<Back to Index>

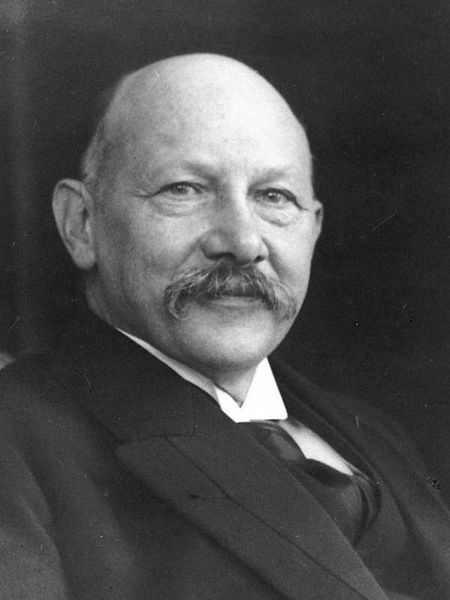

- Physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, 1853

- Painter Hans Hartung, 1904

- Sultan of the Ottoman Empire Abdul Hamid II, 1842

PAGE SPONSOR

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (21 September 1853 – 21 February 1926) was a Dutch physicist and Nobel laureate. He pioneered refrigeration techniques, and he explored how materials behaved when cooled to nearly absolute zero. He was the first to liquify helium. His production of extreme cryogenic temperatures led to his discovery of superconductivity in 1911: for certain materials, electrical resistance abruptly vanishes at very low temperatures.

Kamerlingh Onnes was born in Groningen, Netherlands. His father, Harm Kamerlingh Onnes, was a brickworks owner. His mother was Anna Gerdina Coers of Arnhem.

In 1870, Kamerlingh Onnes attended the University of Groningen. He studied under Robert Bunsen and Gustav Kirchhoff at the University of Heidelberg from 1871 to 1873. Again at Groningen, he obtained his masters in 1878 and a doctorate in 1879. His thesis was "Nieuwe bewijzen voor de aswenteling der aarde" (tr. New proofs of the rotation of the earth). From 1878 to 1882 he was assistant to Johannes Bosscha, the director of the TU Delft (then Delft Polytechnic), for whom he substituted as lecturer in 1881 and 1882.

From 1882 to 1923 Kamerlingh Onnes served as professor of experimental physics at the University of Leiden. In 1904 he founded a very large cryogenics laboratory and invited other researchers to the location, which made him highly regarded in the scientific community. In 1908, he was the first physicist to liquify helium, using the Hampson - Linde cycle and cryostats. Using the Joule - Thomson effect, he lowered the temperature to less than one degree above absolute zero, reaching 0.9 K. At the time this was the coldest temperature achieved on earth. The original equipment is at the Boerhaave Museum in Leiden.

He was married to Maria Adriana Wilhelmina Elisabeth Bijleveld (m. 1887) and had a child named Albert. Kamerlingh Onnes conducted (in 1911) electrical analysis of pure metals (mercury, tin and lead) at very low temperatures. Some, such as William Thomson (Lord Kelvin), believed that electrons flowing through a conductor would

come to a complete halt or, in other words, metal resistivity will

become infinity at absolute zero. Others, including Kamerlingh Onnes,

felt that a conductor's electrical resistance would steadily decrease and drop to nil. Augustus Matthiessen pointed

out when the temperature decreases, the metal conductivity usually

improves or in other words, the electrical resistivity usually

decreases with a decrease of temperature. At 4.2 kelvin the

resistance in a mercury column under test suddenly vanished. Kamerlingh

Onnes initially thought that the wiring to their test apparatus had

shorted out. It was only after changes in the experiment that he

realized that the effect was real. Kamerlingh Onnes stated that the "Mercury has passed into a new state, which on account of its extraordinary electrical properties may be called the superconductive state". He published more articles about the phenomenon, initially referring to it as "supraconductivity" and, only later adopting the term "superconductivity". Kamerlingh Onnes received widespread recognition for his work, including the 1913 Nobel Prize in Physics for (in the words of the committee) "his investigations on the properties of matter at low temperatures which led, inter alia, to the production of liquid helium". Some of the instruments he devised for his experiments can still be seen at the Boerhaave Museum in Leiden. The apparatus he used to first liquefy helium is on display in the lobby of the physics department at Leiden University, where the low temperature lab is also named in his honor. His student and successor as director of the lab Willem Hendrik Keesom was the first person who was able to solidify helium, in 1926. The Onnes effect referring to the creeping of superfluid Helium is named in his honor. The crater Kamerlingh Onnes on the Moon is named after him. Onnes is also credited with coining the word "enthalpy".