<Back to Index>

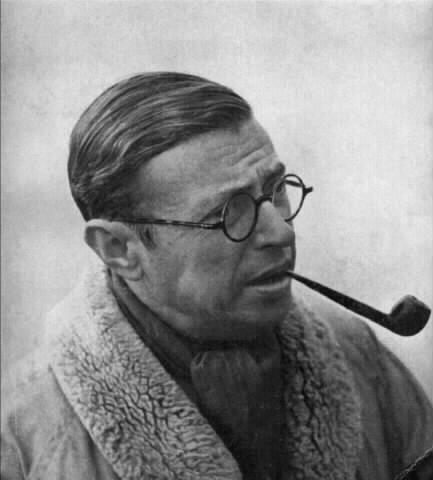

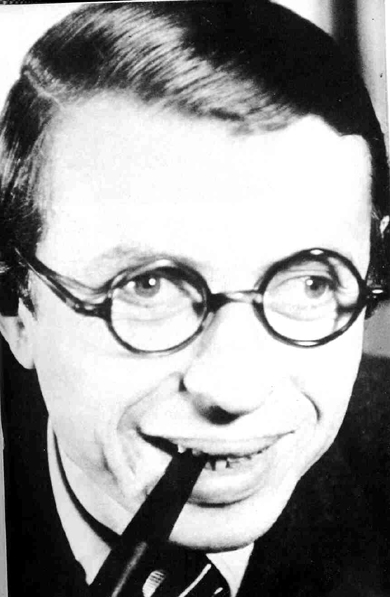

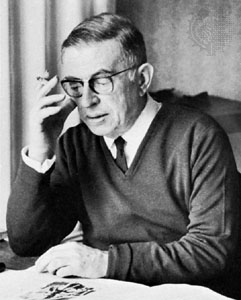

- Philosopher Jean Paul Charles Aymard Sartre, 1905

- Painter Abraham Mignon, 1640

- Prime Minister of Italy Giovanni Spadolini, 1925

PAGE SPONSOR

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French existentialist philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary critic. He was one of the leading figures in 20th century French philosophy, existentialism, and Marxism, and his work continues to influence fields such as Marxist philosophy, sociology, critical theory and literary studies. Sartre was also noted for his long polyamorous relationship with the feminist author and social theorist, Simone de Beauvoir. He was awarded the 1964 Nobel Prize in Literature but refused the honour.

Jean-Paul Sartre was born in Paris as the only child of Jean-Baptiste Sartre, an officer of the French Navy, and Anne-Marie Schweitzer. His mother was of Alsatian origin and the first cousin of Nobel Prize laureate Albert Schweitzer. (Her father, Charles Schweitzer, was the older brother of Albert Schweitzer's father, Louis Théophile.) When Sartre was 15 months old, his father died of a fever. Anne-Marie moved back to her parents' house in Meudon, where Sartre was raised with help from her father, a professor of German, who taught Sartre mathematics and introduced him to classical literature at a very early age. At twelve his mother remarried and the family moved to La Rochelle, where he was frequently bullied.

As a teenager in the 1920s, Sartre became attracted to philosophy upon reading Henri Bergson's Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. He studied and earned a doctorate in philosophy in Paris at the École Normale Supérieure, an institution of higher education that was the alma mater for several prominent French thinkers and intellectuals. It was at ENS that Sartre began his life long, sometimes fractious, friendship with Raymond Aron. Sartre was influenced by many aspects of Western philosophy, absorbing ideas from Kant, Hegel, Kierkegaard, Husserl and Heidegger, among others. In 1929 at the École Normale, he met Simone de Beauvoir, who studied at the Sorbonne and later went on to become a noted philosopher, writer, and feminist. The two became inseparable and lifelong companions, initiating a romantic relationship, though they were not monogamous. Sartre served as a conscript in the French Army from 1929 to 1931 and he later argued in 1959 that each French person was responsible for the collective crimes during the Algerian War of Independence.

Together, Sartre and de Beauvoir challenged the cultural and social assumptions and expectations of their upbringings, which they considered bourgeois, in both lifestyle and thought. The conflict between oppressive, spiritually destructive conformity (mauvaise foi, literally, "bad faith") and an "authentic" way of "being" became the dominant theme of Sartre's early work, a theme embodied in his principal philosophical work L'Être et le Néant (Being and Nothingness) (1943). Sartre's introduction to his philosophy is his work Existentialism is a Humanism (1946), originally presented as a lecture.

In 1939 Sartre was drafted into the French army, where he served as a meteorologist. He was captured by German troops in 1940 in Padoux, and he spent nine months as a prisoner of war — in Nancy and finally in Stalag 12D, Trier, where he wrote his first theatrical piece, Barionà, fils du tonnerre, a drama concerning Christmas. It was during this period of confinement that Sartre read Heidegger's Sein und Zeit (Being and Time), later to become a major influence on his own essay on phenomenological ontology. Because of poor health (he claimed that his poor eyesight and exotropia affected his balance) Sartre was released in April 1941. Given civilian status, he recovered his position as a teacher at Lycée Pasteur near Paris, settled at the Hotel Mistral near Montparnasse in Paris, and was given a new position at Lycée Condorcet, replacing a Jewish teacher who had been forbidden to teach by Vichy law. After coming back to Paris in May 1941, he participated in the founding of the underground group Socialisme et Liberté with other writers Simone de Beauvoir, Merleau - Ponty, Jean-Toussaint Desanti and his wife Dominique Desanti, Jean Kanapa, and École Normale students. In August, Sartre and Beauvoir went to the French Riviera seeking the support of André Gide and André Malraux. However, both Gide and Malraux were undecided, and this may have been the cause of Sartre's disappointment and discouragement. Socialisme et liberté soon dissolved and Sartre decided to write, instead of being involved in active resistance. He then wrote Being and Nothingness, The Flies, and No Exit, none of which was censored by the Germans, and also contributed to both legal and illegal literary magazines. After August 1944 and the Liberation of Paris, he wrote Anti-Semite and Jew. In the book he tries to explain the etiology of "hate" by analyzing so-called antisemitic hate. Sartre was a very active contributor to Combat, a newspaper created during the clandestine period by Albert Camus,

a philosopher and author who held similar beliefs. Sartre and Beauvoir

remained friends with Camus until 1951, after the publication of Camus' The Rebel. Later, while Sartre was labeled by some authors as a resistant, the French philosopher and resistant Vladimir Jankelevitch criticized

Sartre's lack of political commitment during the German occupation, and

interpreted his further struggles for liberty as an attempt to redeem

himself. According to Camus, Sartre was a writer who resisted, not a resistor who wrote. After the war ended Sartre established Les Temps Modernes (Modern Times), a quarterly literary and political review,

and started writing full time as well as continuing his political

activism. He would draw on his war experiences for his great trilogy of

novels, Les Chemins de la Liberté (The Roads to Freedom) (1945 – 1949). The first period of Sartre's career, defined in large part by Being and Nothingness (1943), gave way to a second period as a politically engaged activist and intellectual. His 1948 work Les Mains Sales (Dirty Hands)

in particular explored the problem of being both an intellectual at the

same time as becoming "engaged" politically. He embraced Marxism (but didn't join the Communist Party) and took a prominent role in the struggle against French rule in Algeria. He became perhaps the most eminent supporter of the FLN in the Algerian War and was one of the signatories of the Manifeste des 121. Furthermore, he had an Algerian mistress, Arlette Elkaïm, who became his adopted daughter in 1965. He opposed the Vietnam War and, along with Bertrand Russell and others, organized a tribunal intended to expose U.S. war crimes, which became known as the Russell Tribunal in 1967. His major defining work after 1955, the Critique de la raison dialectique (Critique of Dialectical Reason) appeared in 1960 (a second volume appeared posthumously). In Critique,

Sartre set out to give Marxism a more vigorous intellectual defense

than it had received up until then; he ended by concluding that Marx's

notion of "class"

as an objective entity was fallacious. Sartre's emphasis on the

humanist values in the early works of Marx led to a dispute with a

leading leftist intellectual in France in the 1960s, Louis Althusser, who claimed that the ideas of the young Marx were decisively superseded by the "scientific" system of the later Marx. Sartre went to Cuba in the '60s to meet Fidel Castro and spoke with Ernesto "Che" Guevara.

After Guevara's death, Sartre would declare him to be "not only an

intellectual but also the most complete human being of our age" and the "era's most perfect man." Sartre would also compliment Che Guevara by professing that "he lived his

words, spoke his own actions and his story and the story of the world

ran parallel." During a collective hunger strike in 1974, Sartre visited Red Army Faction leader Andreas Baader in Stammheim Prison and criticized the harsh conditions of imprisonment. In 1964, Sartre renounced literature in a witty and sardonic account of the first ten years of his life, Les mots (Words). The book is an ironic counterballast to Marcel Proust, whose reputation had unexpectedly eclipsed that of André Gide (who had provided the model of littérature engagée for

Sartre's generation). Literature, Sartre concluded, functioned

ultimately as a bourgeois substitute for real commitment in the world.

In October 1964, Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature but he declined it. He was the first Nobel Laureate to voluntarily decline the prize, and he had previously refused the Légion d'honneur,

in 1945. The prize was announced on 22 October 1964; on 14 October,

Sartre had written a letter to the Nobel Institute, asking to be

removed from the list of nominees, and that he would not accept the

prize if awarded, but the letter went unread; on 23 October, Le Figaro published

a statement by Sartre explaining his refusal. He said he did not wish

to be "transformed" by such an award, and did not want to take sides in

an East vs. West cultural struggle by accepting an award from a

prominent Western cultural institution. After the prize award he tried to escape the media by hiding in the house of Simone's sister Hélène de Beauvoir in Goxwiller in Alsace. Though

his name was then a household word (as was "existentialism" during the

tumultuous 1960s), Sartre remained a simple man with few possessions,

actively committed to causes until the end of his life, such as the student revolution strikes in Paris during the summer of 1968 during which he was arrested for civil disobedience. President Charles de Gaulle intervened and pardoned him, commenting that "you don't arrest Voltaire." In 1975, when asked how he would like to be remembered, Sartre replied: I would like [people] to remember Nausea, [my plays] No Exit and The Devil and the Good Lord, and then my two philosophical works, more particularly the second one, Critique of Dialectical Reason. Then my essay on Genet, Saint Genet... If

these are remembered, that would be quite an achievement, and I don't

ask for more. As a man, if a certain Jean-Paul Sartre is remembered, I

would like people to remember the milieu or historical situation in

which I lived,... how I lived in it, in terms of all the aspirations

which I tried to gather up within myself. Sartre's

physical condition deteriorated, partially because of the merciless

pace of work (and using drugs for this reason, e.g., amphetamine) he put himself through during the writing of the Critique and a massive analytical biography of Gustave Flaubert (The Family Idiot), both of which remained unfinished. Sartre became almost completely blind in 1973. He died 15 April 1980 in Paris from edema of the lung. Sartre lies buried in Cimetière de Montparnasse in

Paris. His funeral was well attended, with estimates of the number of

mourners along the two hour march ranging from 15,000 to over 50,000.