<Back to Index>

- Mathematician George David Birkhoff, 1884

- Composer Modest Petrovich Mussorgsky, 1839

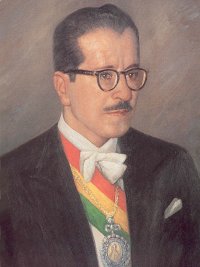

- President of Bolivia Hernán Siles Zuazo, 1914

PAGE SPONSOR

Hernán Siles Zuazo (March 21, 1914, Bolivia – August 6, 1996, Uruguay) was a politician from Bolivia. He served as his country's constitutionally elected president twice, from 1956 to 1960 and again from 1982 to 1985.

Born in a privileged family, Hernán Siles was the son of a former president of Bolivia, Hernando Siles. After attaining a law degree in the 1930s, he dedicated himself to politics. Gravitating toward the reformist side of the political spectrum (even though his father had been one of the pillars of the Old Regime he aimed at transforming), he founded in 1941, along with Víctor Paz Estenssoro and others, the influential Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario, or MNR). The MNR participated in the 1943-46 progressive military administration of Gualberto Villarroel, but was forced from power due to U.S. pressure and also by Villarroel's overthrow in 1946. Paz Estenssoro ran in the 1951 elections with Siles as his vice-presidential running mate, and won the contest. However, the ultra-conservative government of Mamerto Urriolagoitia refused to recognize the results and instead turned over the presidency to the commander of the Bolivian army, general Hugo Ballivián. At that point the MNR party went underground and in April 1952 led the epoch-making National Revolution, aided by defections from the armed forces to the rebel cause (key among which was general Antonio Seleme). Siles played a major role in the bloody uprising, along with Juan Lechin, since the MNR chief Paz Estenssoro was at the time in exile in Argentina.

Having routed the loyalist military and toppled the Ballivián government, Siles served as provisional president from April 11, 1952 until April 16, 1952, when Paz returned from abroad. The 1951 electoral results were upheld, and Paz became constitutional president of Bolivia and Siles vice-president (1952-56). During the MNR's first 4 years in office, the government instituted far-reaching reforms, including the establishment of the universal vote, nationalization of the largest mining concerns in the country, and the adoption of a major land distribution program (agrarian reform). In 1956, Paz left office since the Bolivian Constitution forbade a sitting president from running for another consecutive term. Siles, his logical successor, easily won that year's electoral contest and became President of the Republic.

The first Siles' administration (1956-60) was considerably more contentious and difficult than Paz's had been. The MNR began to fragment along personal lines and due to growing disagreements over policy. Inflation soared, and the United States conditioned aid and further support on the adoption of an economic program of its own prescription (the so-called Eder Plan). Furthermore, it fell to Siles to tackle the difficult issue of disarming the militia members who had combatted in the 1952 Revolution and who had been for the most allowed to keep their weapons since. They had served as a useful counterbalance to the possibility of a conservative or military reassertion against the Revolution, but were by now serving the ambitions of the caudillo-like head of the Central Workers' Union, or COB, Juan Lechín. Meanwhile, the opposition party Falange Socialista Boliviana schemed to topple the MNR from power, creating a rather disproportionate repressive backlash that diminished the party's (and Siles') popularity.

When Siles' term was up in 1960, Paz Estenssoro once more ran for president and, upon being elected, appointed Siles Bolivian ambassador to Uruguay. In 1964, Siles broke with Paz over the latter's decision to amend the Constitution in order to become re-elected directly. At that point he formed the Movimiento Nacionalista Revolucionario de Izquierda (MNRI), beginning a steady drift toward the left. Originally Siles supported the November 1964 anti-MNR coup d'état — led by generals René Barrientos and Alfredo Ovando -- but was later exiled when it became apparent that the military intended to manipulate electoral results and perpetuate itself in power. For the most part, the armed forces remained in control of the Palacio Quemado from 1964 until 1982. In 1971, Siles opposed the right-wing coup of general Hugo Banzer, prompting an irreversible break with Paz, who had supported it.

After the 1978 democratic opening, Siles formed a grand alliance of the left with the Movimiento de Izquierda Revolucionaria, the Communist Party, and others. Together, they formed the Unidad Democrática y Popular (UDP), which triumphed in the 1978, 1979, and 1980 elections, mostly as a result of the serious erosion of support for Paz in the aftermath of his original acquiescence to the Banzer dictatorship. The 1978 election was annulled due to massive fraud in favor of the officialist military candidate, general Juan Pereda; the 1979 contest remained inconclusive because, no candidate having received the necessary 50% of the vote, Congress had to determine the president, and it could not agree on any one candidate. Finally, the popular Siles won again in 1980 and would have taken power, weren't for the bloody coup of July 17, 1980, which installed a reactionary (and cocaine tainted) dictatorship led by general Luis García Meza. At that point, Siles flew to exile, but returned in 1982, when the military's experiment had run its course and the Bolivian economy was on the verge of collapse.

With the military's reputation badly damaged by the excesses of the 1980-82 dictatorship, the only way out was a hasty retreat. In October 1982 the results of the 1980 elections were upheld to save the country the expense of yet another vote, and Siles was sworn in to his second term, with the MIR's Jaime Paz as his vice-president. The economic situation was dire indeed, and soon a galloping hyperinflationary process developed. Siles had great difficulty in controlling the situation, and in all fairness received scant support from the political parties or members of congress, most of whom were eager to flex their newly-acquired political muscles after so many years of authoritarianism. The unions, led by the old MNR firebrand Juan Lechín Oquendo paralyzed the government with constant strikes, and even the vice-president, Jaime Paz, deserted the sinking ship when Siles' popularity sank to an all-time low. The 1982-86 hyperinflation would end up being the fourth largest ever recorded in the world. Still, Siles refused to adopt extra-constitutional measures, preferring instead to consolidate the hard-earned Bolivian democracy regardless of the personal cost to him. He even went on a hunger strike as a desperate way to gain public sympathy. Finally, he agreed to shorten his own term and Congress moved the presidential election forward by a year.

One bright point in the Siles administration was the 1983 extradition to France of the Nazi war criminal Klaus Barbie, known as the Butcher of Lyon. He had been living in Bolivia since the late 1950s or early 1960s, after being smuggled out of Europe with the assistance of the United States, and was often employed by the 1964-82 dictatorships as an interrogation specialist. Following his extradition he was condemned for his crimes and died in a French prison.

By 1985, the government's impotence prompted Congress to call early elections, citing the fact that Siles had been originally elected five long years before. The MNR's Víctor Paz Estenssoro was elected president, and Siles left for Uruguay, a country where he had lived before in exile and for which he held special affection. He would die in Uruguay on August 1996 and the age of 82.