<Back to Index>

- Physician Ronald Ross, 1857

- Painter Georges Braque, 1882

- Minister of the Kingdom of Portugal Sebastião José de Carvalho e Melo, 1st Count of Oeiras, 1st Marquis of Pombal, 1699

PAGE SPONSOR

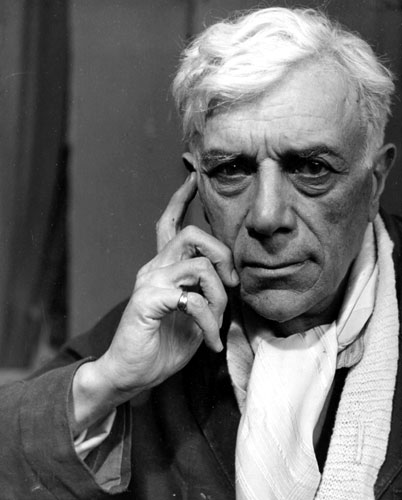

Georges Braque (13 May 1882 – 31 August 1963) was a major 20th century French painter and sculptor who, along with Pablo Picasso, developed the art movement known as Cubism.

Georges Braque was born in Argenteuil, Val-d'Oise. He grew up in Le Havre and trained to be a house painter and decorator like his father and grandfather. However, he also studied serious painting in the evenings at the École des Beaux-Arts, in Le Havre, from about 1897 to 1899. In Paris, he apprenticed with a decorator and was awarded his certificate in 1902. The following year, he attended the Académie Humbert, also in Paris, and painted there until 1904. It was here that he met Marie Laurencin and Francis Picabia.

His earliest works were impressionistic, but after seeing the work exhibited by the Fauves in 1905, Braque adopted a Fauvist style. The Fauves, a group that included Henri Matisse and André Derain among others, used brilliant colors and loose structures of forms to capture the most intense emotional response. Braque worked most closely with the artists Raoul Dufy and Othon Friesz, who shared Braque's hometown of Le Havre, to develop a somewhat more subdued Fauvist style. In 1906, Braque traveled with Friesz to L'Estaque, to Antwerp, and home to Le Havre to paint.

In May 1907, he successfully exhibited works in the Fauve style in the Salon des Indépendants. The same year, Braque's style began a slow evolution as he came under the strong influence of Paul Cézanne, who died in 1906, and whose works were exhibited in Paris for the first time in a large scale, museum-like retrospective in September 1907. The 1907 Cézanne retrospective at the Salon d'Automne greatly impacted the direction that the avant-garde in Paris took, leading to the advent of Cubism.

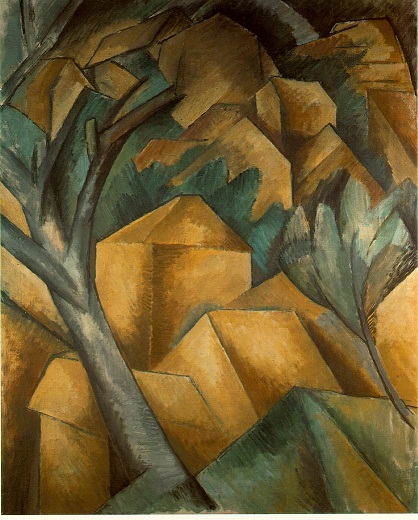

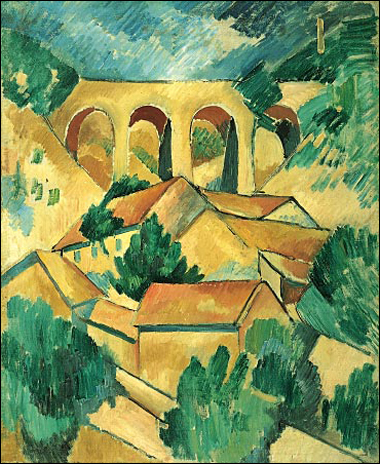

Braque's

paintings

of 1908 – 1913 began to reflect his new interest in geometry

and simultaneous perspective.

He

conducted an intense study of the effects of light and perspective

and the technical means that painters use to represent these effects,

appearing to question the most standard of artistic conventions. In his

village scenes, for example, Braque frequently reduced an architectural

structure to a geometric form approximating a cube, yet rendered its

shading so that it looked both flat and three-dimensional by

fragmenting the image. He showed this in the painting "House

at

L'estaque". In this way, Braque called attention to the very

nature of visual illusion and artistic representation. Beginning

in 1909, Braque began to work closely with Pablo

Picasso, who had been developing a similar approach to painting. At

the time Pablo Picasso was influenced by Gauguin,

Cézanne, African

tribal

masks and Iberian

sculpture, while Braque was mostly interested in developing

Cézanne's idea's of multiple perspectives. “A comparison of the

works of Picasso and Braque during 1908 reveals that the effect of his

encounter with Picasso was more to accelerate and intensify Braque’s

exploration of Cézanne’s ideas, rather than to divert his

thinking in any essential way.” The invention of Cubism was

a joint effort between Picasso and Braque, then residents of Montmartre,

Paris.

These artists were the movement's main innovators. After meeting

in October or November 1907, Braque and Picasso, in

particular, began working on the development of Cubism in 1908. Both

artists produced paintings of monochromatic color and complex patterns

of faceted form, now called Analytic

Cubism. A

decisive moment in its development occurred during the summer of 1911,

when

Georges Braque and Pablo

Picasso painted

side by side in Céret,

in

the French Pyrenees, each artist producing paintings that are

difficult — sometimes virtually impossible — to distinguish from those of

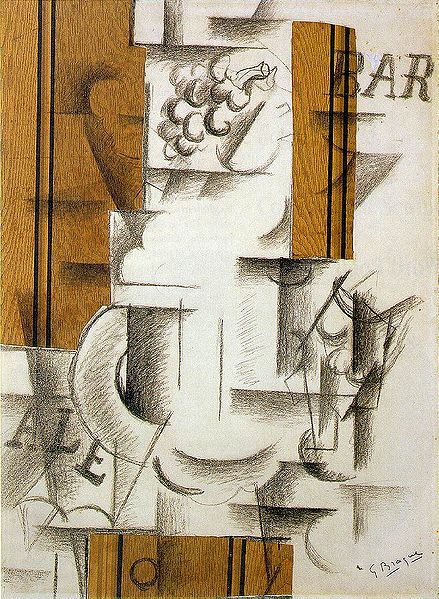

the other. In 1912, they began to experiment with collage and papier

collé. Their

productive collaboration continued and they worked closely together

until the outbreak of World

War

I in 1914 when

Braque enlisted in the French Army, leaving Paris to fight in the First

World

War. French

art critic Louis

Vauxcelles first

used the term Cubism,

or

"bizarre cubiques", in 1908 after seeing a picture by Braque. He

described it as 'full of little cubes', after which the term quickly

gained wide use although the two creators did not initially adopt it.

Art historian Ernst

Gombrich described

cubism as "the most radical attempt to stamp out ambiguity and to

enforce one reading of the picture - that of a man-made construction, a

colored canvas." The Cubist movement spread quickly

throughout Paris and Europe. Braque

was severely wounded in the war, and when he resumed his artistic

career in 1917 he moved away from the harsher abstraction of cubism.

Working alone, he developed a more personal style, characterized by

brilliant color and textured surfaces and — following his move to the Normandy seacoast — the reappearance

of the human figure. He painted many still

life subjects

during this time, maintaining his emphasis on structure. During his

recovery he became a close friend of the cubist artist Juan

Gris. However,

he nonetheless continued to work throughout the remainder of his life,

producing a considerable number of distinguished paintings, graphics,

and sculptures, all imbued with a pervasive contemplative quality.

Braque, along with Matisse, is credited for introducing Pablo Picasso to Fernand

Mourlot, and most of the lithographs and book illustrations he

himself created in the 1940s and '50s were produced at the Mourlot

Studios. He died on 31 August 1963, in Paris. He is buried in the

church cemetery in Saint-Marguerite-sur-Mer, Normandy, France. Braque's

work is in most major museums throughout the world. Braque

believed that an artist experienced beauty "… in terms of volume, of

line, of mass, of weight, and through that beauty [he] interpret[s] [his] subjective impression...” He described "objects

shattered into fragments… [as] a way of getting closest to the

object… Fragmentation helped me to establish space and movement in

space”. He adopted a monochromatic and neutral color palette

in the belief that such a palette would work simultaneously with the

form, instead of interfering with the viewer's conception of space; and

would focus, rather than distract, the viewer from the subject matter

of the painting. Although

Braque began his career painting landscapes, in 1908, he, alongside

Picasso, discovered the advantages of painting still

lifes instead.

Braque explained that he, “… began to concentrate on still-lifes,

because in the still-life you have a tactile, I might almost say a

manual space… This answered to the hankering I have always had to touch

things and not merely see them… In tactile space you measure the

distance separating you from the object, whereas in visual space you

measure the distance separating things from each other. This is what

led to, long ago, from landscape to still-life” A still-life was also more

accessible, in relation to perspective,

than

landscape, and permitted the artist to see the multiple

perspectives of the object. Braque's early interest in the still life

reappeared in the 1930s. During

the period between the wars, Braque exhibited a looser and freer

approach to Cubism, intensifying his color use and a looser rendering

of objects. However, he still remained strongly committed to the cubist

method of simultaneous perspective and fragmentation. In contrast to

Picasso, who continuously reinvented his approach to painting,

producing both representational and cubist images, and incorporating surrealist ideas into his work, Braque

continued in the Cubist style, producing luminous, other-worldly still

life and figure compositions. By the time of his death in 1963, he was

regarded as one of the elder statesmen of the School

of

Paris, and of modern

art.