<Back to Index>

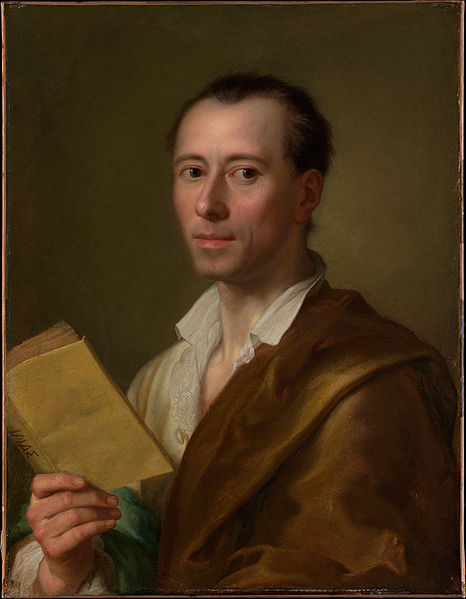

- Archaeologist and Art Historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, 1717

- Writer Joel Chandler Harris, 1845

- Prime Minister of Greece General Alexander Papagos, 1883

PAGE SPONSOR

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (December 9, 1717 – June 8, 1768), a German art historian and archaeologist, was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the difference between Greek, Greco - Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding hero of modern archaeology," Winckelmann was one of the founders of scientific archaeology and first applied the categories of style on a large, systematic basis to the history of art. Many consider him the father of the discipline of art history. His would be the decisive influence on the rise of the neoclassical movement during the late 18th century. His writings influenced not only a new science of archaeology and art history but Western painting, sculpture, literature and even philosophy. Winckelmann's History of Ancient Art (1764) was one of the first books written in German to become a classic of European literature. His subsequent influence of Lessing, Herder, Goethe, Hölderlin, Heine, Nietzsche, George, and Spengler has been provocatively called "the Tyranny of Greece over Germany."

Today, Humboldt University of Berlin's Winckelmann Institute is dedicated to the study of classical archaeology. Winckelmann was born in poverty in Stendal, Margraviate of Brandenburg.

His father, Martin Winckelmann, was a cobbler, while his mother, Anna

Maria Meyer, was the daughter of a weaver. Winckelmann's early years

were full of hardship, but his thirst for learning pushed him forward.

Later in Rome, when he was a famous scholar, he wrote: "One gets

spoiled here; but God owed me this; in my youth I suffered too much." Winckelmann attended the Coellnische Gymnasium in Berlin and the school at Salzwedel, and in 1738, at age 21, went as a student of theology to the University of Halle.

However, Winckelmann was no theologian; he had become interested in

Greek classics in his youth, but soon realized that the teachers in

Halle could not satisfy his intellectual interests in this field. He

nonetheless devoted himself privately to Greek art and literature and followed the lectures of Alexander Gottlieb Baumgarten, who coined the term "aesthetics". With the intention of becoming a physician, in 1740 Winckelmann attended medical classes at Jena.

He also taught languages. From 1743 to 1748, he was the deputy

headmaster of the gymnasium of Seehausen in the Altmark but Winckelmann

felt that work with children was not his true calling. Moreover, his

means were insufficient: his salary was so low that he had to rely on

his students' parents for free meals. He was thus obliged to accept a

tutorship near Magdeburg. While tutor for the powerful Lamprecht family, he fell into unrequited love with the handsome Lamprecht son. This was one of a series of such loves throughout his life. His enthusiasm for the male form excited Winckelmann's budding admiration of ancient Greek and Roman sculpture.

In 1748, Winckelmann wrote to

Count Heinrich von Bünau:

"... little value is set on Greek literature, to which I have devoted

myself so far as I could penetrate, when good books are so scarce and

expensive." In the same year, Winckelmann was appointed secretary of

Bünau's library at Nöthnitz, near Dresden. The library contained some 40,000 volumes. Winckelmann had read Homer, Herodotus, Sophocles, Xenophon, and Plato, but he found at Nöthnitz the works of such famous Enlightenment writers as Voltaire and Montesquieu.

To leave behind the spartan atmosphere of Prussia was a great relief

for him. Winckelmann's major duty was to assist von Bünau in

writing a book on the Holy Roman Empire and

help collect material for it. During this period he made several visits

to the collection of antiquities at Dresden, but his description of its

best paintings was left unfinished. The treasures there, nevertheless,

awakened in Winckelmann an intense interest in art, which was deepened

by his association with various artists, particularly the painter Adam Friedrich Oeser (1717 – 1799)

-- Goethe's future friend and influence — who encouraged Winckelmann in

his aesthetic studies. (Winckelmann subsequently exercised a powerful

influence over Johann Wolfgang von Goethe). In 1755, Winckelmann published his Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in Malerei und Bildhauerkunst ("Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture"), followed

by a feigned attack on the work and a defense of its principles,

ostensibly by an impartial critic. The Gedanken contains the first statement of the doctrines he afterwards developed, the ideal of "noble simplicity and quiet grandeur" (edle Einfalt und stille Größe)

and the definitive assertion, "The one way for us to become great,

perhaps inimitable, is by imitating the ancients." The work was warmly

admired not only for the ideas it contained, but for its literary

style. It made Winckelmann famous, and was reprinted several times and

soon translated into French. In England, Winckelmann's views stirred

discussion in the 1760s and 1770s, although it was limited to artistic

circles: Henry Fuseli's translation of Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks was published in 1765, but the text did not find enough readers to warrant a second edition. In

1751, the papal nuncio and Winckelmann's future employer, Alberico

Archinto, visited Nöthnitz, and in 1754 Winckelmann joined the

Roman Catholic Church. Goethe concluded that Winckelmann was a pagan,

but his conversion ultimately opened the doors of the papal library to

him. On the strength of the Gedanken über die Nachahmung der Griechischen Werke, Augustus III, king of Poland and elector of Saxony, granted him a pension of 200 thalers, so that he could continue his studies in Rome. Winckelmann arrived in Rome in November 1755. His first task there was to describe the statues in the Cortile del Belvedere — the Apollo Belvedere, the Laocoön, the so-called Antinous, and the Belvedere Torso — which represented to him the "utmost perfection of ancient sculpture." Originally, Winckelmann planned to stay in Italy only two years with the help of the grant from Dresden, but the outbreak of the Seven Years' War (1756 – 1763) changed his plans. He was named librarian to Cardinal Passionei, who was impressed by Winckelmann's beautiful Greek writing. Winckelmann also became librarian to Cardinal Archinto, and received much kindness from Cardinal Passionei. After their deaths, Winckelmann was hired as librarian in the house of Alessandro Cardinal Albani, who was forming his magnificent collection of antiquities in the villa at Porta Salaria. With the aid of his new friend, the painter Anton Raphael Mengs (1728 – 79),

with whom he first lived in Rome, Winckelmann devoted himself to the

study of Roman antiquities and gradually acquired an unrivalled

knowledge of ancient art. Winckelmann's method of careful observation

allowed him to identify Roman copies of Greek art, something that was

unusual at that time — Roman culture was considered the ultimate

achievement of Antiquity. His friend Mengs became the channel through

which Winkelmann's ideas were realized in art and spread around Europe.

("The only way for us to become great, yes, inimitable, if it is

possible, is the imitation of the Greeks," Winckelmann declared in the Gedanken.

With imitation he did not mean slavish copying: "... what is imitated,

if handled with reason, may assume another nature, as it were, and

become one's own.") Neoclassical artists attempted to revive the spirit

as well as the forms of ancient Greece and Rome. Mengs's contribution

in this was considerable — he was widely regarded as the greatest living

painter of his day. The French painter Jacques - Louis David met

Mengs in Rome (1775 – 80) and was introduced through him to the artistic

theories of Winckelmann. Earlier, while in Rome, Winckelmann met the

Scottish architect Robert Adam, whom he influenced to become a leading proponent of neoclassicism in architecture. Winckelmann's ideals were later popularized in England through the reproductions of Josiah Wedgwood's "Etruria" factory (1782). In 1760, Winckelmann's Description des pierres gravées du feu Baron de Stosch appeared, followed in 1762 by his Anmerkungen über die Baukunst der Alten ("Observations on the Architecture of the Ancients"), which included an account of the temples at Paestum. In 1758 and 1762, he visited Naples to observe the archaeological excavations being conducted at Pompeii and Herculaneum. "Despite his association with Albani, Winckelmann steered clear of the

shady world of art dealing which had compromised the scholarly

respectability of such brilliant, if much less systematic antiquarians as Francesco Ficoroni and the Baron Stosch." Winckelmann's

poverty may have played a part: the trade in antiquities was an

expensive and speculative game. In 1763, with Albani's advocacy, he was

appointed Clement XIII's Prefect of Antiquities. From

1763, while retaining his position with Albani, Winckelmann worked as a

prefect of antiquities (Prefetto delle Antichità) and scriptor

(Scriptor linguae teutonicae) of the Vatican. Winckelmann visited

Naples again, in 1765 and 1767, and wrote for the use of the electoral

prince and princess of Saxony his Briefe an Bianconi, which were published, eleven years after his death, in the Antologia romana. Winckelmann contributed various essays to the Bibliothek der schönen Wissenschaften; and, in 1766, published his Versuch einer Allegorie. Of much greater importance was the work entitled Monumenti antichi inediti ("Unpublished monuments of antiquity", 1767 – 1768), prefaced by a Trattato preliminare,

which presented a general sketch of the history of art. The plates in

this work are representations of objects which had either been falsely

explained or not explained at all. Winckelmann's explanations were of

tremendous use to the future science of archaeology, by showing through

observational method that the ultimate sources of inspiration of many

works of art supposed to be connected with Roman history were to be

found in Homer. Winckelmann's masterpiece, the Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums ("The

History of Ancient Art Among the Greeks"), published in 1764, was soon

recognized as a permanent contribution to European literature. In this

work, "Winckelmann's most significant and lasting achievement was to

produce a thorough, comprehensive and lucid chronological account of

all antique art — including that of the Egyptians and Etruscans." This

was the first work to define in the art of a civilization an organic

growth, maturity, and decline. Here, it included the revelatory tale

told by a civilization's art and artifacts — these, if we look closely,

tell us their own story of cultural factors, such as climate, freedom,

and craft. Winckelmann sets forth both the history of Greek art and of Greece.

He presents a glowing picture of the political, social, and

intellectual conditions which he believed tended to foster creative activity in ancient Greece. The

fundamental idea of Winckelmann's artistic theories are that the end of

art is beauty, and that this end can be attained only when individual

and characteristic features are strictly subordinated to an artist's

general scheme. The true artist, selecting from nature the phenomena

suited to his purpose and combining them through the exercise of his

imagination, creates an ideal type in which normal proportions are

maintained, and particular parts, such as muscles and veins, are not

permitted to break the harmony of the general outlines. In

1768 Winckelmann journeyed north over the Alps, but the Tyrol depressed

him and he decided to return to Italy. However, his friend, the

sculptor and restorer Bartolomeo Cavaceppi managed to persuade him to travel to Munich and Vienna, where he was received with honor by Maria Theresa. On his way back, he was murdered at Trieste on June 8, 1768, in a hotel bed by a fellow traveller, a man named Francesco Arcangeli,

for medals that Maria Theresa had given him. Arcangeli had thought that

he was only "un uomo di poco conto" ("a man of little account"). Winckelmann was buried in the churchyard of Trieste Cathedral.

Domenico Rosetti and Cesare Pagnini documented the last week of

Winckelmann's life; Heinrich Alexander Stoll translated the Italian

document, the so-called "Mordakte Winckelmann", into German. Winckelmann's writings are key to understanding the modern European discovery of: ancient (sometimes idealized) Greece; neoclassicism; and the doctrine of art as imitation (Nachahmung). The mimetic character of art that imitates but does not simply copy, as Winckelmann restated it, is central to any interpretation of Enlightenment classical idealism. Winckelmann stands at an early stage of the transformation of taste in the late 18th century. Winckelmann's study Sendschreiben von den Herculanischen Entdeckungen ("Letter about the Discoveries at Herculaneum") was published in 1762, and two years later Nachrichten von den neuesten Herculanischen Entdeckungen ("Report

on the Latest Discoveries at Herculaneum"). From these scholars

obtained their first real information about the excavations at Pompeii. His major work, Geschichte der Kunst des Alterthums (1764,

"The History of Ancient Art"), deeply influenced contemporary views of

the superiority of Greek art. It was translated into French in 1766 and

later into English and Italian. Among others, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing

based many of the ideas in his 'Laocoon' (1766) on Winckelmann's views

on harmony and expression in the visual arts. In

the historical portions of his writings, Winckelmann used not only the

works of art he himself had studied but the scattered notices on the

subject to be found in ancient writers; and his wide knowledge and

active imagination enabled him to offer many fruitful suggestions as to

periods about which he had little direct information. To the still

existing works of art, he applied a minute empirical scrutiny. Many of

his conclusions, based on inadequate evidence of Roman copies, would be

modified or reversed by subsequent researchers. Nonetheless, the fervid

descriptive enthusiasm of passages in his work, its strong and yet

graceful style, and its vivid descriptions of works of art gave it a

most immediate appeal. It marked an epoch by indicating the spirit in

which the study of Greek art and of ancient civilization should be

approached, and the methods by which investigators might hope to attain

solid results. To Winckelmann's contemporaries it came as a revelation,

and it exercised a profound influence on the best minds of the age. It

was read with intense interest by Lessing, who found in the earliest of Winckelmann's works the starting point for his Laocoon, and by Herder, Goethe and Kant.