<Back to Index>

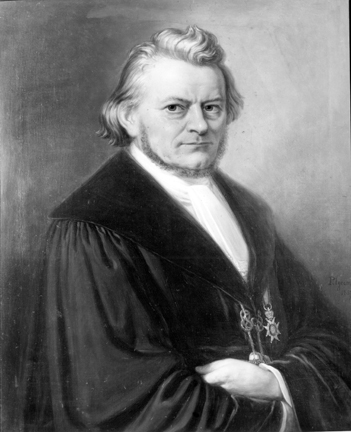

- Philosopher Immanuel Hermann Fichte, 1796

- Mezzo Soprano Pauline Viardot García, 1821

- Dictator of Afghanistan Mohammed Daoud Khan, 1909

PAGE SPONSOR

Immanuel Hermann von Fichte (18 July 1796 – 8 August 1879) was a German philosopher and son of Johann Gottlieb Fichte. In his philosophy, he was a theist and strongly opposed to the Hegelian School.

Fichte was born in Jena. He early devoted himself to philosophical studies, being attracted by the later views of his father, which he considered essentially theistic. He graduated from the University of Berlin in 1818. Soon after, he became a lecturer in philosophy there. He also attended the lectures of Hegel, but felt averse to what he deemed to be his pantheistic tendencies. As a result of semi-official suggestions, based on official disapproval of his supposedly liberal views, he decided, in 1822, to leave Berlin, and accepted a professorship at the gymnasium in Saarbrücken. In 1826 he went in the same capacity to Düsseldorf. In 1836 he became an extraordinary professor of philosophy at Bonn, and in 1840 full professor. Here he quickly became a successful and much admired lecturer. Dissatisfied with the reactionary tendencies of the Prussian Ministry of Education, he accepted a call to the chair of philosophy at the University of Tübingen in 1842 where he continued to give lectures on all philosophic subjects until his retirement in 1875 when he moved to Stuttgart. He died at Stuttgart on the 8th of August 1879.

In 1837, Fichte founded the Zeitschrift für Philosophie und speculative Theologie and edited from then on. In 1847, the name was changed to Zeitschrift für Philosophie und philosophische Kritik. Publication was suspended 1848 - 1852, after which Hermann Ulrici and Johann Ulrich Wirth joined him as editors. This journal served as an organ of Fichte's views, especially on the subject of the philosophy of religion, where he was in alliance with C.H. Weisse; but, whereas Weisse thought that the Hegelian structure

was sound in the main, and its imperfections might be mended, Fichte

held it to be defective, and spoke of it as a masterpiece of erroneous

consistency or consistent error. Fichte's general views on philosophy

seem to have changed considerably as he gained in years, and his

influence has been impaired by certain inconsistencies and an

appearance of eclecticism, which is strengthened by his predominantly

historical treatment of systems, his desire to include divergent

systems within his own, and his conciliatory tone. The

great aim of his speculations was to find a philosophic basis for the

personality of God, and for his theory on this subject he proposed the

term “concrete theism.” His philosophy attempts to reconcile monism (Hegel) and individualism (Herbart) by means of monadism (Leibniz). He attacks Hegelianism for its pantheism, lowering of human personality, and imperfect recognition of demands of the moral consciousness. God, he says, is to be regarded not as an absolute but

as an Infinite Person, whose desire it is that he should realize

himself in finite persons. These persons are objects of God's love, and

he arranges the world for their good. The direct connecting link

between God man is the genius, a higher spiritual individuality

existing fan by the side of his lower, earthly individuality. Fichte

advocates an ethical theism,

and his arguments might be turned to account by the apologist of

Christianity. In conception of finite personality he recurs to

something like monadism of Leibniz. His insistence on moral experience connected with his insistence on personality. One

of the tests which Fichte discriminates the value of previous systems

is adequateness with which they interpret moral experience. The same

reason that made him depreciate Hegel made him praise Krause (panentheism) and Schleiermacher,

and speak respectfully of English philosophy. It is characteristic of

Fichte's most excessive receptiveness that in his latest published work, Der neuere Spiritualismus (1878), he supports his position by arguments of a somewhat occult or theosophical cast, not unlike that adopted by F.W.H. Myers. The

regeneration of Christianity, according to Fichte, would consist in its

becoming the vital and organizing power in the state, instead of being

occupied solely, as heretofore, with the salvation of individuals.