<Back to Index>

- Explorer Salomon August Andrée, 1854

- Poet Giambattista Marino, 1569

- Prime Minister of Italy Ivanoe Bonomi, 1873

PAGE SPONSOR

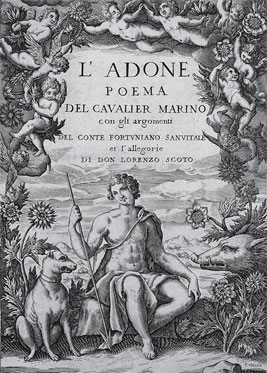

Giambattista Marino (also Giovan Battista Marino) (18 October 1569 – 25 March 1625) was an Italian poet who was born in Naples. He is most famous for his long epic L'Adone.

The Cambridge History of Italian Literature thought him to be "one of the greatest Italian poets of all time". He is considered the founder of the school of Marinism, later called Secentismo, characterised by its use of extravagant and excessive conceits. Marino's conception of poetry, which exaggerated the artificiality of Mannerism, was based on an extensive use of antithesis and a whole range of wordplay, on lavish descriptions and a sensuous musicality of the verse, and enjoyed immense success in his time, comparable to that of Petrarch before him.

He was widely imitated in Italy, France (where he was the idol of members of the précieux school, such as Georges Scudéry, and the so-called libertins such as Tristan l'Hermite), Spain (where his greatest admirer was Lope de Vega) and other Catholic countries, including Portugal and Poland, as well as Germany, where his closest follower was Christian Hoffmann von Hoffmannswaldau. In England he was admired by John Milton and translated by Richard Crashaw.

He

remained the reference point for Baroque poetry as long as it was in

vogue. In the 18th and 19th centuries, while being remembered for

historical reasons, he was regarded as the source and exemplar of

Baroque "bad taste". With the 20th century renaissance of interest in

similar poetic procedures his work has been reevaluated: it was closely

read by Benedetto Croce and

Carlo Calcaterra and has had numerous important interpreters including

Giovanni Pozzi, Marziano Guglielminetti, Marzio Pieri and Alessandro Martini. Marino remained in his birthplace Naples until

1600, leading a life of pleasure after breaking off relations with his

father who wanted his son to follow a career in law. These formative

years in Naples were very important for the development of his poetry,

even though most of his career took place in the north of Italy and

France. Regarding this subject, some critics (including Giovanni Pozzi)

have stressed the great influence on him exerted by northern Italian

cultural circles; others (such as Marzio Pieri) have emphasised the

fact that the Naples of the time, though partly in decline and

oppressed by Spanish rule, was far from having lost its eminent

position among the capitals of Europe. Marino's father was a highly cultured lawyer, from a family probably of Calabrian origin, who frequented the coterie of Giambattista Della Porta.

It seems that both Marino and his father took part in private

theatrical performances of their host's plays at the house of the Della

Porta brothers. But

more importantly, these surroundings put Marino in direct contact with

the natural philosophy of Della Porta and the philosophical systems of Giordano Bruno and Tommaso Campanella.

While Campanella himself was to oppose "Marinism" (though not attacking

it directly), this common speculative background should be borne in

mind with its important pantheistic (and

thus neo-pagan and heterodox) implications, to which Marino would

remain true all his life and exploit in his poetry, obtaining great

success amongst some of the most conformist thinkers on the one hand

while encountering continual difficulties because of the intellectual

content of his work on the other. Other figures who were particularly influential on the young Marino include Camillo Pellegrini, who had been a friend of Torquato Tasso (Marino

knew Tasso personally, if only briefly, at the house of Giovan Battista

Manso and exchanged sonnets with him). Pellegrini was the author of Il Carrafa overo della epica poesia, a dialogue in honour of Tasso, in which the latter was rated above Ludovico Ariosto. Marino himself is the protagonist of another of the prelate's dialogues, Del concetto poetico (1599). Marino

gave himself up to literary studies, love affairs and a life of

pleasure so unbridled that he was arrested at least twice. In this as

in many other ways, the path he took resembles that of another great

poet of the same era with whom he was often compared: Gabriello Chiabrera. But

an air of mystery surrounds Marino's life, especially the various times

he spent in prison; one of the arrests was due to procuring an abortion

for a certain Antonella Testa, daughter of the mayor of Naples, but

whether she was pregnant by Marino or one of his friends is unknown;

the second conviction (for which he risked a capital sentence) was due

to the poet's forging episcopal bulls in order to save a friend who had

been involved in a duel. But

some witnesses, who include both Marino's detractors (such as Tommaso

Stigliani) and defenders (such as the printer and biographer Antonio

Bulifoni in a life of the poet which appeared in 1699) have firmly

asserted that Marino, much of whose love poetry is heavily ambiguous,

had homosexual tendencies. Elsewhere, the reticence of the sources on

this subject is obviously due to the persecutions to which "sodomitical

practices" were particularly subject during the Counterreformation. Marino

then fled Naples and moved to Rome, first joining the service of

Melchiore Crescenzio, then that of Cardinal Aldobrandini. In 1608 he

moved to the court of Duke Carlo Emanuele I in Turin. This was not an easy time for the poet, in fact he was the victim of an assassination attempt by his rival Gaspare Murtola and he was then sentenced to a year in prison for malicious gossip he had written about the duke. In 1615 he left Turin and moved to Paris,

where he remained until 1623, honoured by the court and admired by

French literary circles. He returned to Italy in triumph and died in

Naples in 1625.