<Back to Index>

- Historian Carl Jacob Christoph Burckhardt, 1818

- Composer Gilardo Gilardi, 1889

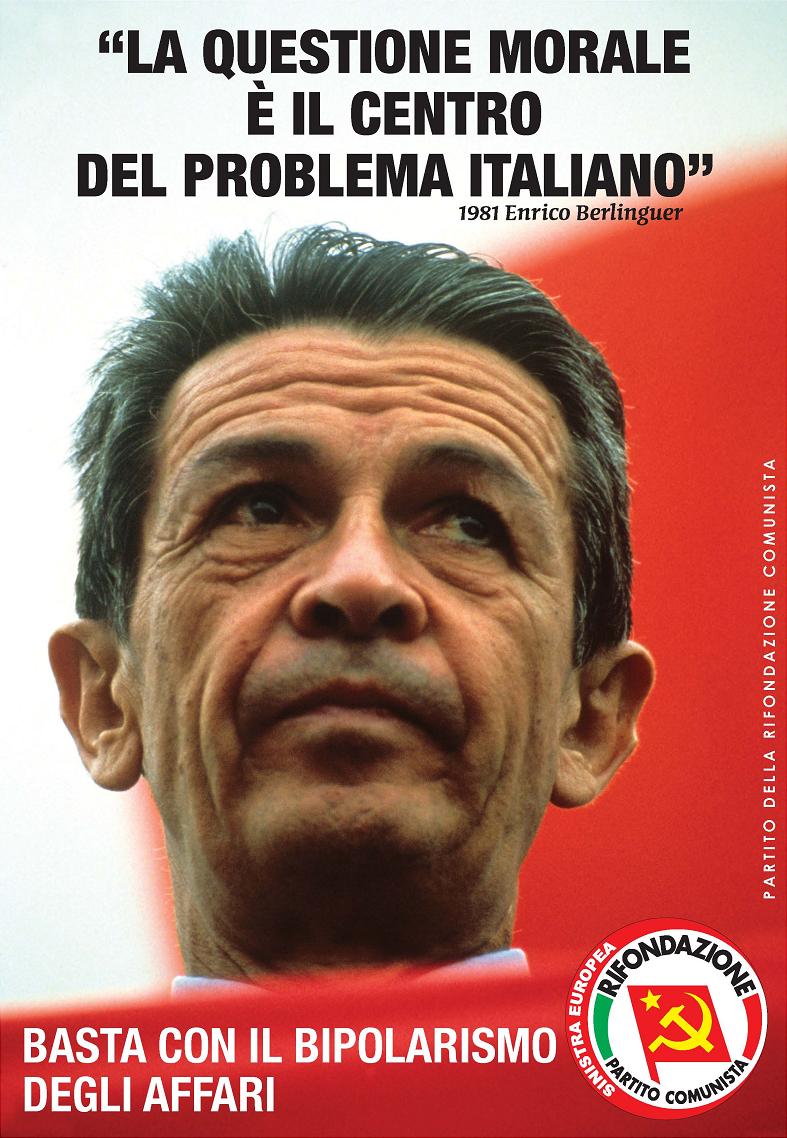

- General Secretary of the Partito Comunista Italiano Enrico Berlinguer, 1922

PAGE SPONSOR

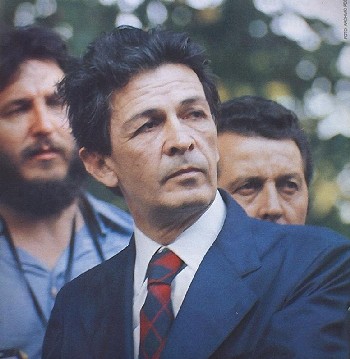

Enrico Berlinguer (25 May 1922 – 11 June 1984) was an Italian politician; he was national secretary of the Italian Communist Party (Partito Comunista Italiano or PCI) from 1972 until his death.

The son of Mario Berlinguer and Maria Loriga, Enrico Berlinguer was born in Sassari, Italy, to a noble and important Sardinian family, in a notable cultural context, with family ties and political contacts that would heavily influence his life and career. His surname 'Berlinguer' is of Catalan origin, a reminder of the period when Sardinia was part of the dominions of the Crown of Aragon. He was a cousin of Francesco Cossiga (who was a leader of the Italian Christian Democrats and later became a President of the Italian Republic), and both were relatives of Antonio Segni, another Christian Democrat leader and President of the Republic. Enrico's grandfather, Enrico Berlinguer Sr., was the founder of La Nuova Sardegna, an important Sardinian newspaper, and a personal friend of Giuseppe Garibaldi and Giuseppe Mazzini, whom he had helped in his attempts through his parliamentary work to improve the sad conditions on the island.

In 1937 Berlinguer had his first contacts with Sardinian anti-Fascists, and in 1943 formally entered the Italian Communist Party, soon becoming the secretary of the Sassari section. The following year a riot exploded in the town; he was involved in the disorders and was arrested, but was discharged after 3 months of prison.

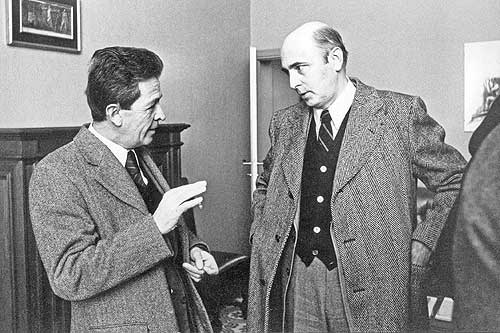

Immediately after his detention ended, his father brought him to Salerno, the town in which the Royal family and the government had taken refuge after the armistice between Italy and the Allies. In Salerno his father introduced him to Palmiro Togliatti, the most important leader of the Communist Party.

Togliatti sent Berlinguer back to Sardinia to prepare for his political career. At the end of 1944, Togliatti appointed him to the national secretariat of the Communist Organisation for Youth (FGCI); he was soon sent to Milan, and in 1945 he was appointed to the Central Committee as a member.

In 1946 Togliatti became the national secretary (the highest political role) of the Party, and called Berlinguer to Rome,

where his talents let him enter the national leadership only two years

after (at the age of 26, one of the youngest members ever admitted); in

1949 he was named national secretary of the FGCI, a post he held until

1956. The year after he was named president of the World Federation of Democratic Youth,

an international Communist front organisation. In 1957 Berlinguer, as a

member of the central school of the PCI, abolished the obligatory visit

to the Soviet Union, which included political training, that was until then necessary for admission to the highest positions in the PCI. Berlinguer's

career was obviously carrying him towards the highest positions in the

party. After having held many responsible posts, in 1968 he was elected

a deputy for the first time for the electoral district of Rome. The following year he was elected deputy national secretary of the party (the secretary being Luigi Longo). In this role he took part in the 1969 international conference of the Communist parties in Moscow, where his delegation disagreed with the "official" political line, and refused to support the final report. Berlinguer's

unexpected stance made waves: he gave the strongest speech by a major

Communist leader ever heard in Moscow. He refused to "excommunicate"

the Chinese communists, and directly told Leonid Breznev that the invasion of Czechoslovakia by the Warsaw Pact countries (which he termed the "tragedy in Prague") had made clear the considerable differences within the Communist movement on fundamental questions such as national sovereignty, socialist democracy, and the freedom of culture. Already

a prominent leader in the party, Berlinguer was elected to the position

of national secretary in 1972 when Luigi Longo resigned on grounds of

ill health. In 1973, having been hospitalized after a car accident during a visit to Bulgaria (now widely considered an attempt on his life on orders from Moscow), Berlinguer wrote three famous articles ("Reflections on Italy", "After the facts of Chile" and "After the Coup [in Chile]") for the intellectual weekly magazine of the party, Rinascita.

In these he presented the strategy of the so-called Historic

Compromise, a proposed coalition between the Italian Communist Party

and the Christian Democrats to grant Italy a period of political

stability, at a time of severe economic crisis and in a context in

which some forces were allegedly manoeuvering for a coup d'état

in Italy. The following year in Belgrade Berlinguer met with Yugoslav president Josip Broz Tito, towards the ends of further developing his relationships with the major Communist parties of Europe, Asia and Africa. In

1976, in Moscow again, Berlinguer confirmed the autonomous position of

the PCI vis-à-vis the Soviet Communist Party. Before 5,000

Communist delegates he spoke of a "pluralistic system" (translated by

the interpreter as "multiform"), referring to the PCI's intentions to

build "a socialism that we believe necessary and possible only in

Italy." When

Berlinguer finally got to the PCI's condemnation of any kind of

"interference", the rupture with the Soviets was complete (nonetheless,

the party still for some years received money from Moscow). Since Italy

was suffering the "interference" of NATO,

the Soviets said, it seemed that the only interference that the Italian

Communists could not suffer was the Soviet one. In an interview with Corriere della Sera Berlinguer declared that he felt "safer under NATO's umbrella." In 1977, at a meeting in Madrid between Berlinguer, Santiago Carrillo of the Spanish Communist Party and Georges Marchais of the French Communist Party, the fundamental lines of Eurocommunism were

laid out. A few months later Berlinguer was again in Moscow, where he

gave another speech which was poorly received by his hosts, and

published by Pravda only in a censored version. Berlinguer,

moving step by step, was building a consensus in the PCI towards a

rapprochement with other components of society. After the surprising

opening of 1970 toward conservatives, and the still discussed proposal

of the Historic Compromise, he published a correspondence with Monsignor Luigi Bettazzi, the Bishop of Ivrea; it was an astonishing event, since Pope Pius XII had excommunicated the Communists soon after World War II,

and the possibility of any relationship between communists and

Catholics seemed very unlikely. This act also served to counteract the

allegation, commonly and popularly expressed, that the PCI was

protecting leftist terrorists,

in the harshest years of terrorism in Italy. In this context the PCI

opened its doors to many Catholics, and a debate started about the

possibility of contact. Notably, Berlinguer's strictly Catholic family

was not brought out of its strictly respected privacy. In the general

election of June 1976, the PCI gained 34.4% of the vote. In

Italy a so-called "government of national solidarity" was ruling, but

Berlinguer claimed that in an emergency government, a strong and

powerful cabinet to solve a crisis of exceptional gravity was needed.

On 16 March 1978, Aldo Moro, President of the Christian Democratic Party, was kidnapped by the Red Brigades, an ultra-left terrorist group, on the day that the new government was going to be sworn in before parliament. During

this crisis, Berlinguer adhered to the so-called "Front of Firmness,"

refusing to negotiate with terrorists. (The Red Brigades had proposed

to liberate Moro in exchange for the release of some imprisoned

terrorists.) Despite the PCI's firm stand against terrorism, the Moro

incident left the party more isolated. In June the PCI gave its approval, and ultimately active support, to a campaign against President Giovanni Leone, accused of being involved in the Lockheed bribery scandal. This resulted in the President's resignation. Berlinguer also supported the election of the veteran Socialist Sandro Pertini as President of Italy, but his presidency did not produce the effects that the PCI had hoped for. In

Italy, after a new president is elected, the government resigns. The

PCI expected Pertini to use his influence in their favour. But the President was influenced by other political leaders like Giovanni Spadolini of the Italian Republican Party and Bettino Craxi of the Italian Socialist Party, and the PCI remained out of the government. During these years the PCI governed many Italian regions, sometimes more than half of them. Notably, the regional government of Emilia - Romagna and Tuscany was

concrete proof of PCI's governmental capabilities. In this period,

Berlinguer turned his attention to the exercise of local power, to show

that "the trains could run on time" under the PCI. He personally took

part in electoral campaigns in the provinces and local councils. While

other parties sent only local leaders, this helped the party to win

many elections at these levels. In 1980 the PCI publicly condemned the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan;

Moscow then immediately sent Marchais to Rome, to try to bring

Berlinguer into line, but Marchais was received with a notable

coldness. The break with the Soviets and other Communist parties became

clear when the PCI did not participate in the 1980 international

conference of Communist parties held in Paris. Instead Berlinguer made an official visit to China. In November in Salerno,

Berlinguer declared that the idea of a possible Historic Compromise had

been put aside; it would be replaced with the idea of the "democratic

alternative." In

1981 Berlinguer said that, in his personal opinion, "the progressive

force of the October Revolution had been exhausted." The PCI criticised

the "normalisation" of Poland and very soon the PCI's split with the Soviet Communist Party became definitive and official, followed by a long polemic between Pravda and L'Unità (the official newspaper of PCI), not made any milder after the meeting with Fidel Castro in Havana. On

an internal side, Berlinguer's last major statement was a call for the

solidarity among the leftist parties. In June 1984 Berlinguer suddenly left the stage during a speech at public meeting in Padua:

he had suffered a brain haemorrhage, and died three days later. More

than a million citizens attended his funeral, one of the biggest in

Italy's history.

Enrico

Berlinguer has been defined in many ways, but he was generally

recognised for political coherence and a certain courage, together with

a rare personal and political intelligence. A serious man, he was

sincerely respected even by his opponents, and his three days' agony

was followed with great attention by the general population. His

funeral was followed by a large number of people, perhaps among the

highest ever seen in Rome. The

most important political act of his career in the PCI was undoubtedly

the dramatic break with Soviet Communism, the so-called strappo, together with the creation of Eurocommunism, and his substantial work towards contact with the moderate (and particularly the catholic) half of the country. Berlinguer

nevertheless had many enemies. An internal opposition in the PCI

claimed that he had turned a workers' party into a sort of bourgeois

revisionist club. External opposition figures noted that strappo took

several years to be completed; this was seen as evidence that there had

been no definitive decision on the point. The acceptance of NATO is

however generally seen as evidence of the genuine autonomy of the PCI's

position. All

the work of Berlinguer, however, even if supported by a notably

successful Communist local governments, was unable to bring the PCI

into the government. Berlinguer's final platform, the "democratic

alternative," was never translated into reality. Within a decade of his

death the Soviet Union, the Christian Democrats and the PCI all

disappeared, transforming Italian politics beyond recognition.