<Back to Index>

- Physician Herman Boerhaave, 1668

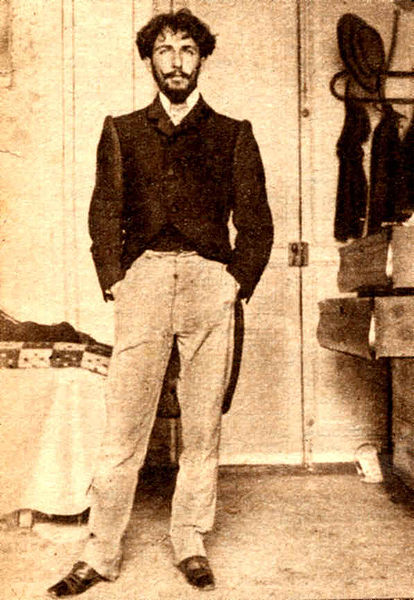

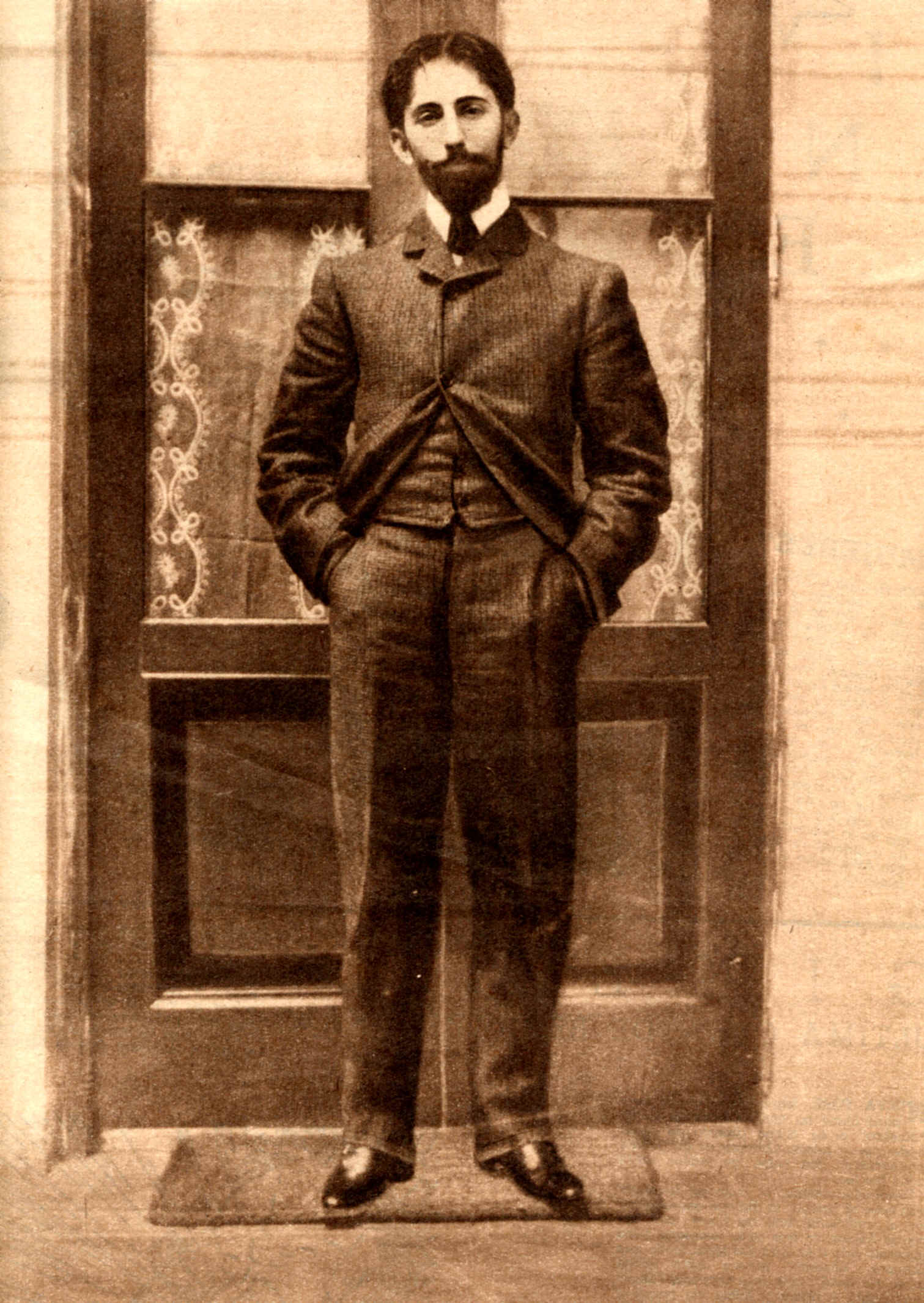

- Writer Horacio Silvestre Quiroga Forteza, 1878

- Emir of the Umayyad Caliphate Muhammad bin Qasim Al-Thaqafi, 695

PAGE SPONSOR

Horacio Silvestre Quiroga Forteza (31 December 1878 – 19 February 1937) was an Uruguayan playwright, poet, and (above all) short story writer.

He wrote stories which, in their jungle settings, use the supernatural and the bizarre to show the struggle of man and animal to survive. He also excelled in portraying mental illness and hallucinatory states. His influence can be seen in the Latin American magic realism of Gabriel García Márquez and the postmodern surrealism of Julio Cortázar. Horacio Quiroga was born in Salto, Uruguay, in 1878 as

the sixth child to a middle class family. At the time of his birth, his

father worked for eighteen years as head of the Vice - Consulate

Argentine Break. Before Quiroga was two and half months old, on March

14 of 1879 his father accidentally fired a gun he carried in his hand

and died. Quiroga was baptized just about 3 months later in the parish

of his birth town. His

national origin is not entirely clear, having many conflicting reports

about whether, besides baptism, he was registered as a citizen of

Argentina in Uruguay, or not. It

is expressed in several sources that his birth was registered in the

Consulate of Argentina which operated in that city and by the fact that his

father exercised the office of consul of that country. Quiroga finished school in Montevideo, the capital of Uruguay. He studied at the National College and

also attended the Polytechnic Institute of Montevideo for technical

training. He showed enormous interest in a variety of subjects, such as

literature, chemistry, photography, mechanics, cycling and country

life. He founded the Cycling Society of Salto and achieved the

remarkable feat of uniting the bicycle cities of Salto and Paysandu

(120 km). During

this time he worked in a repair shop and it was under the influence of

the owner's son that he became interested in philosophy. He described

the man as a, "frank and passionate soldier of materialistic

philosophy." When he was 22, Quiroga put out his poetic feelers and discovered the poetry of Leopoldo Lugones and Edgar Allan Poe and

would become a personal friend of the former. The discovery of these

authors moved him to dabble in various schools and styles: post - romanticism, Symbolism and modernism.

Armed with this background, he soon began to publish his poems in his

hometown. As he continued studying, working with publications and

Reform Magazine he improved his style and became well known. During

a carnival of 1898, the young poet met his first love, a girl named

Mary Esther Jurkovski, who would inspire two of his most important works: The Slaughter (1920) and A Season of Love.

Sadly, the misunderstandings caused by the parents of the young girl,

who disapproved of the relationship because Quiroga wasn't Jewish,

reached a crisis and the parents separated them. In his hometown he founded a magazine called Revista de Salto (1899).

Also this year, his stepfather committed suicide by shooting himself

and Quiroga found the body. With the money he received as inheritance

he went on a four month trip to Paris. The trip was a failure and he

came back sad and discouraged. Upon

returning to his country, Quiroga gathered his friends Federico

Ferrando, Alberto Brignole, July Jaureche, Fernandez Saldaña,

Jose Hasd and Asdrubal Delgado, and with them founded the "Consistory

of the Gay Saber" (The Consistency of Poetic Knowledge), a literary

laboratory for their experimental writing where they found new ways to

express themselves and their modernist goals. In 1901, Quiroga published his first book, Coral Reefs, but this achievement was overshadowed by the deaths of his two brothers, Prudencio and Pastora, who were victims of Typhoid fever in

Chaco. The fateful year of 1901 still held another horrible surprise

for the writer: his friend Federico Ferrando, had received bad reviews

from Germain Papini, a Montevideo journalist, and challenged him to a

duel. Quiroga, worried about the safety of Ferrando, offered to check

and clean the gun that was to be used. Unexpectedly, while inspecting

the weapon, he accidentally fired off a shot that hit Ferrando in the

mouth, killing him instantly. When the police arrived, Quiroga was

arrested, interrogated and transferred to a correctional prison. The

police investigated the unfortunate circumstances of the homicide and

deemed the incident accidental, releasing Quiroga after four days of

detention. He was eventually exonerated. Wracked

with grief and guilt over the death of his beloved friend, Quiroga

dissolved "The Consistory" and moved from Uruguay to Argentina. He

crossed the Rio de la Plata in 1902 and went to live with Mary, one of

his sisters. In Buenos Aires, the artist reached professional maturity,

which would reach its climax during his stays in the jungle. In

addition, his sister introduced him to pedagogy, and found him work as

a teacher under contract on the board of examination for the Colegio Nacional de Buenos Aires. He was appointed professor of Castilian in the British School of Buenos Aires in March 1903. In

June of that year, Quiroga, already an experienced photographer, would

follow Leopoldo Lugones on an expedition, funded by the Ministry of

Education, in which the famous Argentine poet planned to investigate

some ruins of Jesuit missions in the province. The jungle missionary

left a profound impression on Quiroga that marked his life forever: he

spent six months and the last of his inheritance (seven thousand pesos)

on some land for cotton in Chaco, located seven kilometers from

Resistance, next to the Saladito River. The project failed, due to

problems with his aboriginal workers, but Quiroga's life was enriched

by experiencing life as a country man for the first time. His narrative

benefited from his new knowledge of country people and rural culture; this permanently changed his style. Upon

returning to Buenos Aires after his failed experience in the Chaco,

Quiroga embraced the short story with passion and energy. In 1904 he

published a book of stories called The Crime of Another , which was heavily influenced by the style of Edgar Allan Poe.

Quiroga did not mind these early comparisons with Poe, and until the

end of his life he would often say that Poe was his first and principle

teacher. Quiroga

worked for the next two years on a multitude of stories, many were

about rural terror, but others were delightful stories for children.

During this time he wrote the magnificent horror story, "The Feather

Pillow". It was published in 1907 by a famous magazine in Argentina, Faces and Masks,

which went on to publish eight of his other stories that year. Shortly

after it was published, Quiroga became famous and his writings were

eagerly sought by thousands of readers. In

1906 Quiroga decided to return to his beloved jungle. Taking advantage

of the fact that the government wanted the land to be used, Quiroga

bought a farm (with Vincent Gozalbo) of 185 hectares in the province of Misiones, on the banks of the Upper Parana, and began making preparations, while teaching Castilian and Literature

nearby. He moved in during the winter of 1908 building the bungalow

where he would live. Quiroga fell in love with one of his teenage students, Ana Maria Cires, to whom he would dedicate his first novel, entitled, History of a Troubled Love.

Quiroga insisted on the relationship despite the opposition of her

parents, eventually garnering their permission to marry her and take

her to live in the jungle with him. Quiroga's parents - in - law were

concerned about the risks of living in Misiones, a wild region, and

that is why they decided to join their daughter and son - in - law, and

live close by in order to help them. So, Ana Maria's parents and a

friend of her mother, moved into a house near Quiroga. In

1911 Ana Maria gave birth to the couple's first child, at their home in

the jungle; they named her Egle Quiroga. During the same year the

writer began farming in partnership with his friend, fellow Uruguayan,

Vicente Gozalbo, and was also appointed Justice of the Peace in the Civil Registry of San Ignacio.

This job was not the best fit for Quiroga who, forgetful, disorganized

and careless, took to the habit of jotting down deaths, marriages and

births on small pieces of paper and "archived" them in a cookie tin.

Later, a character of one of his stories was given a similar trait. The

following year Ana Maria gave birth to a son, named Darius. Quiroga

decided, just as the children were learning to walk, that he would

personally take care of their education. Stern and dictatorial, Quiroga

demanded that every little detail was done according to his

requirements. From a young age, his children got used to the mountains

and jungle. Quiroga exposed them to danger (risk - free danger) so that

they would be able to cope alone and overcome any situation. He even

went as far as to leave them alone one night in the jungle, or another

time made them sit on the edge of a cliff with their legs dangling in

the void. The daughter learned to breed wild animals and the son to use

the shotgun, ride a bike and sail alone in a canoe. Quiroga's children

never refused to be part of these experiences and, actually, enjoyed

them. Their mother, however, was terrified and exasperated. Between

1912 and 1915 the writer, who already had experience as a cotton farmer

and herbalist, undertook a bold pursuit to increase the farming and

maximize the natural resources of their lands. He began to distill

oranges, produce coal and resins, as well as, many other similar

activities. Meanwhile, he raised livestock, domesticated wild animals,

hunted and fished. Literature continued to be the peak of his life: in

the journal Fray Mocho de Buenos Aires Quiroga published numerous stories, many set in the jungle and populated by characters so naturalistic that they seemed real. But

Quiroga's wife was not happy: she failed to adapt to jungle life and

asked her husband, again and again, to return to Buenos Aires or, if he

wanted to stay, to let her return alone. When Quiroga refused both

possibilities she became immersed in a serious depression. So Ana Maria

would become a new tragedy in Quiroga's life when she committed suicide

by consuming mercury poisoning in 1915 after a violent fight with the

writer. She suffered in terrible agony for eight days, dying in

horrible pain and leaving Quiroga and children plunged into the darkest

despair. After this tragedy, Quiroga quickly left for Buenos Aires with

his children where he became an Under - Secretary General Accountant in

the Uruguayan Consulat, with the efforts of some of his friends who

wanted to help. Throughout the year 1917 Quiroga lived in a basement

with his children on Avenue Canning, alternating his diplomatic work

with setting up a home office and working on many stories, which were

being published in prestigious magazines. Quiroga collected most of the

stories in several books, the first was Tales of Love, Madness and Death (1917).

Manuel Galvez, owner of a publishing firm, had suggested that he write

it and the volume immediately became a huge success with audiences and

critics, consolidating Quiroga as the true master of the Latin American

short story. The following year he settled in a small apartment on Calle Agüero, while he published Jungle Tales (1918,

a collection of children's stories featuring animals and set in the

Misiones rainforest). Quiroga dedicated this book to his children, who

accompanied him during that rough period of poverty in the damp

basement. 1919

was a good year for Quiroga, with two major promotions in the consular

ranks and the publication of his new book of stories, The Wild.

The next year, following the idea of "The Consistory", Quiroga founded

the Anaconda Association, a group of intellectuals involved in cultural

activities in Argentina and Uruguay. His only play, The Slaughtered, was published in 1920 and was released in 1921, when Anaconda was

released (another book of short stories). An important Argentine

newspaper, La Nation, also began to publish his stories, which by now

already enjoyed impressive popularity. Between 1922 and 1924, Quiroga

served as secretary of a cultural embassy to Brazil and he published

his new book: The Desert (stories). For

a while the writer was devoted to film criticism, taking charge of the

magazine section of "Atlantis, The Home and The Nation". He also wrote

the screenplay for a feature film (The Florida Raft) that was

never filmed. Shortly thereafter, was invited to form a School of

Cinematography, by Russian investors, but it was unsuccessful. Soon

after, Quiroga returned to Misiones. He was in love again, this time

with a 22 year old Ana Maria Palacio. He tried to persuade her parents

to let her go to live in the jungle with him. The constant refusal of

the parents and the consequent failure of love inspired the theme of

his second novel, Past love (published

later, in 1929). The novel contains autobiographical elements of the

strategies he used himself to get the girl, like, leaving messages in a

hollowed branch, sending letters written in code and trying to dig a

long tunnel to her room with thoughts of kidnap. Finally the parents

grew tired of Quiroga's attempts and took her away so he was forced to

renounce his love. In the workshop in his home where he would build a boat baptized Gaviota.

His home was on the water and he used the boat to go from San Ignacio

downriver to Buenos Aires and on numerous river expeditions. In

early 1926 Quiroga returned to Buenos Aires and rented a villa in a

suburban area. At the very apex of his popularity, a major publisher

honored him, along with other literary figures of the time such as

Arturo Capdevila, Baldomero Fernandez Moreno, Benito Lynch, Joan of

Ibarbourou, Armando Donoso and Luis Franco. A

lover of classical music, Quiroga came often to the concerts of the

Wagner Association. He also tirelessly read technical texts, manuals on

mechanics, and books on arts and physics. In 1927, Quiroga had decided to raise and domesticate wild animals, while publishing his new book of short stories, Exiles.

But the amorous artist had already set his eyes on what would be his

last and final love: Maria Elena Bravo, a classmate of his daughter

Egle, who married him that year, not even 20 years old (He was 49). In

1932 Quiroga last settled in Misiones, where he would retire, with his

wife and third daughter (Maria Elena, called Pitoca, who was born in

1928). To do this, he got a decree transferring his consular office to

a nearby city. He was devoted to living quietly in the jungle with his

wife and daughter. But

due to a change of government, his services were declined and he was

expelled from the consulate. To exacerbate Quiroga's problems, his wife

did not like living in the jungle, so fighting and violent discussions

became a daily activity. In this time of frustration and pain he published a collection of short stories titled Beyond (1935). From his interest in the work of Munthe and Ibsen, Quiroga began reading new authors and styles, and began planning his autobiography. In 1935 Quiroga began to experience uncomfortable symptoms, apparently related to prostatitis or

other prostate disease. With intensifying the pain and difficulty

urinating, his wife managed to convince him to go to Posadas, where he

was diagnosed with prostate hypertrophy. But

the problems continued for the Quiroga family: his wife and daughter

left him permanently, leaving him alone and sick in the jungle. They

went back to Buenos Aires, and the writer's spirits fell completely in

the face of this serious loss. When

he could not stand the disease anymore, Quiroga traveled to Buenos

Aires for treatment. In 1937, an exploratory surgery revealed that he

suffered from an advanced case of prostate cancer, untreatable and

inoperable. Maria Elena and his large group of friends came to comfort

him. When

Quiroga was in the Emergency Ward, he had learned that a patient was

shut up in the basement with hideous deformities similar to those of

the infamous English Joseph Merrick (the "Elephant Man").

Taking pity, Quiroga demanded that the patient, named Vicent

Batistessa, be released from confinement and moved into his room. As

expected, Batistessa befriended and paid eternal gratitude to the great

storyteller. Feeling

desperate about his present suffering and realizing that his life was

over, he told Batistessa his plan to shorten his suffering and

Batistessa promised to help. That morning (February 19, 1937) in the

presence of his friend, Horacio Quiroga drank a glass of cyanide that killed him within minutes from unbearable pains. His

body was buried in the Casa del Teatro de la Sociedad Argentina de

Escritores (SADE), of which he was the founder and vice president, though, his remains were later repatriated to his homeland. Follower of the modernist school founded by Ruben Dario and being an obsessive reader of Edgar Allan Poe and Guy de Maupassant, Quiroga was attracted to topics covering the most intriguing aspects of

nature, often tinged with horror, disease, and suffering for human

beings. Many of his stories belong to this movement, embodied in his

work Tales of Love, Madness and Death. Quiroga was also influenced by British writer Rudyard Kipling (The Jungle Book), which is shown in his own Jungle Tales, a delightful exercise in fantasy divided into several stories featuring animals. His Ten Rules for the Perfect Storyteller,

dedicated to young writers, provides certain contradictions in his own

work. While the Decalogue touts economic and precise style, using few

adjectives, natural and simple wording, and clarity of expression, in

many of his own stories Quiroga did not follow his own precepts, using

ornate language, with plenty of adjectives and at times ostentatious vocabulary. As

he further developed his particular style, Quiroga evolved into

realistic portraits (often anguished and desperate) of the wild nature

around him in Misiones: the jungle, the river, wildlife, climate, and

terrain make up the scaffolding and scenery in which his characters

move, suffer, and often die. Especially in his stories, Quiroga

describes the tragedy that haunts the miserable rural workers in the

region, the dangers and sufferings to which they are exposed, and how

this existential pain is perpetuated to succeeding generations. He also

experimented with many subjects considered taboo in the society of

early twentieth century. Some scholars find parallels between Quiroga's apparent fascination with death, accidents, and illness (comparable to Edgar Allan Poe and Baudelaire) and his incredibly tragic life. In his first book, Coral Reefs,

consisting of 18 poems, 30 pages of poetic prose, and four stories,

Quiroga shows his immaturity and adolescent confusion. On the other

hand, he shows a glimpse of the modernist style and naturalistic

elements that would come to characterize his later work. His two novels: History of a Troubled Love and Past Love deal

with the same theme that haunted the author in his personal life: love

affairs between older men and teenage girls. In the first novel Quiroga

divided the action into three parts. In the first, a 9 year old girl

falls in love with an older man. In the second part, it is eight years

later and the man, who had noticed her affection, begins to woo her.

The third part is the present tense of the novel, in which it has been

ten years since the young girl left the man. In Past Love history

repeats itself: a grown man returns to a place after years of absence,

and falls for a young woman he had loved as a child. Knowing

the personal history of Quiroga, the two novels feature some

autobiographical components. For example, the protagonist in History of a Trouble Love is

named Egle (the name of Quiroga's daughter, whose classmate he later

married). Also, in these novels there is a great deal of emphasis on

the opposition of the girls' parents, rejection that Quiroga had

accepted as part of his life and that he always had to deal with. The critics never liked his novels and called his only play The Slaughtered "a

mistake." They considered his short stories to be his most transcendent

works, and some have credited them with stimulaing all Latin American

short stories after him. This makes sense as Quiroga was the first to

be concerned about the technical aspects of the short story, tirelessly

honing his style (for which he always returns to the same subjects) to

reach near perfection in his last works. Though

clearly influenced by modernism, he gradually begins to turn the

decadent Uruguayan language, to describing the natural surroundings

with meticulous precision. But he makes it clear that Nature's

relationship with man is always one of conflict. Loss, injury, misery,

failures, starvation, death, and animal attacks plague Quiroga's human

characters. Nature is hostile, and almost always wins. Quiroga's

morbid obsession with torment and death is much more easily accepted by

the characters than by the reader: in the narrative technique the

author uses, he presents players accustomed to risk and danger, playing

by clear and specific rules. They know not to make mistakes because the

forest is unforgiving, and failure often means death. Nature is blind

but fair, and the attacks on the farmer or fisherman (a swarm of angry

bees, an alligator, a bloodsucking parasite, etc.) are simply obstacles

in a horrible game in which the Man tries to snatch property or natural

resources (reflecting Quiroga's efforts in life) and Nature

absolutely refuses to let go; an unequal struggle that usually ends

with the human loss, dementia, death, or simply disappointment. Sensitive,

excitable, given to impossible love, thwarted in his commercial

enterprises but still highly creative, Quiroga waded through his tragic

life and suffered through nature to construct, with the eyes of a

careful observer, narrative work which critics considered

"autobiographical poetry". Perhaps it is this "internal realism" or the

"organic" nature of his writing that created the irresistible draw that

Quiroga continues to have on readers.