<Back to Index>

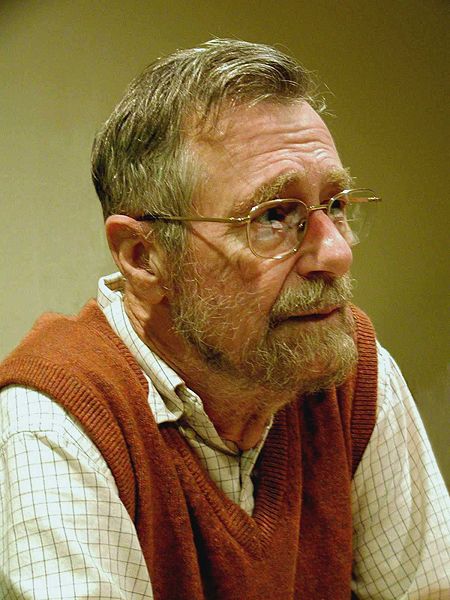

- Computer Scientist Edsger Wybe Dijkstra, 1930

- Painter Salvador Domingo Felipe Jacinto Dalí y Domènech, 1904

- Cavalry Captain Karl Friedrich Hieronymus, Freiherr von Münchhausen, 1720

PAGE SPONSOR

Edsger

Wybe Dijkstra (May

11, 1930 – August 6, 2002)

was

a Dutch computer

scientist. He received the 1972 Turing

Award for fundamental contributions to developing programming languages, and was

the Schlumberger Centennial Chair of Computer Sciences at The University

of

Texas at Austin from

1984

until 2000. Shortly

before his death in 2002, he received the ACM PODC Influential Paper

Award in distributed computing for his work on self-stabilization of program computation.

This annual award was renamed the Dijkstra

Prizethe following year, in his honour. Born in Rotterdam,

Netherlands, Dijkstra studied theoretical

physics at Leiden

University, but quickly realized he was more interested in computer

science. Originally employed by the Mathematisch

Centrum in

Amsterdam, he held a professorship at the Eindhoven

University

of Technology, worked as a research fellow for Burroughs

Corporation in the

early 1970s, and later held the Schlumberger Centennial Chair in

Computer Sciences at the University

of

Texas at Austin, in the United States. He retired in 2000. Among his

contributions to computer science are the shortest

path-algorithm,

also

known as Dijkstra's

algorithm; Reverse

Polish Notation and

related Shunting

yard

algorithm; the THE

multiprogramming

system, an important early example of structuring a system as a set of layers; Banker's

algorithm; and the semaphore construct for coordinating

multiple processors and programs. Another concept due to Dijkstra in

the field of distributed computing is that of self-stabilization – an alternative way to

ensure the reliability of the system. Dijkstra's algorithm is used in

SPF, Shortest

Path

First, which is used in the routing protocol OSPF, Open

Shortest

Path First. While he

had programmed extensively in machine code in the 1950s, he was known

for his low opinion of the GOTO statement

in computer

programming, writing a paper in 1965, and culminating in the 1968

article "A

Case

against the GO TO Statement", regarded as a major

step towards the widespread deprecation of the GOTO statement and its effective

replacement by structured control

constructs, such as the while

loop. This methodology was also called structured

programming, the title of his 1972 book, coauthored with C.A.R.

Hoare and Ole-Johan

Dahl. The March 1968 ACM letter's famous title, "Go To Statement Considered Harmful", was not the work of

Dijkstra, but of Niklaus

Wirth, then editor of Communications

of

the ACM. Dijkstra also strongly opposed the teaching of BASIC, a language whose programs

are typically GOTO-laden. Dijkstra

was known to be a fan of ALGOL

60, and worked on the team that implemented the first compiler for that language. Dijkstra and Jaap

Zonneveld, who collaborated on the compiler, agreed not to shave

until the project was completed. Dijkstra

wrote two important papers in 1968, devoted to the structure of a

multiprogramming operating system called THE,

and

to Co-operating

Sequential

Processes. From the

1970s, Dijkstra's chief interest was formal

verification. The prevailing opinion at the time was that one

should first write a program and then provide a mathematical

proof of correctness.

Dijkstra

objected noting that the resulting proofs are long and

cumbersome, and that the proof gives no insight on how the program was

developed. An alternative method is program

derivation, to "develop proof and program hand in hand". One

starts with a mathematical specification of what a program is

supposed to do and applies mathematical transformations to the

specification until it is turned into a program that can be executed. The resulting program is then known to be correct by construction.

Much

of Dijkstra's later work concerns ways to streamline mathematical

argument. In a 2001 interview, he stated a desire for

"elegance", whereby the correct approach would be to process thoughts

mentally, rather than attempt to render them until they are complete.

The analogy he made was to contrast the compositional approaches of Mozart and Beethoven. Dijkstra

was one of the early pioneers in the field of distributed computing. In

particular, his paper "Self-stabilizing Systems in Spite of Distributed

Control" started the sub-field of self-stabilization. Many

of

his opinions on computer science and programming have become

widespread. For example, he is famed for coining the popular

programming phrase "two or more, use a for," alluding to the rule of

thumb that when you find yourself processing more than one instance of

a data structure, it is time to consider encapsulating that logic

inside a loop. He was the first to make the claim that programming is

so inherently complex that, in order to manage it successfully,

programmers need to harness every trick and abstraction possible. When

expressing the abstract nature of computer science, he once said,

"computer science is no more about computers than astronomy is about

telescopes." He died in Nuenen, Netherlands on August 6, 2002 after a

long struggle with cancer.

The

following year, the ACM (Association

for Computing Machinery) PODC Influential Paper Award in

distributed computing was renamed the Dijkstra

Prize in his honour. Dijkstra

was known for his habit of carefully composing manuscripts with his

fountain pen. The manuscripts are called EWDs, since Dijkstra numbered

them with EWD,

his initials, as a prefix. According to Dijkstra himself, the EWDs

started when he moved from the Mathematical Centre in Amsterdam to the

Technological University (then TH) Eindhoven. After going to the TUE

Dijkstra experienced a writer's block for more than a year. Looking

closely at himself he realized that if he wrote about things they would

appreciate at the MC in Amsterdam his colleagues in Eindhoven would not

understand; if he wrote about things they would like in Eindhoven, his

former colleagues in Amsterdam would look down on him. He then decided

to write only for himself, and in this way the EWD's were born.

Dijkstra would distribute photocopies of a new EWD among his

colleagues; as many recipients photocopied and forwarded their copy,

the EWDs spread throughout the international computer science

community. The topics were computer science and mathematics, and

included trip reports, letters, and speeches. More than 1300 EWDs have

since been scanned, with a growing number transcribed to facilitate

search, and are available online at the Dijkstra archive of the

University of Texas. One of

Dijkstra's sidelines was serving as Chairman

of

the Board of the

fictional Mathematics Inc., a company that he imagined having commercialized the production of

mathematical theorems in the same way that

software companies had commercialized the production of computer

programs. He invented a number of activities and challenges of

Mathematics Inc. and documented them in several papers in the EWD

series. The imaginary company had produced a proof of the Riemann

Hypothesis but then

had great difficulties collecting royalties from mathematicians who had

proved results assuming the Riemann Hypothesis. The proof itself was a trade

secret (EWD 475).

Many of the company's proofs were rushed out the door and then much of

the company's effort had to be spent on maintenance (EWD 539). A more

successful effort was the Standard Proof for Pythagoras'

Theorem,

that replaced the more than 100 incompatible existing

proofs (EWD427). Dijkstra described Mathematics Inc. as "the most

exciting and most miserable business ever conceived" (EWD475). He

claimed that by 1974 his fictional company was the world's leading

mathematical industry with more than 75 percent of the world market

(EWD443). Having

invented much of the technology of software, Dijkstra eschewed the use

of computers in his own work for many decades. Almost all EWDs

appearing after 1972 were hand-written. When lecturing, he would write

proofs in chalk on a blackboard rather than using overhead foils, let

alone Powerpoint slides. Even after he succumbed to his UT colleagues’

encouragement and acquired a Macintosh computer, he used it only

for e-mail and for browsing the World Wide Web.