<Back to Index>

- Mathematician Charles Hutton, 1737

- Painter Pieter Coecke van Aelst, 1502

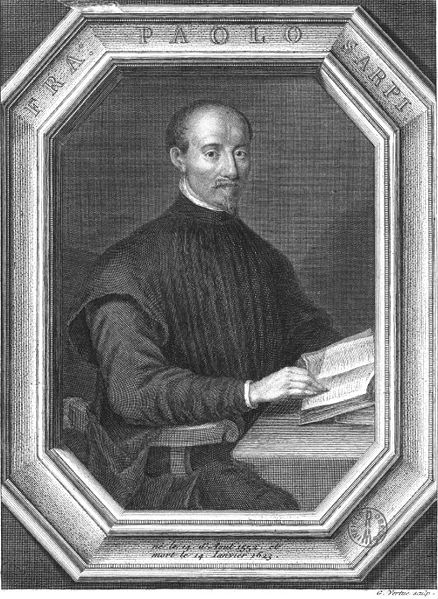

- Venetian Patriot Paolo Sarpi, 1552

PAGE SPONSOR

Paolo Sarpi (August 14, 1552 – January 15, 1623) was a Venetian patriot, scholar, scientist and church reformer. His most important roles were as a canon lawyer and historian active on behalf of the Venetian Republic.

He was born Pietro Sarpi in Venice, the son of a tradesman, but was orphaned at an early age. He was educated by his maternal uncle and then Giammaria Capella, a Servite monk. Ignoring the opposition of his remaining family, he entered the Servite order in 1566. He assumed the name of Paolo, by which, with the epithet Servita, he was always known to his contemporaries.

In 1570 he sustained 318 theses at a disputation in Mantua, and was so applauded that the Duke of Mantua made him court theologian. Sarpi spent four years at Mantua, studying mathematics and the Oriental languages. He then went to Milan in 1575, where he enjoyed the protection of Cardinal Borromeo to whom he was an adviser; but was soon transferred by his superiors to Venice, as professor of philosophy at the Servite convent. In 1579, he was sent to Rome on business connected with the reform of his order, which brought him into close contact with three successive popes, as well as the grand inquisitor and other influential people.

Having

completed the task entrusted to him, he returned to Venice in 1588, and

passed the next seventeen years in study, occasionally interrupted by

the need to intervene in the internal disputes of his community. In

1601, he was recommended by the Venetian senate for the small bishopric of Caorle, but the papal nuncio, who wished to obtain it for a protégé of his own, accused Sarpi of having denied the immortality of the soul and controverted the authority of Aristotle. An attempt to obtain another small bishopric in the following year also failed, Pope Clement VIII having taken offence at Sarpi's habit of corresponding with learned heretics. Clement died in March 1605, and the attitude of his successor Pope Paul V strained

the limits of papal prerogative. Venice simultaneously adopted measures

to restrict it: the right of the secular tribunals to take cognizance

of the offences of ecclesiastics had been asserted in two leading

cases, and the scope of two ancient laws of the city, forbidding the

foundation of churches or ecclesiastical congregations without the

consent of the state, and the acquisition of property by priests or

religious bodies, had been extended over the entire territory of the

republic. In January 1606, the papal nuncio delivered a brief demanding

the unconditional submission of the Venetians. The senate promised

protection to all ecclesiastics who should in this emergency aid the

republic by their counsel. Sarpi presented a memoir, pointing out that

the threatened censures might be met in two ways -- de facto, by prohibiting their publication, and de jure, by an appeal to a general council. The document was well received, and Sarpi was made canonist and theological counsellor to the republic. The following April, hopes of compromise were dispelled by Paul's excommunication of

the Venetians and his attempt to lay their dominions under an

interdict. Sarpi entered energetically into the controversy. It was

unprecedented for an ecclesiastic of his eminence to argue the

subjection of the clergy to the state. He began by republishing the anti-papal opinions of the canonist Jean Gerson. In an anonymous tract published shortly afterwards (Risposta di un Dottore in Teologia), he laid down principles which struck radically at papal authority in secular matters. This book was promptly included in the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, and Gerson's work was attacked by Bellarmine with severity. Sarpi then replied in an Apologia. The Considerazioni sulle censure and the Trattato dell' interdetto,

the latter partly prepared under his direction by other theologians,

soon followed. Numerous other pamphlets appeared, inspired or

controlled by Sarpi, who had received the further appointment of censor

of everything written at Venice in defence of the republic. The Venetian clergy largely disregarded the interdict, and discharged their functions as usual, the major exception being the Jesuits who left, and were simulataneously expelled officially. The Catholic powers France and Spain refused to be drawn into the quarrel, but resorted to diplomacy. At

length (April 1607), a compromise was arranged through the mediation of

the king of France, which salvaged the pope's dignity, but conceded the

points at issue. The victory was not so much the defeat of the papal

pretensions as the recognition that interdicts and excommunication had

lost their force. The

republic rewarded him with the distinction of state counsellor in

jurisprudence and the liberty of access to the state archives. These

honours exasperated his adversaries. On October 5, he was attacked by assassins and

left for dead, but he recovered. His attackers found a refuge in the

papal territories. Their chief, Poma, declared that he had attempted

the murder for religious reasons. "Agnosco stylum Curiae Romanae,"

Sarpi himself said, when his surgeon commented on the ragged and

inartistic character of the wounds. The only question is the degree of

complicity of Pope Paul V. The remainder of Sarpi's life was spent peacefully in his cloister,

though plots against him continued to be formed, and he occasionally

spoke of taking refuge in England. When not engaged in preparing state

papers, he devoted himself to scientific studies, and composed several

works. He served the Venetian state to the last. The day before his

death, he had dictated three replies to questions on affairs of state,

and his last words were "Esto perpetua." In 1619 his chief literary work Istoria del Concilio Tridentino (History of the Council of Trent),

was printed at London. It appeared under the name of Pietro Soave

Polano, an anagram of Paolo Sarpi Veneto (plus o). The editor, Marco Antonio de Dominis,

did some work on polishing the text. He has been accused of falsifying

it, but a comparison with a manuscript corrected by Sarpi himself shows

that the alterations are unimportant. Translations into other languages

followed: there were the English translation by Nathaniel Brent and a Latin edition in 1620 made partly by Adam Newton, and French and German editions. Its emphasis was on the role of the Papal Curia,

and its slant on the Curia hostile. This was unofficial history, rather

than a commission, and treated ecclesiastical history as politics. This attitude, "bitterly realistic" for John Hale, was coupled with a criticism, that the Tridentine settlement was not concilatory but designed for further conflict. Denys Hay calls it "a kind of Anglican picture of the debates and decisions", and Sarpi was much read by Protestants; John Milton called him the "great unmasker". This book, together with the later rival and apologetic history by Cardinal Pallavicini, was criticized by Leopold von Ranke (History of the Popes),

who examined the use they have respectively made of their manuscript

materials. The result was not highly favourable to either: without

deliberate falsification, both coloured and suppressed. They write as

advocates rather than historians. Ranke rated the literary qualities of

Sarpi's work very highly. Sarpi never acknowledged his authorship, and

baffled all the efforts of Louis II de Bourbon, Prince de Condé, to extract the secret from him. In 1615, a dispute occurred between the Venetian government and the Inquisition over the prohibition of a book. In 1613 the Senate had asked Sarpi to write about the history and procedure of the Venetian Inquisition. He argued that this had been set up in 1289, but as a Venetian state institution. The pope of the time, Nicholas IV, had merely consented to its creation. A Machiavellian tract on the fundamental maxims of Venetian policy (Opinione come debba governarsi la repubblica di Venezia), used by his adversaries to blacken his memory, dates from 1681. He did not complete a reply which he had been ordered to prepare to the Squitinio delia libertà veneta, which he perhaps found unanswerable. In folio appeared his History of Ecclesiastical Benefices, in which, says Matteo Ricci,

"he purged the church of the defilement introduced by spurious

decretals." In 1611, he assailed another abuse by his treatise on the

right of asylum claimed for churches, which was immediately placed on

the Index. His posthumous History of the Interdict was

printed at Venice the year after his death, with the disguised imprint

of Lyon. Sarpi's memoirs on state affairs remained in the Venetian

archives. The British Museum has a collection of tracts in the Interdict controversy, formed by Consul Smith. Griselini's Memorie e aneddote (1760) is from the author's access to Sarpi's unpublished writings, afterwards destroyed by fire. Early

letter collections were: "Lettere Italiane di Fra Sarpi" (Geneva,

1673); Scelte lettere inedite de P. Sarpi", edited by Bianchi - Giovini

(Capolago, 1833); "Lettere raccolte di Sarpi", edited by Polidori

(Florence, 1863); "Lettere inedite di Sarpi a S. Contarini", edited by

Castellani (Venice, 1892). Some hitherto unpublished letters of Sarpi were edited by Karl Benrath and published, under the title Paolo Sarpi. Neue Briefe, 1608 - 1610 (at Leipzig in 1909). A modern edition (1961) Lettere ai Gallicane has been published of his hundreds of letters to French correspondents. These are mainly to jurists: Jacques Auguste de Thou, Jacques Lechassier, Jacques Gillot. Another correspondent was William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Devonshire; English translations by Thomas Hobbes of

45 letters to the Earl were published (Hobbes acted as the Earl's

secretary), and it is now thought that these are jointly from Sarpi

(when alive) and his close friend Fulgenzio Micanzio, something concealed at the time as a matter of prudence. Micanzio was also in touch with Dudley Carleton, 1st Viscount Dorchester. Giusto Fontanini's Storia arcana della vita di Pietro Sarpi (1863), a bitter libel, is important for the letters of Sarpi it contains. He read and was influenced by both Michel de Montaigne and Pierre Charron. In the tradition of earlier Tacitists as

historian and sceptical thinker, he innovated in political thought, by

his emphasis that patriotism as national pride or honour could play a

central role in social control. In

religion, he was certainly suspected of a lack of orthodoxy: he

appeared before the Inquisition around 1575, in 1594, and in 1607. Sarpi

longed for the toleration of Protestant worship in Venice, and he had

hoped for a separation from Rome and the establishment of a Venetian

free church by which the decrees of the council of Trent would have

been rejected. Sarpi's real beliefs and motives are discussed in the

letters of Christoph von Dohna, envoy to Venice for Christian I, Prince of Anhalt - Bernburg. Sarpi told Dohna that he greatly disliked saying Mass,

and celebrated it as seldom as possible, but that he was compelled to

do so, as he would otherwise seem to admit the validity of the papal

prohibition, and thus betray the cause of Venice. This

supplies the key to his whole behaviour; he was a patriot first and a

religious reformer afterwards. He was "rooted" in what Giovanni Diodati described

to Dohna as "the most dangerous maxim, that God does not regard

externals so long as the mind and heart are right before Him." Sarpi had another maxim, which he thus formulated to Dohna: Le falsità non dico mai mai, ma la verità non a ognuno. Though Sarpi admired the English prayer-book, he was neither Anglican, Lutheran nor Calvinist, and might have found it difficult to accommodate himself to any Protestant church. The opinion of Le Courayer,

"qu'il était Catholique en gros et quelque fois Protestant en

détail" (that he was Catholic overall and sometimes Protestant

in detail) is partially true if approximate. At the end of his life,

however, he favoured the Calvinist Contra - Remonstrants' side at the Synod of Dort, as he wrote to Daniel Heinsius. Finally, Diarmaid MacCulloch suggests, he may have moved away from dogmatic Christianity. He was also respected by the scientific community of his day. He wrote notes on François Viète which established his proficiency in mathematics, and a metaphysical treatise now lost, which is said to have anticipated the ideas of John Locke. His anatomical pursuits

probably date from an earlier period. They illustrate his versatility

and thirst for knowledge, but are otherwise not significant. His claim

to have anticipated William Harvey's discovery rests on no better authority than a memorandum, probably copied from Andreas Caesalpinus or Harvey himself, with whom, as well as with Francis Bacon and William Gilbert, Sarpi corresponded. The only physiological discovery which can be safely attributed to him is that of the contractility of the iris. Galileo corresponded with him; Sarpi heard of the telescope in

November 1608, possibly before Galileo. In 1609 the Venetian Republic

had a telescope on approval for military purposes, but Sarpi had them

turn it down, anticipating the better model Galileo had made and

brought later in the year. Sarpi's

life was written by his disciple, Fulgenzio Micanzio, whose work is

meagre and uncritical. In the nineteenth century there were many

biographies, including that by Arabella Georgina Campbell (1869), with references to manuscripts, Pietro Balan, Fra Paolo Sarpi (Venice, 1887) and Pascolato, Fra Paolo Sarpi (Milan, 1893). A

contemporary account of Sarpi's writings on religion that argues for

his historical importance as a philosophical atheist is found in David Wootton's Paolo Sarpi: Between Renaissance and Enlightenment (Cambridge, 1983).