<Back to Index>

- Economist Thorstein Bunde Veblen, 1857

- Poet Samuel Rogers, 1763

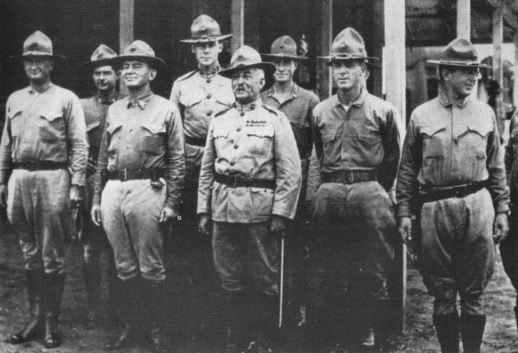

- Major General of the U.S. Marine Corps Smedley Darlington Butler, 1881

PAGE SPONSOR

Smedley Darlington Butler (July 30, 1881 – June 21, 1940), nicknamed "The Fighting Quaker" and "Old Gimlet Eye", was a Major General in the U.S. Marine Corps, and at the time of his death the most decorated Marine in U.S. history. During his 34 year career as a Marine, he participated in military actions in the Philippines, China, in Central America and the Caribbean during the Banana Wars, and France in World War I. By the end of his career he had received 16 medals, five of which were for heroism. He is one of 19 people to twice receive the Medal of Honor, one of three to be awarded both the Marine Corps Brevet Medal and the Medal of Honor, and the only person to be awarded the Brevet Medal and two Medals of Honor, all for separate actions.

In

addition to his military achievements, he served as the Director of

Public Safety in Philadelphia for two years and was an outspoken critic of U.S. military adventurism. In his 1935 book War is a Racket, he described the workings of the military - industrial complex and, after retiring from service, became a popular speaker at meetings organized by veterans, pacifists and church groups in the 1930s. In 1934 he was involved in a controversy known as the Business Plot when he told a congressional committee that a group of wealthy industrialists had approached him to lead a military coup to overthrow Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The individuals that were involved denied the existence of a plot, and

the media ridiculed the allegations. The final report of the committee

claimed that there was evidence that such a plot existed, but no

charges were ever filed. The opinion of most historians is that while

planning for a coup was not very advanced, wild schemes were discussed. Butler

continued his speaking engagements in an extended tour but in June 1940

checked himself into a naval hospital, dying a few weeks later from

what was believed to be cancer. He was buried at Oaklands Cemetery in West Chester, Pennsylvania; his home has been maintained as a memorial and contains memorabilia collected during his various careers. Smedley Butler was born July 30, 1881, in West Chester, Pennsylvania, the eldest of three sons. His parents Thomas Stalker Butler and Maud (Darlington) Butler were descended from local Quaker families.

His father was a lawyer, a judge and, for 31 years, a Congressman and chair of the House Naval Affairs Committee during the Harding and Coolidge administrations. His maternal grandfather was Smedley Darlington, a Republican Congressman from 1887 - 1891. Butler attended the West Chester Friends Graded High School, followed by The Haverford School, a secondary school popular with sons of upper class Philadelphia families. A Haverford athlete, he became captain of its baseball team and quarterback of its football team. Against

the wishes of his father, he left school 38 days before his

seventeenth birthday to enlist in the Marine Corps during the Spanish – American War. Regardless,

Haverford awarded him his high school diploma on June 6, 1898, before

the end of his final year; his transcript stated he completed the

Scientific Course "with Credit".

In the anti-Spanish war fever of 1898, Butler lied about his age to receive a direct commission as a Marine second lieutenant. He trained in Washington D.C. at the Marine Barracks on the corner of 8th and I Streets. In July 1898, he went to Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, arriving after the invasion and capture. His unit returned to the U.S. After a short break, he was assigned to the armored cruiser USS New York and deployed for four months. He came home to be mustered out of service in February 1899, but in April 1899, he accepted a commission as a first lieutenant in the Marine Corps. The Marines next sent him to the Manila, Philippines. On

garrison duty, with little to occupy him, he engaged in bouts of

drinking to alleviate the tedium. On one occasion he became drunk, and

was temporarily demoted from command after an unspecified incident in

his room. In October 1899, he saw his first combat action when leading 300 Marines to take the town of Noveleta, against Filipino rebels known as Insurrectos. In the initial moments of the engagement, the first sergeant in Butler's unit was wounded. Butler panicked, but regained his composure and led the Marines in pursuit of the enemy forces. By

noon the Marines had dispersed the rebels and taken the town. In the

fighting, one Marine was killed and ten were wounded. Another 50

Marines were incapacitated by the tropical Philippine heat. After the excitement of his first combat action, garrison duty again became routine. To pass the time, Butler had a very large Eagle, Globe, and Anchor tattoo that started at his throat and extended to his waist. He also met another Marine, Littleton Waller with whom he subsequently maintained a life long friendship. When Waller received command of a unit in Guam,

he was allowed to select five officers to take with him; he chose

Butler, but before they could depart, their orders were changed and

they were instead sent to China aboard the USS Solace. During the Boxer Rebellion, Butler was initially deployed at Tientsin. At the Battle of Tientsin on

July 13, 1900, he saw another officer fall with wounds and, while

climbing out of a trench to rescue him, Butler was himself shot in the

thigh. Another Marine noticed that Butler had been wounded and helped

him get to safety; in doing so that Marine was shot. Despite his

injury, Butler assisted the first officer to the rear. Four enlisted men received

the Medal of Honor in the battle. His commanding officer, Major

Littleton W.T. Waller, personally commended him in his report and

recommended that "for such reward as you may deem proper the following

officers: Lieutenant Smedley D. Butler, for the admirable control of

his men in all the fights of the week, for saving a wounded man at the

risk of his own life, and under a very severe fire." Although officers

were not then eligible to receive the Medal of Honor, Butler received a

promotion to captain by brevet while recovering in the hospital, two weeks before his nineteenth birthday. Butler was shot in the chest, at Battle of San Tan Pating, the bullet reportedly clipping part of Central America out of his tattoo. Because of his experience in China, he was eligible for the Marine Corps Brevet Medal when it was created in 1921; he was one of only 20 Marines to receive the medal. His citation reads: Between

the Honduran campaign and his next assignment, he returned to

Philadelphia. He married Ethel Conway Peters of Philadelphia in Bay Head, New Jersey, on June 30, 1905. His best man at the wedding was his former commanding officer in China, Lieutenant Colonel Littleton W.T. Waller. The couple would have three children: a daughter, Ethel Peters Butler, and two sons, Smedley Darlington, Jr. and Thomas Richard. After the Honduras campaign, Butler was assigned to garrison duty in the Philippines, where he once launched a resupply mission across the stormy waters of Subic Bay after

his isolated outpost ran out of rations. He was diagnosed as having a

nervous breakdown in 1908, and received nine months sick leave for

which he returned home. He found work as a coal miner in West Virginia, but did not find mining to his taste, and returned to active duty in the Marine Corps.

From 1909 to 1912, he served in Nicaragua, enforcing U.S. policy, and once again led his battalion to the relief of a rebel besieged city, this time Granada, and again, with a 104 degree fever. In December 1909, he commanded the 3d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, on the Isthmus of Panama.

On August 11, 1912, he was temporarily detached to command an

expeditionary battalion with which he participated in the bombardment,

assault and capture of Coyotepe Hill, Nicaragua, in October 1912. He remained in Nicaragua until November 1912, when he rejoined the Marines of 3d Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, at Camp Elliott, Panama. Butler and his family were living in Panama in January 1914 when he was ordered to report as the Marine officer of a battleship squadron massing off the coast of Mexico, near Veracruz,

to monitor a revolutionary movement. He did not like leaving his family

and the home they had established in Panama and he intended to request

orders home as soon as he determined he was not needed. On March 1, 1914, Butler and Admiral Frank Fletcher went ashore in Veracruz and made their way to Jalapa, Mexico, and

back. A purpose of the trip was to allow Butler and Fletcher to discuss

the details of a future expedition into Mexico. Fletcher's plan

required Butler to make his way into the country and develop a more

detailed invasion plan while inside its borders. It was a spy mission

and Butler was enthusiastic to get started. When Admiral Fletcher

explained the plan to the commanders in Washington, D.C., they agreed

to it. Butler was given the go-ahead. He entered Mexico and made his

way to the U.S. Consulate in Mexico City,

posing as a railroad official named "Mr. Johnson". He and the chief

railroad inspector scoured the city, claiming to be searching for a

lost railroad employee; there was no lost employee, in fact the

employee they claimed was lost never existed. The ruse gave Butler

access to various areas of the city. In the process of the so-called

search, they located weapons in use by the Mexican army, and determined

the sizes of units and states of readiness. They updated maps and

verified the railroad lines for use in an impending US invasion. On

March 7, 1914, he returned to Veracruz with the information he had

gathered and presented it to his commanders. The invasion plan was eventually scrapped when authorities loyal to Victoriano Huerta detained a small American naval landing party in Tampico, Mexico, which became known as the Tampico Affair. When President Woodrow Wilson discovered

that an arms shipment was about to arrive in Mexico, he sent a

contingent of Marines and sailors to Veracruz to intercept it on April

21, 1914. Over the next few days, street fighting and sniper fire posed

a threat to Butler's force, but a door-to-door search routed out most

of the resistance. By April 26, the landing force of 5,800 Marines and

sailors secured the city, which they held for the next six months. By

the end of the conflict, the Americans reported 17 dead and 63 wounded

and the Mexican forces had 126 dead and 195 wounded. After the actions

at Veracruz, the United States decided to minimize the bloodshed and

changed their plans from a full invasion of Mexico to simply maintaining the city of Veracruz. For his actions on April 22, Butler was awarded his first Medal of Honor. The citation reads: After

the occupation of Veracruz, many military personnel received the Medal

of Honor, an unusually high number that diminished somewhat the

prestige of the award. The Army presented one, nine went to Marines and

46 were bestowed upon Navy personnel. During World War I, Butler, then a major,

attempted to return his Medal, explaining he had done nothing to

deserve it. The medal was returned with orders to keep it and to wear

it as well. In 1915, rebel Haitians known as Cacos killed the Haitian dictator Vilbrun Guillaume Sam. In response, the United States ordered the USS Connecticut to Haiti with Major Butler and a group of Marines on board. On October 24, 1915, 400 Cacos ambushed Butler's patrol of 44 mounted Marines when they approached Fort Dipitie.

The Marines maintained their perimeter throughout the night. The next

morning, they charged the much larger enemy force from three

directions. The startled Haitians fled, thinking that the Marines had a

much larger force. By mid November 1915, most of the Cacos had been captured or killed and the insurgency generally suppressed, except for a small force of 200 Cacos at Fort Rivière, an old French built stronghold deep in the country. Fort Rivière sat atop Montagne Noire,

with its front reachable only by a steep, rocky slope; the other three

sides fell away so sharply that an approach from those directions was

considered to be impossible. Some Marine officers argued that it should

be assaulted by a regiment supported by artillery, but Butler convinced his colonel to allow him to attack with just four companies of 24 men each, plus two machine gun detachments. For the operation, Butler was given only three companies of Marines and some sailors from the USS Connecticut.

They encircled the fort, and gradually closed in on it. Butler reached

the fort from the southern side with the 15th Company and found a small

opening in the wall. The Marines entered through the opening and

engaged the Cacos in

hand-to-hand combat. He and the Marines took the rebel stronghold on

November 17, 1915, an action for which he received his second Medal of

Honor, as well as the Haitian Medal of Honor. Only one Marine was injured in the assault when he was struck by a rock and lost two teeth. Butler's exploits impressed then Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt, who recommended the award based upon Butler's performance during the engagement in which all 200 Cacos were killed. Once the medal was approved and presented in 1917, Butler achieved the distinction, shared with Dan Daly, of being the only Marines to receive the Medal of Honor twice for separate actions. The citation reads: Subsequently, as the initial organizer and commanding officer of the Haitian Gendarmerie,

the native police force, Butler established a record as a capable

administrator. Under his supervision, social order, administered by the

dictatorship, was largely restored and many vital public works projects

were successfully completed. He recalled later that, during his time in Haiti, he and his troops "hunted the Cacos like pigs." During World War I, to his disappointment, Butler was not assigned to a combat command on the Western Front. He made several requests for a posting in France, writing letters to his personal friend, Major General Wendell Cushing Neville, who was at the time assistant to the then Commandant of the Marine Corps, Lieutenant General John A. Lejeune. While Butler's superiors considered him brave and brilliant, they described him as "unreliable." In October 1918, he was promoted to the rank of brigadier general at the age of 37 and placed in command of Camp Pontanezen at Brest, France, a debarkation depot that funneled troops of the American Expeditionary Force to the battlefields. The camp had been plagued by horribly unsanitary, overcrowded and disorganized conditions. U.S. Secretary of War Newton Baker sent novelist Mary Roberts Rinehart to

report on the camp. She later described how Butler tackled the

sanitation issues. Butler began by solving the mud problem: "[T]he

ground under the tents was nothing but mud, [so] he had raided the

wharf at Brest of the duckboards no

longer needed for the trenches, carted the first one himself up that

four mile hill to the camp, and thus provided something in the way of

protection for the men to sleep on." General John J. Pershing authorized

a duckboard shoulder patch for the units. This earned Butler another

nickname, "Old Duckboard." For his exemplary service he was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal of both the United States Army and Navy and the French Order of the Black Star. The citation for the Army Distinguished Service Medal states: The citation for the Navy Distinguished Service Medal states: Following the war, he became Commanding General of the Marine Barracks at Marine Corps Base Quantico, Virginia.

At Quantico, he transformed the wartime training camp into a permanent

Marine post. During a training exercise in western Virginia in 1921, he

was told by a local farmer that Stonewall Jackson's arm was buried nearby, to which he replied, "Bosh! I will take a squad of Marines and dig up that spot to prove you wrong!" Butler

found the arm in a box. He later replaced the wooden box with a metal

one, and reburied the arm. He left a plaque on the granite monument

marking the burial place of Jackson's arm; the plaque is no longer on

the marker but can be viewed at the Chancellorsville Battlefield

visitor's center. From 1927 to 1929, Butler was commander of the Marine Expeditionary Force in China and,

while there, cleverly parlayed his influence among various generals and

warlords to the protection of U.S. interests, ultimately winning the

public acclaim of contending Chinese leaders. When Butler returned to

the United States in 1929 he was promoted to major general,

becoming, at age 48, the youngest major general of the Marine Corps. He

directed the Quantico camp's growth until it became the "showplace" of

the Corps. Butler won national attention by taking thousands of his men on long field marches, many of which he led from the front, to Gettysburg and other Civil Warbattle sites, where they conducted large scale re-enactments before crowds of distinguished spectators. In 1931, he publicly recounted gossip about Benito Mussolini in which the dictator allegedly struck a child with his automobile in a hit-and-run accident. The Italian government protested and President Hoover, who strongly disliked Butler, forced Secretary of the Navy Charles Francis Adams III to court-martial him.

Butler became the first general officer to be placed under arrest since

the Civil War. He apologized to Secretary Adams and the court martial

was canceled with only a reprimand. At the urging of Butler's father, in 1924, the newly elected mayor of Philadelphia W. Freeland Kendrick asked

him to leave the Marines to become the Director of Public Safety, the

official in charge of running the city's police and fire departments. Philadelphia's municipal government was notoriously corrupt and Butler initially refused. Kendrick asked President Calvin Coolidge to

intervene. Coolidge contacted Butler and authorized him to take the

necessary leave from the Corps. At the request of the President, Butler

served in the post from January 1924 until December 1925. He

began his new job by assembling all 4,000 of the city police into the

Metropolitan Opera House in shifts to introduce himself and inform them

that things would change while he was in charge. He replaced corrupt

police officers and, in some cases, switched entire units from one part

of the city to another, undermining local protection rackets and

profiteering. Within 48 hours of taking over, Butler organized raids on more than 900 speakeasies,

ordering them padlocked and, in many cases, destroyed. In addition to

raiding the speakeasies, he also attempted to eliminate other illegal

activities: bootlegging, prostitution, gambling and police corruption.

More zealous than he was political, he ordered crackdowns on the social

elite's favorite hangouts, such as the Ritz - Carlton and the Union League, as well as on drinking establishments that served the working class. Although

he was effective in reducing crime and police corruption, he was a

controversial leader. In one instance he made a statement that he would

promote the first officer to kill a bandit and stated, "I don't believe

there is a single bandit notch on a policeman's guns [sic] in this city, go out and get some." Although many of the local citizens and police felt that the raids were just a show, the raids continued for several weeks. He

implemented programs to improve city safety and security. He

established policies and guidelines of administration, and developed a

Philadelphia police uniform that resembled that of the Marine Corps. Other changes included military style checkpoints into the city, bandit chasing squads armed with sawed-off shotguns, and armored police cars. The

press began reporting on the good and the bad aspects of Butler's

personal war on crime. The reports praised the new uniforms, the new

programs and the reductions in crime but they also reflected the

public's negative opinion of their new Public Safety director. Many

felt that he was being too aggressive in his tactics and resented the

reductions in their civil rights, such as the stopping of citizens at

the city checkpoints. Butler frequently swore in his radio addresses,

causing many citizens to suggest his behavior, particularly his

language, was inappropriate for someone of his rank and stature. Some

even suggested Butler acted like a military dictator, even claiming

that he inappropriately used active duty Marines in some of his raids. Major

R.A. Haynes, the federal Prohibition commissioner, visited the city in

1924, six months after Butler was appointed. He announced that "great

progress" had been made in the city and attributed that success to Butler. Eventually

Butler's leadership style and the directness of actions undermined his

support within the community. His departure seemed imminent. Mayor

Kendrick reported to the press, "I had the guts to bring General Butler

to Philadelphia and I have the guts to fire him." Feeling that his duties in Philadelphia were coming to an end, Butler contacted

General Lejeune to prepare for his return to the Marine Corps. Not all

of the city felt he was doing a bad job though and when the news

started to break that he would be leaving, people began to gather at the Academy of Music.

A group of 4,000 supporters assembled and negotiated a truce between

him and the mayor to keep him in Philadelphia for a while longer, and

the President authorized a one year extension for him. His

second year focused on executing arrest warrants, cracking down on

crooked police and enforcing prohibition. On January 1, 1926, his leave

from the Marine Corps ended and the President declined a request for a

third extension. Butler received orders to report to San Diego and he prepared his family and his belongings for the new assignment. In

light of his pending departure, Butler began to defy the Mayor and

other key city officials. On the eve of his departure, he had an

article printed in the paper stating his intention to stay and "finish

the job". The mayor was surprised and furious when he read the press release the next morning and demanded his resignation. After

almost two years in office, Butler resigned under pressure, stating

later that "cleaning up Philadelphia was worse than any battle I was

ever in."

Even

before retiring from the Corps, Butler began developing his post-Corps

career. In May 1931, he took part in a commission established by Oregon Governor Julius L. Meier. The commission laid the foundations for the Oregon State Police. He

began lecturing at events and conferences and after his retirement from

the Marines in 1931, he took this up full time. He donated much of his

earnings from his lucrative lecture circuits to the Philadelphia

unemployment relief. He toured the western United States, making 60

speeches before returning for his daughter's marriage to Marine aviator

Lieutenant John Wehle. Her wedding was the only time that he wore his

dress blue uniform after he left the Marines. He became widely known for his outspoken lectures against war profiteering, U.S. military adventurism, and what he viewed as nascent fascism in the United States. In December 1933, Butler toured the country with James E. Van Zandt to recruit members for the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW). He described their effort as "trying to educate the soldiers out of the sucker class." In his speeches he denounced the Economy Act of

1933, called on veterans to organize politically to win their benefits,

and condemned the FDR administration for its ties to big business. The

VFW reprinted one of his speeches with the title "You Got to Get Mad"

in its magazine Foreign Service. He said: "I believe in... taking Wall St. by the throat and shaking it up." He believed the American Legion was

controlled by banking interests. On December 8, 1933, explaining why he

believed veterans' interests were better served by the VFW than the

American Legion, he said: "I said I have never known one leader of the

American Legion who had never sold them out – and I mean it." In addition to his speeches to pacifist groups, he served from 1935 to 1937 as a spokesman for the American League Against War and Fascism. In 1935 he wrote the exposé War Is a Racket, a trenchant condemnation of the profit motive

behind warfare. His views on the subject are summarized in the

following passage from a 1935 issue of the socialist magazine Common Sense: I

spent 33 years and four months in active military service and during

that period I spent most of my time as a high class thug for Big

Business, for Wall Street and the bankers. In short, I was a racketeer,

a gangster for capitalism. I helped make Mexico and especially Tampico

safe for American oil interests in 1914. I helped make Haiti and Cuba a

decent place for the National City Bank boys to collect revenues in. I

helped in the raping of half a dozen Central American republics for the

benefit of Wall Street. I helped purify Nicaragua for the International

Banking House of Brown Brothers in 1902 – 1912. I brought light to the

Dominican Republic for the American sugar interests in 1916. I helped

make Honduras right for the American fruit companies in 1903. In China

in 1927 I helped see to it that Standard Oil went on its way

unmolested. Looking back on it, I might have given Al Capone a few

hints. The best he could do was to operate his racket in three

districts. I operated on three continents. In November 1934, Butler alleged the existence of a political conspiracy of Wall Street interests to overthrow President Roosevelt, a series of allegations that came to be known in the media as the Business Plot. A special committee of the House of Representatives headed by Representatives John W. McCormack of Massachusetts and Samuel Dickstein of New York, who was later revealed to have been a paid agent of the NKVD, heard his testimony in secret. The McCormack - Dickstein committee was a precursor to the House Committee on Un-American Activities. In

November 1934, Butler told the committee that a group of businessmen,

claiming to be backed by a private army of 500,000 ex-soldiers and

others, intended to establish a fascist dictatorship. Butler had been

asked to lead it, he said, by Gerald P. MacGuire, a bond salesman with

Grayson M–P Murphy & Co. The New York Times reported that Butler had told friends that General Hugh S. Johnson, a former official with the National Recovery Administration, was to be installed as dictator. Butler said MacGuire had told him the attempted coup was

backed by three million dollars, and that the 500,000 men were probably

to be assembled in Washington, D.C., the following year. All the parties

alleged to be involved, including Johnson, said there was no truth in

the story, calling it a joke and a fantasy. In

its report, the committee stated that it was unable to confirm Butler's

statements other than the proposal from MacGuire, which it considered more or less confirmed by MacGuire's European reports. No prosecutions or further investigations followed, and historians have questioned whether or not a coup was actually close to execution, although most agree that some sort of "wild scheme" was contemplated and discussed. The news media initially dismissed the plot, with a New York Times editorial characterizing it as a "gigantic hoax". When the committee's final report was released, the Times said

the committee "purported to report that a two month investigation had

convinced it that General Butler's story of a Fascist march on

Washington was alarmingly true" and "... also alleged that definite

proof had been found that the much publicized Fascist march on

Washington, which was to have been led by Major. Gen. Smedley D.

Butler, retired, according to testimony at a hearing, was actually

contemplated". The

McCormack-Dickstein Committee confirmed some of Butler's accusations in

its final report. "In the last few weeks of the committee's official

life it received evidence showing that certain persons had made an

attempt to establish a fascist organization in this country... There is

no question that these attempts were discussed, were planned, and might

have been placed in execution when and if the financial backers deemed

it expedient." In

June 1940, Butler checked himself into the hospital after becoming sick

a few weeks earlier. His doctor described his illness as an incurable

condition of the upper gastro-intestinal tract that was probably

cancer. His family remained by his side, even bringing his new car so

he could see it from the window. He never had a chance to drive it. On

June 21, 1940, Smedley Butler died in the Naval Hospital in

Philadelphia. The

funeral was held at his home, attended by friends and family as well as

several politicians, members of the Philadelphia police force and

officers of the Marine Corps. He was buried at Oaklands Cemetery in West Chester, Pennsylvania. Since

his death in 1940, his family has maintained his home as it was when he

died, including a large amount of memorabilia he had collected

throughout his varied career.

In 1903, Butler was stationed in the Caribbean on Culebra Island.

Upon rumors of a Honduran revolt, the United States government ordered

the Marines and a supporting naval detachment to sail to Honduras,

1,500 miles (2,414 km) to the west, to defend the U.S. Consulate in Honduras. Using a converted banana boat renamed the Panther, Butler and several hundred Marines landed at the port town of Puerto Cortés.

In a letter home, he described the action: They were "prepared to land

and shoot everybody and everything that was breaking the peace", but instead found a quiet town. The Marines re-boarded the Panther and continued up the coast line looking for rebels at several towns, but found none. When they arrived at Trujillo, however, they heard gunfire, and came upon a battle in progress that had been waged for 55 hours between the Bonillistas and

the Honduran soldiers at a local fort. At the sight of the Marines, the

fighting ceased and Butler led a detachment of Marines to the American

consulate, where he found the consul, wrapped in an American flag,

hiding among the floor beams. As soon as the Marines left the area with

the shaken consul, the battle resumed and the Bonillistas soon

controlled the government. During

this expedition Butler earned the first of his nicknames, "Old Gimlet

Eye". It was attributed to his feverish, bloodshot eyes — he was

suffering from some unnamed tropic fever at the time — which enhanced his

penetrating and bellicose stare.

In

the old Marine tradition, when a Commandant retired or died, it was

customary for the senior Marine Corps general to assume the position of

Commandant while a new one was chosen. However, when Marine Corps

commandant Major General Wendell C. Neville died July 8, 1930, Butler, at that time the senior major general in the Corps, was not appointed. Although he had significant support from many inside and outside the Corps, including John Lejeune and Josephus Daniels, two other Marine Corps generals were seriously considered for the post, Ben H. Fuller and John H. Russell. General Lejeune and others petitioned President Hoover, garnered support in the Senate and flooded then Secretary of the Navy Charles Adams's desk with more than 2,500 letters of support. With

the recent death of his influential father, however, Butler had lost

much of his protection from his civilian superiors. The outspokenness

that characterized his run-ins with the Mayor of Philadelphia, the

"unreliability" mentioned by his superiors when opposing a posting to

the Western Front, and his comments about Benito Mussolini resurfaced.

Going against Marine Corps tradition, the position of Commandant went

to Major General Ben H. Fuller and, at his own request, Butler retired from active duty on October 1, 1931.

He announced his candidacy for the U.S. Senate in the Republican primary in Pennsylvania in March 1932 as a proponent of the prohibition, known as a "dry". He allied with Gifford Pinchot, but they were defeated by Senator James J. Davis. During

his Senate campaign, Butler spoke out forcefully about the veterans

bonus. Veterans of World War I, many of whom had been out of work since

the beginning of the Great Depression, sought immediate cash payment of Service Certificates granted to them eight years earlier via the World War Adjusted Compensation Act of

1924. Each Service Certificate, issued to a qualified veteran soldier,

bore a face value equal to the soldier's promised payment, plus compound interest.

The problem was that the certificates (like bonds), matured 20 years

from the date of original issuance, thus, under extant law, the Service

Certificates could not be redeemed until 1945. In June 1932,

approximately 43,000 marchers — 17,000 of which were World War I

veterans, their families, and affiliated groups, who protested in

Washington, D.C., in spring and summer of 1932. The Bonus Expeditionary Force, also known as the "Bonus Army",

marched on Washington to advocate the passage of the "soldier's bonus"

for service during World War I. After Congress adjourned, bonus

marchers remained in the city and became unruly. On July 28, 1932, two

bonus marchers were shot by police, causing the entire mob to become

hostile and riotous. The FBI, then known as the United States Bureau of

Investigation, checked its fingerprint records to obtain the police

records of individuals who had been arrested during the riots or who

had participated in the bonus march. The

veterans made camp in the Anacostia flats while they awaited the

congressional decision on whether or not to pay the bonus. The motion,

known as the Patnum bill, was decisively defeated, but the veterans

stayed in their camp. Butler arrived with his young son Thomas, in mid

July the day before the official eviction by the Hoover administration.

He walked through the camp and spoke to the veterans; he told them that

they were fine soldiers and they had a right to lobby Congress just as

much as any corporation. He and his son spent the night and ate with

the men, and in the morning Butler gave a speech to the camping

veterans. He instructed them to keep their sense of humor and cautioned

them not to do anything that would cost public sympathy. On July 28, army cavalry units led by General Douglas MacArthur dispersed

the Bonus Army by riding through it and using gas. During the conflict

several veterans were killed or injured and Butler declared himself a

"Hoover-for-Ex-President-Republican".