<Back to Index>

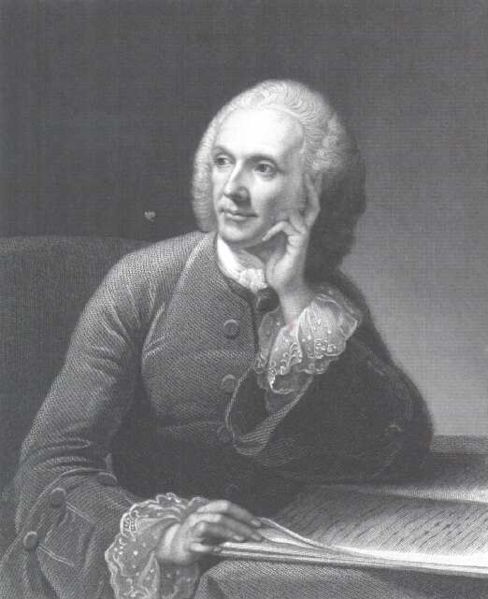

- Anatomist William Hunter, 1718

- Engraver Claude Mellan, 1598

- Emperor of the Song Dynasty Qinzong, 1100

PAGE SPONSOR

William Hunter FRS (23 May 1718 – 30 March 1783) was a Scottish anatomist and physician. He was a leading teacher of anatomy, and the outstanding obstetrician of his day. His guidance and training of his ultimately more famous brother, John Hunter, was also of great importance.

He was born at Long Calderwood - now a part of East Kilbride, South Lanarkshire - the elder brother of John Hunter. After studying divinity at the University of Glasgow, he went into medicine in 1737, studying under William Cullen.

Arriving in London, Hunter became resident pupil to William Smellie (1741 – 44) and he was trained in anatomy at St George's Hospital, London, specialising in obstetrics. He followed the example of Smellie in giving a private course on dissecting, operative procedures and bandaging, from 1746. His courtly manners and sensible judgement helped him to advance until he became the leading obstetric consultant of London. Unlike Smellie, he did not favour the use of forceps in delivery. Stephen Paget said of him:

- "He never married; he had no country house; he looks, in his portraits, a fastidious, fine gentleman; but he worked till he dropped and he lectured when he was dying."

To orthopaedic surgeons he is famous for his studies on bone and cartilage. In 1743 he published the paper On the structure and diseases of articulating cartilages -

which is often cited - especially the following sentence: “If we

consult the standard Chirurgical Writers from Hippocrates down to the

present Age, we shall find, that an ulcerated Cartilage is universally

allowed to be a very troublesome Disease; that it admits of a Cure with

more Difficulty than carious Bone; and that, when destroyed, it is not

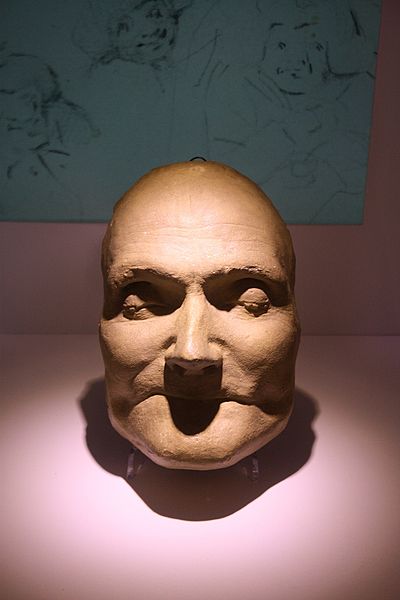

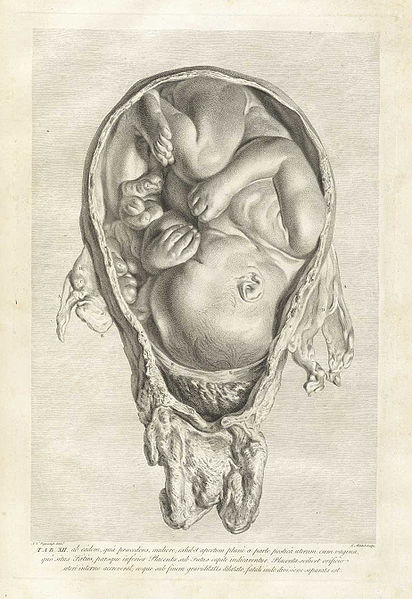

recovered”. In 1764, he became physician to Queen Charlotte. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in 1767 and Professor of Anatomy to the Royal Academy in 1768. In 1768 he built the famous anatomy theatre and museum in Great Windmill Street, Soho, where the best British anatomists and surgeons of the period, including his brother John, were trained. His greatest work was Anatomia uteri umani gravidi [The anatomy of the human gravid uterus exhibited in figures] (1774), with plates engraved by Rymsdyk (1730 – 90), and published by the Baskerville Press. He chose as a model for clear, precise but schematic illustration of anatomic dissections the drawings by Leonardo da Vinci conserved in the Royal Collection at Windsor: Kenneth Clark considered him responsible for the Eighteenth century rediscovery of Leonardo's drawings in England. To aid his teaching of dissection, in 1775 Hunter commissioned sculptor Agostino Carlini to make a cast of the flayed but muscular corpse of a recently executed criminal, a smuggler. He was professor of anatomy at the Royal Academy of Arts in London from 1769 until 1772. He was interested in arts, and had strong connections to the artistic world. In 1770 he built himself a house in Glasgow fully equipped for the practice of his science, and this formed the nucleus of the University of Glasgow's Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery. It

has been alleged that Hunter (and his brother John) were involved with

either commissioning the murder or showing a callous disregard for

where his corpses came from (and his former tutor William Smellie). The supporting evidence for this theory includes the large number of pregnant corpses Hunter was able to obtain. William

Hunter was an avid antique coin collector and the Hunter Coin cabinet

in the Hunterian Museum is one of the world's great collections. According to the Preface of Catalogue of Greek Coins in the Hunterian Collection (Macdonald 1899), Hunter purchased many important collections, including those of Horace Walpole and the bibliophile Thomas Crofts. King George III even donated an Athenian gold piece. When the famous book collection of Anthony Askew, the Bibliotheca Askeviana,

was auctioned off upon Askew's death in 1774, Hunter purchased many

significant volumes in the face of stiff competition from the British Museum. He died in 1783, aged 64, and was buried in London at St James's, Piccadilly.