<Back to Index>

- Explorer Cornelis de Houtman, 1565

- Writer Émile François Zola, 1840

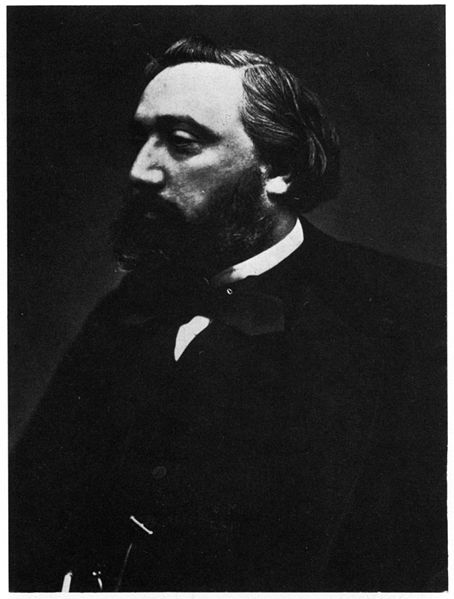

- Prime Minister of France Léon Gambetta, 1838

PAGE SPONSOR

Léon Gambetta (2 April 1838, Cahors — 31 December 1882, Sèvres) was a French statesman prominent after the Franco - Prussian War.

He is said to have inherited his vigour and eloquence from his father, a Genovese grocer who had married a Frenchwoman named Massabie. At the age of fifteen, Gambetta lost the sight of his left eye in an accident, and it eventually had to be removed. Despite this handicap, he distinguished himself at school in Cahors, and in 1857 went to Paris to study law. His southern temperament gave him great influence among the students of the Quartier Latin, and he was soon known as an inveterate enemy of the imperial government.

He was called to the bar in 1859, but, although contributing to a Liberal review, edited by Challemel-Lacour, did not make much of an impression until, on 17 November 1868, he was selected to defend the journalist Delescluze, prosecuted for having promoted a monument to the representative Baudin, who was killed while resisting the coup d'état of 1851. Gambetta seized his opportunity and attacked both the coup d'état and the government with a vigour which made him immediately famous.

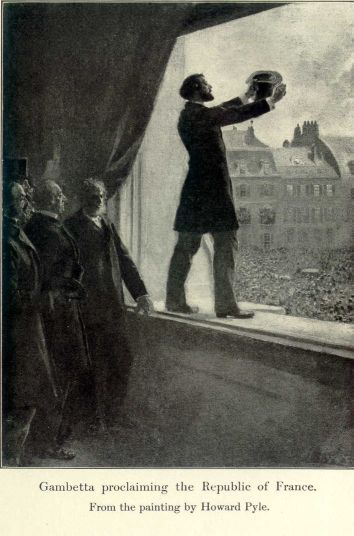

In May 1869, he was elected to the Assembly, both by a district in Paris and another in Marseille, defeating Hippolyte Carnot for the former constituency and Adolphe Thiers and Ferdinand de Lesseps for the latter. He chose to sit for Marseille, and lost no opportunity of attacking the Empire in the Assembly. At first opposed to the war with Germany, he did not, like some of his colleagues, refuse to vote for funds for the army, but took a patriotic line and accepted that the war had been forced on France. When the news of the disaster at Sedan reached Paris, Gambetta called for strong measures. He proclaimed the deposition of the emperor at the corps législatif, and the establishment of a republic at the Hôtel de Ville. He was one of the first members of the new Government of National Defense, becoming Minister of the Interior. He advised his colleagues to leave Paris and run the government from some provincial city.

This advice was rejected because of fear of another revolution in Paris, and a delegation to organize resistance in the provinces was despatched to Tours, but when this was seen to be ineffective, Gambetta himself (7 October) left Paris in a hot air balloon – the "Armand - Barbès" – and upon arriving at Tours took control as minister of the interior and of war. Aided by Freycinet, a young officer of engineers, as his assistant secretary of war, he displayed prodigious energy and intelligence. He quickly organized an army, which might have relieved Paris if Metz had held out, but Bazaine's surrender brought the army of the Prussian crown prince into the field, and success was impossible. After the French defeat near Orléans early in December the seat of government was transferred to Bordeaux.

Early in his political career, Gambetta was influenced by Le Programme de Belleville, the seventeen statutes that defined the radical program in French politics throughout the Third Republic. This made him the leading defender of the lower classes in the Corps Législatif. On (17 January) (1870), he spoke out against naming a new Imperial Lord

Privy Seal, putting him into direct conflict with the regime's de facto

prime minister, Emile Ollivier. (Reinach, J., Discours et Playdories de Léon Gambetta,

I.102 - 113) His powerful oratory caused a complete breakdown of order

in the Corps. The Monarchist Right continually tried to interrupt his

speech, only to have Gambetta's supporters on the Left attack them. The

disagreement reached a high point when M. le Président Schneider

asked him to bring his supporters back into order. Gambetta responded,

thundering "l'indignation exclut le calme!" (Reinach, Discours et Playdories, I.112) Gambetta

had hoped for a republican majority in the general elections on 8

February 1871. These hopes vanished when the conservatives and

Monarchists won nearly 2/3 of the six hundred Assembly seats. He had

won elections in eight different départements, but the ultimate victor was the Orléanist Adolphe Thiers,

winner of twenty-three elections. Thiers's conservative and bourgeois

intentions clashed with the growing expectations of political power by

the lower classes. Hoping to continue his policy of "guerre à

outrance" against the Prussian invaders, he tried in vain to rally the

Assembly to the war cause. However, Thiers' peace treaty on 1 March

1871 ended the conflict. Gambetta, disgusted with the Assembly's

unwillingness to fight resigned and quit France for San Sebastián in Spain. While in San Sebastián, Gambetta walked the beaches daily, the warm sea winds of early spring doing little to refresh his mind. Meanwhile the Paris Commune had taken control of the city. Despite his earlier career, Gambetta voiced his opposition to the Commune in a letter to Antonin Proust,

his former secretary while Minister of the Interior, in which he

referred to the Commune as "les horribles aventures dans lesquelles

s’engage ce qui reste de cette malheureuse France". Gambetta's

stance has been explained by reference to his status as a republican

lawyer, who fought from the bar instead of the barricade and also to his father having been a grocer in Marseille. As a small scale producer during the decades of the Second Industrial Revolution in

France, Joseph Gambetta had chain groceries taking business away from

his establishment. This added a measure of resentment to the "petit

bourgeois" identity. This resentment was not only directed at bourgeois

industrial capitalism, but also at the worker, who was now proclaimed

as the backbone of the French economy, stripping the title from the

small, independent shopkeeper. This

resentment may have been passed down from father to son, and manifested

itself in an unwillingness to support the lower class Communards

usurpation of what rightfully belonged to the "petit bourgeoisie". On 24 June 1871, a letter was sent by Gambetta to his Parisian confidant, Dr. Édouard Fieuzal: (Lettres de Gambetta, no. 122) Gambetta returned to the political stage and won on three separate ballots. On 5 November 1871 he established a journal, La Republique française,

which soon became the most influential in France. His orations at

public meetings were more effective than those delivered in the

Assembly, especially the one at Bordeaux. His turn towards moderate republicanism first became apparent in Firminy, a small coal-mining town along the Loire River. There, he boldly proclaimed the radical republic he once supported to be "avoided as a plague" (se tenir éloignés comme de la peste) (Discours, III.5). From there, he went to Grenoble. On 26 September 1872, he proclaimed the future of the Republic to be in the hands of "a new social level" (une couche sociale nouvelle) (Discours, III. 101), ostensibly the petite bourgeoisie to whom his father belonged. When Adolphe Thiers resigned in May 1873, and a Royalist, Marshal MacMahon,

was placed at the head of the government, Gambetta urged his friends to

a moderate course. By his tact, parliamentary dexterity and eloquence,

he was instrumental in voting in the French Constitutional Laws of 1875 in February 1875. He gave this policy the appropriate name of "opportunism," and became one of the leader of the "Opportunist Republicans". On 4 May 1877, he denounced "clericalism" as the enemy. During the 16 May 1877 crisis, Gambetta, in a speech at Lille on 15 August called on President MacMahon se soumettre ou se démettre,

to submit to parliament's majority or to resign. Gambetta then

campaigned to rouse the republican party throughout France, which

culminated in a speech at Romans (18 September 1878) formulating its

programme. MacMahon, unwilling to resign or to provoke civil war, had

no choice but to dismiss his advisers and form a moderate republican

ministry under the premiership of Dufaure. When

the downfall of the Dufaure cabinet brought about MacMahon's

resignation, Gambetta declined to become a candidate for the

presidency, but supported Jules Grévy;

nor did he attempt to form a ministry, but accepted the office of

president of the chamber of deputies in January 1879. This position did

not prevent his occasionally descending from the presidential chair to

make speeches, one of which, advocating an amnesty to the communards,

was especially memorable. Although he directed the policy of the

various ministries from behind the scenes, he evidently thought that

the time was not ripe for asserting openly his direction of the policy

of the Republic, and seemed inclined to observe a neutral attitude as

far as possible. However, events hurried him on, and early in 1881 he

headed off a movement for restoring scrutin de liste,

or the system by which deputies are returned by the entire department

which they represent, so that each elector votes for several

representatives at once, in place of scrutin d'arrondissement,

the system of small constituencies, giving one member to each district

and one vote to each elector. A bill to re-establish scrutin de liste

was passed by the Assembly on 19 May 1881, but rejected by the Senate

on 19 June. This

personal rebuff could not alter the fact that his name was on the lips

of voters at the election. His supporters won a large majority, and Jules Ferry's cabinet quickly resigned. Gambetta was unwillingly asked by Grévy on 24 November 1881 to form a ministry, known as Le Grand Ministère.

Many suspected him of desiring a dictatorship; unjust attacks were

directed against him from all sides, and his cabinet fell on 26 January

1882, after only sixty-six days. Had he remained in office, he would

have cultivated the British alliance and cooperated with Britain in

Egypt; and when the succeeding Freycinet government

shrank from that enterprise only to see it undertaken with signal

success by Britain alone, Gambetta's foresight was quickly justified. On 31 December 1882, at his house in Ville d'Avray, near Sèvres, he was killed by an accidental discharge from a revolver. Five artists, Jules Bastien-Lepage, a realist painter, Antonin Proust, defensor of the vanguard who Gambetta had named Minister of Beaux-Arts, Léon Bonnat, an academic painter, Alexandre Falguière, who did his mortuary mask, and his personal photographer Étienne Carjat all

sat at his death-bed, making five widely different representations of

him which were each published by the press the following day. His public funeral on 6 January 1883 evoked one of the most overwhelming displays of national sentiment ever witnessed. Gambetta

rendered France three inestimable services: by preserving her

self-respect through the gallantry of the resistance he organized during the German War,

by his tact in persuading extreme partisans to accept a moderate

Republic, and by his energy in overcoming the usurpation attempted by

the advisers of Marshal MacMahon. His death at forty-four cut short a

career which had given promise of still greater things, for he had real

statesmanship in his conceptions of the future of his country, and he

had an eloquence which would have been potent in the education of his

supporters. The romance of his life was his connection with Léonie Leon,

the full details of which were not known to the public till her death

in 1906. She was the daughter of a French artillery officer. Gambetta

fell in love with her in 1871. She became his mistress, and the liaison

lasted until he died. Gambetta constantly urged her to marry him during

this period, but she always refused, fearing to compromise his career;

she remained, however, his confidante and intimate adviser in all his

political plans. It seems she had just consented to become his wife,

and the date of the marriage had been fixed, when the accident which

caused his death occurred in her presence. Contradictory accounts of

this fatal episode exist, but it was certainly accidental, and not suicide.

Her influence on Gambetta was absorbing, both as lover and as

politician, and the correspondence which has been published shows how

much he depended upon her. However,

some of her later recollections are untrustworthy. For example, she

claimed that an actual interview took place in 1878 between Gambetta

and Bismarck. That Gambetta after 1875 felt strongly that the relations

between France and Germany might he improved, and that he made it his

object, by travelling incognito, to become better acquainted with

Germany and the adjoining states, may be accepted, but M. Laur appears

to have exaggerated the extent to which any actual negotiations took

place. On the other hand, the increased knowledge of Gambetta's

attitude towards European politics which later information has supplied

confirms the view that in him France lost prematurely a master mind,

whom she could ill spare. In April 1905 a monument by Dalou to his memory at Bordeaux was unveiled by President Loubet.