<Back to Index>

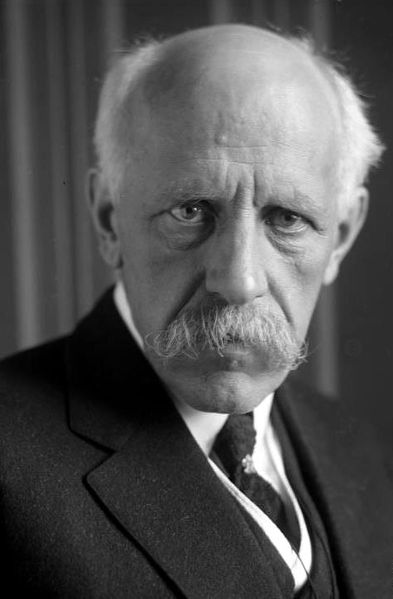

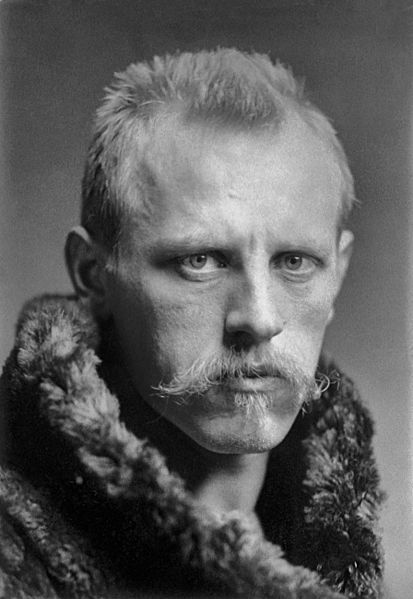

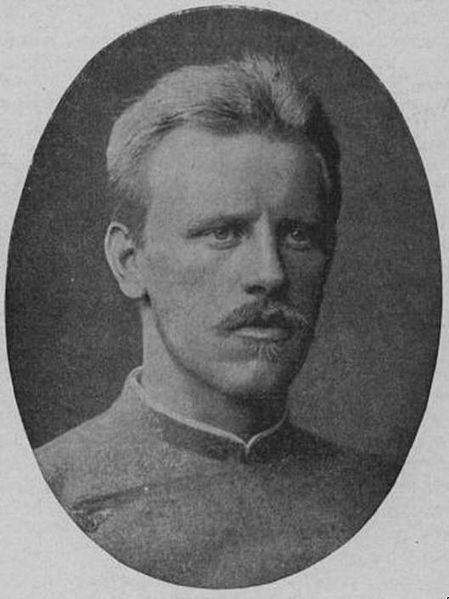

- Explorer Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen, 1861

- Author Aleksis Kivi, 1834

- Founder of Fatah Khalil Ibrahim al-Wazir "Abu Jihad", 1935

PAGE SPONSOR

Fridtjof Wedel-Jarlsberg Nansen (10 October 1861 – 13 May 1930) was a Norwegian explorer, scientist, diplomat, humanitarian and Nobel laureate. In his youth a champion skier and ice skater, he led the first crossing of the Greenland interior in 1888, and won international fame after reaching a record northern latitude of 86°13' during his North Pole expedition of 1893 – 96. Although he retired from exploration after his return to Norway, his techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a generation of subsequent Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.

Nansen studied zoology at the University of Christiania, and later worked as a curator at the Bergen Museum where

his work on the central nervous system of lower marine creatures earned

him a doctorate and helped establish modern theories of neurology. After 1896 his main scientific interest switched to oceanography;

in the course of his researches he made many scientific cruises, mainly

in the North Atlantic, and contributed to the development of modern

oceanographic equipment. As one of his country's leading citizens, in

1905 Nansen spoke out for the ending of Norway's union with Sweden, and

was instrumental in persuading Prince Charles of Denmark to

accept the throne of the newly independent Norway. Between 1906 and

1908 he served as the Norwegian representative in London, where he

helped negotiate the Integrity Treaty that guaranteed Norway's

independent status. In the final decade of his life Nansen devoted himself primarily to the League of Nations, following his appointment in 1921 as the League's High Commissioner for Refugees. In 1922 he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on behalf of the displaced victims of the First World War and related conflicts. Among the initiatives he introduced was the "Nansen passport"

for stateless persons, a certificate recognised by more than 50

countries. He worked on behalf of refugees until his sudden death in

1930, after which the League established the Nansen International Office for Refugees to

ensure that his work continued. This office received the Nobel Peace

Prize for 1938. Nansen was honoured by many nations, and his name is

commemorated in numerous geographical features, particularly in the

polar regions. The Nansen family originated in Denmark. Hans Nansen (1598 – 1667), a trader, was an early explorer of the White Sea region of the Arctic Ocean. In later life he settled in Copenhagen, becoming the city's borgmester in

1654. Later generations of the family lived in Copenhagen until the

mid 18th century, when Ancher Antoni Nansen moved to Norway (then a

Danish province). His son, Hans Leierdahl Nansen (1764 – 1821), was a

magistrate first in the Trondheim district, later in Jæren. After Norway's separation from Denmark in 1814, he entered national political life as the representative for Stavanger in the first Storting,

the Norwegian parliament, and became a strong advocate of union with

Sweden. After suffering a paralytic stroke in 1821 Hans Leierdahl

Nansen died, leaving a four-year-old son, Baldur Fridtjof Nansen, the

explorer's father. Baldur was a lawyer without ambitions for public life, who became Reporter to the Supreme Court of Norway. He married twice, the second time to Adelaide Johanna Isidora Wedel-Jarlsberg, a niece of Herman Wedel-Jarlsberg who had helped frame the Norwegian constitution of 1814 and was later the Swedish king's Norwegian Viceroy. Baldur and Adelaide settled at Store Frøen, an estate a few miles north of Norway's capital city, Christiania (since

renamed Oslo). The couple had three children; the first died in infancy, the second, born 10 October 1861, was Fridtjof Nansen. Store

Frøen's rural surroundings shaped the nature of Nansen's

childhood. In the short summers the main activities were swimming and

fishing, while in the autumn the chief pastime was hunting for game in

the forests. The long winter months were devoted mainly to skiing,

which Nansen began to practice at the age of two, on improvised skis. At the age of 10 he defied his parents and attempted the ski jump at the nearby Huseby installation.

This exploit had near disastrous consequences, as on landing the skis

dug deep into the snow, pitching the boy forward: "I, head first,

described a fine arc in the air ... [W]hen I came down again I bored

into the snow up to my waist. The boys thought I had broken my neck,

but as soon as they saw there was life in me ... a shout of mocking

laughter went up." Nansen's

enthusiasm for skiing was undiminished, though as he records, his

efforts were overshadowed by those of the skiers from the mountainous

region of Telemark, where a new style of skiing was being developed. "I saw this was the only way", wrote Nansen later. At school, Nansen worked adequately without showing any particular aptitude. Studies took second place to sports, or to expeditions into the forests where he would live "like Robinson Crusoe" for weeks at a time. Through

such experiences Nansen developed a marked degree of self-reliance. He

became an accomplished skier and a highly proficient skater.

Life was disrupted when, in the summer of 1877, Adelaide Nansen died

suddenly. Distressed, Baldur Nansen sold the Store Frøen

property and moved with his two sons to Christiania. Nansen's

sporting prowess continued to develop; at 18 he broke the world

one-mile (1.6 km) skating record, and in the following year won the

national cross-country skiing championship, a feat he would repeat on

11 subsequent occasions. In 1880 Nansen passed his university entrance examination, the examen artium. He decided to study zoology,

claiming later that he chose the subject because he thought it offered

the chance of a life in the open air. He began his studies at the

University of Christiania early in 1881. Early in 1882 Nansen took "...the first fatal step that led me astray from the quiet life of science." Professor Robert Collett of

the university's zoology department proposed that Nansen take a sea

voyage, to study Arctic zoology at first hand. Nansen was enthusiastic,

and made arrangements through a recent acquaintance, Captain Axel

Krefting, commander of the sealer Viking. The

voyage began on 11 March 1882 and extended over the following five

months. In the weeks before sealing started, Nansen was able to

concentrate on scientific studies. From

water samples he showed that, contrary to previous assumption, sea ice

forms on the surface of the water rather than below. His readings also

demonstrated that the Gulf Stream flows beneath a cold layer of surface water. Through the spring and early summer Viking roamed between Greenland and Spitsbergen in

search of seal herds. Nansen became an expert marksman, and on one day

proudly recorded that his team had shot 200 seal. In July, Viking became

trapped in the ice close to an unexplored section of the Greenland

coast; Nansen longed to go ashore, but this was impossible. However, he began to develop the idea that the Greenland icecap might be explored, or even crossed. On 17 July the ship broke free from the ice, and early in August was back in Norwegian waters. Nansen

did not resume formal studies at the university. Instead, on Collett's

recommendation, he accepted a post as curator in the zoological department of the Bergen Museum. He was to spend the next six years of his life there — apart from a six-month sabbatical tour of Europe — working and studying with leading figures such as Gerhard Armauer Hansen, the discoverer of the leprosy bacillus, and Daniel Cornelius Danielssen, the museum's director who had turned it from a backwater collection into a centre of scientific research and education. Nansen's chosen area of study was the then relatively unexplored field of neuroanatomy, specifically the central nervous system of lower marine creatures.

Before leaving for his sabbatical in February 1886 he published a paper

summarising his research to date, in which he stated that "anastomoses

or unions between the different ganglion cells" could not be

demonstrated with certainty. This unorthodox view, confirmed by the

simultaneous researches of the embryologist Wilhelm His and the psychiatrist August Forel, made Nansen a co-founder of the modern theory of the nervous system. His subsequent paper, The Structure and Combination of Histological Elements of the Central Nervous System, published in 1887, became his doctoral thesis. The

idea of an expedition across the Greenland icecap grew in Nansen's mind

throughout his Bergen years. In 1887, after the submission of his doctoral thesis,

he finally began organising this project. Before then, the two most

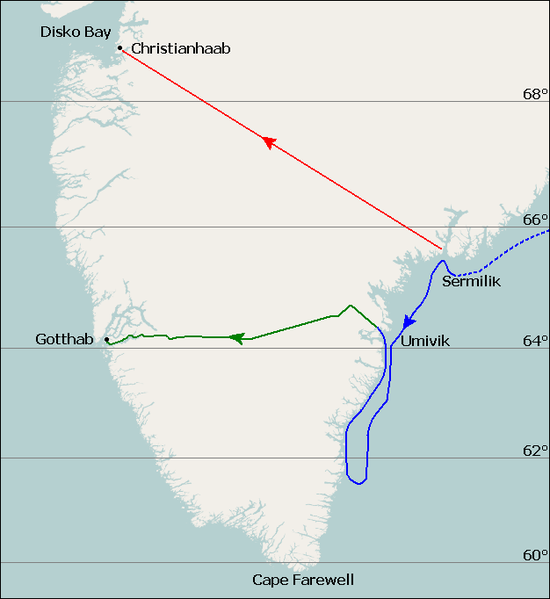

significant penetrations of the Greenland interior had been those of Adolf Erik Nordenskiöld in 1883, and Robert Peary in 1886. Both had set out from Disko Bay on the western coast, and had travelled about 160 kilometres (100 mi) eastward before turning back. By

contrast, Nansen proposed to travel from east to west, ending rather

than beginning his trek at Disko Bay. A party setting out from the

inhabited west coast would, he reasoned, have to make a return trip, as

no ship could be certain of reaching the dangerous east coast and

picking them up. By

starting from the east — assuming that a landing could be made

there — Nansen's would be a one-way journey towards a populated area. The

party would have no line of retreat to a safe base; the only way to go

would be forward, a situation that fitted Nansen's philosophy

completely. Nansen

rejected the complex organisation and heavy manpower of other Arctic

ventures, and instead planned his expedition for a small party of six.

Supplies would be manhauled on

specially designed lightweight sledges. Much of the equipment,

including sleeping bags, clothing and cooking stoves, also needed to be

designed from scratch. These plans received a generally poor reception in the press; one

critic had no doubt that "if [the] scheme be attempted in its present

form ... the chances are ten to one that he will ... uselessly throw

his own and perhaps others' lives away". The

Norwegian parliament refused to provide financial support, believing

that such a potentially risky undertaking should not be encouraged. The

project was eventually launched with a donation from a Danish

businessman, Augustin Gamél; the rest came mainly from small

contributions from Nansen's countrymen, through a fundraising effort

organised by students at the university. Despite

the adverse publicity, Nansen received numerous applications from

would-be adventurers. He wanted expert skiers, and attempted to recruit

from the skiers of Telemark, but his approaches were rebuffed. Nordenskiöld had advised Nansen that Sami people, from Finnmark in the far north of Norway, were expert snow travellers, so Nansen recruited a pair. The remaining places went to Otto Sverdrup, a former sea captain who had more recently worked as a forester; Oluf Christian Dietrichson, an army officer, and Kristian Kristiansen, an acquaintance of Sverdrup's. All had experience of outdoor life in extreme conditions, and were experienced skiers. Just

before the party's departure, Nansen attended a formal examination at

the university, which had agreed to receive his doctoral thesis. In

accordance with custom he was required to defend his work before

appointed examiners acting as "devil's advocates". He left before knowing the outcome of this process. On 3 June 1888 Nansen's party was picked up from the north-western Icelandic port of Ísafjörður by the sealer Jason. A week later the Greenland coast was sighted, but progress was hindered by thick pack ice.

On 17 July, with the coast still 20 kilometres (12 mi) away,

Nansen decided to launch the small boats; they were within sight of the Sermilik Fjord, which Nansen believed would offer a route up on to the icecap. The expedition left Jason "in good spirits and with the highest hopes of a fortunate result", according to Jason's captain. There

followed days of extreme frustration for the party as, prevented by

weather and sea conditions from reaching the shore, they drifted

southwards with the ice. Most of this time was spent camping on the ice

itself — it was too dangerous to launch the boats. By 29 July they were

380 kilometres (240 mi) south of the point where they had left the

ship. On that day they finally reached land, but were too far south to

begin the crossing. After a brief rest, Nansen ordered the team back

into the boats and to begin rowing north. During

the next 12 days the party battled northward against the coastal

current. On the first day they encountered a large Eskimo encampment near Cape Bille, and

there were further occasional contacts with the nomadic native

population as the journey continued. On 11 August, when they had

covered about 200 kilometres (120 mi) and had reached Umivik Fjord,

Nansen decided that although they were still far south of his intended

starting place, they needed to begin the crossing before the season

became too advanced for travel. After

landing at Umivik, they spent the next four days preparing for their

journey, and on the evening of 15 August they set out. They were

heading north-west, towards Christianhaab (now Qasigiannguit) on the west Greenland shores of Disko Bay, 600 kilometres (370 mi) away. Over the next few days the party struggled to ascend the inland ice over a treacherous surface with many hidden crevasses. The weather was generally bad; on one occasion all progress was halted for three days by violent storms and continuous rain. On

26 August Nansen concluded that there was now no chance of reaching

Christianhaab by mid September, when the last ship was due to leave. He

therefore ordered a change of course, almost due west towards Godthaab (now

Nuuk), a shorter journey by at least 150 kilometres (93 mi). The

rest of the party, according to Nansen, "hailed the change of plan with

acclamation". They

continued climbing, until on 11 September they had reached a height of

8,922 feet (2,719 m) above sea level, the summit of the icecap.

From then on the downward slope made travelling easier, although the

terrain was difficult and the weather remained hostile. By 26 September they had battled their way down to the edge of a fjord that

ran westward towards Godthaab. From the available materials Sverdrup

constructed a makeshift boat, and on 29 September the party began the

last stage of the journey, sailing on the fjord. Five

days later, on 3 October 1888, they reached Godthaab, where they were

greeted by the town's Danish representative. His first words were to

inform Nansen that he had been awarded his doctorate, a matter that

"could not have been more remote from my thoughts at that moment". The

crossing had been accomplished in 49 days; throughout the journey the

team had maintained careful meteorological, geographical and other

records relating to the previously unexplored interior. Nansen

soon learned that no ship was likely to call at Godthaab until the

following spring. He and his party therefore spent the next seven

months in Greenland, hunting, fishing and studying the life of the

local inhabitants. On 15 April 1889 the Danish ship Hvidbjørnen finally

entered the harbour, and Nansen and his comrades prepared to depart.

"It was not without sorrow that we left this place and these people,

among whom we had enjoyed ourselves so well", Nansen recorded. Hvidbjørnen reached

Copenhagen on 21 May 1889. News of the crossing had preceded its

arrival, and Nansen and his companions were feted as heroes. This

welcome, however, was dwarfed by the reception in Christiania a week

later, when crowds of between thirty and forty thousand — a third of the

city's population — thronged the streets as the party made its way to the

first of a series of receptions. The interest and enthusiasm generated

by the expedition's achievement led directly to the formation that year of the Norwegian Geographical Society. Nansen

accepted the position of curator of the University of Christiania's

zoology collection, a post which carried a salary but involved no

duties; the university was satisfied by the association with the

explorer's name. Nansen's

main task in the following weeks was writing his account of the

expedition, but he found time late in June to visit London, where he met the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII), and addressed a meeting of the Royal Geographical Society (RGS). The RGS president, Sir Mountstuart Elphinstone Grant Duff,

said that Nansen has claimed "the foremost place amongst northern

travellers", and later awarded him the Society's prestigious Founder's

Medal. This was one of many honours Nansen received from institutions

all over Europe. He

was invited by a group of Australians to lead an expedition to

Antarctica, but declined, believing that Norway's interests would be

better served by a North Pole conquest. On 11 August 1889 Nansen announced his engagement to Eva Sars, the daughter of Michael Sars, a zoology professor who had died when Eva was 11 years old. The couple had met some years previously, at the skiing resort of Frognerseteren, where Nansen recalled seeing "two feet sticking out of the snow". Eva

was three years older than Nansen, and despite the evidence of this

first meeting, was an accomplished skier. She was also a celebrated

classical singer who had been coached in Berlin by Désirée Artôt, one-time paramour of Tchaikovsky.

The engagement surprised many, since Nansen had previously expressed

himself forcefully against the institution of marriage; Otto Sverdrup

assumed he had read the message wrongly. The wedding took place on 6 September 1889, less than a month after the engagement. Nansen

first began to consider the possibility of reaching the North Pole by

using the natural drift of the polar ice when, in 1884, he read the

theories of Henrik Mohn, the distinguished Norwegian meteorologist. Artefacts found on the Greenland coast had been identified as coming from the lost US Arctic exploration vessel Jeannette,

which had been crushed and sunk in June 1881 on the opposite side of

the Arctic Ocean, off the Siberian coast. Mohn surmised that the

location of the artefacts indicated the existence of an ocean current,

flowing from east to west all the way across the polar sea, possibly

over the pole itself. A strong enough ship might therefore enter the

frozen Siberian sea, and drift to the Greenland coast via the pole. This

idea remained with Nansen during the following years. After his triumphant

return from Greenland he began to develop a detailed plan for a polar

venture, which he made public in February 1890 at a meeting of the

recently formed Norwegian Geographical Society. Previous expeditions,

he argued, had approached the North Pole from the west, and had failed

because they were working against the prevailing east-west current. The secret of success was to work with this

current. A workable plan, Nansen said, would require a small, strong

and manoeuvrable ship capable of carrying fuel and provisions for

twelve men for five years. The ship would sail to the approximate

location of Jeannette's sinking,

and would enter the ice. It would then drift west with the current

towards the pole and beyond it, eventually reaching the sea between

Greenland and Spitsbergen. Many experienced polar hands were dismissive of Nansen's plans. The retired American explorer Adolphus Greely called the idea "an illogical scheme of self-destruction". Sir Allen Young, a veteran of the searches for Sir John Franklin's lost expedition, and Sir Joseph Hooker, who had sailed south with James Clark Ross in 1839 – 43, were equally dismissive. However,

after an impassioned speech Nansen secured the support of the Norwegian

parliament, which voted him a grant. The balance of funding was met by

private donations and from a national appeal. Nansen chose Colin Archer,

Norway's leading shipbuilder and naval architect, to design and build a

suitable ship for the planned expedition. Using some of the hardest

timber available, and an intricate system of crossbeams and braces

throughout its length, Archer built a vessel of extraordinary strength.

Its rounded hull was designed so that there was nothing upon which ice

could get a grip. Speed and sailing performance were secondary to the

requirement of making the ship a safe and warm shelter during a

predicted lengthy confinement. With

an overall length of 128 feet (39 m) and a breadth of 36 feet

(11 m), the length - to - breadth ratio of just over three to one gave the

ship its stubby appearance, justified

by Archer thus: "A ship that is built with exclusive regard to its

suitability for [Nansen's] object must differ essentially from any

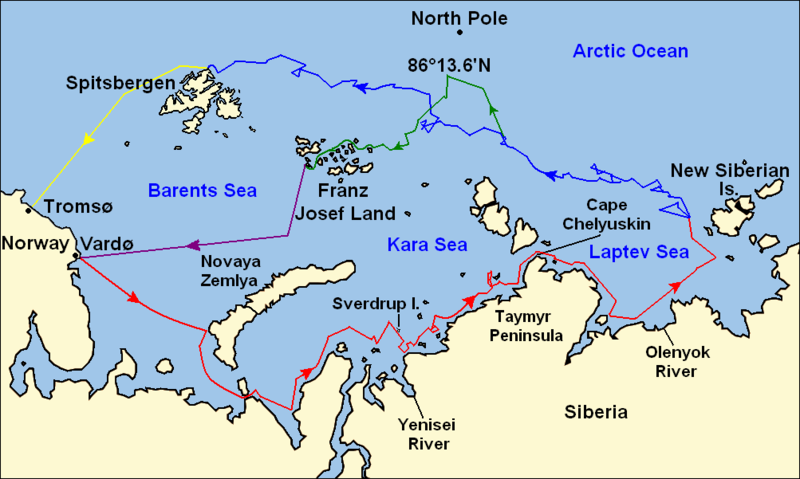

known vessel." The ship was launched by Eva Nansen at Archer's yard at Larvik, on 6 October 1892, and was named Fram, in English "Forward". From

thousands of applicants, Nansen chose a party of twelve. Otto Sverdrup

from the Greenland expedition was appointed captain of Fram and second - in - command of the expedition. Competition for places on the voyage was such that reserve Army lieutenant and dog driving expert Hjalmar Johansen signed on as ship's stoker, the only position available. Fram left Christiania on 24 June 1893, cheered on by thousands of well-wishers. After a slow journey 'round the coast, the final port of call was Vardø, in the far north-east of Norway. Fram left Vardø on 21 July, following the North-East Passage route

pioneered by Nordenskiöld in 1878 – 79, along the northern coast of

Siberia. Progress was impeded by fog and ice conditions in the mainly

uncharted seas. The crew also experienced the dead water phenomenon,

where a ship's forward progress is impeded by friction caused by a

layer of fresh water lying on top of heavier salt water. Nevertheless, Cape Chelyuskin, the most northerly point of the Eurasian continental mass, was passed on 10 September. Ten days later, as Fram approached the area in which Jeannette had been crushed, heavy pack ice was

sighted at around latitude 78°N. Nansen followed the line of the

pack northwards to a position recorded as 78°49'N, 132°53'E,

before ordering engines stopped and the rudder raised. From this point Fram's drift began. The first weeks in the ice were frustrating, as the drift moved unpredictably, sometimes north, sometimes south; by 19 November Fram's latitude was south of that at which she had entered the ice. Only

after the turn of the year, in January 1894, did the northerly

direction become generally settled; the 80° mark was finally passed

on 22 March. Nansen calculated that, at this rate, it might take the ship five years to reach the pole. As

the ship's northerly progress continued at a rate rarely above a mile

(1.6 km) a day, Nansen began privately to consider a new plan — a dog sledge journey towards the pole. With

this in mind he began to practice dog driving, making many experimental

journeys over the ice. In November Nansen announced his plan: when the

ship passed latitude 83° he and Hjalmar Johansen would leave the

ship with the dogs and make for the pole while Fram,

under Sverdrup, continued its drift until it emerged from the ice in

the North Atlantic. After reaching the pole, Nansen and Johansen would

make for the nearest known land, the recently discovered and sketchily

mapped Franz Josef Land. They would then cross to Spitsbergen where they would find a ship to take them home. The crew spent the rest of the 1894 – 95 winter preparing clothing and equipment for the forthcoming sledge journey. Kayaks were built, to be carried on the sledges until needed for the crossing of open water. Preparations

were interrupted early in January when violent tremors shook the ship.

The crew disembarked, fearing that the vessel would be crushed, but Fram proved herself equal to the danger. On 8 January 1895 the ship's position was 83°34'N, above Greely's previous Farthest North record of 83°24. On 14 March 1895, after two false starts and with the ship's position at 84°4'N, Nansen and Johansen began their journey. Nansen

had allowed 50 days to cover the 356 nautical miles (660 km;

410 mi) to the pole, an average daily journey of seven nautical miles

(13 km; 8.1 mi). After a week of travel a sextant observation

indicated that they were averaging nine nautical miles a day,

(17 km; 10 mi), putting them ahead of schedule. However,

uneven surfaces made skiing more difficult, and their speeds slowed.

They also realised that they were marching against a southerly drift,

and that distances travelled did not necessarily equate to northerly

progression. On

3 April Nansen began to wonder whether the pole was, indeed,

attainable. Unless their speed improved, their food would not last them

to the pole and then on to Franz Josef Land. He confided in his diary:

"I have become more and more convinced we ought to turn before time." On

7 April, after making camp and observing that the way ahead was "a

veritable chaos of iceblocks stretching as far as the horizon", Nansen

decided to turn south. He recorded the latitude of the final northerly

camp as 86°13.6'N, almost three degrees beyond the previous

Farthest North mark. It

was soon clear that this land was part of a group of islands. As they

moved slowly southwards, Nansen tentatively identified a headland as

Cape Felder, on the western edge of Franz Josef Land. Towards the end

of August, as the weather grew colder and travel became increasingly

difficult, Nansen decided to camp for the winter. In

a sheltered cove, with stones and moss for building materials, the pair

erected a hut which was to be their home for the next eight months. With ready supplies of bear, walrus and seal to keep their larder stocked, their principal enemy was not hunger but inactivity. After

muted Christmas and New Year celebrations, in slowly improving weather

they began to prepare to leave their refuge, but it was 19 May 1896

before they were able to resume their journey. On 17 June, during a stop for repairs after the kayaks had been attacked by a walrus,

Nansen thought he heard sounds of a dog barking, and of voices. He went

to investigate, and a few minutes later saw the figure of a man

approaching. It was the British explorer Frederick Jackson, who was leading an expedition to Franz Josef Land and was camped at nearby Cape Flora on Northbrook Island.

The two were equally astonished by their encounter; after some awkward

hesitation Jackson asked: "You are Nansen, aren't you?", and received

the reply "Yes, I am Nansen." Johansen

was soon picked up, and the pair were taken to Cape Flora where, during

the following weeks, they recuperated from their ordeal. Nansen later

wrote that he could "still scarcely grasp" the sudden change of fortune; had it not been for the walrus attack that caused the delay, the two parties might have been unaware of each other's existence. On 7 August Nansen and Johansen boarded Jackson's supply ship Windward,

and sailed for Vardø where they arrived on the 13th. They were

greeted by Hans Mohn, the originator of the polar drift theory, who was

in the town by chance. The world was quickly informed by telegram of Nansen's safe return, but as yet there was no news of Fram. Taking the weekly mail steamer south, Nansen and Johansen reached Hammerfest on 18 August, where they learned that Fram had

been sighted. She had emerged from the ice north and west of

Spitsbergen, as Nansen had predicted, and was now on her way to

Tromsø. She had not passed over the pole, nor exceeded Nansen's

northern mark. Without delay Nansen and Johansen sailed for Tromsø, where they were reunited with their comrades. The homeward voyage to Christiania was a series of triumphant receptions at every port. On 9 September Fram was escorted into Christiania's harbour and welcomed by the largest crowds the city had ever seen. The

crew were received by King Oscar, and Nansen, reunited with family,

remained at the palace for several days as a special guest. Tributes

arrived from all over the world; typical was that from the British

mountaineer Edward Whymper,

who wrote that Nansen had made "almost as great an advance as has been

accomplished by all other voyages in the nineteenth century put

together". Nansen's

first task on his return was to write his account of the voyage. This

he did remarkably quickly, producing 300,000 words of Norwegian text by

November 1896; the English translation, titled Farthest North, was ready in January 1897. The book was an instant success, and secured Nansen's long-term financial future. Nansen included without comment the one significant adverse criticism of his conduct, that of Greely, who had written in Harper's Weekly on Nansen's decision to leave Fram and

strike for the pole: "It passes comprehension how Nansen could have

thus deviated from the most sacred duty devolving on the commander of a

naval expedition." During

the 20 years following his return from the Arctic, Nansen devoted most

of his energies to scientific work. In 1897 he accepted a professorship

in zoology at the University of Christiania, which gave him a base from which he could tackle the major task of editing the reports of the scientific results of the Fram expedition.

This was a much more arduous task than writing the expedition

narrative. The results were eventually published in six volumes, and

according to a later polar scientist, Robert Rudmose-Brown, "were to Arctic oceanography what the Challenger expedition results had been to the oceanography of other oceans." In

1900 Nansen became director of the Christiania based International

Laboratory for North Sea Research, and helped found the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea. Through his connection with the latter body, in the summer of 1900 Nansen embarked on his first visit to Arctic waters since the Fram expedition, a cruise to Iceland and Jan Mayen Land on the oceanographic research vessel Michael Sars, named after Eva's father. Shortly after his return he learned that his Farthest North record had been passed, by members of the Duke of the Abruzzi's

Italian expedition. They had reached 86°34N on 24 April 1900, in an

attempt to reach the North Pole from Franz Josef Land. Nansen

received the news philosophically: "What is the value of having goals

for their own sake? They all vanish ... it is merely a question of time. Nansen

was now considered an oracle by all would-be explorers of the north and

south polar regions. Abruzzi had consulted him, as had the Belgian Adrien de Gerlache, each of whom took expeditions to the Antarctic. Although Nansen refused to meet his own countryman and fellow explorer Carsten Borchgrevink (whom he considered a fraud), he gave advice to Robert Falcon Scott on polar equipment and transport, prior to the 1901 – 04 Discovery Expedition.

Nansen's advice that dogs provided the best means of polar travel was

politely ignored by Scott; nevertheless the two remained on good terms.

At one point Nansen seriously considered leading a South Pole

expedition himself, and asked Colin Archer to design two ships.

However, these plans remained on the drawing board. By 1901 Nansen's family had expanded considerably. A daughter, Liv, had been born just before Fram set out; a son, Kåre was born in 1897 followed by a daughter, Irmelin, in 1900 and a second son Odd in 1901. The family home, which Nansen had built in 1891 from the profits of his Greenland expedition book, was now too small. Nansen acquired a plot of land in the Lysaker district

and built, substantially to his own design, a large and imposing house

which combined some of the characteristics of an English manor house with features from the Italian renaissance. The house was ready for occupation by April 1902; Nansen called it Polhøgda (in

English "polar heights"), and it remained his home for the rest of his

life. A fifth and final child, son Asmund, was born at Polhøgda

in 1903. The union between Norway and Sweden,

imposed by the Great Powers in 1814, had been under considerable strain

through the 1890s, the chief issue in question being Norway's rights to

its own consular service. Nansen,

although not by inclination a politician, had spoken out on the issue

on several occasions in defence of Norway's interests. It

seemed, early in the 20th century that agreement between the two

countries might be possible, but hopes were dashed when negotiations

broke down in February 1905. The Norwegian government fell, and was

replaced by one led by Christian Michelsen, whose programme was one of separation from Sweden. In

February and March Nansen published a series of newspaper articles

which placed him firmly in the separatist camp. The new prime minister

wanted Nansen in the cabinet, but Nansen had no political ambitions. However, at Michelsen's request he went to London where, in a letter to The Times,

he presented Norway's legal case for a separate consular service to the

English speaking world. On 17 May 1905, Norway's Constitution Day,

Nansen addressed a large crowd in Christiania, saying: "Now have all

ways of retreat been closed. Now remains only one path, the way

forward, perhaps through difficulties and hardships, but forward for

our country, to a free Norway". He also wrote a book, Norway and the Union with Sweden, specifically to promote Norway's case abroad.

On

23 May the Storting passed the Consulate Act establishing a separate

consular service. King Oscar, refused his assent; on 27 May the

Norwegian cabinet resigned, but the king would not recognise this step.

On 7 June the Storting unilaterally announced that the union with

Sweden was dissolved. In a tense situation the Swedish government

agreed to Norway's request that the dissolution should be put to a

referendum of the Norwegian people. This

was held on 13 August 1905 and resulted in an overwhelming vote for

separation, at which point King Oscar relinquished the crown of Norway

while retaining the Swedish throne. A second referendum, held in

November, determined that the new independent state should be a monarchy rather

than a republic. In anticipation of this, Michelsen's government had

been considering the suitability of various princes as candidates for

the Norwegian throne. Faced with King Oscar's refusal to allow anyone

from his own House of Bernadotte to accept the crown, the favoured choice was Prince Charles of Denmark. In July 1905 Michelsen sent Nansen to Copenhagen on a secret mission to persuade Charles to accept the Norwegian throne. Nansen

was successful; shortly after the second referendum Charles was

proclaimed king, taking the name Haakon VII. He and his wife, the

British princess Maud, were crowned in the Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim on 22 June 1906. In April 1906 Nansen was appointed Norway's Ambassador in London. His

main task was to work with representatives of the major European powers

on an Integrity Treaty which would guarantee Norway's position. Nansen

was popular in England, and got on well with King Edward, though he

found court functions and diplomatic duties disagreeable; "frivolous

and boring" was his description. However, he was able to pursue his geographical and scientific interests through

contacts with the Royal Geographical Society and other learned bodies.

The Treaty was signed on 2 November 1907, and Nansen considered his

task complete. Resisting the pleas of, among others, King Edward that

he should remain in London, on 15 November Nansen resigned his post. A few weeks later, still in England as the king's guest at Sandringham, Nansen received word that Eva was seriously ill with pneumonia. On 8 December he set out for home, but before he reached Polhøgda he learned, from a telegram, that Eva had died. After

a period of mourning, Nansen returned to London. He had been persuaded

by his government to rescind his resignation until after King Edward's

state visit to Norway in April 1908. His formal retirement from the

diplomatic service was dated 1 May 1908, the same day on which his

university professorship was changed from zoology to oceanography. This

new designation reflected the general character of Nansen's more recent

scientific interests. In 1905 he had supplied the Swedish physicist Walfrid Ekman with the data which established the principle in oceanography known as the Ekman spiral. Based on Nansen's observations of ocean currents recorded during the Fram expedition,

Ekman concluded that the effect of wind on the sea's surface produced

currents which "formed something like a spiral staircase, down towards

the depths". In 1909 Nansen combined with Bjørn Helland-Hansen to publish an academic paper, The Norwegian Sea: its Physical Oceanography, based on the Michael Sars voyage of 1900. Nansen had by now retired from polar exploration, the decisive step being his release of Fram to his fellow Norwegian Roald Amundsen, who was planning a North Pole expedition. When Amundsen made his controversial change of plan and set out for the South Pole, Nansen stood by him. Between 1910 and 1914, Nansen participated in several oceanographic voyages. In 1910, aboard the Norwegian naval vessel Fridtjof, he carried out researches in the northern Atlantic, and in 1912 he took his own yacht, Veslemøy, to Bear Island and Spitsbergen. The main objective of the Veslemøy cruise was the investigation of salinity in the North Polar Basin. One of Nansen's lasting contributions to oceanography was his work designing instruments and equipment; the "Nansen bottle" for taking deep water samples remained in use into the 21st century, in a version updated by Shale Niskin. At

the request of the Royal Geographical Society, Nansen began work on a

study of Arctic discoveries, which developed into a two volume history

of the exploration of the northern regions up to the beginning of the

16th century. This was published in 1911 as Nord i Tåkeheimen ("In Northern Mists"). That year he renewed an acquaintance with Kathleen Scott, wife of Robert Falcon Scott whose Terra Nova Expedition had sailed for Antarctica in 1910. Biographer Roland Huntford has asserted that Nansen and Kathleen Scott enjoyed a brief love affair. Many women were attracted to Nansen, and he had a reputation as a womaniser. His

personal life was troubled around this time; in January 1913 he

received news of the suicide of Hjalmar Johansen, who had returned in disgrace from Amundsen's successful South Pole expedition. In March 1913, Nansen's youngest son Asmund died after a long illness. In

the summer of 1913 Nansen travelled to the Kara Sea, as part of a

delegation investigating a possible trade route between Western Europe

and the Siberian interior. The party then took a steamer down the Yenisei River to Krasnoyarsk, and travelled on the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok before

turning for home. The life and culture of the Russian peoples aroused

in Nansen an interest and sympathy he would carry through to his later

life. Immediately before the First World War, Nansen joined Helland-Hansen in an oceanographical cruise in eastern Atlantic waters.

On

the outbreak of war in 1914 Norway declared its neutrality, alongside

Sweden and Denmark. Nansen was appointed president of the Norwegian Union of Defence, but had few official duties, and continued with his professional work as far as circumstances permitted. As

the war progressed, the loss of Norway's overseas trade led to acute

shortages of food in the country, which became critical in April 1917

when the United States entered the war and placed extra restrictions on

international trade. Nansen was dispatched to Washington by the

Norwegian government; after months of discussion he secured food and

other supplies in return for the introduction of a rationing system.

When his government hesitated over the deal, he signed the agreement on

his own initiative. Within a few months of the war's end in November 1918 a draft agreement had been accepted by the Paris Peace Conference to create a League of Nations, as a means of resolving disputes between nations by peaceful means. The

foundation of the League at this time was providential as far as Nansen

was concerned, giving him a new outlet for his restless energy. He

became president of the Norwegian League of Nations Society, and

although the Scandinavian nations with their traditions of neutrality

initially held themselves aloof, his advocacy helped to ensure that

Norway became a full member of the League in 1920, and he became one of

its three delegates to the League's General Assembly. In

April 1920, at the League's request, Nansen began organising the

repatriation of around half a million prisoners of war, stranded in

various parts of the world. Of these, 300,000 were in Russia which,

gripped by revolution and civil war, had little interest in their fate. Nansen

was able to report to the Assembly in November 1920 that around 200,000

men had been returned to their homes. "Never in my life", he said,

"have I been brought into touch with so formidable an amount of

suffering." Nansen

continued this work for a further two years until, in his final report

to the Assembly in 1922, he was able to state that 427,886 prisoners

had been repatriated to around 30 different countries. In paying

tribute to his work, the responsible committee recorded that the story

of his efforts "would contain tales of heroic endeavour worthy of those

in the accounts of the crossing of Greenland and the great Arctic

voyage." Even

before this work was complete, Nansen was involved in a further

humanitarian effort. On 1 September 1921, prompted by the British delegate Philip Noel-Baker, he accepted the post of the League's High Commissioner for Refugees. His main brief was the resettlement of around two million Russian refugees displaced by the upheavals of the Russian Revolution.

At the same time he tried to tackle the urgent problem of famine in

Russia; following a widespread failure of crops around 30 million

people were threatened with starvation and death. Despite Nansen's

pleas on behalf of the starving, Russia's revolutionary government was

feared and distrusted internationally, and the League was reluctant to

come to its peoples' aid. Nansen had to rely largely on fundraising from private organisations, and his efforts met with limited success. Later he was to express himself bitterly on the matter: There

was in various transatlantic countries such an abundance of maize ...

that the farmers ... had to burn it as fuel in their railway engines.

At the same time the ships in Europe were idle, for there were no

cargoes. Simultaneously there were thousands, nay millions of

unemployed. All this, while thirty million people in the Volga

region — not far away and easily reached by our ships — were allowed to

starve and die. A

major problem impeding Nansen's work on behalf of refugees was that

most of them lacked documentary proof of identity or nationality.

Without legal status in their country of refuge, their lack of papers

meant they were unable to go anywhere else. To overcome this, Nansen

devised a document that became known as the "Nansen passport",

a form of identity for stateless persons that was in time recognised by

more than 50 governments, and which allowed refugees to cross borders

legally. Among the more distinguished holders of Nansen passports were

the artist Marc Chagall, the composer Igor Stravinsky, and the dancer Anna Pavlova. Although the passport was created initially for refugees from Russia, it was extended to cover other groups. After the Greco - Turkish wars of 1919 – 1922 Nansen travelled to Constantinople to

negotiate the resettlement of hundreds of thousands of refugees, mainly

ethnic Greeks who had fled from Turkey after the defeat of the Greek

Army. The impoverished Greek state was unable to take them in, and

so Nansen devised a scheme for a population exchange whereby half a

million Turks in Greece were returned to Turkey, with full financial

compensation, while further loans facilitated the absorption of the

refugee Greeks into their homeland. Despite some controversy over the principle of a population exchange, the plan was implemented successfully over a period of several years. In November 1922, while attending the Conference of Lausanne, Nansen learned that he had been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for

1922. The citation referred to "his work for the repatriation of the

prisoners of war, his work for the Russian refugees, his work to bring

succour to the millions of Russians afflicted by famine, and finally

his present work for the refugees in Asia Minor and Thrace". Nansen donated the prize money to international relief efforts. From 1925 onwards he spent much time trying to help Armenian refugees, victims of massacres at the hands of the Ottoman Empire during the First World War and further ill-treatment thereafter. His goal was the establishment of a national home for these refugees, within the borders of Soviet Armenia. His main assistant in this endeavour was Vidkun Quisling, the future Nazi collaborator and head of a Norwegian puppet government during the Second World War. After visiting the region, Nansen presented the Assembly with a modest plan for the irrigation of 36,000 hectares (360 km2 or 139 square miles) on which 15,000 refugees could be settled. The

plan ultimately failed, because even with Nansen's unremitting advocacy

the money to finance the scheme was not forthcoming. Despite this

failure, his reputation among the Armenian people remains high. Within

the League's Assembly, Nansen spoke out on many issues besides those

related to refugees. He believed that the Assembly gave the smaller

countries such as Norway a "unique opportunity for speaking in the

councils of the world." He believed that the extent of the League's success in reducing armaments would be the greatest test of its credibility. He was a signatory to the Slavery Convention of 25 September 1926, which sought to outlaw the use of forced labour. He supported a settlement of the post-war reparations issue,

and championed Germany's membership of the League, which was granted in

September 1926 after intensive preparatory work by Nansen. On

17 January 1919 Nansen married Sigrun Munthe, a long-time friend with

whom he had had a love affair in 1905, while Eva was still alive. The

marriage was resented by the Nansen children, and proved unhappy; an

acquaintance writing of them in the 1920s said Nansen appeared

unbearably miserable and Sigrun steeped in hate. Nansen's

League of Nations commitments through the 1920s meant that he was

mostly absent from Norway, and was able to devote little time to

scientific work. Nevertheless, he continued to publish occasional

papers. He entertained the hope that he might travel to the North Pole by airship, but could not raise sufficient funding. In any event he was forestalled in this ambition by Amundsen, who flew over the pole in Umberto Nobile's airship Norge in May 1926. Two

years later Nansen broadcast a memorial oration to Amundsen, who had

disappeared in the Arctic while organising a rescue party for Nobile

whose airship had crashed during a second polar voyage. Nansen said of

Amundsen: "He found an unknown grave under the clear sky of the icy

world, with the whirring of the wings of eternity through space." In 1926 Nansen was elected Rector of the University of St Andrews in

Scotland, the first foreigner to hold this largely honorary position.

He used the occasion of his inaugural address to review his life and

philosophy, and to deliver a call to the youth of the next generation.

He ended: We

all have a Land of Beyond to seek in our life — what more can we ask? Our

part is to find the trail that leads to it. A long trail, a hard trail,

maybe; but the call comes to us, and we have to go. Rooted deep in the

nature of every one of us is the spirit of adventure, the call of the

wild — vibrating under all our actions, making life deeper and higher and

nobler. Nansen

largely avoided involvement in domestic Norwegian politics, but in 1924

he was persuaded by the long retired former prime minister Christian

Michelsen to lend his name to a new anti-communist political grouping, Fædrelandslaget ("Fatherland League"). There were fears in Norway that should the Marxist orientated Norwegian Labour Party gain power it would introduce a revolutionary programme. At a Fædrelandslaget rally

in Oslo (as Christiania had now been renamed), Nansen declared: "To

talk of the right of revolution in a society with full civil liberty,

universal suffrage, equal treatment for everyone ... [is] idiotic

nonsense." Although members of the movement advocated a Nansen-led

National government, the idea gained little public or political support. In

between his various duties and responsibilities, Nansen had continued

to take skiing holidays when he could. In February 1930, aged 68, he

took a short break in the mountains with two old friends, who noted

that Nansen was slower than usual and appeared to tire easily. On his

return to Oslo he was laid up for several months, with influenza and

later phlebitis, and was visited on his sickbed by King Haakon.

Nansen died of a heart attack, at home, on 13 May 1930. He was given a state funeral before

cremation, after which his ashes were laid under a tree at

Polhøgda. Nansen's daughter Liv recorded that there were no

speeches, just music: Schubert's Death and the Maiden, which Eva used to sing. Among the many tributes paid to him subsequently was that of Lord Robert Cecil,

a fellow League of Nations delegate, who spoke of the range of Nansen's

work, done with no regard for his own interests or health: "Every good

cause had his support. He was a fearless peacemaker, a friend of

justice, an advocate always for the weak and suffering." Nansen

had been a pioneer and innovator in many fields. As a young man he

embraced the revolution in skiing methods that transformed it from a

means of winter travel to a universal sport, and quickly became one of

Norway's leading skiers. He was later able to apply this expertise to

the problems of polar travel, in both his Greenland and his Fram expeditions.

He invented the "Nansen sledge" with broad, ski-like runners, the

"Nansen cooker" to improve the heat efficiency of the standard spirit

stoves then in use, and the layer principle in polar clothing, whereby

the traditionally heavy, awkward garments were replaced by layers of

lightweight material. In science, Nansen is recognised both as one of

the founders of modern neurology, and as a significant contributor to early oceanographical science. Through

his work on behalf of the League of Nations, Nansen helped to establish

the principle of international responsibility for refugees. Immediately after his death the League set up the Nansen International Office for Refugees,

a semi autonomous body under the League's authority, to continue his

work. The Nansen Office faced great difficulties, in part arising from

the large numbers of refugees from the European dictatorships during

the 1930s. Nevertheless it secured the agreement of 14 countries (including a reluctant Great Britain) to the Refugee Convention of 1933. It also helped to repatriate 10,000 Armenians to Yerevan in

Soviet Armenia, and to find homes for a further 40,000 in Syria and

Lebanon. In 1938, the year in which it was superseded by a

wider ranging body, the Nansen Office was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. In 1954 the League's successor body, the United Nations, established the Nansen Medal,

later named the Nansen Refugee Award, given annually to an individual

or organisation "in recognition of extraordinary and dedicated service

to refugees". In his lifetime and thereafter, Nansen received honours and recognition from many countries. Numerous geographical features are named after him: the Nansen Basin and the Nansen-Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic Ocean; Mount Nansen in the Yukon region of Canada; Mount Nansen, Mount Fridtjof Nansen and Nansen Island, all in Antarctica. Polhøgda is now home to the Fridtjof Nansen Institute, an independent foundation which engages in research on environmental, energy and resource management politics. In 1968 a film of Nansen's life, Bare et liv – Historien om Fridtjof Nansen was released, directed by Sergei Mikaelyen, with Knut Wigert as Nansen. In 2004 the Royal Norwegian Navy launched the first of a series of five Nansen Class anti-submarine warfare frigates. The lead ship of the group is HNoMS Fridtjof Nansen; two others are named after Roald Amundsen and Otto Sverdrup.

At

first Nansen and Johansen made good progress south, but on 13 April

suffered a serious setback when both of their watches stopped. Without

knowing the correct time, it was impossible for them to calculate their

longitude and thus navigate their way accurately to Franz Josef Land.

They restarted the watches on the basis of Nansen's guess that they

were at longitude 86°E, but from then on were uncertain of their

true position. Towards the end of April they observed the tracks of an Arctic fox, the first trace they had seen of a living creature other than their dogs since leaving Fram. Soon

they began to see bear tracks, and by the end of May seals, gulls and

whales were in evidence. On 31 May, by Nansen's calculations, they were

only 50 nautical miles (93 km; 58 mi) from Cape Fligely, the northernmost known point of Franz Josef Land. However,

travel conditions worsened as the warmer weather caused the ice to

break up. On 22 June the pair decided to rest on a stable ice floe while

they repaired their equipment and gathered their strength for the next

stage of their journey. They remained on the floe for a month. The

day after leaving this camp Nansen recorded: "At last the marvel has

come to pass — land, land, and after we had almost given up our belief in

it!" Whether this still-distant land was Franz Josef Land or a new discovery they

did not know — they had only a rough sketch map to guide them. On

6 August they reached the edge of the ice, where they shot the last of

their dogs — they had been killing the weakest regularly since 24 April,

to feed the others. They then lashed their two kayaks together, raised

a sail and made for the land.