<Back to Index>

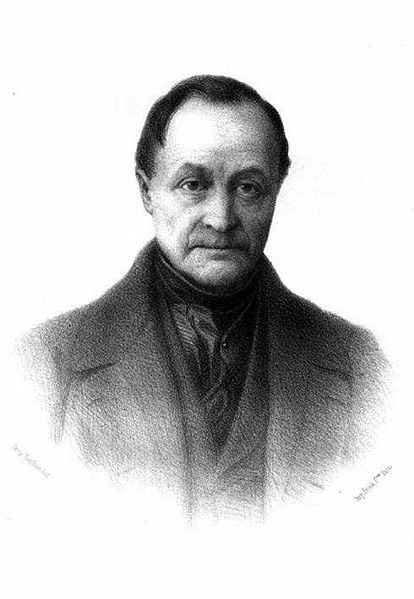

- Philosopher Auguste Comte, 1798

- Poet Edgar Allan Poe, 1809

- Magistrate Paolo Borsellino, 1940

PAGE SPONSOR

Auguste Comte (19 January 1798 – 5 September 1857) was a French philosopher, a founder of the discipline of sociology and of the doctrine of positivism. He may be regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term.

Strongly influenced by the Utopian socialist, Henri de Saint-Simon, Comte developed the positive philosophy in an attempt to remedy the social malaise of the French revolution, calling for a new social paradigm based on the sciences.

A relatively obscure figure today, Comte was of considerable influence

in 19th century thought, impacting the work of thinkers such as Karl Marx and John Stuart Mill. His version of sociologie and his notion of social evolutionism, though now outmoded, set the tone for early social theorists and anthropologists such as Harriet Martineau and Herbert Spencer. Modern academic sociology was later formally established in the 1890s by Émile Durkheim with a firm emphasis on practical and objective social research. Comte attempted to introduce a cohesive "religion of humanity" which, though largely unsuccessful, was influential in the development of various Secular Humanist organizations in the 19th century. He also created and defined the term "altruism".

Comte was born at Montpellier, Hérault, in southern France. After attending the Lycée Joffre and then the University of Montpellier, one of the oldest European universities, Comte was admitted to the École Polytechnique in Paris. The École Polytechnique was notable for its adherence to the French ideals of republicanism and progress. The École closed in 1816 for reorganization, however, causing Comte to leave and continue his studies at the medical school at Montpellier. When the École Polytechnique reopened, he did not request readmission.

Following his return to Montpellier, Comte soon came to see unbridgeable differences with his Catholic and Monarchist family and set off again for Paris, earning money by small jobs. In August 1817 he became a student and secretary to Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon, who brought Comte into contact with intellectual society and greatly influenced his thought thereon. It is during that time that Auguste Comte published his first essays in the various publications headed by Saint-Simon, L'Industrie, Le Politique, and L'Organisateur (Charles Dunoyer and Charles Comte's Le Censeur Européen), although he would not publish under his own name until 1819's "La séparation générale entre les opinions et les désirs" ("The general separation of opinions and desires"). In 1824, Comte left Saint-Simon, again because of unbridgeable differences. Comte published a Plan de travaux scientifiques nécessaires pour réorganiser la société (1822) (Plan of scientific studies necessary for the reorganization of society). But he failed to get an academic post. His day-to-day life depended on sponsors and financial help from friends. Debates rage as to how much Comte appropriated from the work of Saint-Simon.

Comte married Caroline Massin, but divorced in 1842. In 1826 he was taken to a mental health hospital, but left without being cured – only stabilized by French alienist Equirol – so that he could work again on his plan (he would later attempt suicide in 1827 by jumping off the Pont des Arts). In the time between this and their divorce, he published the six volumes of his Cours. Comte developed a close friendship with John Stuart Mill. From 1844, Comte was involved with Clotilde de Vaux, a relationship that remained platonic. After her death in 1846 this love became quasi-religious, and Comte, working closely with Mill (who was refining his own such system) developed a new "religion of humanity". John Kells Ingram, an adherent of Comte, visited him in 1855 in Paris.

He published four volumes of Système de politique positive (1851 – 1854). His final work, the first volume of "La Synthèse Subjective" ("The Subjective Synthesis"), was published in 1856.

Comte died in Paris on 5 September 1857 from stomach cancer and was buried in the famous Cimetière du Père Lachaise,

surrounded by cenotaphs in memory of his mother, Rosalie Boyer, and of

Caroline de Vaux. His apartment from 1841 - 1857 is now conserved as the Maison d'Auguste Comte and is located 10 rue Monsieur-le-Prince, in Paris' 6th arrondissement.

Comte first described the epistemological perspective of positivism in The Course in Positive Philosophy, a series of texts published between 1830 and 1842. These texts were followed by the 1848 work, A General View of Positivism (published in English in 1865). The first three volumes of the Course dealt chiefly with the physical sciences already in existence (mathematics, astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology), whereas the latter two emphasised the inevitable coming of social science. Observing the circular dependence of theory and observation in science, and classifying the sciences in this way, Comte may be regarded as the first philosopher of science in the modern sense of the term. For him, the physical sciences had necessarily to arrive first, before humanity could adequately channel its efforts into the most challenging and complex "Queen science" of human society itself. His View of Positivism would therefore set out to define, in more detail, the empirical goals of sociological method.

Comte offered an account of social evolution,

proposing that society undergoes three phases in its quest for the

truth according to a general 'law of three stages'. The idea bears some

similarity to Marx's view that human society would progress toward a communist peak. This is perhaps unsurprising as both were profoundly influenced by the early Utopian socialist, Henri de Saint-Simon,

who was at one time Comte's teacher and mentor. Both Comte and Marx

intended to develop, scientifically, a new secular ideology in the wake

of European secularisation.

Comte's stages were (1) the theological, (2) the metaphysical, and (3) the positive. The Theological phase was seen from the perspective of 19th century France as preceding the Enlightenment, in which man's place in society and society's restrictions upon man were referenced to God. Man blindly believed in whatever he was taught by his ancestors. He believed in a supernatural power. Fetishism played a significant role during this time. By the "Metaphysical" phase, he referred not to the Metaphysics of Aristotle or other ancient Greek philosophers. Rather, the idea was rooted in the problems of French society subsequent to the revolution of 1789. This Metaphysical phase involved the justification of universal rights as being on a vauntedly higher plane than the authority of any human ruler to countermand, although said rights were not referenced to the sacred beyond mere metaphor. This stage is known as the stage of investigation, because people started reasoning and questioning although no solid evidence was laid. The stage of investigation was the beginning of a world that questioned authority and religion. In the Scientific phase, which came into being after the failure of the revolution and of Napoleon, people could find solutions to social problems and bring them into force despite the proclamations of human rights or prophecy of the will of God. Science started to answer questions in full stretch. In this regard he was similar to Karl Marx and Jeremy Bentham. For its time, this idea of a Scientific phase was considered up-to-date, although from a later standpoint it is too derivative of classical physics and academic history. Comte's law of three stages was one of the first theories of social evolutionism.

The other universal law he called the "encyclopedic law." By combining these laws, Comte developed a systematic and hierarchical classification of all sciences, including inorganic physics (astronomy, earth science and chemistry) and organic physics (biology and, for the first time, physique sociale, later renamed sociologie). Independently from Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès's introduction of the term in 1780, Comte re-invented "sociologie," and introduced the term as a neologism, in 1838. Comte had earlier used the term "social physics," but that term had been appropriated by others, notably Adolphe Quetelet.

"The most important thing to determine was the natural order in which the sciences stand — not how they can be made to stand, but how they must stand, irrespective of the wishes of any one.... This Comte accomplished by taking as the criterion of the position of each the degree of what he called "positivity," which is simply the degree to which the phenomena can be exactly determined. This, as may be readily seen, is also a measure of their relative complexity, since the exactness of a science is in inverse proportion to its complexity. The degree of exactness or positivity is, moreover, that to which it can be subjected to mathematical demonstration, and therefore mathematics, which is not itself a concrete science, is the general gauge by which the position of every science is to be determined. Generalizing thus, Comte found that there were five great groups of phenomena of equal classificatory value but of successively decreasing positivity. To these he gave the names astronomy, physics, chemistry, biology, and sociology."

– Lester F. Ward, The Outlines of Sociology (1898)

This idea of a special science — not the humanities, not metaphysics — for

the social was prominent in the 19th century and not unique to Comte.

It has recently been discovered that the term "sociology" - a term

considered coined by Comte - had already been introduced in 1780,

albeit with a different meaning, by the French essayist Emmanuel Joseph Sieyès (1748 – 1836). The

ambitious — many would say grandiose — way that Comte conceived of this

special science of the social, however, was unique. Comte saw this new

science, sociology, as the last and greatest of all sciences, one which

would include all other sciences and integrate and relate their

findings into a cohesive whole. It has to be pointed out, however, that

there was a seventh science, one even greater than sociology. Namely,

Comte considered "Anthropology, or true science of Man [to be] the last gradation in the Grand Hierarchy of Abstract Science."

Comte’s explanation of the Positive philosophy introduced the important relationship between theory, practice and human understanding of the world. On page 27 of the 1855 printing of Harriet Martineau’s translation of The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte, we see his observation that, “If it is true that every theory must be based upon observed facts, it is equally true that facts can not be observed without the guidance of some theories. Without such guidance, our facts would be desultory and fruitless; we could not retain them: for the most part we could not even perceive them."

Comte is generally regarded as the first Western sociologist (Ibn Khaldun having preceded him in North Africa by nearly four centuries). Comte's emphasis on the interconnectedness of social elements was a forerunner of modern functionalism. Nevertheless, as with many others of Comte's time, certain elements of his work are now viewed as eccentric and unscientific, and his grand vision of sociology as the centerpiece of all the sciences has not come to fruition.

His emphasis on a quantitative, mathematical basis for decision making remains with us today. It is a foundation of the modern notion of Positivism, modern quantitative statistical analysis, and business decision making. His description of the continuing cyclical relationship between theory and practice is seen in modern business systems of Total Quality Management and Continuous Quality Improvement where advocates describe a continuous cycle of theory and practice through the four part cycle of plan, do, check, and act. Despite his advocacy of quantitative analysis, Comte saw a limit in its ability to help explain social phenomena.

The early sociology of Herbert Spencer came about broadly as a reaction to Comte; writing after various developments in evolutionary biology, Spencer attempted (in vain) to reformulate the discipline in what we might now describe as socially Darwinistic terms. (Spencer was in actual fact a proponent of Lamarckism rather than Darwinism).

Comte's fame today owes in part to Emile Littré, who founded The Positivist Review in 1867. Debates continue to rage, however, as to how much Comte appropriated from the work of his mentor, Henri de Saint-Simon.

In later life, Comte developed a 'religion of humanity' for positivist societies in order to fulfil the cohesive function once held by traditional worship. In 1849, he proposed a calendar reform called the 'positivist calendar'. For close associate John Stuart Mill, it was possible to distinguish between a "good Comte" (the author of the Course in Positive Philosophy) and a "bad Comte" (the author of the secular religious system). The system was unsuccessful but met with the publication of Darwin's On the Origin of Species to influence the proliferation of various Secular Humanist organizations in the 19th century, especially through the work of secularists such as George Holyoake and Richard Congreve. Although Comte's English followers, including George Eliot and Harriet Martineau, for the most part rejected the full gloomy panoply of his system, they liked the idea of a religion of humanity and his injunction to "vivre pour altrui" ("live for others"), from which comes the word "altruism".