<Back to Index>

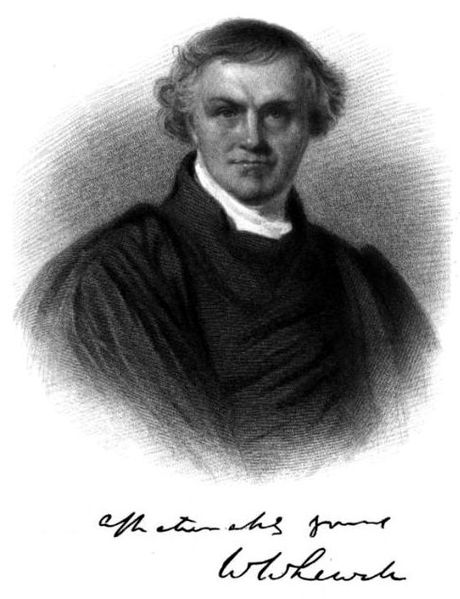

- Philosopher and Historian William Whewell, 1794

- Painter Alexei Kondratyevich Savrasov, 1830

- French Revolutionary Jean-Paul Marat, 1743

PAGE SPONSOR

William Whewell (24 May 1794 – 6 March 1866) was an English polymath, scientist, Anglican priest, philosopher, theologian, and historian of science.

Whewell was born in Lancaster. His father, a carpenter, wished him to follow his trade, but his success in mathematics at Lancaster and Heversham grammar schools won him an exhibition (a type of scholarship) at Trinity College, Cambridge (1812). In 1814 he was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal for poetry. He was Second Wrangler in 1816, President of the Cambridge Union Society in 1817, became fellow and tutor of his college, and, in 1841, succeeded Dr Christopher Wordsworth as master. He was professor of mineralogy from 1828 to 1832 and Knightbridge Professor of Philosophy (then called "moral theology and casuistical divinity") from 1838 to 1855.

Whewell died in Cambridge 1866 as a result of a fall from his horse.

What is most often remarked about Whewell is the breadth of his endeavours. At a time when men of science were becoming increasingly specialised, Whewell appears as a vestige of an earlier era when men of science dabbled in a bit of everything. He researched ocean tides (for which he won the Royal Medal), published work in the disciplines of mechanics, physics, geology, astronomy, and economics, while also finding the time to compose poetry, author a Bridgewater Treatise, translate the works of Goethe, and write sermons and theological tracts.

For

all these pursuits, it comes as no surprise that his best-known works

are two voluminous books which attempt to map and systematize the

development of the sciences, History of the Inductive Sciences (1837) and The Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, Founded Upon Their History (1840). While the History traced how each branch of the sciences had evolved since antiquity, Whewell viewed the Philosophy as

the “Moral” of the previous work as it sought to extract a universal

theory of knowledge through the history he had just traced. In the Philosophy, Whewell attempted to follow Francis Bacon's

plan for discovery of an effectual art of discovery. He examined ideas

("explication of conceptions") and by the "colligation of facts"

endeavoured to unite these ideas with the facts and so construct

science. But no art of discovery, such as Bacon anticipated, follows,

for "invention, sagacity, genius" are needed at each step. Whewell analysed inductive reasoning into three steps: Upon

these follow special methods of induction applicable to quantity: the

method of curves, the method of means, the method of least squares and

the method of residues, and special methods depending on resemblance

(to which the transition is made through the law of continuity), such

as the method of gradation and the method of natural classification. In Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences Whewell was the first to use the term "consilience" to discuss the unification of knowledge between the different branches of learning.

Here, as in his ethical doctrine, Whewell was moved by opposition to contemporary English empiricism. Following Immanuel Kant, he asserted against John Stuart Mill the a priori nature of necessary truth, and by his rules for the construction of conceptions he dispensed with the inductive methods of Mill.

One

of Whewell's greatest gifts to science was his wordsmithing. He often

corresponded with many in his field and helped them come up with new terms for their discoveries. In fact, Whewell came up with the term scientist itself. (They had previously been known as "natural philosophers" or "men of science"). Whewell also contributed the terms physicist, consilience, catastrophism, and uniformitarianism, amongst others; Whewell suggested the terms anode and cathode to Michael Faraday.

Whewell introduced what is now called the Whewell equation, an equation defining the shape of a curve without reference to an arbitrarily chosen coordinate system.

Whewell was prominent not only in scientific research and philosophy, but also in university and college administration. His first work, An Elementary Treatise on Mechanics (1819), cooperated with those of George Peacock and John Herschel in

reforming the Cambridge method of mathematical teaching. His work and

publications also helped influence the recognition of the moral and

natural sciences as an integral part of the Cambridge curriculum. In

general, however, especially in later years, he opposed reform: he defended the tutorial system, and in a controversy with Connop Thirlwall (1834), opposed the admission of Dissenters;

he upheld the clerical fellowship system, the privileged class of

"fellow-commoners," and the authority of heads of colleges in

university affairs. He opposed the appointment of the University

Commission (1850), and wrote two pamphlets (Remarks) against the

reform of the university (1855). He stood against the scheme of

entrusting elections to the members of the senate and instead,

advocated the use of college funds and the subvention of scientific and

professorial work.

Aside from Science, Whewell was also interested in the history of architecture throughout his life. He is best known for his writings on Gothic architecture, specifically his book, Architectural Notes on German Churches (first

published in 1830). In this work, Whewell established a strict

nomenclature for German Gothic churches and came up with a theory of

stylistic development. His work is associated with the "scientific

trend" of architectural writers, along with Thomas Rickman and Robert Willis. Between 1835 and 1861 Whewell produced various works on the philosophy of morals and politics, the chief of which, Elements of Morality, including Polity, was published in 1845. The peculiarity of this work — written from what is known as the intuitional point of view

-- is

its fivefold division of the springs of action and of their objects, of

the primary and universal rights of man (personal security, property,

contract, family rights and government), and of the cardinal virtues (benevolence, justice, truth, purity and order). Among Whewell's other works — too numerous to mention — were popular writings such as the third Bridgewater Treatise Astronomy and General Physics considered with reference to Natural Theology (1833), and the essay, Of the Plurality of Worlds (1854), in which he argued against the probability of life on other planets, and also the Platonic Dialogues for English Readers (1850 – 1861), the Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy in England (1852), the essay, Of a Liberal Education in General, with particular reference to the Leading Studies of the University of Cambridge (1845), the important edition and abridged translation of Hugo Grotius, De jure belli ac pacis (1853), and the edition of the Mathematical Works of Isaac Barrow (1860). Whewell was one of the Cambridge dons whom Charles Darwin met during his education there, and after the Beagle voyage when Darwin was at the very start of The Origin of Species Darwin placed a citation from Whewell's Bridgewater Treatise showing his ideas to be founded on a natural theology of a creator establishing laws: "But

with regard to the material world, we can at least go so far as this - we

can perceive that events are brought about not by insulated

interpositions of Divine power, exerted in each particular case, but by

the establishment of general laws."