<Back to Index>

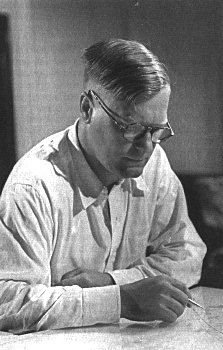

- Physicist William George Penney, 1909

- Poet Samuel Ampzing, 1590

- Social Democratic Leader Victor Adler, 1852

PAGE SPONSOR

William George Penney, Baron Penney OM, KBE (24 June 1909 – 3 March 1991) was a British physicist who was responsible for the development of British nuclear technology following World War II. A mathematician by training, he became an expert on wave dynamics. He was one of the world's leading authorities on the effects of nuclear weapons; and he was tasked with the development of the British atomic bomb.

The son of a sergeant major in the Royal Army Ordnance Corps, Bill Penney was born in Gibraltar on 24 June 1909, and grew up in Sheerness, Kent, and attended the Colchester Royal Grammar School. From 1924 to 1926, he was educated at Sheerness Technical High School for Boys where he displayed a marked talent for mathematics.

In 1927, while working as a laboratory assistant, his mathematical ability gained him a scholarship to the Imperial College of Science, Technology and Medicine. He was awarded the Governor's Prize for Mathematics and graduated with a B.Sc. with First Class Honours in 1929 at age 20. Continuing his studies at the University of London, he obtained his Ph.D. in 1931 at age 22. He spent two years in the United States at the University of Wisconsin – Madison as a Commonwealth Fund Fellow. He returned to England and with the award of the 1851 Exhibition Scholarship he attended Trinity College, Cambridge, where he carried out theoretical investigations on the structure of metals and the magnetic properties of crystals. He obtained a doctorate from the University of Cambridge in 1935 on the application of quantum mechanics to the physics of crystals. In 1936, he was elected to the Stokes studentship at Pembroke College, Cambridge, but in the same year he returned to London and was appointed Reader in Mathematics at Imperial College London, a post he held from 1936 to 1945. His real love was mathematics and pure research in physics. As a recognised prodigy at Imperial College he was set for a distinguished academic career until World War II intervened.

Penney's area of scientific specialty was the physics of hydrodynamic waves, both shock waves and gravity waves. During the early years of World War II, he was loaned out to the Home Office and the Admiralty where

he investigated problems connected with the properties of under water

blast waves from high explosives, a subject of great importance in

designing ships and torpedoes. Penney designed and supervised

development of the Mulberry harbours that would be placed off the Normandy beaches during the D-Day invasion. These mobile breakwaters would protect the landing craft and troops

from the Atlantic rollers. In 1943, he was released from his duties at

Imperial College to work on the Tube Alloys project, and shortly before D-Day in 1944 he returned to America to work at Los Alamos as part of the British delegation to the Manhattan Project. On

the Manhattan Project, Penney worked on the use of the atomic bomb, its

effects and in particular the height at which it should be detonated.

He quickly gained recognition for his varied talents, his technical and

policy skills, his leadership qualities, and for his ability to work in

harmony with others. Within a few weeks of his arrival he was added to

the core group of scientists who made all key decisions in the

direction of the program. Other members of that team included J. Robert Oppenheimer, Captain William Parsons (USN), John von Neumann and Norman F. Ramsey. One

of Penney's assignments at Los Alamos was to predict the damage effects

from the blast wave of an atomic bomb. On 16 July 1945, Penney was an

observer at the Trinity test detonation.

He was there to observe the effect of radiant heating in igniting

structural materials, and had also designed apparatus to monitor the

blast effect of the explosions. The Americans considered him to be

among the five most distinguished British contributors to the work.

General Leslie Groves, overall director of the Manhattan Project, later wrote: vital

decisions were reached only after the most careful consideration and

discussion with the men I thought were able to offer the soundest

advice. Generally, for this operation, they were Oppenheimer, Von

Neumann, Penney, Parsons and Ramsey. Penney

went to Washington for a top secret meeting for a committee target

selection. He recommended Hiroshima and Nagasaki because of the hills

surrounding the environs which he said would create maximum

devastation. He gave valuable advice to the height of the bomb

detonation so that the fireball would not touch the earth and also for

no permanent radiation contamination on the ground. The U.S. nuclear team repeatedly attempted to recruit Penney as a permanent member, without success. Along with RAF Group Captain Leonard Cheshire, he accompanied the American Team to Tinian Island from which the Hiroshima and Nagasaki missions

were flown. On 9 August 1945 he witnessed the bombing of Nagasaki. The

US authorities had controversially stopped them seeing the Hiroshima

detonation, but at the last minute Penney and Cheshire were granted

permission to fly in the B-29 Big Stink, one of the observation planes that accompanied the Nagasaki mission bomber Bockscar. Due to the belated permissions, Big Stink missed

its rendezvous with the bomber at Nagasaki. They did see the Nagasaki

detonation from the air at a distance, making him one of the few people

in the world to witness first-hand either of the Japanese detonations

from the air. As the leading expert on the effects of nuclear weapons,

Penney was a member of the team of scientists and military analysts who

entered Hiroshima and Nagasaki following the Japanese surrender 15

August 1945 to assess the effects of the nuclear weapons. At the end of the war the British government, now under Labour Prime Minister Clement Attlee, believed that America would share the technology that British leaders saw as a joint discovery under the terms of the 1943 Quebec Agreement.

In December 1945 PM Attlee ordered the construction of an atomic pile

to produce plutonium and requested a report to detail requirements for

Britain's atomic bombs. Penney returned to England and intended to

resume his academic career, but was approached by C.P. Snow and asked to take up post as Chief Superintendent Armament Research (CSAR, called "Caesar") at Fort Halstead in

Kent, as he suspected Britain was going to have to build an atomic bomb

of its own and the government wanted Penney in this job. As CSAR he was responsible for all types of armaments research. In 1946, at the request of General Leslie Groves and the US Navy, Penney returned to the United States where he was put in charge of the blast effects studies for Operation Crossroads. In July, he was present at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands and

wrote the after action reports on the effects of the two A-Bomb

detonations. His reputation was further enhanced when, after the

sophisticated test gauges failed, he was able to determine the blast power

using observations from simpler devices. However the passing of the McMahon Act (Atomic

Energy Act) by the Truman administration in August 1946 made it clear

that Britain would no longer be allowed access to US atomic

research. So Penney left the United States and returned to England

where he initiated his plans for an Atomics Weapons Section, submitting

them to the Lord Portal (Marshal

of the Royal Air Force) in November 1946. During the winter of

1946 - 1947, Penney returned once again to the United States, where he

served as a scientific adviser to the British representative at the

American Atomic Energy Commission.

With almost all other aspects of atomic co-operation between the

countries at an end, Penney's personal role was seen as keeping the

contact alive between the parties. Attlee's

government decided that Britain required the atomic bomb to maintain

its position in world politics. In the words of Foreign Secretary Ernest Bevin - "We've got to have it and it's got to have a bloody Union Jack on it." Officially,

the decision to proceed with the British atomic bomb project was made

in January 1947 - however arrangements were already under way. The

necessary plutonium was on order from Harwell and in the Armaments Research Department of the Ministry of Supply, an Atomic Weapons Section was being organised. The project was based at the Royal Arsenal, Woolwich, and was code-named High Explosive Research (or HER). In

May 1947, Penney was officially named to head the HER project. The

following month Penney began assembling teams of scientists and

engineers to work on the new technologies that had to be developed. In

June 1947, Penney gathered his fledgling team in the library at the

Royal Arsenal and gave a two-hour talk on the principles of the atomic

bomb. Centered at Fort Halstead, the work proceeded on schedule and, in

1950, it was realised that arrangements had to be made to test the

first bomb, since it would be ready within two years. Due

to the work being spread across a number of test facilities in the UK,

that were linked to the project with confusing lines of authority and

responsibility, it was realized that a single site was required. The

bomb design was also complex and innovative - although it started off

based on the design established with the Nagasaki bomb, it used

completely new methods of arming and of electrical detonation. In April

1950 an abandoned WWII airfield, RAF Aldermaston in

Berkshire was selected as the permanent home for Britain's nuclear

weapons programme. Construction began and in 1951 the first scientific

staff arrived at Aldermaston - soon after this, the HER project vacated

the Royal Arsenal. On 3 October 1952, under the code-name "Operation Hurricane", the first British nuclear device was successfully detonated off the west coast of Australia in the Monte Bello Islands.

This was a remarkable achievement and confirmed the qualities of

scientific ability and leadership skills of Penney. On his return to

England, Penney received a knighthood from Queen Elizabeth II. He

was also aware of the public relations issues associated with the

tests, and made clear speaking presentations to the Australian press. Before one series of tests the Australian High Commissioner described

his press presence: "Sir William Penney has established in Australia a

reputation which is quite unique: his appearance, his obvious sincerity

and honesty, and the general impression he gives that he would rather

be digging his garden – and would be, but for the essential nature of

his work – have made him a public figure of some magnitude in

Australian eyes". In 1953, he was offered a Chair at the University of Oxford but

declined in order to continue work on nuclear technology as director of

the Aldermaston site which was now officially named the Atomic Weapons Research Establishment (AWRE).

In 1954, nuclear development was transferred from the Ministry of Supply (MoS) to the newly formed United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (UKAEA).

From 1954 to 1967, Sir William served on the UKAEA Board, becoming

Chairman in 1962. Under his leadership the first British hydrogen bomb

was developed and tested in May 1957.

The Rt Hon Lord Penney, OM, KBE, MA, PhD, DSc, HonFCGI, FIC, FRS, was Rector of Imperial College London from 1967 - 1973. The college built and named the William Penney Laboratory after him. Additionally, he has a Hall of Residence named after him at Imperial College's campus in Silwood Park, near Ascot. In later years he admitted to qualms about his work but felt it was necessary. When aggressively questioned by the McClelland Royal Commission investigating

the test programmes at Monte Bello and Maralinga in 1985, he

acknowledged that at least one of the 12 tests probably had unsafe

levels of fallout. However he maintained that due care was taken and

that the tests conformed to the internationally accepted safety

standards of the time, a position which was confirmed from official

records by Lorna Arnold. McClelland broadly accepted Penney's view but anecdotal evidence to the contrary

received wide coverage in the press. By promoting a more Australian

nationalist view, then current in the government of Bob Hawke, McClelland had also identified "villains" in the previous Australian and British administrations. As

a senior witness Penney bore the brunt of the allegations, and his

health was badly affected by the experience. He died a few years later

at his home in the village of East Hendred, at the age 81. In his obituary in the New York Times he was credited as the father of the British atomic bomb. The Guardian described him as its "guiding light", and

his scientific and administrative leadership was said to be crucial in

its successful and timely creation. His leadership of the team that

exploded the first British hydrogen bomb at Christmas Island was

instrumental in restoring the exchange of nuclear technology between

Britain and the USA in 1958, and he was credited as playing a leading

part in the negotiations which led to the treaty forbidding atmospheric nuclear tests in 1963. During his lifetime William Penney was made a Commonwealth Fund Fellow at University of Wisconsin – Madison (1932); Fellow of the Royal Society (1946); Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh (1970). Among the honours he received was the Rumford Medal by the Royal Society (1966). For services to the United States, he was one of the first recipients of the United States Medal of Freedom (with Silver Palm), awarded by President Harry S. Truman. For his services to Britain he was awarded O.B.E. (1946); appointed to the Order of the British Empire as Knight Commander (1952); was awarded a life peerage taking the title Baron Penney, of East Hendred in the Royal County of Berkshire (1967); awarded the Order of Merit (1969). He served on the board of the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority (from 1954 – 1967) and became its Chairman (1962 – 1967).