<Back to Index>

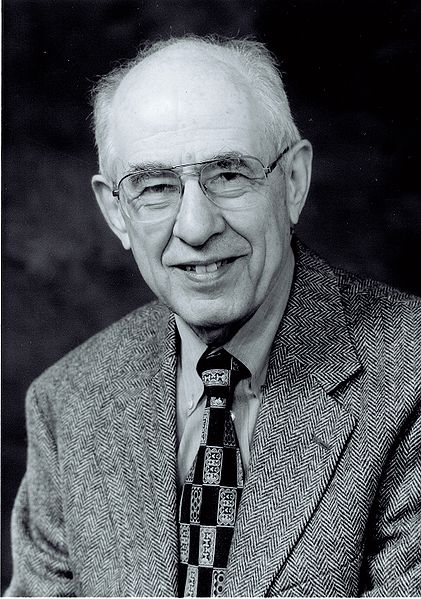

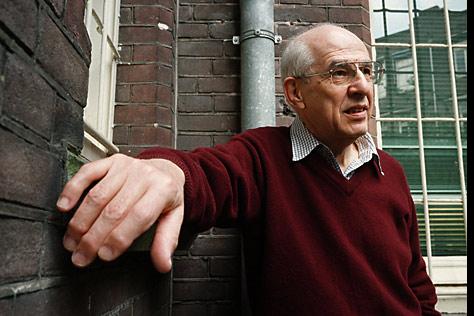

- Philosopher Hilary Whitehall Putnam, 1926

- Composer Amélie Julie Candeille, 1767

- Prime Minister of Spain José Canalejas y Méndez, 1854

PAGE SPONSOR

Hilary Whitehall Putnam (b. July 31, 1926) is an American philosopher who has been a central figure in analytic philosophy since the 1960s, especially in philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, and philosophy of science. He is known for his willingness to apply an equal degree of scrutiny to his own philosophical positions as to those of others, subjecting each position to rigorous analysis until he exposes its flaws. As a result, he has acquired a reputation for frequently changing his own position. Putnam is currently Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University.

In philosophy of mind, Putnam is known for his argument against the type - identity of mental and physical states based on his hypothesis of the multiple realizability of the mental, and for the concept of functionalism, an influential theory regarding the mind - body problem. In philosophy of language, along with Saul Kripke and others, he developed the causal theory of reference, and formulated an original theory of meaning, inventing the notion of semantic externalism based on a famous thought experiment called Twin Earth. In philosophy of mathematics, he and his mentor W.V. Quine developed the "Quine - Putnam indispensability thesis," an argument for the reality of mathematical entities, later espousing the view that mathematics is not purely logical, but "quasi - empirical". In the field of epistemology, he is known for his critique of the well known "brain in a vat" thought experiment. This thought experiment appears to provide a powerful argument for epistemological skepticism, but Putnam challenges its coherence. In metaphysics, he originally espoused a position called metaphysical realism, but eventually became one of its most outspoken critics, first adopting a view he called "internal realism", which he later abandoned in favor of a pragmatist inspired direct realism. Putnam's "direct realism" aims to return the study of metaphysics to

the way people actually experience the world, rejecting the idea of mental representations, sense data, and other intermediaries between mind and world. In his later work, Putnam has become increasingly interested in American pragmatism, Jewish philosophy, and ethics, thus engaging with a wider array of philosophical traditions. He has also displayed an interest in metaphilosophy, seeking to "renew philosophy" from what he identifies as narrow and inflated concerns. Outside philosophy, Putnam has contributed to mathematics and computer science. Together with Martin Davis he developed the Davis – Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem and he helped demonstrate the unsolvability of Hilbert's tenth problem. He has been at times a politically controversial figure, especially for his involvement with the Progressive Labor Party in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Putnam was born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1926. His father, Samuel Putnam, was a scholar of Romance languages, columnist and translator who wrote for the Daily Worker, a publication of the American Communist Party from 1936 to 1946 (when he became disillusioned with communism). As a result of his father's commitment to communism, Putnam had a secular upbringing, although his mother, Riva, was Jewish. The family lived in France until 1934, when they returned to the United States, settling in Philadelphia. Putnam attended Central High School; there he met Noam Chomsky, who was a year behind him. The two have been friends — and often intellectual opponents — ever since. Putnam studied mathematics and philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania, receiving his BA (undergraduate degree) and becoming a member of the Philomathean Society, the oldest U.S. literary society. He went on to do graduate work in philosophy at Harvard University, and later at UCLA's Philosophy Department, where he received his Ph.D. in

1951 for a dissertation entitled "The Meaning of the Concept of

Probability in Application to Finite Sequences". Putnam's teacher Hans Reichenbach (his dissertation supervisor) was a leading figure in logical positivism,

the dominant school of philosophy of the day; one of Putnam's most

consistent positions has been his rejection of logical positivism as

self-defeating. After briefly teaching at Northwestern, Princeton, and MIT, he moved to Harvard in 1965 with his wife, Ruth Anna Jacobs, who also took a teaching position in philosophy at MIT. Hilary and Ruth Anna were married in 1962. Ruth Anna Jacobs, descendant of an old German scholarship family in Gotha (her ancestor was the German classical scholar Christian Friedrich Wilhelm Jacobs), was born in Berlin, Germany, in 1927 to anti-Nazi political activist parents and, like Putnam himself, she was raised an atheist. The Putnams, rebelling against the anti-Semitism that they had experienced during their youth, decided to establish a traditional Jewish home for their children. Since they had no experience with the rituals of Judaism, they sought out invitations to other Jews' homes for Seder.

They had "no idea how to do it [themselves]", in the words of Ruth

Anna. They therefore began to study Jewish ritual and Hebrew, and

became more Jewishly interested, identified, and active. In 1994,

Hilary Putnam celebrated a belated Bar Mitzvah service. His wife had a Bat Mitzvah service four years later. Hilary was a popular teacher at Harvard. In keeping with the family tradition, he was politically active. In the 1960s and early 1970s, he was an active supporter of civil rights causes and an opponent of American military intervention in Vietnam. In

1963, he organized one of the first faculty and student committees at

MIT against the war. Putnam was disturbed when he learned from reading

the reports of David Halberstam that the U.S. was "defending" South

Vietnamese peasants from the Vietcong by poisoning their rice crops. After moving to Harvard in 1965, he organized campus protests and began teaching courses on Marxism. Hilary became an official faculty advisor to the Students for a Democratic Society and, in 1968, became a member of the Progressive Labor Party (PLP). After 1968, his political activities were centered on the PLP. The

Harvard administration considered these activities disruptive and

attempted to censure Putnam, but two other faculty members criticized

the procedures. Putnam permanently severed his ties with the PLP in 1972. In 1997, at a meeting of former draft resistance activists at Arlington Street Church in Boston,

Putnam described his involvement with the PLP as a mistake. He said

that he had been impressed at first with PLP's commitment to

alliance building, and its willingness to attempt to organize from

within the armed forces. In 1976, he was elected President of the American Philosophical Association.

The following year, he was selected as Walter Beverly Pearson Professor

of Mathematical Logic, in recognition of his contributions to philosophy of logic and mathematics. While

breaking with his radical past, Putnam has never abandoned his belief

that academics have a particular social and ethical responsibility

toward society. He has continued to be forthright and progressive in

his political views, as expressed in the articles "How Not to Solve

Ethical Problems" (1983) and "Education for Democracy" (1993). Professor Hilary W. Putnam is a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy. He retired from teaching in June 2000, but, as of 2009, he still gives a seminar almost yearly at Tel Aviv University.

He is the Cogan University Professor Emeritus at Harvard University. He

is also a founding patron of the small liberal arts college Ralston College. His corpus includes five volumes of collected works, seven books, and

more than 200 articles. Putnam's renewed interest in Judaism has

inspired him to publish several recent books and essays on the topic. With his wife, he has co-authored several books and essays on the late 19th century American pragmatist movement. Putnam has contributed to scientific fields not directly related to his work in philosophy. As a mathematician, Putnam contributed to the resolution of Hilbert's tenth problem in mathematics. Yuri Matiyasevich had formulated a theorem involving the use of Fibonacci numbers in 1970, which was designed to answer the question of whether there is a general algorithm that can decide whether a given system of Diophantine equations (polynomials with integer coefficients) has a solution among the integers. Putnam, working with Martin Davis and Julia Robinson,

demonstrated that Matiyasevich's theorem was sufficient to prove that

no such general algorithm can exist. It was therefore shown that David Hilbert's famous tenth problem has no solution. In computability theory, Putnam investigated the structure of the ramified analytical hierarchy, its connection with the constructible hierarchy and its Turing degrees. He showed that there exist many levels of the constructible hierarchy which do not add any subsets of the integers and later, with his student George Boolos, that the first such "non-index" is the ordinal β0 of ramified analysis (this is the smallest β such that Lβ is a model of full second-order comprehension), and also, together with a separate paper with Richard Boyd (another of Putnam's students) and Gustav Hensel, how the Davis – Mostowski – Kleene hyperarithmetical hierarchy of arithmetical degrees can be naturally extended up to β0. In computer science, Putnam is known for the Davis - Putnam algorithm for the Boolean satisfiability problem (SAT), developed with Martin Davis in 1960. The algorithm finds if there is a set of true or false values that satisfies a given Boolean expression so that the entire expression becomes true. In 1962, they further refined the algorithm with the help of George Logemann and Donald W. Loveland. It became known as the DPLL algorithm. This algorithm is efficient and still forms the basis of most complete SAT solvers.