<Back to Index>

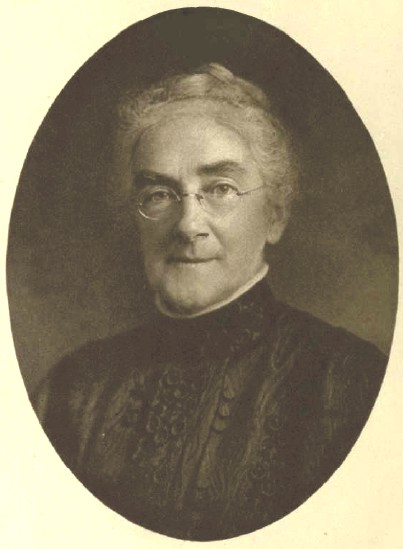

- Chemist Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards, 1842

- Writer Ludvig Holberg, 1684

- King of France Charles VI, 1368

PAGE SPONSOR

Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards (December 3, 1842 – March 30, 1911) was the foremost female industrial and environmental chemist in the United States in the 19th century, pioneering the field of home economics. Richards graduated from Westford Academy (2nd oldest secondary school in Westford, MA). She was the first woman admitted to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and its first female instructor, the first woman in America accepted to any school of science and technology, and the first American woman to earn a degree in chemistry.

Richards was a "pragmatic" feminist, as well as a founding "ecofeminist" who believed that women's work within the home was a vital aspect of the economy.

Born (to Fanny Taylor and Peter Swallow) to an old Dunstable, Massachusetts, family

of modest means which prized education, she was the first woman

admitted to MIT. Ellen Swallow taught, tutored, and cleaned for years,

finally saving $300 to enter Vassar College in

1868, earning her bachelor's degree two years later. After failing to

find suitable employment as an industrial chemist after graduation, she

entered MIT to continue her studies, "it being understood that her

admission did not establish a precedent for the general admission of

females" according to the records of the meeting of the MIT Corporation on December 14, 1870. Three

years later she received a Bachelor of Science degree from MIT for her

thesis "Notes on Some Sulpharsenites and Sulphantimonites from

Colorado," as

well as a Master of Arts degree from Vassar for a thesis on the

chemical analysis of iron ore. She continued her studies at MIT and

would have been awarded its first doctoral degree, but MIT balked at

granting this distinction to a woman, and did not award its first

doctorate until 1886.

In 1875 Ellen Swallow married Robert H. Richards, chairman of the Mine Engineering Department at MIT. With his support she remained associated with MIT, volunteering her services as well as contributing $1,000 annually to create programs for female students. In January 1876, she began a long association as an instructor with the first American correspondence school, the Society to Encourage Studies at Home. Also in 1876, with the urging of the Women's Education Association of Boston, the MIT Women's Laboratory was created, where in 1879 she became an assistant instructor (without pay) in the fields of chemical analysis, industrial chemistry, mineralogy, and applied biology, under Professor John M. Ordway. In 1883, MIT began accepting women and awarding them degrees as regular students, and the Laboratory was closed.

From 1884 until her death, Ellen Richards was an instructor in the newly founded laboratory of sanitary chemistry, the Lawrence Experiment Station, which was the first in the United States and headed by her former professor William R. Nichols. In 1887, the laboratory, then under Thomas Messinger Drown, conducted a study under Richards of water quality in Massachusetts for the Massachusetts State Board of Health involving

over 20,000 samples, the first such study in America. As a result,

Massachusetts established the first water quality standards in America,

as well as the first modern sewage treatment plant, in Lowell, Massachusetts.

Richards was a consulting chemist for the Massachusetts State Board of Health from 1872 to 1875, and the official water analyst from 1887 until 1897. She also served as a consultant to the Manufacturers Mutual Fire Insurance Co, and in 1900 wrote the textbook Air, Water, and Food from a Sanitary Standpoint, with A.G. Woodman. Her interest in the environment led her in 1892 to introduce into English the word ecology which had been coined in German to describe the "household of nature".

Richards' interests also included applying scientific principles to domestic situations, such as nutrition, clothing, physical fitness, sanitation, and efficient home management, creating the field of home economics. "Perhaps the fact that I am not a Radical and that I do not scorn womanly duties but claim it as a privilege to clean up and sort of supervise the room and sew things is winning me stronger allies than anything else", she wrote to her parents. She published The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning: A Manual for House - keepers in 1881, designed and demonstrated model kitchens, devised curricula, and organized conferences. In 1908, she was chosen to be the first president of the newly formed American Home Economics Association. Her books and writings on this topic include Food Materials and their Adulterations (1886), Conservation by Sanitation, The Chemistry of Cooking and Cleaning, The Cost of Living (1899), Air, Water, and Food (1900), The Cost of Food, The Cost of Shelter, The Art of Right Living, The Cost of Cleanness, Sanitation in Daily Life (1907), and Euthenics, the Science of Controllable Environment (1910). Some of these went through several editions.

Richards along with Marion Talbot (Boston University, class of 1880), became the initial "founding mothers" of what was to become the American Association of University Women when they invited 15 other women college graduates to a meeting at Talbot's home in Boston, Massachusetts on November 28, 1881. The 17 women envisioned an organization in which women college graduates would band together to open the doors of higher education to other women and to find wider opportunities for their training. AAUW became one of the nation's leading advocates for education and equity for all women and girls — a 125 year legacy of leadership. Today AAUW numbers more than 100,000 members, 1,300 branches, and 500 college and university partners nationwide.

Richards served on the Board of Trustees of Vassar College for many years, and was granted an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 1910. She died at Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts, in 1911. In her honor, MIT designated a room in the main buildings for the use of women students, and in 1973, on the occasion of the hundredth anniversary of Richard's graduation, established the Ellen Swallow Richards Professorship for distinguished female faculty members. Her data was used to find causes of pollution and improper sewage disposal.