<Back to Index>

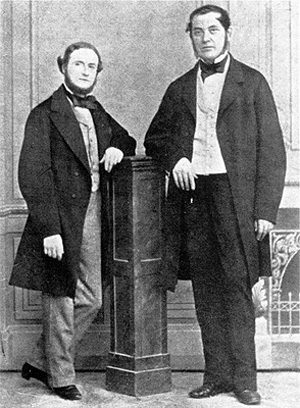

- Chemist Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen, 1811

- Art Critic and Founder of the Ballets Russes Sergei Pavlovich Diaghilev, 1872

- President of Dáil Éireann Arthur Griffith, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Robert Wilhelm Eberhard Bunsen (31 March 1811 – 16 August 1899) was a German chemist. He investigated emission spectra of heated elements, and with Gustav Kirchhoff discovered caesium (in 1860) and rubidium (in 1861). Bunsen developed several gas-analytical methods, was a pioneer in photochemistry, and did early work in the field of organoarsenic chemistry. With his laboratory assistant, Peter Desaga, he developed the Bunsen burner, an improvement on the laboratory burners then in use. The Bunsen-Kirchhoff Award for spectroscopy is named after Bunsen and his colleague, Gustav Kirchhoff.

Bunsen was born in Göttingen, Germany. He was the youngest of four sons of the University of Göttingen's chief librarian and professor of modern philology, Christian Bunsen (1770 – 1837). After attending school in Holzminden, in 1828 Bunsen matriculated at Göttingen and studied chemistry with Friedrich Stromeyer, obtaining the Ph.D. degree in 1831. In 1832 and 1833 he traveled in Germany, France, and Austria, where he met Friedrich Runge (who discovered aniline and in 1819 isolated caffeine), Justus von Liebig in Gießen, and Eilhard Mitscherlich in Bonn.

In 1833 Bunsen became a lecturer at Gottingen and began experimental studies of the (in)solubility of metal salts of arsenous acid. Today, his discovery of the use of iron oxide hydrate as a precipitating agent is still the best-known antidote against arsenic poisoning. In 1836, Bunsen succeeded Friedrich Wöhler at the Polytechnic School of Kassel. Bunsen taught there for three years, and then accepted an associate professorship at the University of Marburg, where he studied cacodyl derivatives. He was promoted to full professor in 1841.

Bunsen's work brought him quick and wide acclaim, partly because cacodyl, which is extremely toxic and undergoes spontaneous combustion in dry air, is so difficult to work with. Bunsen almost died from arsenic poisoning, and an explosion with cacodyl cost him sight in his right eye. In 1841, Bunsen created the Bunsen cell battery, using a carbon electrode instead of the expensive platinum electrode used in William Robert Grove's electrochemical cell. Early in 1851 he accepted a professorship at the University of Breslau, where he taught for three semesters.

In late 1852 Bunsen became the successor of Leopold Gmelin at the University of Heidelberg. There he used electrolysis to produce pure metals, such as chromium, magnesium, aluminium, manganese, sodium, barium, calcium and lithium. A long collaboration with Henry Enfield Roscoe began in 1852, in which they studied the photochemical formation of hydrogen chloride from hydrogen and chlorine.

Bunsen discontinued his work with Roscoe in 1859 and joined Gustav Kirchhoff to study emission spectra of heated elements, a research area called spectrum analysis. For this work, Bunsen and his laboratory assistant, Peter Desaga, had perfected a special gas burner by 1855, influenced by earlier models. The newer design of Bunsen and Desaga, which provided a very hot and clean flame, is now called simply the "Bunsen burner".

In 1860, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Bunsen

was one of the most universally admired scientists of his generation.

He was a master teacher, devoted to his students, and they were equally

devoted to him. At a time of vigorous and often caustic scientific

debates, Bunsen always conducted himself as a perfect gentleman,

maintaining his distance from theoretical disputes. He much preferred

to work quietly in his laboratory, regularly enriching his science with

useful discoveries. On a point of principle, he never took out a

patent, despite the fact that his new battery and new laboratory burner

would surely have brought him great wealth. When focused on a problem, Bunsen refused to be disturbed. An anecdote related by J. Norman Collie tells

how Bunsen was once engaged to be married, but on the marriage day, he

was found locked up in his laboratory. After he was found missing at

church, some friends came up and knocked on the door but he shouted "Go

away, I am busy". It appears that Bunsen never married. When Bunsen retired at the age of 78, he shifted his work solely to geology and mineralogy, an interest which he had pursued throughout his career. He died in Heidelberg, aged 88, and was buried there.