<Back to Index>

- Philosopher Feng Yu-Lan, 1895

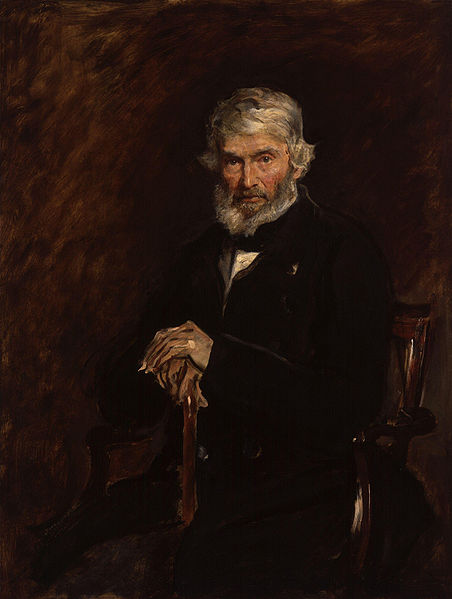

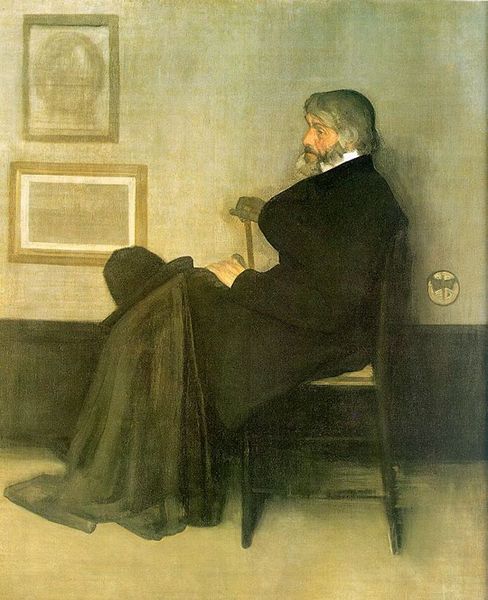

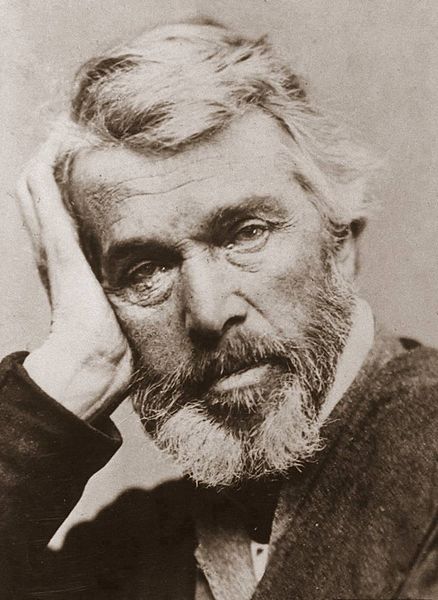

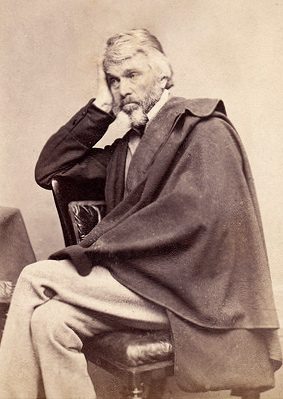

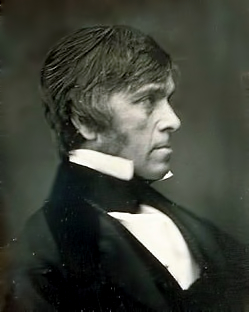

- Writer Thomas Carlyle, 1795

- 8th President of India Ramaswamy Venkataraman, 1910

PAGE SPONSOR

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 1795 – 5 February 1881) was a Scottish satirical writer, essayist, historian and teacher during the Victorian era. He called economics "the dismal science", wrote articles for the Edinburgh Encyclopedia, and became a controversial social commentator.

Coming from a strict Calvinist family, Carlyle was expected to become a preacher by his parents, but while at the University of Edinburgh, he lost his Christian faith. Calvinist values, however, remained with

him throughout his life. This combination, of a religious temperament

with loss of faith in traditional Christianity, made Carlyle's work

appealing to many Victorians who were grappling with scientific and

political changes that threatened the traditional social order.

Carlyle was born in Ecclefechan, Dumfries and Galloway. His parents determinedly afforded him an education at Annan Academy, Annan, where he was bullied and tormented so much that he left after three years. In early life, his family's (and his nation's) strong Calvinist beliefs powerfully influenced the young man.

After attending the University of Edinburgh, Carlyle became a mathematics teacher, first in Annan and then in Kirkcaldy, where Carlyle became close friends with the mystic Edward Irving. (Confusingly, there is another Scottish Thomas Carlyle, born a few years later and also connected to Irving, through his work with the Catholic Apostolic Church.)

In 1819 – 1821, Carlyle returned to the University of Edinburgh, where he suffered an intense crisis of faith and conversion that would provide the material for Sartor Resartus ("The Tailor Retailored"), which first brought him to the public's notice.

Carlyle developed a painful stomach ailment, possibly gastric ulcers (which pseudo - medicine of the time attributed to this "crisis of faith"), that remained throughout his life and contributed to his reputation as a crotchety, argumentative, and somewhat disagreeable personality. His prose style, famously cranky and occasionally savage, helped cement a reputation of irascibility.

He began reading deeply in German literature. Carlyle's thinking was heavily influenced by German Idealism, in particular the work of Johann Gottlieb Fichte. He established himself as an expert on German literature in a series of essays for Fraser's Magazine, and by translating German writers, notably Goethe (the novel Wilhelm Meisters Lehrjahre). He also wrote Life of Schiller (1825).

In 1826, Thomas Carlyle married Jane Baillie Welsh, herself a writer, whom he had met in 1821, during his period of German studies.

His home in residence for much of his early life, after 1828, was a farm in Craigenputtock, a house in Dumfrieshire, Scotland, where he wrote many of his works. He often wrote about his life at Craigenputtock, "It is certain that for living and thinking in I have never since found in the world a place so favourable.... How blessed, might poor mortals be in the straitest circumstances if their wisdom and fidelity to heaven and to one another were adequately great!".

At the Craigenputtock farm, Carlyle also wrote some of his most distinguished essays, and he began a lifelong friendship with the American essayist Ralph Waldo Emerson. In 1834, Carlyle moved to the Chelsea, London, section of London, where he was then known as the "Sage of Chelsea" and became a member of a literary circle which included the essayists Leigh Hunt and John Stuart Mill.

In London, Carlyle wrote The French Revolution: A History (3 volumes, 1837), as a historical study concerning oppression of the poor, which was immediately successful. That was the start of many other writings in London.

By

1821, Carlyle had abandoned the clergy as a career and focused on

making a life as a writer. His first attempt at fiction was "Cruthers

and Jonson", one of several abortive attempts at writing a novel.

Following his work on a translation of Goethe's Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship, he

came to distrust the form of the realistic novel and so worked on

developing a new form of fiction. In addition to his essays on German

literature, he branched out into wider ranging commentary on modern

culture in his influential essays Signs of the Times and Characteristics.

His first major work, Sartor Resartus was begun in 1831 at his home (provided for him by his wife Jane Welsh, from her estate), Craigenputtock, and was intended to be a new kind of book: simultaneously factual and fictional, serious and satirical, speculative and historical. It ironically commented on its own formal structure, while forcing the reader to confront the problem of where 'truth' is to be found. Sartor Resartus ("The Tailor Retailored") was first published periodically in Fraser's Magazine from 1833 to 1834. The text presents itself as an unnamed editor's attempt to introduce the British public to Diogenes Teufelsdröckh, a German philosopher of clothes, who is in fact a fictional creation of Carlyle's. The Editor is struck with admiration, but for the most part is confounded by Teufelsdröckh's outlandish philosophy, of which the Editor translates choice selections. To try to make sense of Teufelsdröckh's philosophy, the Editor tries to piece together a biography, but with limited success. Underneath the German philosopher's seemingly ridiculous statements, there are mordant attacks on Utilitarianism and the commercialization of British society. The fragmentary biography of Teufelsdröckh that the Editor recovers from a chaotic mass of documents reveals the philosopher's spiritual journey. He develops a contempt for the corrupt condition of modern life. He contemplates the "Everlasting No" of refusal, comes to the "Centre of Indifference", and eventually embraces the "Everlasting Yea". This voyage from denial to disengagement to volition would later be described as part of the existentialist awakening.

Given the enigmatic nature of Sartor Resartus, it is not surprising that

it was first received with little success. Its popularity developed

over the next few years, and it was published in book form in Boston

1836, with a preface by Ralph Waldo Emerson, influencing the development of New England Transcendentalism. The first English edition followed in 1838.

In 1834, Carlyle moved to London from Craigenputtock and began to move among celebrated company. Within the United Kingdom, Carlyle's success was assured by the publication of his three volume work The French Revolution: A History in 1837. After the completed manuscript of the first volume was accidentally burned by the philosopher John Stuart Mill's maid, Carlyle wrote the second and third volumes before rewriting the first from scratch. The resulting work was filled with a passionate intensity, hitherto unknown in historical writing. In a politically charged Europe, filled with fears and hopes of revolution, Carlyle's account of the motivations and urges that inspired the events in France seemed powerfully relevant. Carlyle's style of writing emphasised this, continually stressing the immediacy of the action – often using the present tense.

For Carlyle, chaotic events demanded what he called 'heroes' to take control over the competing forces erupting within society. While not denying the importance of economic and practical explanations for events, he saw these forces as 'spiritual' – the hopes and aspirations of people that took the form of ideas, and were often ossified into ideologies ("formulas" or "isms", as he called them). In Carlyle's view, only dynamic individuals could master events and direct these spiritual energies effectively: as soon as ideological 'formulas' replaced heroic human action, society became dehumanised.

On a side note, Victorian writer Charles Dickens used Carlyle's work as a primary source for the events of the French Revolution in his novel A Tale of Two Cities.

These ideas were influential on the development of Socialism, but — like the opinions of many deep thinkers of the time — are also considered to have influenced the rise of Fascism.

Carlyle moved towards his later thinking during the 1840s, leading to a

break with many old friends and allies, such as Mill and, to a lesser

extent, Emerson. His belief in the importance of heroic leadership found form in his book "On Heroes, Hero - Worship, and the Heroic in History", in which he compared a wide range of different types of heroes, including Odin, Oliver Cromwell, Napoleon, William Shakespeare, Dante, Samuel Johnson, Jean - Jacques Rousseau, Robert Burns, John Knox, Martin Luther and the Prophet Muhammad.

The book was based on a course of lectures he had given. The French Revolution had brought Carlyle fame, but little money. His friends worked to set him on his feet by organizing courses of public lectures for him, drumming up an audience and selling guinea tickets. Between 1837 and 1840, Carlyle delivered four such courses. The final course was on “Heroes.” From the notes he had prepared for this course, he wrote out his book, reproducing the curious effects of the spoken discourses.

The Hero as Man of Letters (Quotes):

- "In books lies the soul of the whole Past Time; the articulate audible voice of the Past, when the body and material substance of it has altogether vanished like a dream."

- "A man lives by believing something; not by debating and arguing about many things."

- "All that mankind has done, thought, gained or been: it is lying as in magic preservation in the pages of books."

- "What we become depends on what we read after all of the professors have finished with us. The greatest university of all is a collection of books."

- "The suffering man ought really to consume his own smoke; there is no good in emitting smoke till you have made it into fire."

- "Adversity is sometimes hard upon a man; but for one man who can stand prosperity, there are a hundred that will stand adversity." (Often shortened to "can't stand prosperity" as an unknown quote.)

- "Not what I have, but what I do, is my kingdom."

Carlyle was one of the very few philosophers who witnessed the industrial revolution but still kept a transcendental non - materialistic view of the world. The book included people ranging from the field of Religion through to literature and politics. He included people as coordinates and accorded Muhammad a special place in the book under the chapter title "Hero as a Prophet". In his work, Carlyle declared his admiration with a passionate championship of Muhammad as a Hegelian agent of reform, insisting on his sincerity and commenting ‘how one man single - handedly, could weld warring tribes and wandering Bedouins into a most powerful and civilized nation in less than two decades.’ For Carlyle the hero was somewhat similar to Aristotle's "Magnanimous" man — a person who flourished in the fullest sense. However, for Carlyle, unlike Aristotle, the world was filled with contradictions with which the hero had to deal. All heroes will be flawed. Their heroism lay in their creative energy in the face of these difficulties, not in their moral perfection. To sneer at such a person for their failings is the philosophy of those who seek comfort in the conventional. Carlyle called this 'valetism', from the expression 'no man is a hero to his valet.

All these books were influential in their day, especially on writers such as Charles Dickens and John Ruskin. However, after the Revolutions of 1848 and political agitations in the United Kingdom, Carlyle published a collection of essays entitled "Latter - Day Pamphlets" (1850) in which he attacked democracy as an absurd social ideal, while equally condemning hereditary aristocratic leadership. The latter was deadening, the former nonsensical: as though truth could be discovered by totting up votes. Government should come from those most able. But how we were to recognise the ablest, and to follow their lead, was something Carlyle could not clearly say.

In later writings Carlyle sought to examine instances of heroic leadership in history. The Letters and Speeches of Oliver Cromwell (1845) presented a positive image of Cromwell:

someone who attempted to weld order from the conflicting forces of

reform in his own day. Carlyle sought to make Cromwell's words live in

their own terms by quoting him directly, and then commenting on the

significance of these words in the troubled context of the time. Again

this was intended to make the 'past' 'present' to his readers.

The Everlasting Yea is Carlyle's name for the spirit of faith in God in an express attitude of clear, resolute, steady, and uncompromising antagonism to the Everlasting No, and the principle that there is no such thing as faith in God except in such antagonism against the spirit opposed to God. The Everlasting No is Carlyle's name for the spirit of unbelief in God, especially as it manifested itself in his own, or rather Teufelsdröckh's, warfare against it; the spirit, which, as embodied in the Mephistopheles of Goethe, is for ever denying, — der stets verneint — the reality of the divine in the thoughts, the character, and the life of humanity, and has a malicious pleasure in scoffing at everything high and noble as hollow and void.

In Sartor Resartus, the narrator moves from the "Everlasting No" to the "Everlasting Yea," but only through "The Center of Indifference," which is a position not merely of agnosticism, but also of detachment. Only after reducing desires and certainty and aiming at a Buddha - like "indifference" can the narrator move toward an affirmation. In some ways, this is similar to the contemporary philosopher Søren Kierkegaard's "leap of faith" in Concluding Unscientific Postscript.

In regards to the abovementioned "antagonism," one might note that William Blake famously wrote that "without contraries is no progression," and Carlyle's progress from the everlasting nay to the everlasting yea was not to be found in the "Centre of Indifference" (as he called it) but in Natural Supernaturalism, a Transcendental philosophy of the divine within the everyday.

Based on Goethe's having described Christianity as the "Worship of Sorrow", and "our highest religion, for the Son of Man", Carlyle adds, interpreting this, "there is no noble crown, well worn or even ill worn, but is a crown of thorns".

The

"Worship of Silence" is Carlyle's name for the sacred respect for

restraint in speech till "thought has silently matured itself, … to hold

one's tongue till some meaning lie behind to set it wagging," a

doctrine which many misunderstand, almost wilfully, it would seem;

silence being to him the very womb out of which all great things are

born.

His last major work was the epic life of Frederick the Great (1858 – 1865). In this Carlyle tried to show how a heroic leader can forge a state, and help create a new moral culture for a nation. For Carlyle, Frederick epitomized the transition from the liberal Enlightenment ideals of the eighteenth century to a new modern culture of spiritual dynamism: embodied by Germany, its thought and its polity. The book is most famous for its vivid, arguably very biased, portrayal of Frederick's battles, in which Carlyle communicated his vision of almost overwhelming chaos mastered by leadership of genius.

Carlyle called the work his “Thirteen Years War” with Frederick. In 1852, he made his first trip to Germany to gather material, visiting the scenes of Frederick's battles and noting their topography. He made another trip to Germany to study battlefields in 1858. The work comprised six volumes; the first two volumes appeared in 1858, the third in 1862, the fourth in 1864 and the last two in 1865. Emerson considered it “Infinitely the wittiest book that was ever written.” Lowell pointed out some faults, but wrote: “The figures of most historians seem like dolls stuffed with bran, whose whole substance runs out through any hole that criticism may tear in them; but Carlyle's are so real in comparison, that, if you prick them, they bleed.” The work was studied as a textbook in the military academies of Germany.

The effort involved in the writing of the book took its toll on Carlyle, who became increasingly depressed, and subject to various probably psychosomatic ailments. Its mixed reception also contributed to Carlyle's decreased literary output.

Later writings were generally short essays, often indicating the hardening of Carlyle's political positions. His notoriously racist essay "Occasional Discourse on the Negro Question" suggested that slavery should never have been abolished, or else replaced with serfdom. It had kept order, he argued, and forced work from people who would otherwise have been lazy and feckless. This – and Carlyle's support for the repressive measures of Governor Edward Eyre in Jamaica – further alienated him from his old liberal allies. Eyre had been accused of brutal lynchings while suppressing a rebellion. Carlyle set up a committee to defend Eyre, while Mill organised for his prosecution.

Carlyle had a number of would-be romances before he married Jane Welsh, important as a literary figure in her own right. The most notable were with Margaret Gordon, a pupil of his friend Edward Irving. Even after he met Jane, he became enamoured of Kitty Kirkpatrick, the daughter of a British officer and an Indian princess. William Dalrymple, author of White Mughals,

suggests that feelings were mutual, but social circumstances made the

marriage impossible, as Carlyle was then poor. Both Margaret and Kitty

have been suggested as the original of "Blumine", Teufelsdröch's

beloved, in Sartor Resartus.

Carlyle married Jane Welsh in 1826, making the marriage one of the most famous, well documented, and unhappy of literary unions. Over 9000 letters between Carlyle and his wife have been published showing the couple had an affection for one another marred by frequent and angry quarrels.

It was very good of God to let Carlyle and Mrs Carlyle marry one another, and so make only two people miserable and not four.

He had been introduced to Welsh by his friend and her tutor Edward Irving, with whom she came to have a mutual romantic (although not sexually intimate) attraction. Carlyle became increasingly alienated from his wife. Although she had been an invalid for some time, her death (1866) came unexpectedly and plunged him into despair, during which he wrote his highly self critical "Reminiscences of Jane Welsh Carlyle", published posthumously.

After Jane Carlyle's death in the year 1866, Thomas Carlyle partly retired from active society. He was appointed rector of the University of Edinburgh. The Early Kings of Norway: Also an Essay on the Portraits of John Knox appeared in 1875. His last years were spent at 24 Cheyne Row (then numbered 5), Chelsea, London SW3 (which is now a National Trust property commemorating his life and works) but he always wished to return to Craigenputtock.

Upon Carlyle's death on 5 February 1881 in London, it was made possible for his remains to be interred in Westminster Abbey, but his wish to be buried beside his parents in Ecclefechan was respected.

Carlyle

would have preferred that no biography of him were written, but when he

heard that his wishes would not be respected and that several people

were only waiting for him to die before they published, he relented and

began to supply his friend James Anthony Froude with many of his and his wife's papers. Carlyle's essay about his wife, Reminiscences of Jane Welsh Carlyle, was published after his death by Froude, who also published the Letters and Memorials of Jane Welsh Carlyle annotated by Carlyle himself. Froude's Life of Carlyle was

published over 1882 - 84. The frankness of this book was unheard of by

the usually respectful standards of 19th century biographies of the

period. Froude's work was attacked by Carlyle's family, especially his

nephew, Alexander Carlyle and his niece, Margaret Aitken Carlyle.

However, the biography in question was consistent with Carlyle's own

conviction that the flaws of heroes should be openly discussed, without

diminishing their achievements. Froude, who had been designated by

Carlyle himself as his biographer - to - be, was acutely aware of this

belief. Froude's defence of his decision, My Relations With Carlyle was

published posthumously in 1903, including a reprint of Carlyle's 1873

will, in which Carlyle equivocated: "Express biography of me I had

really rather that there should be none." Nevertheless, Carlyle in the

will simultaneously and completely deferred to Froude's judgement on

the matter, whose "decision is to be taken as mine."

Thomas Carlyle is notable both for his continuation of older traditions of the Tory satirists of the 18th century in England and for forging a new tradition of Victorian era criticism of progress known as sage writing. Sartor Resartus can be seen both as an extension of the chaotic, sceptical satires of Jonathan Swift and Laurence Sterne and as an enunciation of a new point of view on values. Finding the world hollow, Carlyle's misanthropist professor - narrator discovers a need for revolution of the spirit. In one sense, this resolution is in keeping with the Romantic era's belief in revolution, individualism, and passion, but in another sense it is a nihilistic and private solution to the problems of modern life that makes no gesture of outreach to a wider community.

Later British critics and sage writers, such as Matthew Arnold, would similarly denounce the mob and the naïve claims of progress, and others, such as John Ruskin, would reject the era's incessant move toward industrial production. However, few would follow Carlyle into a narrow and solitary resolution, and even those who would come to praise heroes would not be as remorseless for the weak.

Carlyle is also important for helping to introduce German Romantic literature to Britain. Although Samuel Taylor Coleridge had also been a proponent of Schiller, Carlyle's efforts on behalf of Schiller and Goethe would bear fruit.

Carlyle also made a favourable impression on some slaveholders in the U.S. South. His conservatism and criticisms of capitalism were enthusiastically repeated by those anxious to defend slavery as an alternative to capitalism, such as George Fitzhugh.

The reputation of Carlyle's early work remained high during the 19th century, but declined in the 20th century. His reputation in Germany was always high, because of his promotion of German thought and his biography of Frederick the Great. Friedrich Nietzsche, whose ideas are comparable to Carlyle's in some respects, was dismissive of his moralism, calling him an "insipid muddlehead" in Beyond Good and Evil and regarded him as a thinker who failed to free himself from the very petty - mindedness he professed to condemn. Carlyle's distaste for democracy and his belief in charismatic leadership was unsurprisingly appealing to Adolf Hitler, who was reading Carlyle's biography of Frederick during his last days in 1945.

This association with fascism did Carlyle's reputation no good in the post war years, but "Sartor Resartus" has recently been recognised once more as a unique masterpiece, anticipating many major philosophical and cultural developments, from Existentialism to Postmodernism. It has also been argued that his critique of ideological formulas in "The French Revolution" provides a good account of the ways in which revolutionary cultures turn into repressive dogmatisms.

Essentially a Romantic,

Carlyle attempted to reconcile Romantic affirmations of feeling and

freedom with respect for historical and political fact. Many believe

that he was always more attracted to the idea of heroic struggle

itself, than to any specific goal for which the struggle was being

made. However, Carlyle’s belief in the continued use to humanity of the Hero, or Great Man,

is stated succinctly at the end of his admirably positive

aforementioned essay on Mohammed, in 1841’s ‘On Heroes, Hero Worship

& the Heroic in History’, in which he concludes that: “the Great

Man was always as lightning out of Heaven; the rest of men waited for

him like fuel, and then they too would flame.”