<Back to Index>

- Microbiologist René Jules Dubos, 1901

- Architect Louis Isadore Kahn (Itze Leib Schmuilowsky), 1901

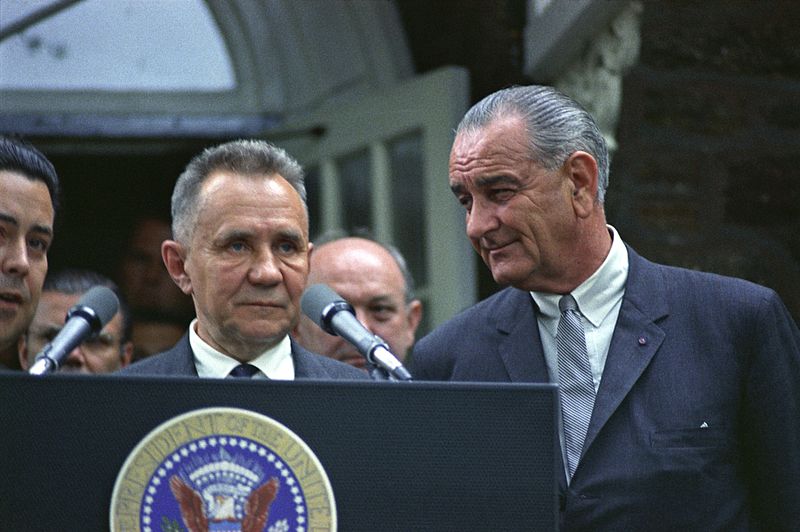

- Chairman of the Council of Ministers Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin, 1904

PAGE SPONSOR

Alexei Nikolayevich Kosygin (Russian: Алексе́й Никола́евич Косы́гин, Aleksej Nikolajevič Kosygin; 20 February 1904 – 18 December 1980) was a Soviet Russian statesman from the start to the end of the Cold War. He served as Chairman of the Council of Ministers from 1964 to 1980, and as Chairman of the Council of Peoples Commissars of the Russian SFSR, or Russian Premier, from 1943 to 1946. Kosygin was responsible for the economic administration of the Soviet Union, and for several relatively liberal reforms in areas of domestic and external policies. Kosygin retired in 1980 due to bad health and was replaced by Nikolai Tikhonov.

Kosygin was born in the city of St. Petersburg in 1904 to a Russian working class family. He was conscripted into the labor army during the Russian Civil War, and after the Red Army's demobilisation in 1921, left to work in Siberia as an industrial manager. He returned to Leningrad in the early 1930s, working his way up the Soviet hierarchy. During the Great Patriotic War (World War II) he was a member of the State Defense Committee and was tasked with moving Soviet industry out of territories soon to be overrun by the German military. In the aftermath of the war Kosygin served as Minister of Finance for a year before becoming Minister of the Ministries of Light Industry and Light and Food Industry. One year before Stalin's death in 1952, he removed Kosygin from the politburo, purposely weakening his position within the Soviet hierarchy.

After the power struggle triggered by Stalin's death in 1953, Nikita Khrushchev became the new leader. On 20 March 1959, Kosygin was appointed to the position of Chairman of the State Planning Committee (Gosplan), a post he would hold for little more than a year. But by that time Kosygin had become a First Deputy of the Council of Ministers. After Khrushchev was ousted as leader in 1964, Kosygin was made Premier and Leonid Brezhnev made First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Kosygin, along with Brezhnev and Nikolai Podgorny, the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet, was part of the new "collective leadership" (later known as the All-People's Government). Kosygin became one of two major power players within the Soviet hierarchy, the other being Brezhnev, and was able to initiate the failed 1965 economic reform, usually referred to simply as the Kosygin reform. This reform, along with his more open stance on solving the Prague Spring, made Kosygin one of the most liberal members of the top leadership.

Some

of Kosygin's policies were seen as too radical, particularly by the

more conservative politburo members, who had a majority in the

politburo. They were, however, never able to depose Kosygin as Premier,

even if he and Brezhnev had major strains in their relationships to

each other. During most of the 1970s, Brezhnev had consolidated enough

power to stop any reform minded attempts by Kosygin. In 1980 Kosygin

retired from office due to bad health, and he died two months later on

18 December 1980. Kosygin was born into a Russian working class family consisting of his father and mother Nikolai Lenin and Matron Alexandrovna and his siblings. The family lived in St. Petersburg. Kosygin was baptised one month after his birth on 7 March. As many like him, he was conscripted into a labor army to fight with the Bolsheviks in the Russian Civil War. After the demobilisation of the Red Army in 1921, Kosygin attended the Leningrad Co-operative Technical School and found work in the system of consumer co-operatives in Novosibirsk, Siberia. When asked why he worked in cooperative sector of the economy, Kosygin replied, referrnig to Vladimir Lenin's slogan,; "Co-operation – the path to socialism!". He'd stay there for six years, applying for a membership in the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1927, he returned to Leningrad in 1930 to study at the Leningrad Textile Institute; he graduated five years later in 1935. After his graduation he got work as a director of a textile mill. Three years later Kosygin was elected Chairman of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Soviets of Working People's Deputies by the Leningrad Communist Party, and the following year he was appointed People's Commissar for Textile and Industry and earned a seat in the Central Committee. In 1940 he became a Deputy Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars and from 1943 to 1946 became Chairman of the Council of Peoples' Commissars of the Russian SFSR. Kosygin worked for the State Defense Committee during the Great Patriotic War. As Deputy Chairman of the Council of Evacuation his task was to evacuate industry from territories soon to be overrun by the Germans. He broke the Leningrad Blockade by organising the construction of a supply route and pipeline on the bottom of Lake Lagoda. From 1946 and onwords, Kosygin held top party positions within the Soviet hierarchy. He was a candidate member of the Politburo from 1946 to 1949 becoming a full-member during the end of Joseph Stalin's rule, but lost his seat in 1952. He briefly served as Minister of Finance in 1948 and then as Minister of Light Industry from 1949 to 1953. His administration skills had led to Stalin taking him under his wing. Stalin shared certain information with Kosygin, such as how much the families of Vyacheslav Molotov, Anastas Mikoyan and Lazar Kaganovich possessed, spent and paid their staff. It should be noted that a Politburo earned a modest salary by Soviet standards but

enjoyed unlimited access to consumer goods. He was therefore sent to

each home to put their houses in "proper order". Assignments such as

these made Kosygin unpopular with certain members of the Soviet

leadership. Kosygin told his son-in-law Mikhail Gvishiani, an NKVD officer, of the accusations leveled against his co-worker Nikolai Voznesensky, chairman of the Gosplan and Deputy Premier, because of his possessions of firearms. Gvishiani and Kosygin threw all the weapons they possessed into a lake

and searched both their houses for any listening devices. They found

one at Kosygin's house, but it might have been installed to spy on

Marshal Georgy Zhukov who lived there before him. According to his memoirs, Kosygin never left his home without reminding his wife what to do if he did not return. After two years of living in fright they reached the conclusion that Stalin would not harm them. Kosygin, along with Alexey Kuznetsov and Voznesensky formed a Troika in

the aftermath of the war, with all three being promoted up the Soviet

hierarchy by high standing officials, such as Stalin for example. It is

rumoured that Lavrentiy Beria and Georgy Malenkov were plotting against them, which led to the Leningrad Affair in

1950 which consisted of several fabricated criminal charges against

Kuznetsov and Voznesensky. Both Kuznetsov and Voznesensky were

sentenced to "collective sentencing", and were executed. Kosygin's

life, who was connected to Kuznetsov through marriage, was hanging by a

thread. How or why Kosygin survived the show trials has been left unexplained, but he, as some jokes say, "must have drawn a lucky lottery ticket". Nikita Khrushchev blamed

Beria and Malenkov for the innocent deaths of Kuznetsov and

Voznesensky, accusing Malenkov in 1957 to have been plotting against

them so that either he or Beria could succeed Stalin upon his death. Following

Stalin's death in March 1953 Kosygin was demoted but as a staunch ally

of Khrushchev his career soon turned around. While never one of

Khrushchev's protëgës, he quickly moved up the party ladder

and was promoted to head of the State Planning Committee and became Khrushchev's First Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers in 1960 and regained his old seat in the politburo. When Khrushchev was dismissed as leader in October 1964, Kosygin took over Khrushchev's position as Premier in what initially was a "collective leadership" with Leonid Brezhnev as General Secretary and Anastas Mikoyan, and later Nikolay Podgorny, as Chairman of the Presidium. The new politburo was more conservative than that under Khrushchev. Kosygin, along with Andrei Kirilenko and Nikolai Podgorny, were the most liberal while Brezhnev, Kirill Mazurov and Arvīds Pelše belonged to the moderate faction. Mikhail Suslov retained his leadership of the stalinist wing

of the party. Early in Kosygin's tenure, the Brezhnev - Kosygin attempt

at creating stability was failing on various fronts. From 1969 – 1970

discontent within the Soviet leadership had grown to such a level that

some started to doubt Soviet policy and actions in recent years;

examples include the handling of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia (which Kosygin initially resisted), the decline in agricultural production, the Sino - Soviet border conflict (advocated restraint), the Vietnam War and

the Soviet - American talks on the limitation of strategic missiles.

There were held two summit conferences between the US and USSR, the Warsaw Pact Summit Conference and the Moscow Summit Conference; both failed at gaining support for Soviet policies. By 1970 these differences had not been resolved and Brezhnev postponed the 24th party congress and the Ninth Five-Year Plan.

The delay in resolving these issues led to rumours circulating Soviet

society that Kosygin, or even Brezhnev, would lose their posts to

Podgorny. By March 1971 however it became apparent that Brezhnev was

the leader of the country, with Kosygin as the spokesman of the

five-year plan and Podgorny becoming an even more important member of

the "collective leadership" than before. Kosygin

would prove to be a very competent administrator, with the Soviet

standard of living rising considerably due to his moderately reformist

policy. Kosygin would later challenge Brezhnev on the rights of the general secretary to

represent the country abroad; a function Kosygin believed should fall

into the hands of the Premier, a common trait in non-communist

countries. This was actually implemented for a short period of time, which led Henry A. Kissinger to believe that Kosygin was the leader of the Soviet Union. During this period, Kosygin acted as a mediator between India and Pakistan in 1966 and got both nations to sign the Tashkent Declaration and later became the chief spokesman on the issue of arms control. In retrospect, many of Kosygin's co-workers felt he carried out his work "stoically", but lacked the "enthusiasm" that went with it, and therefor never developed a real taste for international politics. The Sino - Soviet split chagrined

Kosygin a great deal, and for a while refused to accept its

irrevocability; he briefly visited Beijing in 1969 due to the increase

of tension between the USSR and the People's Republic of China.

He said, in a close knit circle, that; "We are communists and they are

communists. It is hard to believe we will not be able to reach an

agreement if we met face to face". Kosygin who had been the chief negotiator with the First World during the 1960s, was hardly to be seen outside the Second World after Brezhnev strengthened his position within the Politburo and due to Andrey Gromyko's dislike of Kosygin meddling into his ministerial affairs. Like Khrushchev before him, Kosygin tried to reform the command economy within a communist framework. In 1965, Kosygin initiated the Soviet economic reform widely

referred to as the "Kosygin reform". Kosygin sought to make Soviet

industry more efficient by including some market measures seen in the

west such as profit making – and the quantity of production, increasing incentives for managers and workers, and freeing managers from centralised state bureaucracy. The

reform had already been proposed to Khrushchev in 1964, who evidently

liked it and took some preliminary steps to implement it. Brezhnev

allowed the reform to proceed, because the Soviet economy was entering

a period of low growth. The reform, in its testing phase, was applied to 336 enterprises in light industry. The reform had originated from Soviet economist Evsei Liberman.

Liberman's work influenced him, but Kosygin had overestimated the

Soviet administrative machine to develop the economy. This led to

"corrections" to some of Liberman's more controversial beliefs of decentralisation. The changes brought on by Kosygin to Liberman's original vision led, according to critics, the reform to fail. Kosygin,

who had for a long time been conscious of the West's superiority,

believed the key to catching up with them was decentralisation, semi-public companies and

cooperatives. His reform sought for a gradual change from a

"state administered economy" to an economy were "the state restricts

itself to guiding enterprises". Kosygin also believed in various forms

of property and management. To his disgruntlement, Khrushchev had fully

nationalised all Soviet cooperatives and Brezhnev hampered any genuine

discussion on the topic taking. Kosygin criticised Brezhnev's defence

and foreign aid policy, believing the expenditures were too heavy of a

burden for the economy. The reform was implemented, but showed several malfunctions and inconsistencies early on. With

the hostility towards the reform growing, the grim results and

Kosygin's reformist stance led to a popular backlash against him.

Kosygin lost most of the privileges he had enjoyed before the reform,

but Brezhnev was never able to remove him from the office of Chairman

of the Council of Ministers, despite his weakened position. The

salary for Soviet citizens increased abruptly almost 2.5 times. Real

wages in 1980 amounted to 232.7 rubles, whereas 166.3 rubles before the

reform. The first period, 1960 – 1964 is characterised by four years of

low growth, while the second period, 1965 – 1981 had a stronger growth

rate. The second period vividly demonstrated the success of the Kosygin

reform, with the average annual growth in retail turnover being 11.2

billion rubles, 1.8 times higher than in the first period and 1.2 times

higher than the third period (1981 – 1985). Consumption of goods and

daily demand also increased. The consumption of home appliances such as refrigerators greatly

increased, increasing from a low 109 in 1964 to 440 thousand units by

1973, but declined during the reversal of the reform. Car production

increased, but would continue to increase until the late 1980s, this

can be explained by the fact that the Soviet leadership under pressure,

sought to provide more attractive goods for Soviet consumers. The

removal of Nikita Khrushchev in 1964 signalled the end of his "housing revolution".

The truth is that the input declined already between 1960 – 64 to an

average 1.63 million square meters. Following the sudden sharp

decrease, it was once again followed by a sharp increase between

1965 – 66, then again a sudden decrease just to be followed up by a

steady growth (average annual growth rate being 4.26 million square

meters). This came largely to the expense of businesses. While the

housing shortages were never fully resolved, and still remains a

problem in present-day Russia, the reform managed to overcome the

negative trend and renew growth of housing construction. The Eighth Five-Year Plan (1965 – 1970)

is considered to be one of the most successful years for the Soviet

economy and the most successful when it comes to consumer production. With this information, many historians have concluded that the reform, while having its errors, improved the standard of living dramatically amongst Soviet households. In

the aftermath of his failed reform, Kosygin used the rest of his life

to improve the economic administration through the modification of the

targets, adopted various programs to improve food security and to

ensure the future intensification of production. These reforms, however, failed to improve the economic conditions in the country.

By

the early-to-mid 1970s Brezhnev had established a strong enough power

base to effectively become supreme leader, however, Kosygin was to

retain his position until 1980 when he resigned due to bad health. Early

signs in the 1970s showed that Brezhnev had taken full control over

both party and government activity, and Brezhnev had been able to

weaken Kosygin considerably. Kosygin's presentation to the 25th party congress is

seen as final proof that Kosygin lost the power struggle to Brezhnev.

The Tenth Five Year Plan was less ambitious than its predecessors, with

targets of national industrial growth being no higher than what the

rest of the world had already achieved. Soviet agriculture would

receive a share investment of 34 percent, even if it counted for only 3

percent of the Soviet GDP. A share much larger than its proportional

contribution to the Soviet economy. Kosygin was further pushed aside when Brezhnev published his memoirs which stated that Brezhnev, not Kosygin, was in charge of all major economic decisions. Brezhnev

had blocked any future talks on economic reforms within the party and

government apparatus, and information regarding the reform of 1965 was

suppressed. During an official visit by an Afghan delegation, Kosygin and Andrei Kirilenko criticised the Afghan leaders Nur Muhammad Taraki and Hafizullah Amin for stalinist repressionist behavior. An intervention in Afghanistan would strain the USSR's foreign relations with the First World, most notably West Germany.

He did promise to send more economic and military aid, but rejected any

proposal regarding a possible Soviet intervention. In an address to the

Afghan leadership, Kosygin is quoted as saying: "We

should tell Taraki and Amin to change their tactics. They still

continue to execute those people who disagree with them. They are

killing nearly all of the Parcham leaders, not only the highest rank, but of the middle rank, too". Rumours started circulating within the top circles, and on the streets, that Kosygin would retire due to bad health. In 1976 Kosygin suffered his first heart attack.

After this incident, it is said that Kosygin changed from having a

vibrant personality to becoming tired, fed up and losing the will to

continue his work. He twice filled a letter of resignation prior to 1980 but both were turned down. During Kosygin's sick leave, Brezhnev appointed Nikolai Tikhonov as new First Deputy of the Council of Ministers.

Tikhonov was a conservative just as Brezhnev and his entourage were;

therefore, when he took command over the Soviet economy, Kosygin was

reduced to a standby figure. During a Central Committee plenum in June 1980, the Soviet economic development plan was outlined by Tikhonov and not Kosygin. In

October 1980 Kosygin was again hospitalised. During his stay Kosygin

wrote a very brief letter of resignation; the following day he was

deprived of all government protection, communication, cars and other

luxury goods he had earned during his political life. Kosygin died

alone on 18 December 1980, none of his Politburo colleagues, former

aides or security guards visited him. At the very end of his life,

Kosygin feared the complete failure of the Eleventh Five-Years Plan claiming

that the sitting leadership were reluctant to reform the stagnent

Soviet economy. Kosygin died on 18 October 1980, his death was not

announced until three days after his death; Brezhnev was celebrating

his own birthday on 19 December. He was buried in Red Square, Moscow. A state funeral was conducted, and Kosygin was honored by his peers; Brezhnev, Yuri Andropov and Tikhonov laid an urn containing his ashes at the Kremlin Wall. Kosygin's moderate 1965 reform, as with Nikita Khrushchev's thaw, radicalised the Soviet reform movement. While Leonid Brezhnev was content with maintaining the centralised structure of the Soviet planned economy; Kosygin attempted to revitalise with reforms which would decentralise the system. Following Brezhnev's death in 1982 the reform movement was split between Yuri Andropov's path of discipline and control, and Gorbachev's liberalisation of all aspects of public life. Compared

to other Soviet officials Kosygin stood out as a pragmatic and

relatively independent leader. In a description given by an anonymous high-ranking GRU official,

Kosygin is described as "a lonely and somewhat tragic figure" who

"understood our faults and shortcomings of our situation in general and

those in our Middle East policy

in particular, but, being a highly restrained man, he preferred to be

cautious." Another anonymous, this time an old co-worker of Kosygin,

said; "He always had an opinion of his own, and defended it. He was a

very alert man, and performed brilliantly during negotiations. He was

able to cope quickly with the material that was totally new to him. I

have never seen people of that calibre afterwards." Gvishiani, a Russian historian, concluded that "Kosygin survived both [Joseph] Stalin and Khrushchev, but did not manage to survive Brezhnev." In an official state visit Kosygin struck the Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau of

being "Khrushchev without the rough edges, a fatherly man who was the

forerunner of Mikhail Gorbachev". Moreover, he noted that Kosygin was

willing to discuss issues so long that the Soviet position was not

tackled head-on. Kosygin was viewed with sympathy by the Soviet people, and is at the present seen as an important figure in both Russian and Soviet history.

During his lifetime, Kosygin received seven Orders and two Awards by the Soviet state. During a state visit to Peru in the 1970s with Leonid Brezhnev and Andrei Gromyko all three of them were awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of the Sun by President Francisco Morales Bermúdez.