<Back to Index>

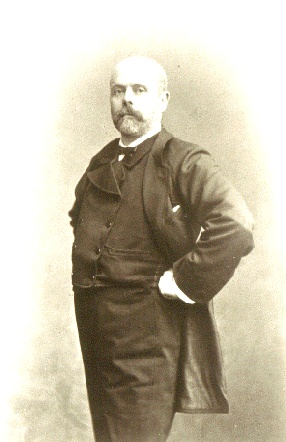

- Economist Marie Esprit Léon Walras, 1834

- Painter Antonio de la Gándara, 1861

- Lieutenant General of the Imperial Russian Army Anton Ivanovich Denikin, 1872

PAGE SPONSOR

Marie-Esprit-Léon Walras (December 16, 1834 in Évreux, Eure - January 5, 1910 in Clarens, near Montreux, Switzerland) was a French mathematical economist associated with the creation of the general equilibrium theory.

Walras was the son of French economist Auguste Walras. His father was a school administrator and not a professional economist, yet his economic thinking had a profound effect on his son. He found the value of goods by setting their scarcity relative to human wants.

Walras enrolled in the Paris School of Mines, but grew tired of engineering. He also tried careers as a bank manager, journalist, romantic novelist and a clerk at a railway company before turning to economics.

Walras also inherited his father's interest in social reform. Much like the Fabians, Walras called for the nationalization of land, believing that land’s value would always increase and that rents from that land would be sufficient to support the nation without taxes.

Another of Walras’ influences was Augustin Cournot, a former schoolmate of his father. Through Cournot, Walras came under the influence of French Rationalism and was introduced to the use of mathematics in economics.

Professor of Political Economy at the University of Lausanne, Switzerland, Walras is credited for having founded what subsequently became known, under direction of his Italian disciple, the economist and sociologist Vilfredo Pareto, as the Lausanne school of economics.

Because for a long time most of Walras' publications were only available in French, only a relatively small section of the economics profession really became familiar with his work. This changed in the 1950s, largely due to the work of William Jaffé, the translator of Walras' main works, and the editor of his Complete Correspondence (1965).

Although Walras came to be regarded as one of the three leaders of the marginalist revolution, he was not familiar with the two other leading figures of marginalism, William Stanley Jevons and Carl Menger, and developed his theories independently. In 1874 and 1877 Walras published Elements of Pure Economics, a work that led him to be considered the father of the general equilibrium theory.

The problem that Walras set out to solve was one presented by Cournot,

that even though it could be demonstrated that prices would equate

supply and demand to clear individual markets, it was unclear that an equilibrium existed for all markets simultaneously. Walras created a system of simultaneous equations in

an attempt to solve Cournot’s problem. He presented an informal

argument for the existence of an equilibrium based on the assumption

that an equilibrium exists whenever the number of equations equals the

number of unknowns. The crucial step in the argument was Walras' Law which

states that considering any particular market, if all other markets in

an economy are in equilibrium, then that specific market must also be

in equilibrium. Walras’ Law hinges on the mathematical notion that

excess market demands (or, inversely, excess market supplies) must sum

to zero. This means that, in an economy with n markets, it is

sufficient to solve n-1 simultaneous equations for market clearing.

Taking one good as the numeraire in

terms of which prices are specified, the economy has n-1 prices that

can be determined by the equation, so an equilibrium should exist. A

more rigorous version of the argument was developed by Kenneth Arrow and Gerard Debreu in the 1950s.

In 1941 Stigler wrote about Walras: There

is no general history of economic thought in English which devotes more

than passing reference to his work. … This sort of empty fame in

English speaking countries is if course attributable in large part to

Walras’ use of his mother tongue, French, and his depressing array of

mathematical formulas. What

ever caused the u-turn of Walras’ consideration in the US, the influx

of German speaking scientists – the German version of the Éléments is of 1881 – after Hitler’s rule was the initial start. To Schumpeter: Walras

is … greatest of all economists. His system of economic equilibrium,

uniting, as it does, the quality of ‘revolutionary” creativeness with

the quality of classic synthesis, is the only work by an economist that

will stand comparison with the achievements of theoretical physics.