raise the school

leaving age to 16, due to the investment required in infrastructure

such as extra classrooms and teachers. Baroness Jennie Lee considered resigning in protest, but narrowly decided against this in the

interests of party unity. It was left to Margaret Thatcher to carry out the change, during the Heath government. In 1966, Wilson was created the first Chancellor of the newly created University of Bradford, a position he held until 1985. Among

the more challenging political dilemmas Wilson faced during his two

terms in government and his two spells in Opposition before 1964 and

between 1970 and 1974 was the issue of British membership of the European Community,

the forerunner of the present European Union. An entry attempt had been

issued in July 1961 by the Macmillan government, and negotiated by Edward Heath as Lord Privy Seal, but was vetoed in 1963 by French President Charles de Gaulle. The Labour Party in Opposition had been divided on the issue, with former party leader Hugh Gaitskell having come out in 1962 in opposition to Britain joining the Community. After

initially hesitating over the issue, Wilson's Government in May 1967

lodged the UK's second application to join the European Community. Like

the first, though, it was vetoed by de Gaulle in November that year. Following

his victory in the 1970 election (and helped by de Gaulle's fall from

power in 1969), the new prime minister Edward Heath negotiated

Britain’s admission to the EC, alongside Denmark and Ireland in 1973.

The Labour Party in opposition continued to be deeply divided on the

issue, and risked a major split. Leading opponents of membership

included Richard Crossman, who was for two years (1970–72) the editor of New Statesman,

at that time the leading left-of-centre weekly journal, which published

many polemics in support of the anti-EC case. Prominent among Labour

supporters of membership was Roy Jenkins. Wilson

in opposition showed political ingenuity in devising a position that

both sides of the party could agree on, opposing the terms negotiated

by Heath but not membership in principle. Labour's 1974 manifesto

included a pledge to renegotiate terms for Britain's membership and

then hold a referendum on whether to stay in the EC on the new terms.

This was a constitutional procedure without precedent in British

history. Following

Wilson's return to power, the renegotiations with Britain's fellow EC

members were carried out by Wilson himself in tandem with Foreign

Secretary James Callaghan, and they toured the capital cities of Europe meeting their European counterparts (some commentators have suggested that their co-operation in this exercise may have been

the source of a close relationship between the two men which is claimed

to have assisted a smooth change-over when Wilson retired from office).

The discussions focused primarily on Britain's net budgetary contribution

to the EC. As a small agricultural producer heavily dependent on

imports, the UK suffered doubly from the dominance of: (i) agricultural spending in the EC budget, and (ii) agricultural import taxes as a source of EC revenues. During the renegotiations, other EEC members conceded, as a partial offset, the establishment of a significant European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), from which it was clearly agreed that the UK would be a major net beneficiary. In

the subsequent referendum campaign, rather than the normal British

tradition of "collective responsibility", under which the government

takes a policy position which all cabinet members are required to

support publicly, members of the Government were free to present their

views on either side of the question. The electorate voted on 5 June 1975 to continue membership, by a substantial majority.

Prior United States military involvement in Vietnam intensified following the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964. US President Lyndon Johnson brought pressure to bear for at least a token involvement of British military units in the Vietnam War. Wilson consistently avoided any commitment of British forces, giving as reasons British military commitments to the Malayan Emergency and British co-chairmanship of the 1954 Geneva Conference which agreed the cessation of hostilities and internationally supervised elections in Vietnam. His

government offered some rhetorical support for the US position (most

prominently in the defence offered by the Foreign Secretary Michael Stewart in a much-publicised "teach-in"

or debate on Vietnam). On at least one occasion the British government

made an unsuccessful effort to mediate in the conflict. On 28 June 1966

Wilson 'dissociated' his Government from American bombing of the cities

of Hanoi and Haiphong. In his memoirs, Wilson writes of “selling LBJ a

bum steer” a reference to Johnson’s Texas origins, which conjured up

images of cattle and cowboys in British minds. Wilson's

approach of maintaining close relations with the US while pursuing an

independent line on Vietnam has attracted new interest in the light of

the different approach taken by the Blair government vis-a-vis Britain's participation in the Iraq War (2003). Since World War II, Britain's presence in the Far East had

gradually been run down. Former British colonies, whose defence had

provided much of the rationale for a British military presence in the

region, moved towards independence under British governments of both

parties. Successive UK Governments also became conscious of the cost to

the exchequer and the economy of maintaining major forces abroad (in

parallel, several schemes to develop strategic weaponry were abandoned

on the grounds of cost, for example, the Blue Streak missile and the TSR2 aircraft). In 1967, as the result of a defence review made by Defence Secretary Denis Healey, Wilson announced that Britain would withdraw its military forces from major bases “East of Suez”, primarily in Malaysia, Singapore and Aden. While criticised in right-wing circles at the time, over the

longer-term the decision can be seen as a logical culmination of the

withdrawal from Britain's colonial-era political and military

commitments in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and elsewhere that had

been underway under British governments of both parties since the

Second World War — and of the parallel switch of Britain's emphasis to

its European identity. Wilson was known for his strong pro-Israel views. He was a particular friend of Israeli Premier Golda Meir, though her time in office largely coincided with Wilson’s 1970 – 1974 hiatus. Another associate was German Chancellor Willy Brandt; all three were members of the Socialist International. In 1960, Prime Minister Harold Macmillan made his important Wind of Change speech to the Parliament of South Africa in Cape Town. This heralded independence for many British colonies in

Africa. The British “retreat from Empire” had made headway by 1964 and

was to continue during Wilson’s administration. However, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland came to present serious problems. The Federation was set up in 1953, and was an amalgamation of the Protectorates of Northern Rhodesia and Nyasaland and the colony of Southern Rhodesia. After struggles for independence, the Federation was dissolved in 1963 and the states of Zambia and Malawi achieved independence. However, the colony of Southern Rhodesia, which had been

the economic powerhouse of the Federation, was not granted

independence, principally because of the regime in power. The colony

bordered South Africa to the south and its governance was heavily influenced by the apartheid regime, then headed by Hendrik Verwoerd. Wilson refused to grant independence to the white minority government headed by Rhodesian Prime Minister Ian Smith which

showed little inclination to extend political influence to the native

African population, let alone to grant majority rule. Smith’s defiant

response was a Unilateral Declaration of Independence, timed to coincide with Armistice Day at

11.00 am on 11 November 1965, an attempt to garner support in the UK by

reminding people of the contribution of the colony to the war effort

(Smith himself had been a Spitfire pilot). Smith was personally vilified in the British media. Wilson’s immediate recourse was to the United Nations, and in 1965, the Security Council imposed sanctions, which were to last until official independence in 1979. This involved British warships blockading the port of Beira to

try to cause economic collapse in Rhodesia. Wilson was applauded by

most nations for taking a firm stand on the issue (and none extended

diplomatic recognition to the Smith regime). A number of nations did

not join in with sanctions, undermining their efficiency. Certain

sections of public opinion started to question their efficacy, and to

demand the toppling of the regime by force. Wilson declined, however,

to intervene in Rhodesia with military force, believing the UK

population would not support such action against their "kith and kin".

The two leaders met for discussions aboard British warships, Tiger in 1966 and Fearless in

1968. Smith subsequently attacked Wilson in his memoirs, accusing him

of delaying tactics during negotiations and alleging duplicity; Wilson

responded in kind, questioning Smith's good faith and suggesting that

Smith had moved the goal-posts whenever a settlement appeared in sight. The matter was still unresolved at the time of Wilson’s resignation in 1976. Elsewhere in Africa, trouble developed in Nigeria, brought about by the ethnic diversity of the country and the wealth being generated by the nascent oil industry. Wilson's government felt disinclined to interfere in the internal affairs of a fellow Commonwealth nation and supported the government of General Yakubu Gowon during the Nigerian Civil War of 1967 – 1970. By

1969, the Labour Party was suffering serious electoral reverses. In May

1970, Wilson responded to an apparent recovery in his government's

popularity by calling a general election, but, to the surprise of most

observers, was defeated at the polls by the Conservatives under Heath. Wilson

survived as leader of the Labour party in opposition. Economic

conditions during the 1970s were becoming more difficult for the UK and

many other western economies, and the Heath government in its turn was

buffeted by economic adversity and industrial unrest (notably including

confrontation with the coalminers). When Labour won more seats (though fewer votes) than the Conservative Party in February 1974, and Heath was unable to persuade the Liberals to form a coalition, Wilson returned to 10 Downing Street on 4 March 1974 as Prime Minister of a minority Labour Government. He gained a three-seat majority in another election later that year, on 10 October 1974. One of the key issues addressed during his second period in office was the referendum on British membership of the EEC. In the late 1960s, Wilson's earlier government had witnessed the outbreak of The Troubles in Northern Ireland. In response to a request from the Stormont government, the government agreed to deploy the British Army in an effort to maintain the peace. Out

of office in the autumn of 1971, Wilson formulated a 16-point, 15 year

programme that was designed to pave the way for the unification of

Ireland. The proposal was welcomed, in principle, by the Heath

government at the time but never put into effect. In May 1974, when back in office as leader of a minority government, Wilson condemned the Unionist-controlled Ulster Workers' Strike as a "sectarian strike"

which was "being done for sectarian purposes having no relation to this

century but only to the seventeenth century". However he refused to

pressurise a reluctant British Army to face down the loyalist paramilitaries

who were intimidating utility workers. In a televised speech later, he

referred to the "loyalist" strikers and their supporters as "spongers"

who expected Britain to pay for their lifestyles. The strike was eventually successful in breaking the power-sharing Northern Ireland executive. On 11 September 2008, BBC Radio Four's Document programme claimed to have unearthed a secret plan – codenamed Doomsday – which proposed to cut all constitutional ties with Northern Ireland and transform the province into an independent dominion. Document went on to claim that the Doomsday plan was devised mainly by Wilson and was

kept a closely guarded secret. The plan then allegedly lost momentum,

due in part, it was claimed, to warnings made by both the then Foreign

Secretary, James Callaghan and the Taoiseach as to its viability.

On

16 March 1976, Wilson surprised the nation by announcing his

resignation as Prime Minister (taking effect on 5 April 1976). He

claimed that he had always planned on resigning at the age of sixty,

and that he was physically and mentally exhausted. As early as the late

1960s, he had been telling intimates, like his doctor Sir Joseph Stone

(later Lord Stone of Hendon),

that he did not intend to serve more than eight or nine years as Prime

Minister. Roy Jenkins has suggested that Wilson may have been motivated

partly by the distaste for politics felt by his loyal and

long-suffering wife, Mary. Beyond this, by 1976 he might already have been aware of the first stages of early-onset Alzheimer's disease, which was to cause both his formerly excellent memory and his powers of concentration to fail dramatically. Queen Elizabeth II came to dine at 10 Downing Street to mark his resignation, an honour she has bestowed on only one other Prime Minister, Sir Winston Churchill (although she did dine at Downing Street at Tony Blair's invitation, to celebrate her 80th birthday).

Wilson's Prime Minister's Resignation Honours included

many businessmen and celebrities, along with his political supporters.

His choice of appointments caused lasting damage to his reputation,

worsened by the suggestion that the first draft of the list had been

written by Marcia Williams on lavender notepaper (it became known as the "Lavender List"). Roy Jenkins notes

that Wilson's retirement "was disfigured by his, at best, eccentric

resignation honours list, which gave peerages or knighthoods to some

adventurous business gentlemen, several of whom were close neither to

him nor to the Labour Party." Some of those whom Wilson honoured included Lord Kagan, the inventor of Gannex, who was eventually imprisoned for fraud, and Sir Eric Miller, who later committed suicide while under police investigation for corruption. Six candidates stood in the first ballot to replace him, in order of votes they were: Michael Foot, James Callaghan, Roy Jenkins, Tony Benn, Denis Healey and Anthony Crosland.

In the third ballot on 5 April, Callaghan defeated Foot in a

parliamentary vote of 176 to 137, thus becoming Wilson's successor as

Prime Minister and leader of the Labour Party, and remained prime

minister until May 1979, when Labour lost the general election to the Tories and Margaret Thatcher became Britain's first female prime minister. As Wilson wished to remain an MP after leaving office, he was not immediately given the peerage customarily offered to retired Prime Ministers, but instead was created a Knight of the Garter. On leaving the House of Commons in 1983, he was created Baron Wilson of Rievaulx, after Rievaulx Abbey, in the north of his native Yorkshire. A life-long Gilbert and Sullivan fan, in 1975, Wilson joined the Board of Trustees of the D'Oyly Carte Trust at the invitation of Sir Hugh Wontner, who was then the Lord Mayor of London. Not long after Wilson's retirement, his mental deterioration from Alzheimer's disease began to be apparent, and he did not appear in public after 1988 when he unveiled the Clement Attlee statue at Limehouse Library. He was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1985, and died a decade later from it in May 1995, at the age of 79. His memorial service was held in Westminster Abbey on 13 July 1995. He is buried at St. Mary's Old Church, St. Mary's on the Isles of Scilly. His epitaph is Tempus Imperator Rerum (Time the Commander of All Things).