<Back to Index>

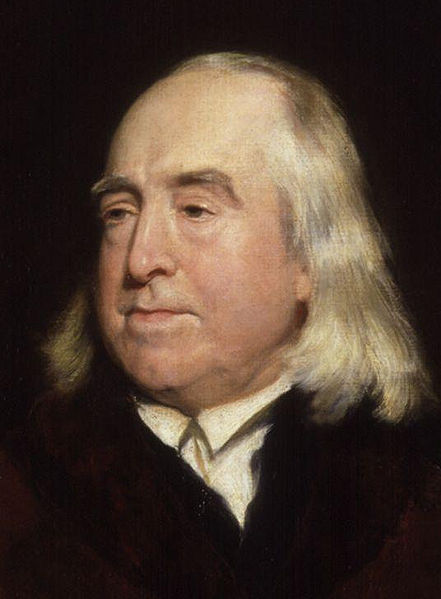

- Philosopher Jeremy Bentham, 1748

- Painter Charles François Daubigny, 1817

- 7th President of Argentina Domingo Faustino Sarmiento, 1811

PAGE SPONSOR

Jeremy Bentham (15 February 1748 – 6 June 1832) was an English jurist, philosopher, and legal and social reformer. He became a leading theorist in Anglo - American philosophy of law and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He is best known for his advocacy of utilitarianism and the ethical treatment of animals, and the idea of the panopticon.

His position included arguments in favour of individual and economic freedom, usury, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and the decriminalising of homosexual acts. He

argued for the abolition of slavery and the death penalty and for the

abolition of physical punishment, including that of children. Although strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights, calling them "nonsense upon stilts." He

became the most influential of the utilitarians, through his own work

and that of his students. These included his secretary and collaborator

on the utilitarian school of philosophy, James Mill; James Mill's son John Stuart Mill; John Austin, legal philosopher; and several political leaders, including Robert Owen, a founder of modern socialism. He is considered the godfather of University College London (UCL).

Bentham was born in Spitalfields, London, into a wealthy Tory family. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study Latin at the age of three. He attended Westminster School and, in 1760, at age 12, was sent by his father to The Queen's College, Oxford, where he took his Bachelor's degree in 1763 and his Master's degree in 1766. He trained as a lawyer and, though he never practised, was called to the bar in 1769. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of the English legal code, which he termed the "Demon of Chikane".

When the American colonies published their Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the British government did not issue any official response but instead secretly commissioned London lawyer and pamphleteer John Lind to publish a rebuttal. His 130 page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled "Short Review of the Declaration" authored by Bentham, a friend of Lind's, which attacked and mocked the Americans' political philosophy.

Among his many proposals for legal and social reform was a design for a prison building he called the Panopticon. Although it was never built, the idea had an important influence upon later generations of thinkers. Twentieth century French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the Panopticon was paradigmatic of a whole raft of 19th century 'disciplinary' institutions. It is said that Mexican prison "Lecumberri" was designed on the basis of this idea.

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. Adam Smith, for example, opposed free interest rates before he was made aware of Bentham's arguments on the subject. As a result of his correspondence with Mirabeau and other leaders of the French Revolution, he was declared an honorary citizen of France. Bentham was an outspoken critic of the revolutionary discourse of natural rights and of the violence that arose after the Jacobins took power (1792). Between 1808 and 1810, he held a personal friendship with Latin American Independence Precursor Francisco de Miranda and paid visits to Miranda's Grafton Way house in London.

In 1823, he co-founded the Westminster Review with James Mill as a journal for the "Philosophical Radicals" – a group of younger disciples through whom Bentham exerted considerable influence in British public life.

Bentham is frequently associated with the foundation of the University of London, specifically University College London (UCL), though he was 78 years old when UCL opened in 1826 and played no active part in its establishment. It is likely that without his inspiration, UCL would not have been created when it was. Bentham strongly believed that education should be more widely available, particularly to those who were not wealthy or who did not belong to the established church, both of which were required of students by Oxford and Cambridge. As UCL was the first English university to admit all, regardless of race, creed or political belief, it was largely consistent with Bentham's vision. He oversaw the appointment of one of his pupils, John Austin, as the first professor of Jurisprudence in 1829. An insight into his character is given in Michael St. John Packe's, The Life of John Stuart Mill:

| “ | During his youthful visits to Bowood House, the country seat of his patron Lord Lansdowne, he had passed his time at falling unsuccessfully in love with all the ladies of the house, whom he courted with a clumsy jocularity, while playing chess with them or giving them lessons on the harpsichord. Hopeful to the last, at the age of eighty he wrote again to one of them, recalling to her memory the far-off days when she had 'presented him, in ceremony, with the flower in the green lane' [citing Bentham's memoirs]. To the end of his life he could not hear of Bowood without tears swimming in his eyes, and he was forced to exclaim, 'Take me forward, I entreat you, to the future – do not let me go back to the past.' | ” |

John Bowring, a British politician who had been Bentham's trusted friend, was appointed his literary executor and charged with the task of preparing a collected edition of his works. This appeared in 11 volumes in 1838 - 1843: Bowring based his edition on previously published editions (including those of Dumont) rather than Bentham's own manuscripts, and he did not reprint Bentham's works on religion at all. Bowring's work has been criticised, although it includes such interesting writings on international relations as Bentham's A Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace written 1786 - 89, which forms part IV of the Principles of International Law.

In 1952 - 54, Werner Stark published a three volume set, Jeremy Bentham's Economic Writings,

in which he attempted to bring together all of Bentham's writings on

economic matters, including both published and unpublished material.

Not trusting Bowring's edition, he painstakingly reviewed thousands of

Bentham's original manuscripts and notes, a task made monumentally more

difficult because of the manner in which they had been left by Bentham

and organised by Bowring.

Bentham's ambition in life was to create a "Pannomion", a complete utilitarian code of law. Bentham not only proposed many legal and social reforms, but also expounded an underlying moral principle on which they should be based. This utilitarianism philosophy argued that the right act or policy was that which would cause "the greatest good for the greatest number of people", also known as "the greatest happiness principle", or the principle of utility. He wrote inThe Principles of Morals and Legislation:

| “ | Nature has placed mankind under the governance of two sovereign masters, pain and pleasure. It is for them alone to point out what we ought to do, as well as to determine what we shall do. On the one hand the standard of right and wrong, on the other the chain of causes and effects, are fastened to their throne. They govern us in all we do, in all we say, in all we think... | ” |

He also suggested a procedure for estimating the moral status of any action, which he called the Hedonistic or felicific calculus. Utilitarianism was revised and expanded by Bentham's student John Stuart Mill. In Mill's hands, "Benthamism" became a major element in the liberal conception of state policy objectives.

Bentham proposed a classification of 12 pains and 14 pleasures and 'felicific calculus' by which we might test the 'happiness factor' of any action. Nonetheless, it should not be overlooked that Bentham's 'hedonistic' theory (a term from J.J.C. Smart), unlike Mill's, is often said to lack a principle of fairness embodied in a conception of justice. In "Bentham and the Common Law Tradition", Gerald J. Postema states, "No moral concept suffers more at Bentham's hand than the concept of justice. There is no sustained, mature analysis of the notion ..." Thus, some critics object, it would be acceptable to torture one person if this would produce an amount of happiness in other people outweighing the unhappiness of the tortured individual. However, as P.J. Kelly argued in his book, Utilitarianism and Distributive Justice: Jeremy Bentham and the Civil Law, Bentham had a theory of justice that prevented such consequences. According to Kelly, for Bentham the law "provides the basic framework of social interaction by delimiting spheres of personal inviolability within which individuals can form and pursue their own conceptions of well-being." It provides security, a precondition for the formation of expectations. As the hedonic calculus shows "expectation utilities" to be much higher than natural ones, it follows that Bentham does not favour the sacrifice of a few to the benefit of the many.

Bentham's Principles of Legislation focuses

on the principle of utility and how this view of morality ties into

legislative practices. His principle of utility regards "good" as that

which produces the greatest amount of pleasure and the minimum amount

of pain and "evil" as that which produces the most pain without the

pleasure. This concept of pleasure and pain is defined by Bentham as

physical as well as spiritual. Bentham writes about this principle as

it manifests itself within the legislation of a society. He lays down a

set of criteria for measuring the extent of pain or pleasure that a

certain decision will create. The

criteria are divided into the categories of intensity, duration,

certainty, proximity, productiveness, purity, and extent. Using these

measurements, he reviews the concept of punishment and when it should

be used as far as whether a punishment will create more pleasure or

more pain for a society. He calls for legislators to determine whether

punishment creates an even more evil offense. Instead of suppressing

the evil acts, Bentham is arguing that certain unnecessary laws and

punishments could ultimately lead to new and more dangerous vices than

those being punished to begin with. Bentham follows these statements

with explanations on how antiquity, religion, reproach of innovation,

metaphor, fiction, fancy, antipathy and sympathy, begging the question

and imaginary law are not justification for the creation of

legislature. Instead, Bentham is calling upon legislators to measure

the pleasures and pains associated with any legislation and to form

laws in order to create the greatest good for the greatest number. He

argues that the concept of the individual pursuing his or her own

happiness cannot be necessarily declared "right", because often these

individual pursuits can lead to greater pain and less pleasure for the

society as a whole. Therefore, the legislation of a society is vital to

maintaining a society with optimum pleasure and the minimum degree of

pain for the greatest amount of people.

His opinions about monetary economics were completely different from those of David Ricardo; however, they had some similarities to those of Thornton.

He focused on monetary expansion as a means of helping to create full

employment. He was also aware of the relevance of forced saving,

propensity to consume, the saving - investment relationship, and other

matters that form the content of modern income and employment analysis.

His monetary view was close to the fundamental concepts employed in his

model of utilitarian decision making. His work is widely regarded to be

at the forefront of modern welfare economics. Bentham

stated that pleasures and pains can be ranked according to their value

or "dimension" such as intensity, duration, certainty of a pleasure or

a pain. He was concerned with maxima and minima of pleasures and pains;

and they set a precedent for the future employment of the maximisation

principle in the economics of the consumer, the firm and the search for

an optimum in welfare economics.

Bentham is widely recognised as one of the earliest proponents of animal rights. He argued that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, should be the benchmark, or what he called the "insuperable line." If reason alone were the criterion by which we judge who ought to have rights, human infants and adults with certain forms of disability might fall short, too. In 1789, alluding to the limited degree of legal protection afforded to slaves in the French West Indies by the Code Noir, he wrote:

| “ | The day has been, I am sad to say in many places it is not yet past, in which the greater part of the species, under the denomination of slaves, have been treated by the law exactly upon the same footing, as, in England for example, the inferior races of animals are still. The day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been witholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason a human being should be abandoned without redress to the caprice of a tormentor. It may one day come to be recognised that the number of the legs, the villosity of the skin, or the termination of the os sacrum are reasons equally insufficient for abandoning a sensitive being to the same fate. What else is it that should trace the insuperable line? Is it the faculty of reason or perhaps the faculty of discourse? But a full-grown horse or dog, is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as a more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month, old. But suppose the case were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor, Can they talk? but, Can they suffer? | ” |

As requested in his will, Bentham's body was dissected as part of a public anatomy lecture. Afterward, the skeleton and head were preserved and stored in a wooden cabinet called the "Auto-icon", with the skeleton stuffed out with hay and dressed in Bentham's clothes. Originally kept by his disciple Thomas Southwood Smith, it was acquired by University College London in 1850. It is normally kept on public display at the end of the South Cloisters in the main building of the college, but for the 100th and 150th anniversaries of the college, it was brought to the meeting of the College Council, where it was listed as "present but not voting". The Auto-icon has a wax head, as Bentham's head was badly damaged in the preservation process. The real head was displayed in the same case for many years but became the target of repeated student pranks, including being stolen on more than one occasion. It is now locked away securely.

The Bentham Project in UCL has launched a digitisation and crowdsourcing initiative whose aim is to engage the public in the online transcription of Bentham's unstudied manuscripts. Manuscripts can be viewed and transcribed by signing-up for an MediaWiki account in Transcription Desk via the Transcribe Bentham website.