<Back to Index>

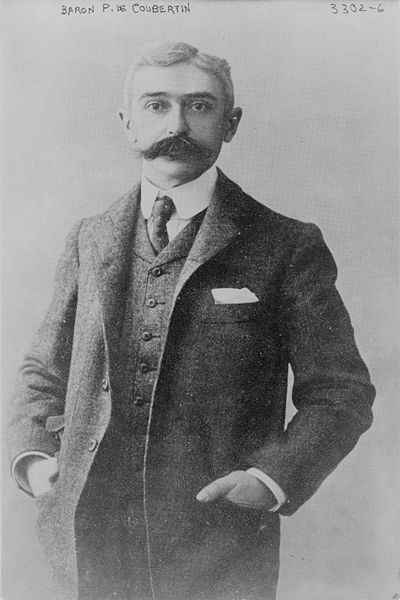

- Historian Pierre Frédy, Baron de Coubertin, 1863

- Architect Robert Arthur Lawson, 1833

- Taiping Rebel Hong Xiuquan, 1814

PAGE SPONSOR

Pierre Frédy, Baron de Coubertin (1 January 1863 – 2 September 1937) was a French pedagogue and historian, founder of the International Olympic Committee, and considered father of the modern Olympic Games. Born into a French aristocratic family, he became an academic and studied a broad range of topics, most notably education and history.

Pierre Frédy was born in Paris on 1 January 1863 into an established aristocratic family. He was the fourth child of Baron Charles Louis Frédy, Baron de Coubertin and Marie-Marcelle Gigault de Crisenoy. Family tradition held that the Frédy name had first arrived in France in the early 15th century, and the first recorded title of nobility granted to the family was given by Louis XI to an ancestor, also named Pierre de Frédy, in 1477. But other branches of his family tree delved even further into French history, and the annals of both sides of his family included nobles of various stations, military leaders, and associates of kings and princes of France. His father Charles was a staunch royalist and accomplished artist whose paintings were displayed and given prizes at the Parisian salon, at least in those years when he was not absent in protest of the rise to power of Louis Napoleon. His paintings often centered around themes related to the Roman Catholic Church, classicism, and nobility, which reflected those things he thought most important. In a later semi-fictional autobiographical piece called Le Roman d'un rallié, Coubertin describes his relationship with both his mother and his father as having been somewhat strained during his childhood and adolescence. His memoirs elaborated further, describing as a pivotal moment his disappointment upon meeting Henri, Count of Chambord, who the elder Coubertin believed to be the rightful king.

Coubertin grew up in a time of profound change in France; as a young man he would have seen and heard news of France's defeat during the Franco - Prussian War, the Paris Commune, and the establishment of the French Third Republic, and would later marry in the midst of the Dreyfus Affair. But while these events proved the setting to his childhood, his school experiences were just as formative. In October 1874, his parents enrolled him in a new Jesuit school called Externat de la rue de Vienne, which was still under construction for his first five years there. While many of the school's attendees were day students, Coubertin boarded at the school under the supervision of a Jesuit priest, which his parents hoped would instill him with a strong moral and religious education. There, he was among the top three students in his class, and was an officer of the school's elite academy made up of its best and brightest. This suggests that despite his rebelliousness at home, Coubertin adapted well to the strict rigors of a Jesuit education.

As

an aristocrat, Coubertin had a number of career paths from which to

choose, including potentially prominent roles in the military or

politics. But he chose instead to pursue a career as an intellectual,

studying and later writing on a broad range of topics, including

education, history, literature, and sociology. The

subject which he seems to have been most deeply interested in was

education, and his study focused in particular on physical education

and the role of sport in schooling. In 1883, he visited England for the first time, and studied the program of physical education instituted by Thomas Arnold at the Rugby School.

Coubertin credited these methods with leading to the expansion of

British power during the 1800s and advocated for their use in French

institutions. The inclusion of physical education in the curriculum of

French schools would become an ongoing pursuit and passion of

Coubertin's. In

fact, Coubertin is thought to have exaggerated the importance of sport

to Thomas Arnold, whom he viewed as “one of the founders of athletic

chivalry”. The character reforming influence of sport with which

Coubertin was so impressed, is more likely to have originated in Tom

Brown’s School Days rather than exclusively in the ideas of Arnold

himself. Nonetheless, Coubertin was an enthusiast in need of a cause

and he found it in England and in Thomas Arnold. “Thomas

Arnold, the leader and classic model of English educators,” wrote

Coubertin, “gave the precise formula for the role of athletics in

education. The cause was quickly won. Playing fields sprang up all over

England”. Intrigued

by what he had read about English public schools, in 1883, at the age

of twenty, Coubertin went to Rugby and to other English schools to see

for himself. He described the results in a book, L’Education en

Angleterre, which was published in Paris in 1888. This hero of his book

is Thomas Arnold and on his second visit in 1886, he reflected on

Arnold’s influence in the chapel at Rugby School. What

Coubertin saw on the playing fields of Rugby and the other English

schools he visited was how “organised sport can create moral and social

strength”. Not

only did organised games help to set the mind and body in equilibrium,

it also prevented the time being wasted in other ways. First developed

by the ancient Greeks, it was an approach to education that he felt the

rest of the world had forgotten and to whose revival he was to dedicate

the rest of his life. As a historian and a thinker on education, Coubertin romanticized ancient Greece. Thus, when he began to develop his theory of physical education, he naturally looked to the example set by the Athenian idea of the gymnasium,

a training facility that simultaneously encouraged physical and

intellectual development. He saw in these gymnasia what he called a

triple unity between old and young, between disciplines, and between

different types of people, meaning between those whose work was

theoretical and those whose work was practical. Coubertin advocated for

these concepts, this triple unity, to be incorporated into schools. But

while Coubertin was certainly a romantic, and while his idealized

vision of ancient Greece would lead him later to the idea of reviving

the Olympic Games, his advocacy for physical education was based on

practical concerns as well. He believed that men who received physical

education would be better prepared to fight in wars, and better able to

win conflicts like the Franco - Prussian War,

in which France had been humiliated. Additionally, he also saw sport as

democratic, in that sports competition crossed class lines, although it

did so without causing a mingling of classes, which he did not support. Unfortunately

for Coubertin, his efforts to incorporate more physical education into

French schools failed. The failure of this endeavor, however, was

closely followed by the development of a new idea, the revival of the ancient Olympic Games, the creation of a festival of international athleticism. He was particularly fond of rugby and was the referee of the first ever French championship rugby union final on 20 March 1892 between Racing Club de France and Stade Français.

Some

historians describe Coubertin as the instigator of the modern Olympic

movement, a man whose vision and political skill led to the revival of

the Olympics Games which had been practiced in antiquity. The ancient Olympic Games were held every four years in the Greek city of Olympia, in the Kingdom of Elis,

from 776 BCE through either 261 or 393 AD. While there were a number of

other ancient games celebrated in Greece during this time period,

including the Pythian, Nemean, and Isthmian Games, Coubertin idealized the Olympic Games as the ultimate ancient athletic competition. Thomas

Arnold, the Head Master of Rugby School, was an important influence on

Coubertin's thoughts about education, but his meetings with Dr. William Penny Brookes also

influenced his thinking about athletic competition to some extent. A

trained physician, Brookes believed that the best way to prevent

illness was through physical exercise. In 1850, he had initiated a

local athletic competition that he referred to as "Meetings of the Olympian Class" at the Gaskell recreation ground at Much Wenlock, Shropshire. Along with the Liverpool Athletic Club,

who began holding their own Olympic Festival in the 1860s, Brookes

created a National Olympian Association which aimed to encourage such

local competition in cities across Britain. These efforts were largely

ignored by the British sporting establishment. Brookes also maintained

communication with the government and sporting advocates in Greece,

seeking a revivial of the Olympic Games internationally under the

auspices of the Greek government. There, the philanthropist brothers Evangelos and Konstantinos Zappas had used their wealth to fund Olympics within Greece, and paid for the restoration of the Panathinaiko Stadium that was later used during the 1896 Summer Olympics. The efforts of Brookes to encourage the internationalization of these games came to naught. However,

Dr Brookes did organize a national Olympic Games in London, at Crystal

Palace, in 1866 and this was the first Olympics to resemble an Olympic

Games to be held outside of Greece. But

while others had created Olympic contests within their countries, and

broached the idea of international competition, it was Coubertin whose

work would lead to the establishment of the International Olympic Committee and the organization of the first modern Olympic Games. In

1888, Coubertin founded the Comite pour la Propagation des Exercises

Physiques more well known as the Comite Jules Simon. Coubertin's

earliest reference to the modern notion of Olympic Games criticises the

idea. The

idea for reviving the Olympic Games as an international competition

came to Coubertin in 1889, apparently independently of Brookes, and he

spent the following five years organizing an international meeting of

athletes and sports enthusiasts that might make it happen. Dr Brookes had organised a national Olympic Games that was held at Crystal Palace in London in 1866. In

response to a newspaper appeal, Brookes wrote to Coubertin in 1890, and

the two began an exchange of letters on education and sport. That

October, Brookes hosted the Frenchman at a special festival held in his

honor at Much Wenlock. Although he was too old to attend the 1894

Congress, Brookes would continue to support Coubertin's efforts, most

importantly by using his connections with the Greek government to seek

its support in the endeavor. While Brookes' contribution to the revival

of the Olympic Games was recognized in Britain at the time, Coubertin

in his later writings largely neglected to mention the role the

Englishman played in their development. He

did mention the roles of Evangelos Zappas and his cousin Konstantinos

Zappas, but drew a distinction between their founding of athletic

Olympics and his own role in the creation of an international contest. However,

Coubertin together with A. Mercatis, a close friend of Konstantinos,

encouraged the Greek government to utilise part of Konstantinos' legacy

to fund the 1896 Athens Olympic Games separately and in addition to the

legacy of Evangelos Zappas that Konstantinos had been executor of. Moreover, George Averoff was invited by the Greek government to fund the second refurbishment of the Panathinaiko Stadium that had already been fully funded by Evangelos Zappas forty years earlier. Coubertin's

advocacy for the Games centered on a number of ideals about sport. He

believed that the early ancient Olympics encouraged competition among

amateur rather than professional athletes, and saw value in that. The

ancient practice of a sacred truce in association with the Games might

have modern implications, giving the Olympics a role in promoting

peace. This role was reinforced in Coubertin's mind by the tendency of

athletic competition to promote understanding across cultures, thereby

lessening the dangers of war. In addition, he saw the Games as

important in advocating his philosophical ideal for athletic

competition: that the competition itself, the struggle to overcome

one's opponent, was more important than winning. Coubertin expressed this ideal thus: L'important

dans la vie ce n'est point le triomphe, mais le combat, l'essentiel ce

n'est pas d'avoir vaincu mais de s'être bien battu. The

important thing in life is not the triumph but the struggle, the

essential thing is not to have conquered but to have fought well. As

Coubertin prepared for his Congress, he continued to develop a

philosophy of the Olympic Games. While he certainly intended the Games

to be a forum for competition between amateur athletes, his conception

of amateurism was complex. By 1894, the year the Congress was held, he

publicly criticized the type of amateur competition embodied in English

rowing contests, arguing that its specific exclusion of working class

athletes was wrong. While he believed that athletes should not be paid

to be such, he did think that compensation was in order for the time

when athletes were competing and would otherwise have been earning

money. Following the establishment of a definition for an amateur

athlete at the 1894 Congress, he would continue to argue that this

definition should be amended as necessary, and as late as 1909 would

argue that the Olympic movement should develop its definition of

amateurism gradually. Along

with the development of an Olympic philosophy, Coubertin invested time

in the creation and development of a national association to coordinate

athletics in France, the Union des Sociétés Françaises de Sports Athlétiques (USFSA). In 1889, French athletics associations had grouped together for the first time and Coubertin founded a monthly magazine La Revue Athletique, the first French periodical devoted exclusively to athletics and modelled on The Athlete, an English journal established around 1862. Formed

by seven sporting societies with approximately 800 members, by 1892 the

association had expanded to 62 societies with 7,000 members. That

November, at the annual meeting of the USFSA, Coubertin first publicly

suggested the idea of reviving the Olympics. His speech met general

applause, but little commitment to the Olympic ideal he was advocating

for, perhaps because sporting associations and their members tended to

focus on their own area of expertise and had little identity as

sportspeople in a general sense. This disappointing result was prelude

to a number of challenges he would face in organizing his international

conference. In order to develop support for the conference, he began to

play down its role in reviving Olympic Games and instead promoted it as

a conference on amateurism in sport which, he thought, was slowly being

eroded by betting and sponsorships. This led to later suggestions that

participants were convinced to attend under false pretenses. Little

interest was expressed by those he spoke to during trips to the United States in 1893 and London in

1894, and an attempt to involve the Germans angered French gymnasts who

did not want the Germans invited at all. Despite these challenges, the

USFSA continued its planning for the games, adopting in its first

program for the meeting eight articles to address, only one of which

had to do with the Olympics. A later program would give the Olympics a

much more prominent role in the meeting. The congress was held on June 23, 1894 at the Sorbonne in Paris.

Once there, participants divided the congress into two commissions, one

on amateurism and the other on reviving the Olympics. A Greek

participant, Demetrius Vikelas,

was appointed to head the commission on the Olympics, and would later

become the first President of the International Olympic Committee.

Along with Coubertin, C. Herbert of Britain's Amateur Athletic Association and

W.M. Sloane of the United States helped lead the efforts of the

commission. In its report, the commission proposed that Olympic Games

be held every four years and that the program for the Games be one of

modern rather than ancient sports. They also set the date and location

for the first modern Olympic Games, the 1896 Summer Olympics in Athens, Greece, and the second, the 1900 Summer Olympics in

Paris. Coubertin had originally opposed the choice of Greece, as he had

concerns about the ability of a weakened Greek state to host the

competition, but was convinced by Vikelas to support the idea. The

commission's proposals were accepted unanimously by the congress, and

the modern Olympic movement was officially born. The proposals of the

other commission, on amateurism, were more contentious, but this

commission also set important precedents for the Olympic Games,

specifically the use of heats to narrow participants and the banning of

prize money in most contests. Following

the Congress, the institutions created there began to be formalized

into the International Olympic Committee (IOC), with Demetrius Vikelas

as its first President. The work of the IOC increasingly focused on

planning the 1896 Athens Games, and de Coubertin played a background

role as Greek authorities took the lead in logistical organization of

the Games in Greece itself, offering technical advice such as a sketch

of a design of a velodrome to

be used in cycling competitions. He also took the lead in planning the

program of events, although to his disappointment neither polo, football, or boxing were included in 1896. The

Greek organising committee had been informed that four foreign football

teams were to participate however not one foreign football team showed

up and despite Greek preparations for a football tournament it was

cancelled during the Games. The

Greek authorities were frustrated that he could not provide an exact

estimate of the number of attendees more than a year in advance. In

France, Coubertin's efforts to elicit interest in the Games among

athletes and the press met difficulty, largely because the

participation of German athletes angered French nationalists who

begrudged Germany their victory in the Franco - Prussian War. Germany

also threatened not to participate after rumors spread that Coubertin

had sworn to keep Germany out, but following a letter to the Kaiser denying

the accusation, the German National Olympic Committee decided to

attend. Coubertin himself was frustrated by the Greeks, who

increasingly ignored him in their planning and who wanted to continue

to hold the Games in Athens every four years, against de Coubertin's

wishes. The conflict was resolved after he suggested to the King of

Greece that he hold pan-Hellenic games in between Olympiads, an idea

which the King accepted, although Coubertin would receive some angry

correspondence even after the compromise was reached and the King did

not mention him at all during the banquet held in honor of foreign

athletes during the 1896 Games. Coubertin

took over the IOC presidency when Demetrius Vikelas stepped down after

the Olympics in his own country. Despite the initial success, the

Olympic Movement faced hard times, as the 1900 (in De Coubertin's own

Paris) and 1904 Games were both swallowed by World's Fairs, and

received little attention. The Paris Games were not organised by

Coubertin or the IOC nor were they called Olympics at that time. The

St. Louis Games was hardly internationalized and was an embarrassment. The 1906 Summer Olympics revived

the momentum, and the Olympic Games grew to become the world's most

important sports event. Coubertin created the modern pentathlon for the

1912 Olympics, and subsequently stepped down from his IOC presidency

after the 1924 Olympics in Paris, which proved much more successful

than the first attempt in that city in 1900. He was succeeded as

president, in 1925, by Belgian Henri de Baillet - Latour. Coubertin

remained Honorary President of the IOC until he died in 1937 in Geneva,

Switzerland. He was buried in Lausanne (the seat of the IOC), although,

in accordance with his will, his heart was buried separately in a

monument near the ruins of ancient Olympia.

Coubertin won the gold medal for literature at the 1912 Summer Olympics for his poem Ode to Sport.

In 1911, Pierre de Coubertin founded the inter-religious Scouting organisation Eclaireurs Français (EF) in France, which later merged to form the Eclaireuses et Eclaireurs de France.

Pierre

was the last person to the family name. In the words of his biographer

John MacAloon, "The last of his lineage, Pierre de Coubertin was the

only member of it whose fame would outlive him.

In

1895 Pierre de Coubertin had married Marie Rothan, the daughter of

family friends. The first-born, Jacques, became retarded after his

parents left him in the sun too long when he was a little child. Their

daughter suffered emotional disturbances, never married, and never

found peace in her life. Marie and Pierre tried to console themselves

with two nephews who became substitutes for their own children, but the

nephews were killed at the front in World War I. Marie died in 1963. Coubertin's

legacy has been criticized by a number of scholars. David C. Young, a

scholar of antiquity who has studied the ancient Olympic Games,

believes that Coubertin misunderstood the ancient Games and therefore

based his justification for the creation of the modern Games on false

grounds. Specifically, Young points to Coubertin's assertion that

ancient Olympic athletes were amateurs as incorrect. This

question of the professionalism of ancient Olympic athletes is a

subject of debate amongst scholars, with Young and others arguing that

the athletes were professional throughout the history of the ancient

Games, while other scholars led by Pleket argue that the earliest

Olympic athletes were in fact amateur, and that the Games only became

professionalized after about 480 BCE. Coubertin agreed with this latter

view, and saw this professionalization as undercutting the morality of

the competition. Further,

Young asserts that the effort to limit international competition to

amateur athletes, which Coubertin was a part of, was in fact part of

efforts to give the upper classes greater control over athletic

competition, removing such control from the working classes. Coubertin

may have played a role in such a movement, but his defenders argue that

he did so unconscious of any class repercussions.

However,

it is clear that his romanticized vision of the Olympic Games was

fundamentally different from that described in the historical record.

For example, de Coubertin's idea that winning was less important than

striving is at odds with the ideals of the Greeks. His assertion that

the Games were the impetus for peace was also an exaggeration; the

peace which he spoke of only existed to allow athletes to travel safely

to Olympia, and neither prevented the outbreak of wars nor ended

ongoing ones. Scholars

have critiqued the idea that athletic competition might lead to greater

understanding between cultures and, therefore, to peace. Christopher

Hill claims that modern participants in the Olympic movement may defend

this particular belief, "in a spirit similar to that in which the

Church of England remains attached to the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion,

which a Priest in that Church must sign." In other words, that they may

not wholly believe it but hold to it for historical reasons. Questions

have also been raised about the veracity of Coubertin's account of his

role in the planning of the 1896 Athens Games. According to Young,

either due to personal or professional distractions, Coubertin played

little role in planning, despite entreaties by Vikelas. Young also

suggests that the story about Coubertin's having sketched the velodrome

were untrue, and that he had in fact given an interview in which he

suggested he did not want Germans to participate, something he later

denied in a letter to the Kaiser. The Pierre de Coubertin medal (also known as the Coubertin medal or the True Spirit of Sportsmanship medal) is an award given by the International Olympic Committee to those athletes that demonstrate the spirit of sportsmanship in the Olympic Games.

This medal is considered by many athletes and spectators to be the

highest award that an Olympic athlete can receive, even greater than a

gold medal. The International Olympic Committee considers it as its

highest honor. A minor planet 2190 Coubertin discovered in 1976 by Soviet astronomer Nikolai Stepanovich Chernykh is named in his honor. The street where the Olympic Stadium in Montreal, Quebec, is located (which hosted the 1976 Summer Olympic Games)

was named after Pierre de Coubertin, giving the stadium the address

4549 Pierre de Coubertin Avenue. It is the only Olympic Stadium in the

world that lies on a street named after Coubertin. There are also two

schools in Montreal named after Pierre de Coubertin. He was portrayed by Louis Jourdan in the 1984 NBC miniseries, The First Olympics: Athens, 1896.