<Back to Index>

- Microbiologist René Jules Dubos, 1901

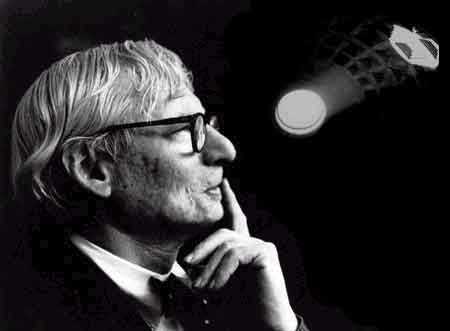

- Architect Louis Isadore Kahn (Itze Leib Schmuilowsky), 1901

- Chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin, 1904

PAGE SPONSOR

Louis Isadore Kahn (born Itze-Leib Schmuilowsky) (February 20, 1901 or 1902 – March 17, 1974) was a world renowned American architect of Estonian Jewish origin, based in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. After working in various capacities for several firms in Philadelphia, he founded his own atelier in 1935. While continuing his private practice, he served as a design critic and professor of architecture at Yale School of Architecture from 1947 to 1957. From 1957 until his death, he was a professor of architecture at the School of Design at the University of Pennsylvania. Influenced by ancient ruins, Kahn's style tends to the monumental and monolithic; his heavy buildings do not hide their weight, their materials, or the way they are assembled.

Louis Kahn, whose original name was Itze-Leib (Leiser-Itze) Schmuilowsky (Schmalowski), was born into a poor Jewish family in Pärnu and spent the rest of his early childhood in Kuressaare on the Estonian island of Saaremaa, then part of the Russian Empire. At age 3, he saw coals in the stove and was captivated by the light of

the coal. He put the coal in an apron which later seared his face; he carried these scars for the rest of his life. In 1906, his family immigrated to the United States, fearing that his father would be recalled into the military during the Russo - Japanese War.

His actual birth year may have been inaccurately recorded in the

process of immigration. According to his son's documentary film in 2003 the

family couldn't afford pencils but made their own charcoal sticks from

burnt twigs so that Louis could earn a little money from drawings and

later by playing piano to accompany silent movies. He became a naturalized citizen on May 15, 1914. His father changed their name in 1915. He trained in a rigorous Beaux-Arts tradition, with its emphasis on drawing, at the University of Pennsylvania. After completing his Bachelor of Architecture in 1924, Kahn worked as senior draftsman in the office of City Architect John Molitor. In this capacity, he worked on the design for the 1926 Sesquicentennial Exposition. In 1928, Kahn made a European tour and took a particular interest in the medieval walled city of Carcassonne, France, and the castles of Scotland rather than any of the strongholds of classicism or modernism. After returning to the States in 1929, Kahn worked in the offices of Paul Philippe Cret, his former studio critic at the University of Pennsylvania, and in the offices of Zantzinger, Borie and Medary in Philadelphia. In 1932, Kahn and Dominique Berninger founded the Architectural Research Group, whose members were interested in the populist social agenda and new aesthetics of the European avant-gardes.

Among the projects Kahn worked on during this collaboration are unbuilt

schemes for public housing that had originally been presented to the Public Works Administration. Among the more important of Kahn's early collaborations was with George Howe. Kahn worked with Howe in late 1930s on projects for the Philadelphia Housing Authority and again in 1940, along with German born architect Oscar Stonorov for the design of housing developments in other parts of Pennsylvania. Kahn

did not find his distinctive architectural style until he was in his

fifties. Initially working in a fairly orthodox version of the

International Style, a stay at the American Academy in Rome in

the early 1950s marked a turning point in Kahn's career. The

back-to-the-basics approach he adopted after visiting the ruins of

ancient buildings in Italy, Greece, and Egypt helped him to develop his

own style of architecture influenced by earlier modern movements but

not limited by their sometimes dogmatic ideologies. In 1961 he received a grant from the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts to study traffic movement in Philadelphia and create a proposal for a viaduct system. He describes this proposal at a lecture given in 1962 at the International Design Conference in Aspen, Colorado: In

the center of town the streets should become buildings. This should be

interplayed with a sense of movement which does not tax local streets

for non-local traffic. There should be a system of viaducts which

encase an area which can reclaim the local streets for their own use,

and it should be made so this viaduct has a ground floor of shops and

usable area. A model which I did for the Graham Foundation recently,

and which I presented to Mr. Entenza, showed the scheme. Kahn's teaching career began at Yale University in 1947, and he was eventually named Albert F. Bemis Professor of Architecture and Planning at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1962 and Paul Philippe Cret Professor of Architecture at the University of Pennsylvania in 1966 and was also a Visiting Lecturer at Princeton University from 1961 to 1967. Kahn was elected a Fellow in the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1953. He was made a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1964. He was awarded the Frank P. Brown Medal in 1964. He was made a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1968 and awarded the AIA Gold Medal, the highest award given by the AIA, in 1971 and the Royal Gold Medal by the RIBA in 1972.

In 1974, Kahn died of a heart attack in a men's restroom in Pennsylvania Station in New York. He

went unidentified for three days because he had crossed out the home

address on his passport. He had just returned from a work trip to Bangladesh, and despite his long career, he was deeply in debt when he died.

Kahn had three different families with three different women: his wife, Esther, whom he married in 1930; Anne Tyng, who began her working collaboration and personal relationship with Kahn in 1945; and Harriet Pattison. His obituary in the New York Times, written by Paul Goldberger, mentions only Esther and his daughter by her as survivors. But in 2003, Kahn's son with Pattison, Nathaniel Kahn, released an Oscar nominated biographical documentary about his father, titled My Architect: A Son's Journey,

which gives glimpses of the architecture while focusing on talking to

the people who knew him: family, friends, and colleagues. It includes interviews with renowned architect contemporaries such as B.V. Doshi, Frank Gehry, Ed Bacon, Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, and Robert A.M. Stern,

but also an insider's view of Kahn's unusual family arrangements. The

unusual manner of his death is used as a point of departure and a

metaphor for Kahn's "nomadic" life in the film. Louis Kahn's work infused the International style with a fastidious, highly personal taste, a poetry of light. His few projects reflect his deep personal involvement with each. Isamu Noguchi called

him "a philosopher among architects." He was known for his ability to

create monumental architecture that responded to the human scale. He

was also concerned with creating strong formal distinctions between served spaces and servant spaces. What he meant by servant spaces

was not spaces for servants, but rather spaces that serve other spaces,

such as stairwells, corridors, restrooms, or any other back-of-house

function like storage space or mechanical rooms. His palette of

materials tended toward heavily textured brick and bare concrete, the

textures often reinforced by juxtaposition to highly refined surfaces

such as travertine marble. While

widely known for his spaces' poetic sensibilities, Kahn also worked

closely with engineers and contractors on his buildings. The results

were often technically innovative and highly refined. In addition to

the influence Kahn's more well known work has on contemporary

architects (such as Mazharul Islam, Tadao Ando), some of his work (especially the unbuilt City Tower Project) became very influential among the high-tech architects of the late 20th century (such as Renzo Piano, who worked in Kahn's office, Richard Rogers and Norman Foster). His prominent apprentices include Mazharul Islam, Moshe Safdie, Robert Venturi, Jack Diamond. Many years after his death, Kahn continues to inspire controversy. Interest is growing in a plan to build a Kahn designed Franklin D. Roosevelt Four Freedoms Park at the southern tip of Roosevelt Island. A New York Times editorial opined: There's

a magic to the project. That the task is daunting makes it worthy of

the man it honors, who guided the nation through the Depression, the

New Deal and a world war. As for Mr. Kahn, he died in 1974, as he

passed alone through New York's Penn Station. In his briefcase were

renderings of the memorial, his last completed plan. The editorial describes Kahn's plan as: ...simple

and elegant. Drawing inspiration from Roosevelt's defense of the Four

Freedoms – of speech and religion, and from want and fear – he designed

an open 'room and a garden' at the bottom of the island. Trees on

either side form a 'V' defining a green space, and leading to a

two-walled stone room at the water's edge that frames the United

Nations and the rest of the skyline. Critics note that the panoramic view of Manhattan and the UN are actually blocked by the walls of that room and by the trees. Other as-yet-unanswered critics have argued more broadly that not enough

thought has been given to what visitors to the memorial would actually

be able to do at the site. The proposed project is opposed by a majority of island residents who were surveyed by the Trust for Public Land, a national land conservation group currently working extensively on the island. The

movement for the memorial, which was conceived by Kahn's firm almost 35

years ago, needed to raise $40 million by the end of 2007; as of July

20, it had collected $5.1 million. There is a merest hint in Architectural Record about the often-heard argument that it must be built because it was literally Kahn's last project; and

this is rebutted by those who've said the plans aren't enough like

Kahn's other work for it to be touted as a memorial to Kahn as well as

FDR.