<Back to Index>

- Explorer Cornelis de Houtman, 1565

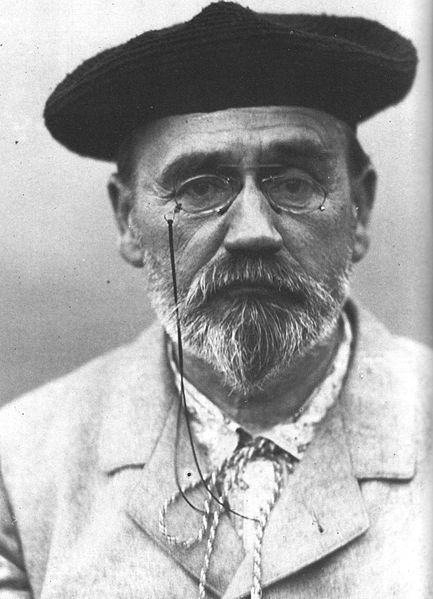

- Writer Émile François Zola, 1840

- Prime Minister of France Léon Gambetta, 1838

PAGE SPONSOR

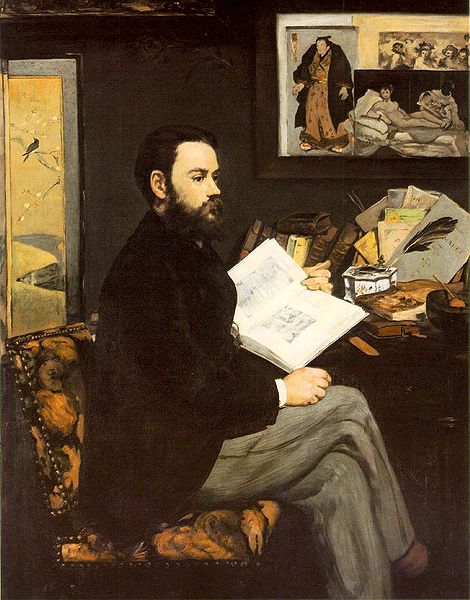

Émile François Zola (2 April 1840 – 29 September 1902) was a French writer, the most important exemplar of the literary school of naturalism and an important contributor to the development of theatrical naturalism. He was a major figure in the political liberalization of France and in the exoneration of the falsely accused and convicted army officer Alfred Dreyfus, which is encapsulated in the renowned newspaper headline J'Accuse.

Zola was born in Paris in 1840. His father, François Zola (originally Francesco Zolla), was an Italian engineer. With his French wife, Émilie Aurélie Aubert, the family moved to Aix-en-Provence, in the southeast, when he was three years old. Four years later, in 1847, his father died, leaving his mother on a meager pension. In 1858, the Zolas moved to Paris, where Émile's childhood friend the painter Paul Cézanne soon joined him. Zola started to write in the romantic style. His widowed mother had planned a law career for Émile, but he failed his Baccalauréat examination.

Before

his breakthrough as a writer, Zola worked as a clerk in a shipping

firm, and then in the sales department for a publisher (Hachette). He also wrote literary and art reviews for newspapers. As a political journalist, Zola did not hide his dislike of Napoleon III, who had successfully run for the office of President under the constitution of the French Second Republic, only to misuse this position as a springboard for the coup d'état that made him emperor. During

his early years, Émile Zola wrote several short stories and

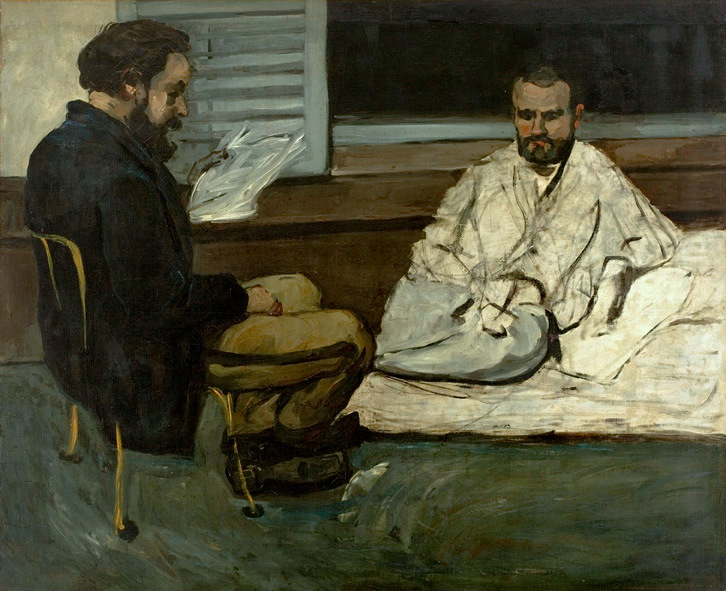

essays, four plays and three novels. Among his early books was Contes à Ninon, published in 1864. With the publication of his sordid autobiographical novel La Confession de Claude (1865) attracting police attention, Hachette fired him. His novel Les Mystères de Marseille appeared as a serialized story in 1867. After his first major novel, Thérèse Raquin (1867), Zola started the long series called Les Rougon Macquart, about a family under the Second Empire. In Paris, Zola maintained his friendship with Cézanne who painted a portrait of Zola with another friend from Aix-en-Provence writer Paul Alexis entitled Paul Alexis reading to Zola. More than half of Zola's novels were part of this set of 20 collectively known as Les Rougon-Macquart. Unlike Balzac who in the midst of his literary career resynthesized his work into La Comédie Humaine,

Zola from the outset at the age of 28 had thought of the complete

layout of the series. Set in France's Second Empire, the series traces

the "environmental" influences of violence, alcohol, and prostitution which became more prevalent during the second wave of the Industrial Revolution.

The series examines two branches of a single family: the respectable

(that is, legitimate) Rougons and the disreputable (illegitimate)

Macquarts, for five generations. As

he described his plans for the series, "I want to portray, at the

outset of a century of liberty and truth, a family that cannot restrain

itself in its rush to possess all the good things that progress is

making available and is derailed by its own momentum, the fatal

convulsions that accompany the birth of a new world." Although

Zola and Cézanne were friends from childhood and in youth, they

broke in later life over Zola's fictionalized depiction of

Cézanne and the Bohemian life of painters in his novel L'Œuvre (The Masterpiece, 1886). From 1877 onwards with the publication of l'Assommoir, Émile Zola became wealthy – he was better paid than Victor Hugo, for example. He became a figurehead among the literary bourgeoisie and organized cultural dinners with Guy de Maupassant, Joris-Karl Huysmans and other writers at his luxurious villa in Medan near Paris after 1880. Germinal in 1885, then the three 'cities', Lourdes in 1894, Rome in 1896 and Paris in 1897, established Zola as a successful author. The self-proclaimed leader of French naturalism, Zola's works inspired operas such as those of Gustave Charpentier, notably Louise in the 1890s. His works, inspired by the concepts of heredity (Claude Bernard), social manichaeism and idealistic socialism, resonate with those of Nadar, Manet and subsequently Flaubert. Captain

Alfred Dreyfus was a Jewish artillery officer in the French army. When

the French intelligence found information about someone giving the

German embassy military secrets, anti-semitism seems to have caused

senior officers to suspect Dreyfus, though there was no direct evidence

of any wrongdoing. Dreyfus was court-martialled, convicted of treason

and sent to Devil's Island in French Guiana. LL Col. Georges Picquart, though, came across evidence that implicated another officer, Ferdinand Walsin Esterhazy,

and informed his superiors. Rather than move to clear Dreyfus, the

decision was made to protect Esterhazy and ensure the original verdict

was not overturned. Major Hubert-Joseph Henry forged

documents that made it seem that Dreyfus was guilty and then had

Picquart assigned duty in Africa. Before leaving, Picquart told some of

Dreyfus's supporters what he knew. Soon Senator August Scheurer -

Kestner took up the case and announced in the Senate that Dreyfus was

innocent

and accused Esterhazy. The right wing government refused new evidence

to be allowed and Esterhazy was tried and acquitted. Picquart was then

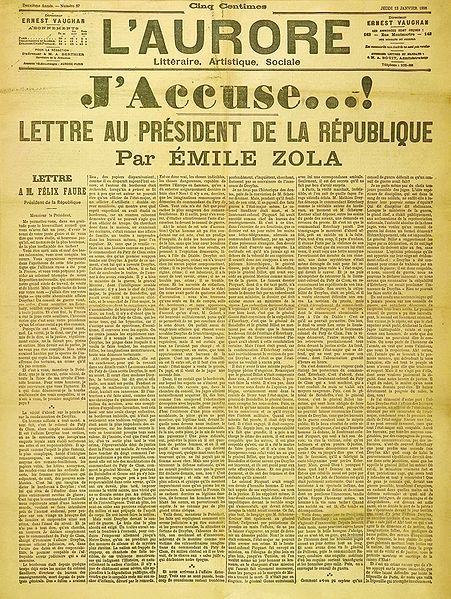

sentenced to 60 days in prison. Émile Zola risked his career and even his life on 13 January 1898, when his "J'accuse", was published on the front page of the Paris daily, L'Aurore. The newspaper was run by Ernest Vaughan and Georges Clemenceau, who decided that the controversial story would be in the form of an open letter to the President, Félix Faure. Émile Zola's "J'Accuse" accused the highest levels of the French Army of obstruction of justice and antisemitism by

having wrongfully convicted Alfred Dreyfus to life imprisonment on

Devil's Island. Zola declared that Dreyfus' conviction came after a

false accusation of espionage and was a miscarriage of justice. The

case, known as the Dreyfus affair, divided France deeply between the

reactionary army and church, and the more liberal commercial society.

The ramifications continued for many years; on the 100th anniversary of

Zola's article, France's Roman Catholic daily paper, La Croix, apologized for its antisemitic editorials

during the Dreyfus Affair. As Zola was a leading French thinker, his

letter formed a major turning point in the affair. Zola

was brought to trial for criminal libel on 7 February 1898, and was

convicted on 23 February, sentenced, and removed from the Legion of Honor. Rather than go to jail, Zola fled to England. Without even having had the time to pack a few clothes, he arrived at Victoria Station on 19 July. After his brief and unhappy residence in London, from October 1898 to June 1899, he was allowed to return in time to see the government fall. The

government offered Dreyfus a pardon (rather than exoneration), which he

could accept and go free and so effectively admit that he was guilty,

or face a re-trial in which he was sure to be convicted again. Although

he was clearly not guilty, he chose to accept the pardon. Emile Zola

said, "The truth is on the march, and nothing shall stop it." In 1906, Dreyfus was completely exonerated by the Supreme Court. The 1898 article by Émile Zola is widely marked in France as the most prominent manifestation of the new power of the intellectuals (writers, artists, academicians) in shaping public opinion, the media and the state.

Zola died of carbon monoxide poisoning caused

by a stopped chimney. He was 62 years old. His enemies were blamed

because of previous attempts on his life, but nothing could be proven.

(Decades later, a Parisian roofer claimed on his deathbed to have

closed the chimney for political reasons). Addresses

of sympathy arrived from all parts of France; for an entire week the

vestibule of his house was crowded with notable writers, scientists,

artists and politicians, who came to inscribe their names in the registers.

On the other hand, Zola's enemies used the opportunity to celebrate in

malicious glee. Thus, Henri Rochefort wrote a piece in "L'Intransigeant", claiming Zola had committed suicide, having discovered Dreyfus to be in fact guilty. Zola was initially buried in the Cimetière de Montmartre in Paris, but on 4 June 1908, almost six years after his death, his remains were moved to the Panthéon, where he shares a crypt with Victor Hugo and Alexandre Dumas. Zola’s 20 Rougon-Macquart novels are a panoramic account of the Second French Empire.

They are the story of a particular family, its branches and

descendants, principally between the years 1851 and 1871. These 20

novels contain over 300 major characters, who descend from the two

family lines of the Rougons and Macquarts and who are therefore, in one

way or another, interrelated. In Zola’s own words, which are the

subtitle of the Rougon-Macquart series, they are L’Histoire naturelle et sociale d’une famille sous le Second Empire. Almost all of the Rougon-Macquart novels were written during the French Third Republic and,

to some extent, attitudes and value judgments may have been

superimposed on to that picture with the wisdom of hindsight. The

débâcle in which the reign of Napoleon III of France culminated

may have imparted a note of decadence to certain of the novels dealing

with France in the years before that disastrous defeat. Nowhere is the

doom laden image of the Second Empire so clearly seen as in Nana, which itself culminates in echoes of the Franco - Prussian War (and

hence, by implication, of the French defeat). But even in novels

dealing with earlier periods of Napoleon III’s reign the picture of the

Second Empire is sometimes overlaid with the imagery of catastrophe. In

the Rougon-Macquart novels provincial life tends to be overshadowed by

Zola’s insistent preoccupation with the capital. Only in his picture of

rural working class life in La Terre, and in the corresponding picture of industrial working class life in Germinal,

does Zola convincingly escape from Paris into the provinces. The life

of provincial towns is an even more noticeable omission from his

achievement, for only in Le Rêve and

in the twice repeated picture of Plassans – modeled upon his childhood

home, Aix-en-Provence – does he achieve such a portrait (La Fortune des Rougon, La Conquête de Plassans); Le Docteur Pascal has the same setting but cannot properly be termed a novel of provincial life. La Débâcle,

the military novel set for the most part in country districts of

eastern France, is certainly not a novel of provincial life in the

accepted sense of the term; its dénouement takes place in the

battle scarred capital of the Paris Commune. Like Balzac’s,

but to an even greater extent than was the case with his mentor, Zola’s

creative imagination was roused by Paris and all that the capital

represented to him symbolically.

In Le Roman expérimental and Les Romanciers naturalistes Zola

expounds what he claims to be the essential purposes of the Naturalist

novel. The main purpose of the experimental novel was, in his view, to

serve as a vehicle for scientific experiment analogous to the

scientific experimentation already conducted by Claude Bernard and expounded by the latter in his Introduction à la médecine expérimentale. But whereas Claude Bernard’s experiments were in the field of clinical physiology, those of the Naturalist writers – Zola being their leader – would be in the realm of psychology. Balzac, Zola claimed, had already investigated the psychology of lechery in an experimental manner in the figure of Hector Hulot in La Cousine Bette.

Essential to Zola’s concept of the experimental novel was the key role

of sober dispassionate observation of the world, with all that that

involved by way of solid meticulous documentation. Each novel, Zola

believed, should be based upon a carefully prepared dossier. With this

object in view he visited the colliery of Anzin, in northern France, in February 1884, when a strike was in progress; he likewise visited La Beauce (for La Terre), Sedan, Ardennes (for La Débâcle), and travelled on the railway line between Paris and Le Havre (when documenting himself for La Bête humaine). However, Zola did sometimes profess his awareness that the work of any creative artist must by its very nature be subjective. For

a writer who so strongly asserted the claim of Naturalist literature to

be an experimental analysis of human psychology, Zola has seemed to

many critics, including György Lukács, to

be strangely deficient in the power of creating life-like and memorable

characters. These critics admit his ability to evoke powerful and

moving crowd scenes, but argue that he lacked both the ability to

create memorable characters, in the manner of Honoré de Balzac or Charles Dickens,

and likewise the ability to make his characters true to life. It was,

of course, a central article of Zola’s literary faith that no character

should appear larger than life; but

the criticism that Zola’s characters are mere cardboard figures, and

not true to life, is an infinitely more damaging one, and one which, in

view of the characterization of Gervaise Macquart (L'Assommoir), Nana Coupeau (Nana), Jacques Lantier (La Bête humaine), Serge Mouret (La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret), Jean Macquart (La Terre) and Pascal Rougon (Le Docteur Pascal),

may seriously be doubted. Zola, by refusing to make any of his

characters larger than life (if that is what he has indeed done), did

not inhibit himself from also achieving verisimilitude. Although,

however, Zola would not accept that it was either scientifically or

artistically justifiable to create larger-than-life characters, his

work does present a number of larger-than-life symbols which, like the

mine Le Voreux in Germinal, take on the nature of a surrogate human life. The mine, and the still in L'Assommoir, and the locomotive La Lison in La Bête humaine impress

the reader with the vivid reality of human beings; likewise, the great

natural processes of seedtime and harvest, death and renewal in La Terre are instinct with a vitality which is not human but is the elemental energy of a life-force. Human life is raised to the level of the mythical as the hammerblows of Titans are seemingly heard underground at Le Voreux, or as, in La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret, the walled park of Le Paradou encloses a re-enactment – and restatement – of the myth of the Book of Genesis. This is the visionary aspect of the Rougon - Macquart series. “For

a vivid, impartial picture – on the whole a faithful picture – of

certain of the most characteristic aspects of this period, seen indeed

from the outside, but drawn by a contemporary in all its intimate and

even repulsive details, the reader of a future age can best go to Zola”. This

comment underlines the historical nature of the Rougon-Macquart novels,

the accuracy of their picture of contemporary life, both Parisian and

to some extent provincial. However, it is also suggested by Havelock Ellis that

Zola achieves no more than a superficial fidelity to the truth: he does

not, on this view, explore the hidden workings of society, nor does he

lay bare the secret motive forces which keep that society in being. Zola’s

claims to be regarded as a historian or a clinical psychologist are

therefore open to serious question. Although he must be credited with

an intuition of the imminent importance of the science of psychology,

he has not in any scientific way advanced our knowledge of human

nature. The subjective nature of his own experimentation was something

of which he was only vaguely aware. As a historian, too, he seems to

fall short of a proper scientific objectivity in his handling of his

subject matter. The personal preoccupations of his own life are

superimposed on to the supposedly “objective”, “dispassionate” raw

material of history. This

process occurs both thematically and at the level of imagery,

particularly in the leitmotifs of love and death. Thematically, the

linking of love and death is seen in the final mine scene in Germinal, or in Jacques Lantier’s pathological urge (in La Bête humaine)

to murder the women he loves. There are very few happy, fulfilled and

continuing love relationships in Zola’s work, where love is often the

harbinger of death. In La Faute de l’Abbé Mouret,

in the relationship of Serge and Albine, the symbolic intermingling of

love and death is carried to a high point of literary perfection. This

personal preoccupation of Zola is, therefore, dominant both in the more

and the less “realistic” of the Rougon-Macquart novels. In

Zola there is not merely the theorist and the imaginative writer, there

are also the poet and the scientist, and the optimist and the creator of “la littérature putride”, as one reviewer called it. The poet is the artist in words whose writing, as in the racecourse scene in Nana, or in the descriptions of the laundry in L'Assommoir, or in many passages of La Faute de l'Abbé Mouret, Le Ventre de Paris and La Curée, vies with the colourful impressionistic techniques of Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

The scientist is the believer in some measure of scientific determinism

– not that this, despite his own words “dépourvus de libre

arbitre”, need always amount to a philosophical denial of human free will. The creator of “la littérature putride”, a term of abuse invented by an early critic of Thérèse Raquin (a novel which predates Les Rougon-Macquart series), emphasizes the squalid aspects of the human environment and upon the seamy side of human nature. But

the optimist is that other face of the scientific experimenter, the man

with an unshakable belief in human progress. Zola bases his optimism on

two considerations: on innéité and on the supposed capacity of the human race to make progress in a moral sense. Innéitéis defined by Zola as that process in which “se confondent les

caractères physiques et moraux des parents, sans que rien d'eux

semble s’y retrouver”; it

is the term used in biology to describe the process whereby the moral

and temperamental dispositions of some individuals are unaffected by

the hereditary transmission of genetic characteristics. Jean Macquart

and Pascal Rougon are two instances of individuals liberated from the

blemishes of their ancestors by the operation of the process of innéité. Also especially evident in Le Docteur Pascal, and again in Fécondité (which

is not part of the Rougon-Macquart series), is Zola's conviction that

just as scientific research makes progress step by step and from

generation to generation, so by slow degrees but in a similarly steadfast manner the moral progress of the human race will be achieved as the environmental faults of particular societies are swept away, as (through innéité)

the hereditary failings of particular families are overcome, and as on

a universal scale – in novels beyond the framework of the

Rougon-Macquart series – humanity unites in brotherhood.