<Back to Index>

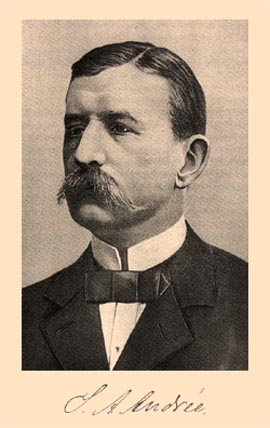

- Explorer Salomon August Andrée, 1854

- Poet Giambattista Marino, 1569

- Prime Minister of Italy Ivanoe Bonomi, 1873

PAGE SPONSOR

Salomon August Andrée (October 18, 1854 – October 1897), during his lifetime most often known as S.A. Andrée, was a Swedish engineer, physicist, aeronaut and polar explorer, who perished while leading an attempt to reach the Geographic North Pole by hydrogen balloon. Although unique, the balloon expedition was ultimately unsuccessful in reaching the Pole and resulted in the deaths of all three of its participants.

Andrée was born in the small town of Gränna, Sweden; he was especially close to his mother, especially after the death of his father in 1870. He attended the Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering in 1874. In 1876 he went to the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where he was employed as a janitor at the Swedish Pavilion. During his trip to the United States he read a book on trade winds and met the American balloonist John Wise; these encounters initiated his life long fascination with balloon travel. He returned to Sweden and opened a machine shop where he worked until 1880; it was less than successful and he soon looked for other employment. From 1880 to 1882 he was an assistant at the Royal Institute of Technology, and in 1882 – 1883 he participated in a Swedish scientific expedition to Spitsbergen led by Nils Ekholm, where Andrée was responsible for the observations regarding air electricity. From 1885 to his death, he was employed by the Swedish patent office. From 1891 – 1894 he was also a liberal member of the Stockholm city council. As a scientist, Andrée published scientific journals about air electricity, conduction of heat, and inventions. His view of life was that of the natural sciences, and he entirely lacked interest in art or literature. He was a firm believer in industrial and technical development, and claimed also that emancipation of women would come as a consequence of technical progress.

Supported by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences and funded by people like King Oscar II and Alfred Nobel, his polar exploration project was the subject of enormous interest and was seen as a brave and patriotic scheme. The North Pole expedition made a first try to launch the balloon Örnen (The Eagle) in the summer of 1896 from Danskøn, an island in the west of the Svalbard Archipelago, but the winds did not permit the expedition to start. When Andrée next tried, on July 11, 1897, together with his companions engineer Knut Frænkel and photographer Nils Strindberg (a second cousin of playwright August Strindberg), the balloon did set off and sailed for 65 hours. This was not directed flight, however; already at the lift-off the gondola had lost two of the three sliding ropes that were supposed to drag on the ice and thus function as a kind of rudder (this was observed by the ground crew). And within ten hours of lift-off, they were caught by powerful winds from a storm raging in the area. The heavy winds continued and, together with the rain creating ice on the balloon, impeded the flight. It is likely that Andrée realized already before the flight ended that they would never come near the pole.

Due to these causes they were forced down on the ice, though the landing was conducted in a semi-controlled way rather than actually crashing. They had covered 295 miles (475 km) and floundered on the pack ice. The expedition was well equipped for traveling on the ice (3 sledges and a boat) and had supplies for three months plus three deposits in northern Svalbard and one in Frans Josef's Land. They set off eastbound for the latter but after a week they had moved west due to the currents which moved the ice. They then changed direction towards northern Svalbard; movement was continuously slowed down by ice drift and by the craggy surface of the pack ice. The three had to pull the sledges themselves, and despite good reserves of food, added to by their shooting down polar bears, the efforts against the moving, uneven ice wore them out.

They reached land in early October after over two months on the ice, setting foot on Kvitøya (White Island), just east of Svalbard. They perished there, probably within two weeks after landfall. Most modern writers agree that Nils Strindberg died within a week of arrival: he was buried, after a fashion, among the rocks (though no marking was set on his grave) while the other two men were later found in the tent.

Diary notes and observations end just a few days after they landed on Kvitöya; up to that point these had been vigorously kept up even in hard conditions; this seems to indicate that something critical happened after a few days. Likely, Strindberg met his end at this point. The reason for his death has not been possible to establish. Suicide (which would have been possible with opium) is very unlikely in his case even though by this time all three no doubt realized they would die. Whatever Strindberg might have felt about the outcome of the expedition, it is near certain that he would have judged the option of suicide as treachery on his fellow explorers.

The diary notes of the expedition indicate that all three men were sometimes plagued by digestive trouble, illness and exhaustion during the trek over the sea ice. The ultimate cause of death was probably to do with the ingestion of polar bear flesh carrying Trichinella parasites, which were found in the remains of a polar bear on the spot examined by the Danish physician Ernst Tryde and published in a book in 1952 called "The Dead on White Island". There is no doubt that the men became infected at some point during the ice trek, though the exact time span is unclear (and this matters because humans normally develop immunity to trichinosis if they survive the first wave of infection). When they arrived at White Island they were suffering from recurrent diarrhea. A plausible indication of this is that some of the provisions they brought ashore (obviously after a few days of scouting to the west) were unloaded and left near the water and not carried to a safer place near the camp. The three bodies were cremated before the burial in Stockholm, unfortunately without any examination to find out the cause of death.

Until Andrée's last camp was found in 1930, what could have happened to the expedition was the subject of myth and rumours. In 1898, eleven months after Andrée's first sighting of White Island (which he called New Iceland) a Swedish polar expedition lead by A G Nathorst was passing by just 1 km off shore the camp, but the weather stopped them from getting ashore. Already around this time, it was noticed that a heavy storm had been raging and that the expedition had lost the steering lines at departure, and experienced polar explorers surmised already before 1930 that the expedition couldn't have got very far and had likely been forced down on the ice. Finally the remains of the three men were found in 1930 by the Norwegian Bratvaag Expedition which picked up remains including two bodies. A month later the ship M/K Isbjørn, hired by a newspaper, made additional finds, among them the third body. Several note books, diaries, photographic negatives, the boat and many utensils and other objects were recovered. The homecoming of the bodies of Andrée and his colleagues Strindberg and Frænkel was a grand event. King Gustaf V delivered an oration, and the explorers received a funeral with great honors. The three explorers were cremated and their ashes interred together at the cemetery Norra begravningsplatsen in Stockholm.

Starting in the 1960s, Andrée's status as a national hero has become questioned and turned into a cooler, more skeptic view, in a way not unlike the changing assessment of Robert Falcon Scott's South polar journey. The emphasis has been turned to the fact that the expedition was bound to fail, and that Andrée obviously refused to take in information that questioned the expedition's feasibility (and also had meagre actual flight experience with large balloons, and none in Arctic conditions). Andrée has been seen as a manipulator of the national emotions of his age, bringing a meaningless death on himself and his two companions. Several modern writers, following Sundman's Andrée portrait in the semi documentary novel The Flight of the Eagle ("Ingenjör Andrées luftfärd", 1967), have speculated that Andrée, by the time of the departure for Svalbard in 1897, had become the prisoner of his own successful funding campaign and the excited national feelings, and was now incapable of backing out or admitting weaknesses in the plans in front of the press.

Andrée's writings were adapted into the song cycle The Andrée Expedition by the American composer Dominick Argento, written for the Swedish baritone Håkan Hagegård. In 1982, the Swedish filmmaker Jan Troell directed a film based on Sundman's book, Flight of the Eagle.