<Back to Index>

- Philosopher George Berkeley, 1685

- Sculptor Pierre Jean David (David d'Angers), 1788

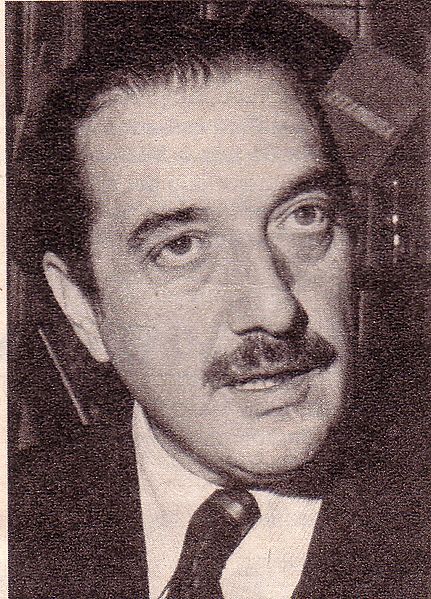

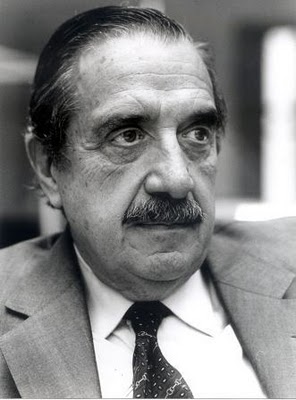

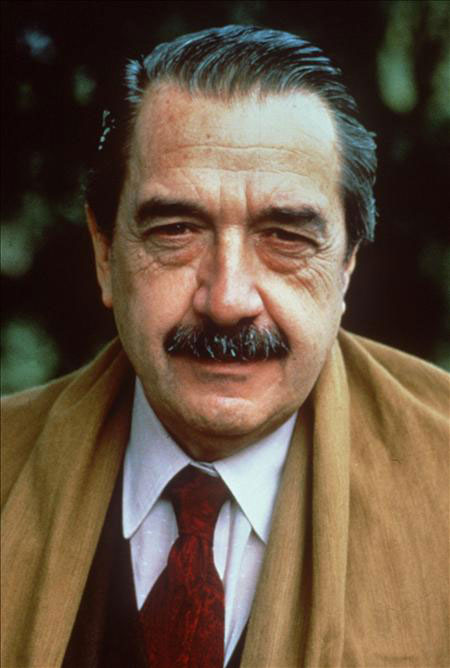

- President of Argentina Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín, 1927

PAGE SPONSOR

Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín (March 12, 1927 – March 31, 2009) was an Argentine lawyer, politician and statesman, who served as the President of Argentina from December 10, 1983, to July 8, 1989. Alfonsín was the first democratically elected president of Argentina following the military government known as the National Reorganization Process. He was awarded the Prince of Asturias Award for International Cooperation in 1985, among numerous other such recognitions.

Alfonsín was born in the city of Chascomús, in eastern Buenos Aires Province, to Raúl Serafín Alfonsín and Ana María Foulkes and raised in the Roman Catholic faith. Following his elementary schooling he took up studies at the General San Martín Military Academy, where he graduated after five years as a second lieutenant. He became affiliated with the centrist Radical Civic Union (UCR) in 1945 while taking an active role in the reform group, Intransigent Renewal Movement. He enrolled at the University of Buenos Aires Law School, from where he graduated in 1950 and returned to Chascomús as an attorney, marrying María Lorenza Barrenechea, the same year.

Alfonsín founded a local newspaper (El Imparcial) and was elected to the city council in 1951. Running as a UCR candidate for a seat in the Chamber of Deputies (the lower house of the Argentine Congress) later that year, he lost to an opponent supported by the country's newly elected populist leader, Juan Perón.

His periodical's opposition to the increasingly intolerant Perón

led to Alfonsín's incarceration in 1953. A violent September

1955 coup d'état (the self-styled Revolución Libertadora)

brought Perón's reign to an end, however, and the resulting ban

of Peronist political activity returned the UCR to its role as

Argentina's most important political party. He was elected to the Buenos Aires provincial legislature in 1958 on the UCRP ticket, a faction of the UCR slightly to the right of the winners of the 1958 election, the UCRI. Alfonsín was elected to the Chamber of Deputies in 1963, becoming one of President Arturo Illia's most steadfast supporters in Congress. He lost his seat when a military

coup removed Illia from office in 1966. Developing differences with the

party's moderately conservative leader, Ricardo Balbín, Alfonsín announced the formation of a Movement for Renewal and Change within the UCR in 1971. He stood for the UCR's nomination for the 1973 presidential election with Conrado Storani as his running mate, but lost to Balbín, who was in turn defeated by Perón's Justicialist Party. Argentina's

return to democracy in 1973 did not improve the country's difficult

political rights climate. An increasingly violent conflict between

far-left and far-right groups led to a succession of repressive

measures, mostly against the former. Amid spiraling violence in

December 1975, Alfonsín helped establish the Permanent Assembly for Human Rights. The March 1976 coup against the hapless President Isabel Perón did

not lead to the Permanent Assembly's closure and, instead, prompted its

affiliated lawyers, including Alfonsín, to lend their services

to the growing ranks of friends and relatives of the disappeared,

arguably risking their lives to do so. Alfonsín was among the

few prominent Argentine political figures to vocally oppose President Leopoldo Galtieri's April 1982 landings on the Falkland Islands. The 1981 collapse of conservative economist José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz's free trade and deregulatory policies and the defeat in the Falklands War, among other reasons, led the National Reorganization Process to seek a "democratic exit" in 1983, and new general elections were held on October 30. Alfonsín, who had been elected leader of the party in July that year, defeated Justicialist Party candidate Ítalo Lúder by 12 points, carrying a majority in the Chamber of Deputies and, though garnering only 18 of 46 seats in the Senate and 7 of 22 governors, the UCR's Alejandro Armendáriz scored an upset victory in Buenos Aires Province, home to one in three Argentines. Alfonsín persuaded President Reynaldo Bignone to advance the inaugural three months and he took office on December 10.

Chief

among Alfonsín's full platter of inherited problems was an

economic depression stemming from the 1981-82 financial collapse and

its resulting US$43 billion foreign debt, which demanded interest

payments that, alone, swallowed all of Argentina's US$3 billion trade

surplus. The economy had recovered modestly in 1983 as a result of

Bignone's lifting of wage freezes and crushing interest rates imposed

by the Central Bank's "Circular 1050;" but inflation raged at 400%, GDP

per capita remained at its lowest level since 1968 and fixed investment, 40% lower than in 1980. Naming a generally center-left cabinet led by Foreign Minister Dante Caputo and Economy Minister Bernardo Grinspun (his

campaign manager), Alfonsín began his administration with high

approval ratings and with the fulfillment of campaign promises such as

the inaugural of a nutritional assistance program for the 27% of

Argentines under the poverty line at the time, as well as the recission

of Bignone's April 1983 blanket amnesty for those guilty of human rights abuses and his September decree authorizing warrantless wiretapping. Defense Minister Raúl Borrás advised Alfonsín to remove Fabricaciones Militares, then Argentina's leading defense contractor,

from the Armed Forces' control, ordering the retirement of 70 generals

and admirals known for their opposition to the transfer of the

lucrative contractor. Appointing renowned playwright Carlos Gorostiza as Secretary of Culture and exiled computer scientist Dr. Manuel Sadosky as

Secretary of Science and Technology, hundreds of artists and scientists

returned to Argentina during 1984. Gorostiza abolished the infamous

National Film Rating Entity, helping lead to a doubling in film and

theatre production. The harrowing La historia oficial (The Official Story) was released in April 1985 and became the first Argentine film to secure an Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. Alfonsín created the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP) to document their human rights abuses. Led by renowned novelist Ernesto Sábato,

the CONADEP documented 8,960 forced disappearances and presented the

President with its findings on September 20. The report drew mixed

reactions, however, as its stated total of victims fell short of Amnesty International's estimate of 16,000 and of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo's estimate of 30,000. Alfonsín had leading members of leftist groups prosecuted early on, leading to jail sentences for, among others, Montoneros leader Mario Firmenich, though in May 1984 he pardoned former President Isabel Perón for her prominent role in the early stages of the Dirty War against dissidents and for her alleged embezzlement of public funds. His January introduction of legislation providing for the secret ballot labor union elections led to massive opposition by the CGT, Argentina's largest, and handed his administration its first defeat when the Senate struck it down in February by one vote. Relations with the United States suffered when Alfonsín terminated the previous regime's support for the Contras, and two meetings with U.S. President Ronald Reagan failed

to ease Reagan's opposition to economic concessions towards Argentina.

Alfonsín did, however, initiate the first diplomatic contact

with the United Kingdom since the Falklands War two years earlier, resulting in the lifting of British trade sanctions. Proposing a Treaty with Chile ending a border dispute over the Beagle Channel, he put the issue before voters in a November 25, 1984, referendum and won its approval with 82%. Inheriting a foreign debt crisis exacerbated

by high global interest rates, Alfonsín had to also contend with

shattered business confidence and record budget deficits. GDP grew by a

modest 2% in 1984, though fixed investment continued to decline and inflation rose to 700%. Losses among the panoply of State enterprises,

service on the public debt and growing tax evasion left the federal

budget with a US$10 billion shortfall in 1984 (13% of GDP). Unable to

finance it, the Central Bank of Argentina "printed"

money and inflation, which galloped at around 18% a month at the end of

the dictatorship, rose to 30% in June 1985 (the world's highest, at the

time). Attempting to control record inflation (prices had risen

twelve-fold in a year), his new Minister of the Economy, Juan Sourrouille, launched the Austral Plan, by which prices were frozen and the existing currency, the peso argentino, was replaced by the Argentine austral at 1,000 to one. Sharp

budget cuts were enacted, particularly in military spending which,

including cutbacks in 1984, was slashed to around half of its 1983

level. Responding to financial sector concerns, it also introduced a

mechanism called desagio, by which debtors whose installments were based on much higher built-in inflation would

received a temporary discount compensating for the sudden drop in

inflation and interest rates; indeed, inflation (30% in June) plummeted

to 2% a month for the remainder of 1985. The fiscal deficit fell by

two-thirds in 1985, helping pave the way for the first meaningful debt rescheduling since

the advent of the crisis four years earlier. Sharp cuts in military

spending also fed growing discontent in the military, and a number of

bomb threats and acts of sabotage at numerous military bases were

blamed on hard-line officers, chiefly former 1st Army Corps head Gen. Guillermo Suárez Mason, who fled to Miami following an October arrest order. Unable to persuade the military to court martial officers guilty of Dirty War abuses, Alfonsín sponsored the Trial of the Juntas, whose first hearing began at the Supreme Court on April 22, 1985. Prosecuting some of the top members of the previous military regime for crimes committed during the Dirty War,

the trial became the focus of sudden international attention and, on

December 9, the tribunal handed down life sentences against former

President Jorge Videla and former Navy Chief Emilio Massera, as well as 17-year sentences against three others. For these accomplishments, Alfonsín was awarded the first Prize For Freedom of the Liberal International and the Human Rights Prize by the Council of Europe, never before awarded to an individual. Four defendants were acquitted, however, notably former President Leopoldo Galtieri,

though he and two others were court-martialed in May 1986 for

malfeasance during the Falklands War, receiving 12-year prison

sentences. These developments contributed to a strong showing by the UCR in the November 1985 legislative elections.

They gained one seat in the Lower House of Congress and would control

130 of the 254 seats. The Justicialists lost eight seats (leaving 103)

and smaller, provincial parties made up the difference. Alfonsín

surprised observers in April 1986 by announcing the creation of a panel

entrusted to plan the transfer of the nation's capital to Viedma, a small coastal city 800 km (500 mi) south of Buenos Aires. His proposals boldly called for constitutional amendments creating a Parliamentary system, including a Prime Minister, and were well received by the Lower House, though it encountered strong opposition in the Senate. Economic concerns continued to dominate the national discourse, and the sharp fall in global commodity prices in

1986 stymied hopes for lasting financial stability. The nation's record

US$4.5 billion trade surplus was cut in half and inflation, which was

targeted for 28% in the calendar year, had declined to 50% in the

twelve months to June 1986 (compared to 1,130% to June 1985); though it

soon began to rise, exceeding 80% for the year. GDP, which had fallen

by 5% in 1985, recovered by 7% in 1986, led by a rise in machinery

purchases and consumer spending. Repeated

wage freezes ordered by Economy Minister Sorouille, however, led to an

erosion in real wages of about 20% during the Austral Plan's first

year, triggering seven general strikes by the CGT during the same

period. The President's August appointment of a conservative economist, José Luis Machinea, as President of the Central Bank pleased

the financial sector; but did little to stymie continuing capital

flight. Affluent Argentines were believed to hold over US$50 billion in

overseas deposits, by then. Alfonsín stepped up his itinerary of state visits abroad, securing a number of trade deals. The

President's international esteem for his human rights record suffered

in December 1986, when, on his initiative Congress passed the Full Stop Law, which limited the civil trials against roughly 300 officers implicated in the Dirty War to

those indicted within 60 days of the law's passage, a tall order given

the reluctance of many victims and witnesses to testify. Despite these

concessions, a group identified as Carapintadas ("painted faces," from their use of camouflage paint) loyal to Army Major Aldo Rico, staged a mutiny of the important Army training base of Campo de Mayo and near Córdoba during

the long weekend of Easter in 1987. Negotiating in person with the

rebels, who objected to ongoing civil trials but enjoyed little support

elsewhere in the Armed Forces, Alfonsín secured their surrender. Returning to the Casa Rosada, where an anxious population was waiting for news, he announced: La casa está en orden y no hay sangre en Argentina. ¡Felices pascuas! ("The house is in order and there's no blood in Argentina. Happy Easter!"), to signify the end of the crisis. His subsequent appointment of General Dante Caridi as Army Chief of Staff further strained relations with the military and in June, Congress passed Alfonsín's Law of Due Obedience, granting immunity to officers implicated in crimes against humanity on

the basis of "due obedience." This law, condemned by Amnesty

International, among others, effectively halted most remaining

prosecutions of Dirty War criminals. The climate of tension between

those on either side of the issue was aggravated by the suspicious

death in 1986 of Defense Minister Roque Carranza while in the Campo de Mayo military base and by the September 1987 discovery of the body of prominent banker Osvaldo Sivak, the victim of a police orchestrated ransom kidnapping netting over a million US dollars. Amid this political turn to the right, Alfonsín did manage the passage of the legalization of divorce,

helping resolve the legal status of 3 million adults (1 in 6) who were

separated from their spouse. He also passed the Antidiscrimination Law

of 1987, a bill supported by Argentina's sizable Jewish and Gypsy communities. He was awarded the Moisés (Moses) Prize by the Argentine Jewish community for the accomplishment. A

severe drought early in 1987 led to a new decline in exports, which

reached their lowest level in a decade, nearly cancelling the vital

trade surplus and leaving a US$6 billion current account deficit. The problem and the efforts of Alfonsín's debt negotiator, Daniel Marx,

helped secure the record rescheduling of US$19 billion in foreign

public debt (a third of the total); but speculators' concerns led to a

sudden fall in the value of the austral,

which lost half its value between June and October. As most Argentine

wholesalers accepted only U.S. dollars at the time, this inevitably led

to higher inflation, which leapt from 5% monthly in the first half of

1987 to 20% in October. Unimpressed by Alfonsín's appointment of

a Labor Minister from within the CGT's ranks, their leader, Saúl

Ubaldini, called two more general strikes during the year (hundreds of

smaller, sectorial strikes erupted, as well). A positive rapport between Alfonsín and the new, democratically elected President of Brazil, José Sarney, helped lead to initial agreements for a common market between the two nations and Uruguay in January 1988. Meeting in the Uruguayan resort of Punta del Este, they agreed to subsidize intra-regional exports with a special currency for the purpose (the Gaucho). A new Minister of Public Works, Rodolfo Terragno,

an academic with a long history in the UCR, prevailed on the

administration to allow a novel, if controversial, search for needed

foreign exchange: privatizations.

A number of factories and rail lines were offered for sale and, in

September 1987, the effort yielded its first results with the sale of Austral Airlines, a domestic carrier. Subsequent instability and the fallout from the Wall Street Crash of 1987 dampened

further deals, however, and left Sorouille little choice but to raise

taxes. GDP managed a 3% rise in 1987, led by higher construction

spending, though inflation rose to 175% and real wages declined around

10%, leaving them lower than they were in 1983. This turn for the worse helped to a significant setback for Alfonsín's UCR in local and legislative elections in September 1987.

The UCR lost 13 seats in Congress (leaving 117). Though still enjoying

a 12-seat advantage over Justicialists, this deprived the UCR of its

absolute majority in the Lower House and, five seats short of a

majority in the Senate, this effectively suspended much of the UCR's

legislative agenda, particularly the planned transfer of the capital to

the Patagonia region.

UCR governors fared even worse: the 1987 mid-term election left only

two, toppling, among four others, Governor Armendáriz of the

paramount Province of Buenos Aires. Ongoing military discontent reached

a flash point when Major Aldo Rico, the instigator of the Easter

Rebellion, escaped from house arrest, promptly organizing a second

mutiny in January 1988, though the mutiny was, again, quickly subdued.

The resulting tension and continuing stagflation set the stage for

Alfonsín's announcement that elections, scheduled for October

1989, would be moved up five months earlier. The

campaign made strange bedfellows of Alfonsín and the CGT during

the May 1988 Justicialist Party convention. The CGT was adverse to the

frontrunner for the nomination, Buenos Aires Governor Antonio Cafiero.

The President, in turn, preferred to see his struggling UCR (14 points

behind in the polls) matched against Cafiero's rival, a little known

and flamboyant governor of one of the nation's smallest provinces; in

an upset, Governor Carlos Menem was nominated the Justicialist Party's standard bearer. The UCR made a safe choice: Eduardo Angeloz,

the centrist governor of Córdoba Province (Argentina's

second-largest) and the most prominent UCR figure not closely tied to

the unpopular Alfonsín. The

Austral Plan continued to disintegrate as the economy slipped back into

recession. Inflation continued at 15-20% a month and in August, reached

27%. Foreign debt installments fell into arrears in April when

Alfonsín ordered the Central Bank to curtail payments.

Coinciding with the Southern Hemisphere's change of seasons, Economy

Minister Sorouille announced a Plan Primavera ("Springtime

Plan") on August 3, whose centerpiece was a price truce agreed on with

53 leading wholesalers. The plan also included a fresh wage freeze,

however, triggering a September 9 general strike by the CGT that turned

violent when police repressed demonstrators at the Plaza de Mayo. Violent and white collar crime were of increasing concern among the public and, though the judicial system scored a victory when Banco Alas executives were convicted the same day for fraud committed against the Central Bank totalling US$110 million, their receiving a suspended sentence in

exchange for the return of half the funds and the subsequent discovery

of a sub-rosa "parallel customs" operated by National Customs Director Juan Carlos Delconte cast

serious doubts on Alfonsín's commitment against large-scale

corruption, which had become endemic to Argentine government and

business during the 1970s. Alfonsín obtained INTERPOL's cooperation in extraditing fugitive Army Corps leader Gen. Guillermo Suárez Mason (a leading Dirty War perpetrator whose control over YPF nearly bankrupted the state oil concern in 1983) and Argentine Anticommunist Alliance mastermind José López Rega, who were found in their Miami exile

and returned to stand trial in 1987. The President's relationship with

the military remained tenuous. Continuing military budget cuts and

opposition to democratic rule led the extremist Carapintadas to

stage a third mutiny on December 1, receiving support from disaffected

members of the Coast Guard, among others. The impasse lasted six days,

resulting in the arrest of their leader, Col. Mohamed Alí Seineldín, an Army officer with a long history of violence and anti-semitism.

In the interest of compromise, Alfonsín announced a modest

military budget increase and the dismissal of the moderate Gen. Dante

Caridi as Army Chief of Staff. A January 23, 1989 attack on the Regiment of La Tablada by

a leftist armed organization led to 39 deaths and tested Alfonsín's improved rapport with the military, which was

consequently given wide latitude to prosecute the matter, leading to

the alleged torture of a number of the conspirators. The

economy had benefited only modestly from lower inflation, which had

fallen from 27% in August to 5-10% monthly for the rest of 1988. Owing

to the mid-year recession, GDP fell 2% in 1988 and inflation rose to

380% while real wages continued to slide. Exports

did recover and the trade surplus rose to nearly US$4 billion. The

Springtime Plan, however, increasingly depended on its reserves to

shore up the austral, whose stability guaranteed more moderate

inflation. In so doing, the Central Bank shed almost all its US$3

billion in reserves and, in heavy trading on "Black Tuesday," February

7, 1989, the U.S. dollar gained around 40% against the austral. The

sudden drop in the austral's value threatened the nation's tenuous

financial stability and, later that month, the World Bank recalled a

large tranche of a loan package agreed on in 1988, sending the austral

into a tailspin: trading at 17 to the dollar in January, the dollar

quoted at over 100 australes by election day, May 14. Inflation, which

had been held below 10% a month as late as February, rose to 78.5% in

May, shattering records and leading to a landslide victory for the

Justicialist candidate, Carlos Menem. Polling revealed that economic

anxieties were paramount among two-thirds of voters and Menem won in 19

of 22 provinces, while losing in the traditionally anti-Peronist

Federal District (Buenos Aires). The

nation's finances did not stabilize after the election, as hoped. The

dollar doubled in value that next week, alone and, on May 29, riots and looting broke out in the poorer outskirts of a number of cities, particularly Rosario.

Inflation continued its dizzying rise: 114% a month in June and 197% in

July. Income poverty leapt from around 30% to 47% during the debacle and the economy shrank by 7% in 1989, pushing per capita GDP to its lowest level since 1964. Having

declared his intention to stay on until inaugural day, December 10,

these events and spiraling financial chaos led Alfonsín to

transfer power to President-elect Menem on July 8. Alfonsín was forced to step down as President of the UCR following that party's defeat at the September 1991 midterm elections.

He defeated former Governor Armendáriz for the post in 1993,

however, on anticipation of a power-sharing deal with the then-popular

President Carlos Menem. Alfonsín and Menem signed the November

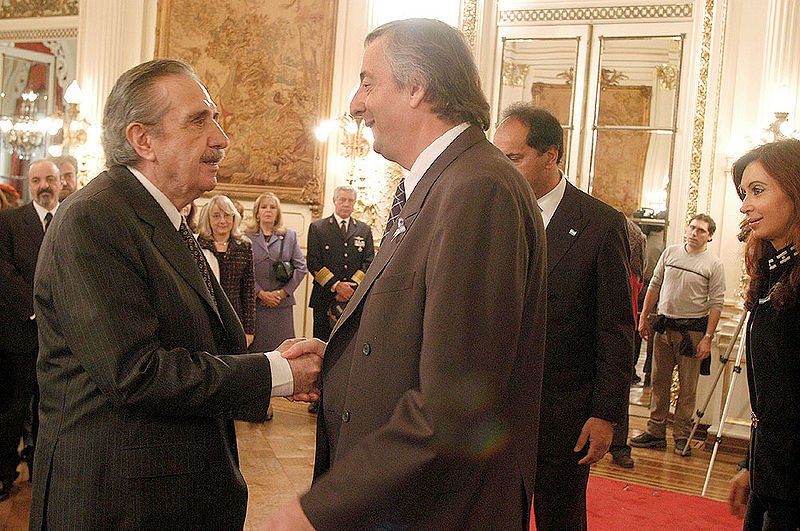

1993 Olivos Pact, through which the two largest Argentine parties agreed to support a constitutional reform which (among other things) provided the party in opposition increased representation in the Senate and paved the way for President Menem's reelection. He resigned as leader of the UCR after their poor performance in the 1995 elections; but he continued to be an important figure within the party, negotiating a successful alliance with the center-left Frepaso (who garnered 30% in 1995), ahead of the 1997 midterm elections. Alfonsín suffered a serious automobile accident en route to a campaign event in June 1999, though he recovered quickly. He was returned as leader of the UCR in October 2000 amid growing difficulties surrounding President Fernando de la Rúa, a prominent UCR figure elected in 1999 on the Alliance ticket with the center-left Frepaso. He

was elected Senator for Buenos Aires Province in October 2001, but

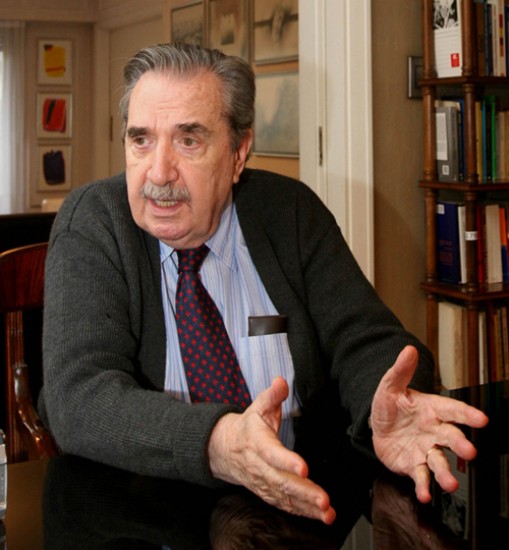

health problems led him to step down after a year, to be replaced by Diana Conti. In 2006, Alfonsín supported a faction of the UCR that favoured the idea of carrying an independent candidate for the 2007 presidential elections. The UCR, instead of fielding its own candidate, endorsed Roberto Lavagna, a center-left economist who presided over the dramatic recovery in the Argentine economy from 2002 until he parted ways with President Néstor Kirchner in December 2005. Unable to sway enough disaffected Kirchner supporters, Lavagna garnered third place. Alfonsín was a member of the Club of Madrid and was honored by President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner with a bust of his likeness at the Casa Rosada on October 1, 2008. He was the only Argentine president to receive that homage during his lifetime. Alfonsín died on 31 March 2009, at the age of 82, after being diagnosed a year before with lung cancer and

enduring a surgery intervention in the United States. He died

peacefully in his home, surrounded by his family. Argentina declared

three days of national mourning following his death through 2 April

2009. He was buried in La Recoleta Cemetery in Buenos Aires. Thousands of Argentines mourned his death by crowding Callao Avenue in

Buenos Aires, waiting to accompany Dr. Alfonsín to his final

resting place. The media captured the popular sentiment by pointing out

that "the Argentine people wants to send a message: it is time to

return to the values taught to us by Dr. Alfonsín: honesty, hard

work, justice and equality for all." Some

critics point out that he failed to stave off a deep economic crisis

but his political achievements were of such magnitude, that they were

summed up by current President Cristina Kirchner, when she unveiled his

bust in 2008: "Whether you like it or not, you are a symbol of the

return of democracy", she said. President

Alfonsín may be remembered by the Argentine people as a unique

man in the country's political history: one that wasn't afraid to

listen to the voice of opposition, one who welcomed political debate in

good faith, and one that inspired generations of citizens to go out and

vote, to make their voices heard, and to work hard for the preservation

of democracy.