<Back to Index>

- Mathematician George David Birkhoff, 1884

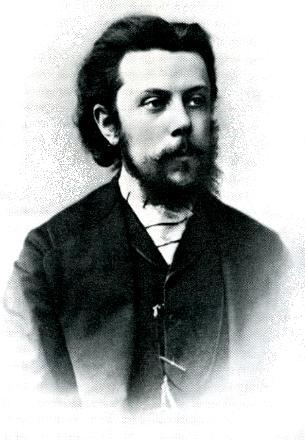

- Composer Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, 1839

- President of Bolivia Hernán Siles Zuazo, 1914

PAGE SPONSOR

Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky (Russian: Модест Петрович Мусоргский) (March 21 [O.S. March 9], 1839 – March 28 [O.S. March 16], 1881), one of the Russian composers known as the Five, was an innovator of Russian music in the romantic period. He strove to achieve a uniquely Russian musical identity, often in deliberate defiance of the established conventions of Western music.

Many of his works were inspired by Russian history, Russian folklore, and other nationalist themes, including the opera Boris Godunov, the orchestral tone poem Night on Bald Mountain, and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition.

For

many years Mussorgsky's works were mainly known in versions revised or

completed by other composers. Many of his most important compositions

have recently come into their own in their original forms, and some of

the original scores are now also available. Mussorgsky was born in Karevo, Russia, in the province of Pskov, 400 kilometers (249 mi) south-south-east of Saint Petersburg. His wealthy and land-owning family, the noble family of Mussorgsky, is reputedly descended from the first Ruthenian ruler, Rurik, through the sovereign princes of Smolensk.

At age six Mussorgsky began receiving piano lessons from his mother,

herself a trained pianist. His progress was sufficiently rapid that

three years later he was able to perform a John Field concerto and works by Franz Liszt for family and friends. At 10, he and his brother were taken to Saint Petersburg to study at the elite Peterschule (St. Peter's School). While there, Modest studied the piano with the noted Anton Herke. In 1852, the 12 year old Mussorgsky published a piano piece titled "Porte-enseigne Polka" at his father's expense. Mussorgsky's

parents planned the move to Saint Petersburg so that both their sons

would renew the family tradition of military service. To

this end, Mussorgsky entered the Cadet School of the Guards at age 13.

Sharp controversy had arisen over the educational attitudes at the time

of both this institute and its director, a General Sutgof. All agreed the Cadet School could be a brutal place, especially for new recruits. More tellingly for Mussorgsky, it was likely where he began his eventual path to alcoholism. According

to a former student, singer and composer Nikolai Kompaneisky, Sutgof

"was proud when a cadet returned from leave drunk with champagne." Music

remained important to him, however. Sutgof's daughter was also a pupil

of Herke, and Mussorgsky was allowed to attend lessons with her. His skills as a pianist made him much in demand by fellow-cadets; for them he would play dances interspersed with his own improvisations. In

1856 Mussorgsky – who had developed a strong interest in history and

studied German philosophy – successfully graduated from the Cadet School.

Following family tradition he received a commission with the Preobrazhensky Regiment, the foremost regiment of the Russian Imperial Guard. In October 1856 the 17-year-old Mussorgsky met the 22-year-old Alexander Borodin while both men served at a military hospital in Saint Petersburg. The two were soon on good terms. Borodin later remembered, "His

little uniform was spic and span, close-fitting, his feet turned

outwards, his hair smoothed down and greased, his nails perfectly cut,

his hands well groomed like a lord's. His manners were elegant,

aristocratic: his speech likewise, delivered through somewhat clenched

teeth, interspersed with French phrases, rather precious. There was a

touch — though very moderate — of foppishness.

His politeness and good manners were exceptional. The ladies made a

fuss of him. He sat at the piano and, throwing up his hands

coquettishly, played with extreme sweetness and grace (etc) extracts

from Trovatore, Traviata,

and so on, and around him buzzed in chorus: "Charmant,

délicieux!" and suchlike. I met Modest Petrovich three or four

times at Popov's in this way, both on duty and at the hospital." More portentous was Mussorgsky's introduction that winter to Alexander Dargomyzhsky, at that time the most important Russian composer after Mikhail Glinka.

Dargomyzhsky was impressed with Mussorgsky's pianism. As a result,

Mussorgsky became a fixture at Dargomyzhsky's soirées. There,

critic Vladimir Stasov later recalled, he began "his true musical life." Over

the next two years at Dargomyzhsky's, Mussorgsky met several figures of

importance in Russia's cultural life, among them Stasov, César Cui (a fellow officer), and Mily Balakirev.

Balakirev had an especially strong impact. Within days he took it upon

himself to help shape Mussorgsky's fate as a composer. He recalled to

Stasov, "Because I am not a theorist, I could not teach him harmony

(as, for instance Rimsky-Korsakov now teaches it) ... [but] I explained to him the form of compositions, and to do this we played through both Beethoven symphonies [as piano duets] and much else (Schumann, Schubert, Glinka, and others), analyzing the form." Up

to this point Mussorgsky had known nothing but piano music; his

knowledge of more radical recent music was virtually non-existent.

Balakirev started filling these gaps in Mussorgsky's knowledge. In

1858, within a few months of beginning his studies with Balakirev,

Mussorgsky resigned his commission to devote himself entirely to music. He

also suffered a painful crisis at this time. This may have had a

spiritual component (in a letter to Balakirev the young man referred to

"mysticism and cynical thoughts about the Deity"), but its exact nature

will probably never be known. In 1859, the 20-year-old gained valuable

theatrical experience by assisting in a production of Glinka's opera A Life for the Tsar on the Glebovo estate of a former singer and her wealthy husband; he also met Lyadov and enjoyed a formative visit to Moscow – after which he professed a love of "everything Russian". In

spite of this epiphany, Mussorgsky's music still leaned more toward

foreign models; a four-hand piano sonata which he produced in 1860

contains his only movement in sonata form. Nor is any 'nationalistic' impulse easily discernible in the incidental music for Serov's play Oedipus in Athens, on which he worked between the ages of 19 and 22 (and then abandoned unfinished), or in the Intermezzo in modo classico for

piano solo (revised and orchestrated in 1867). The latter was the only

important piece he composed between December 1860 and August 1863: the

reasons for this probably lie in the painful re-emergence of his

subjective crisis in 1860 and the purely objective difficulties which

resulted from the emancipation of the serfs the

following year – as a result of which the family was deprived of half

its estate, and Mussorgsky had to spend a good deal of time in Karevo

unsuccessfully attempting to stave off their looming impoverishment. By

this time, Mussorgsky had freed himself from the influence of Balakirev

and was largely teaching himself. In 1863 he began an opera – Salammbô –

on which he worked between 1863 and 1866 before losing interest in the

project. During this period he had returned to Saint Petersburg and was

supporting himself as a low-grade civil servant while living in a

six man 'commune'. In a heady artistic and intellectual atmosphere, he

read and discussed a wide range of modern artistic and scientific ideas

– including those of the provocative writer Chernyshevsky,

known for the bold assertion that, in art, "form and content are

opposites". Under such influences he came more and more to embrace the

ideal of artistic 'realism' and all that it entailed, whether this

concerned the responsibility to depict life 'as it is truly lived'; the

preoccupation with the lower strata of society; or the rejection of

repeating, symmetrical musical forms as insufficiently true to the

unrepeating, unpredictable course of 'real life'. 'Real

life' affected Mussorgsky painfully in 1865, when his mother died; it

was at this point that the composer had his first serious bout of either alcoholism or dipsomania.

The 26 year old was, however, on the point of writing his first

'realistic' songs (including 'Hopak' and 'Darling Savishna', both of

them composed in 1866 and among his first 'real' publications the

following year). 1867 was also the year in which he finished the

original orchestral version of his Night on Bald Mountain (which,

however, Balakirev criticised and refused to conduct, with the result

that it was never performed during Mussorgsky's lifetime).

Mussorgsky's

career as a civil servant was by no means stable or secure: though he

was assigned to various posts and even received a promotion in these

early years, in 1867 he was declared 'supernumerary' – remaining 'in

service', but receiving no wages. Decisive developments were occurring

in his artistic life, however. Although it was in 1867 that Stasov

first referred to the 'kuchka' ('The Five') of Russian composers loosely grouped around Balakirev,

Mussorgsky was by then ceasing to seek Balakirev's approval and was

moving closer to the older Alexander Dargomyzhsky . Since 1866 Dargomïzhsky had been working on his opera The Stone Guest, a version of the Don Juan story with a Pushkin text

that he declared would be set "just as it stands, so that the inner

truth of the text should not be distorted", and in a manner that

abolished the 'unrealistic' division between aria and recitative in favour of a continuous mode of syllabic but lyrically heightened declamation somewhere between the two. Under the influence of this work (and the ideas of Georg Gottfried Gervinus,

according to whom "the highest natural object of musical imitation is

emotion, and the method of imitating emotion is to mimic speech"),

Mussorgsky in 1868 rapidly set the first eleven scenes of Gogol's Zhenitba (The Marriage),

with his priority being to render into music the natural accents and

patterns of the play's naturalistic and deliberately humdrum dialogue.

This work marked an extreme position in Mussorgsky's pursuit of

naturalistic word-setting: he abandoned it unorchestrated after

reaching the end of his 'Act 1', and though its characteristically

'Mussorgskyian' declamation is to be heard in all his later vocal

music, the naturalistic mode of vocal writing more and more became

merely one expressive element among many. A few months after abandoning Zhenitba, the 29 year old Mussorgsky was encouraged to write an opera on the story of Boris Godunov. This he did, assembling and shaping a text from Pushkin's play and Karamzin's

history. He completed the large-scale score the following year while

living with friends and working for the Forestry Department. In 1871,

however, the finished opera was rejected for theatrical performance,

apparently because of its lack of any 'prima donna'

role. Mussorgsky set to work producing a revised and enlarged 'second

version'. During the next year, which he spent sharing rooms with

Rimsky-Korsakov, he made changes that went beyond those requested by

the theatre. In this version the opera was accepted, probably in May

1872, and three excerpts were staged at the Mariinsky Theatre in 1873. It is often asserted that in 1872 the opera was rejected a second time, but no specific evidence for this exists. By the time of the first production of Boris Godunov in February 1874, Mussorgsky had taken part in the ill-fated Mlada project (in the course of which he had made a choral version of his Night on Bald Mountain) and had begun Khovanshchina.

Though far from being a critical success - and in spite of receiving

only a dozen or so performances - the popular reaction in favour of Boris made this the peak of Mussorgsky's career. From

this peak a pattern of decline becomes increasingly apparent. Already

the Balakirev circle was disintegrating. Mussorgsky was especially

bitter about this. He wrote to Vladimir Stasov, "[T]he mighty Koocha has degenerated into soulless traitors.". In

drifting away from his old friends, Mussorgsky had been seen to fall

victim to 'fits of madness' that could well have been

alcoholism related. His friend Viktor Hartmann had died, and his relative and recent roommate Arseny Golenishchev-Kutuzov (who furnished the poems for the song-cycle Sunless and would go on to provide those for the Songs and Dances of Death) had moved away to get married. While

alcoholism was Mussorgsky's personal weakness, it was also a behavior

pattern considered typical for those of Mussorgsky's generation who

wanted to oppose the establishment and protest through extreme forms of

behavior. One

contemporary notes, "an intense worship of Bacchus was considered to be

almost obligatory for a writer of that period. It was a showing off, a

'pose,' for the best people of the [eighteen-]sixties." Another writes,

"Talented people in Russia who love the simple folk cannot but drink." Mussorgsky

spent day and night in a Saint Petersburg tavern of low repute, the

Maly Yaroslavets, accompanied by other bohemian dropouts. He and his

fellow drinkers idealized their alcoholism, perhaps seeing it as

ethical and aesthetic opposition. This bravado, however, led to little

more than isolation and eventual self-destruction. For a time Mussorgsky was able to maintain his creative output: his compositions from 1874 include Sunless, the Khovanschina Prelude, and the piano suite Pictures at an Exhibition (in memory of Hartmann); he also began work on another opera based on Gogol, The Fair at Sorochyntsi (for which he produced another choral version of Night on Bald Mountain). In

the years that followed, Mussorgsky's decline became increasingly

steep. Although now part of a new circle of eminent personages that

included singers, medical men and actors, he was increasingly unable to

resist drinking, and a succession of deaths among his closest

associates caused him great pain. At times, however, his alcoholism

would seem to be in check, and among the most powerful works composed

during his last 6 years are the four Songs and Dances of Death.

His civil service career was made more precarious by his frequent

'illnesses' and absences, and he was fortunate to obtain a transfer to

a post (in the Office of Government Control) where his music-loving

superior treated him with great leniency – in 1879 even allowing him to

spend 3 months touring 12 cities as a singer's accompanist. The

decline could not be halted, however. In 1880 he was finally dismissed

from government service. Aware of his destitution, one group of friends

organised a stipend designed to support the completion of Khovanschina; another group organised a similar fund to pay him to complete The Fair at Sorochyntsi. However, neither work was completed (although Khovanschina, in piano score with only two numbers uncomposed, came close to being finished). In

early 1881 a desperate Mussorgsky declared to a friend that there was

'nothing left but begging', and suffered four seizures in rapid

succession. Though he found a comfortable room in a good hospital – and

for several weeks even appeared to be rallying – the situation was

hopeless. Repin painted

the famous red–nosed portrait in what were to be the last days of the

composer's life: a week after his 42nd birthday, he was dead. He was

interred at the Tikhvin Cemetery of the Alexander Nevsky Monastery in Saint Petersburg. Mussorgsky,

like others of 'The Five', was perceived as extremist by the Emperor

and much of his court. This may have been the reason Tsar Alexander III personally crossed off Boris Godunov from the list of proposed pieces for the Imperial Opera in 1888.