<Back to Index>

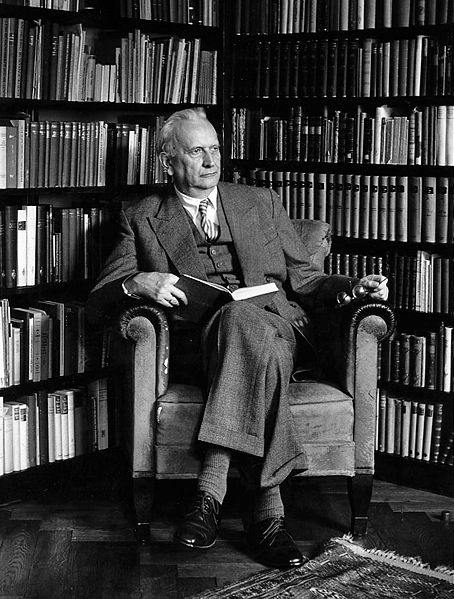

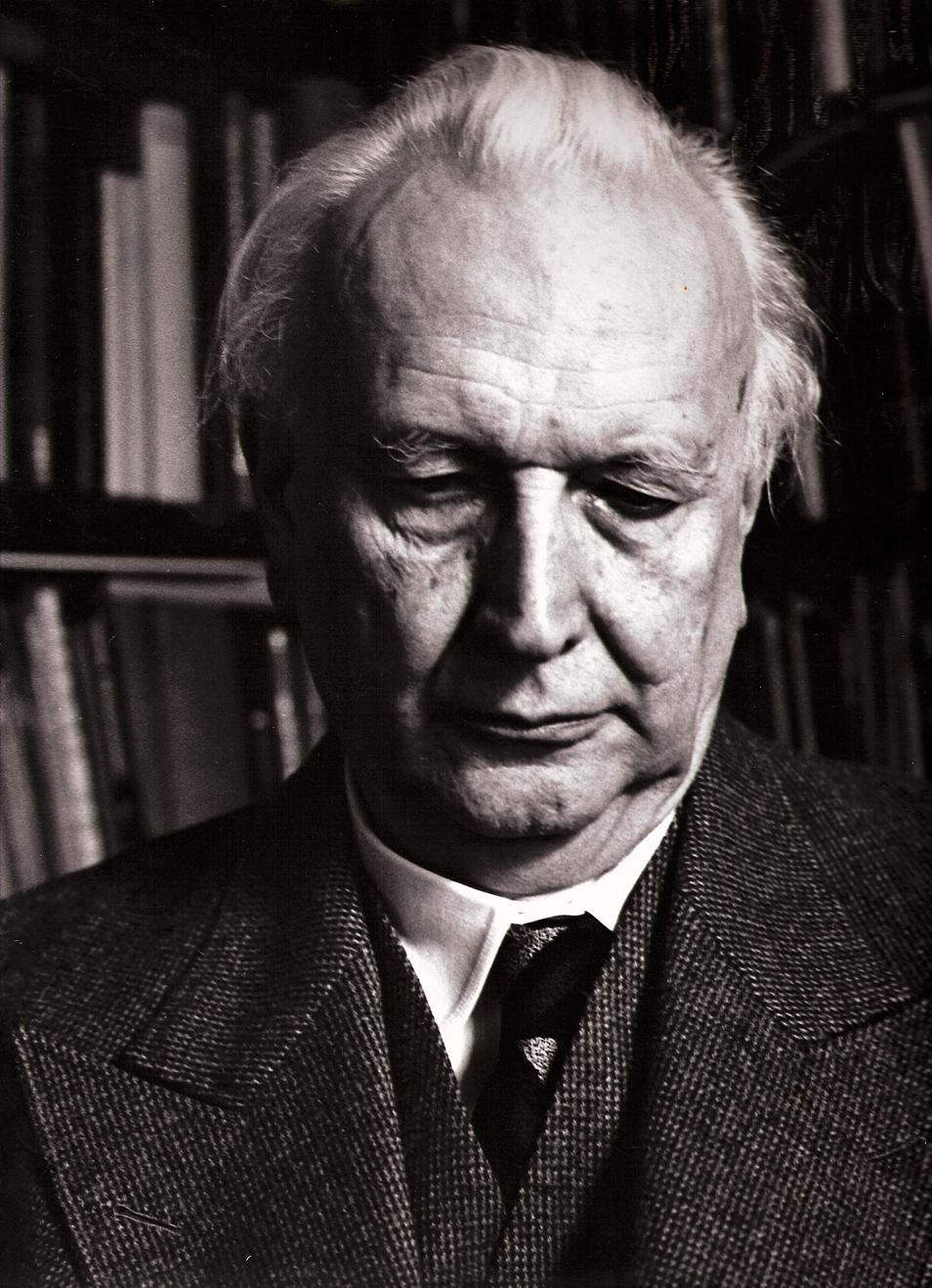

- Psychiatrist and Philosopher Karl Theodor Jaspers, 1883

- Painter Hendrik Willem Mesdag, 1831

- 5th Edo Shogun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, 1646

PAGE SPONSOR

Karl Theodor Jaspers (February 23, 1883 – February 26, 1969) was a German psychiatrist and philosopher who had a strong influence on modern theology, psychiatry and philosophy. After being trained in and practicing psychiatry, Jaspers turned to philosophical inquiry and attempted to discover an innovative philosophical system. He was often viewed as a major exponent of existentialism in Germany, though he did not accept this label.

Jaspers was born in Oldenburg in 1883 to a mother from a local farming community, and a jurist father. He showed an early interest in philosophy, but his father's experience with the legal system undoubtedly influenced his decision to study law at university. It soon became clear that Jaspers did not particularly enjoy law, and he switched to studying medicine in 1902 with a thesis about criminology.

Jaspers graduated from medical school in 1909 and began work at a psychiatric hospital in Heidelberg where Emil Kraepelin had worked some years earlier. Jaspers became dissatisfied with the way the medical community of the time approached the study of mental illness and set himself the task of improving the psychiatric approach. In 1913 Jaspers gained a temporary post as a psychology teacher at Heidelberg University. The post later became permanent, and Jaspers never returned to clinical practice. During this time Jaspers was a close friend of the Weber family (Max Weber also having held a professorship at Heidelberg).

At the age of 40 Jaspers turned from psychology to philosophy, expanding on themes he had developed in his psychiatric works. He became a renowned philosopher, well respected in Germany and Europe.

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, Jaspers was considered to have a "Jewish taint" (jüdische Versippung, in the jargon of the time) due to his Jewish wife, and was forced to retire from teaching in 1937. In 1938 he fell under a publication ban as well. Many of his long time friends stood by him, however, and he was able to continue his studies and research without being totally isolated. But he and his wife were under constant threat of removal to a concentration camp until March 30, 1945, when Heidelberg was liberated by American troops.

In 1948 Jaspers moved to the University of Basel in Switzerland. He remained prominent in the philosophical community until his death in Basel in 1969.

Jaspers'

dissatisfaction with the popular understanding of mental illness led

him to question both the diagnostic criteria and the methods of

clinical psychiatry. He published a revolutionary paper in 1910 in

which he addressed the problem of whether paranoia was

an aspect of personality or the result of biological changes. Whilst

not broaching new ideas, this article introduced a new method of study.

Jaspers studied several patients in detail, giving biographical

information on the people concerned as well as providing notes on how

the patients themselves felt about their symptoms. This has become

known as the biographical method and now forms the mainstay of modern psychiatric practice.

Jaspers set about writing his views on mental illness in a book which he published in 1913 as General Psychopathology.

The two volumes which make up this work have become a classic in the

psychiatric literature and many modern diagnostic criteria stem from

ideas contained within them. Of particular importance, Jaspers believed

that psychiatrists should diagnose symptoms (particularly of psychosis) by their form rather than by their content. For example, in diagnosing a hallucination,

the fact that a person experiences visual phenomena when no sensory

stimuli account for it (form) assumes more importance than what the

patient sees (content). Jaspers felt that psychiatrists could also diagnose delusions in

the same way. He argued that clinicians should not consider a belief

delusional based on the content of the belief, but only based on the

way in which a patient holds such a belief.

Jaspers also distinguished between primary and secondary delusions. He defined primary delusions as autochthonous meaning arising without apparent cause, appearing incomprehensible in terms of

normal mental processes. (This is a slightly different use of the term

autochthonous than its usual medical or sociological meaning of

indigenous.) Secondary delusions, on the other hand, he classified as

influenced by the person's background, current situation or mental

state. Jaspers

considered primary delusions as ultimately 'un-understandable,' as he

believed no coherent reasoning process existed behind their formation.

This view has caused some controversy, and the likes of R.D. Laing and Richard Bentall (1999)

have criticised it, stressing that taking this stance

can lead therapists into the complacency of assuming that because they

do not understand a patient, the patient is deluded and further

investigation on the part of the therapist will have no effect. Huub

Engels (2009) argues that schizophrenic speech disorder may be

understandable as Emil Kraepelin's dream speech is understandable.

Most commentators associate Jaspers with the philosophy of existentialism, in part because he draws largely upon the existentialist roots of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard, and in part because the theme of individual freedom permeates his work.

In Philosophy (3 vols, 1932), Jaspers gave his view of the history of philosophy and introduced his major themes. Beginning with modern science and empiricism, Jaspers points out that as we question reality, we confront borders that an empirical (or scientific) method simply cannot transcend. At this point, the individual faces a choice: sink into despair and resignation, or take a leap of faith toward what Jaspers calls Transcendence. In making this leap, individuals confront their own limitless freedom, which Jaspers calls Existenz, and can finally experience authentic existence. Transcendence (paired with the term The Encompassing in later works) is, for Jaspers, that which exists beyond the world of time and space. Jaspers' formulation of Transcendence as ultimate non-objectivity (or no-thing-ness) has led many philosophers to argue that ultimately, Jaspers became a monist, though Jaspers himself continually stressed the necessity of recognizing the validity of the concepts both of subjectivity and of objectivity.

Although he rejected explicit religious doctrines, including the notion of a personal God, Jaspers influenced contemporary theology through his philosophy of transcendence and the limits of human experience. Mystic Christian traditions influenced Jaspers himself tremendously, particularly those of Meister Eckhart and of Nicholas of Cusa. He also took an active interest in Eastern philosophies, particularly Buddhism, and developed the theory of an Axial Age, a period of substantial philosophical and religious development. Jaspers also entered public debates with Rudolf Bultmann, wherein Jaspers roundly criticized Bultmann's "demythologizing" of Christianity.

Jaspers also wrote extensively on the threat to human freedom posed by modern science and modern economic and political institutions. During World War II, he had to abandon his teaching post because his wife was Jewish. After the war he resumed his teaching position, and in his work The Question of German Guilt he unabashedly examined the culpability of Germany as a whole in the atrocities of Hitler's Third Reich.

Jaspers's major works, lengthy and detailed, can seem daunting in their complexity. His last great attempt at a systematic philosophy of Existenz — Von Der Wahrheit (On Truth) — has not yet appeared in English. However, he also wrote accessible and entertaining shorter works, most notably Philosophy is for Everyman.

Commentators often compare Jaspers' philosophy to that of his contemporary, Martin Heidegger. Indeed, both sought to explore the meaning of being (Sein) and existence. While the two did maintain a brief friendship, their relationship deteriorated - due in part to Heidegger's affiliation with the Nazi party, but also due to the (probably over-emphasized) philosophical differences between the two.

The two major proponents of phenomenological hermeneutics, Paul Ricoeur (a student of Jaspers) and Hans-Georg Gadamer (Jaspers's successor at Heidelberg) both display Jaspers's influence in their works.

Other important work appeared in Philosophy and Existence (1938). For Jaspers, the term "existence" (Existenz) designates the indefinable experience of freedom and possibility; an experience which constitutes the authentic being of individuals who become aware of "the encompassing" by confronting suffering, conflict, guilt, chance, and death.

Jaspers valued humanism and the continuity of integral cultural tradition in political spheres. He strongly opposed totalitarian despotism and warned about the increasing tendency towards technocracy, or a regime that regarded humans as mere instruments of science or ideological goals. He was also skeptical of majoritarian democracy. Thus, he supported a form of governance that guaranteed individual freedom and limited government yet was rooted in authentic tradition and guided by an intellectual elite.

Jaspers held Kierkegaard and Nietzsche to be two of the most important figures in post-Kantian philosophy. In his compilation, The Great Philosophers, he wrote:

I approach the presentation of Kierkegaard with some trepidation. Next to Nietzsche, or rather, prior to Nietzsche, I consider him to be the most important thinker of our post-Kantian age. With Goethe and Hegel, an epoch had reached its conclusion, and our prevalent way of thinking - that is, the positivistic, natural-scientific one - cannot really be considered as philosophy.

Jaspers also questions whether the two philosophers could be taught. For Kierkegaard, at least, Jaspers felt that Kierkegaard's whole method of indirect communication precludes any attempts to properly expound his thought into any sort of systematic teaching. Though Jaspers was certainly indebted to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, he also owes much to more traditional philosophers, especially Kant and Plato. Walter Kaufmann argues in "From Shakespeare to Existentialism" that, though Jaspers was certainly indebted to Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, he was closest to Kant's philosophy.

Jaspers is too often seen as the heir of Nietzsche and Kierkegaard to whom he is in many ways less close than to Kant... the Kantian antinomies and Kant's concern with the realm of decision, freedom, and faith have become exemplary for Jaspers. And even as Kant "had to do away with knowledge to make room for faith," Jaspers values Nietzsche in large measure because he thinks that Nietzsche did away with knowledge, thus making room for Jaspers' philosophic faith"...

This is supported by Jaspers' essay "On My Philosophy",

"While I was still at school Spinoza was the first. Kant then became the philosopher for me and has remained so... Nietzsche gained importance for me only late as the magnificent revelation of nihilism and the task of overcoming it."