<Back to Index>

- Jurist Carlos Saavedra Lamas, 1878

- Writer Johan Nordahl Brun Grieg, 1902

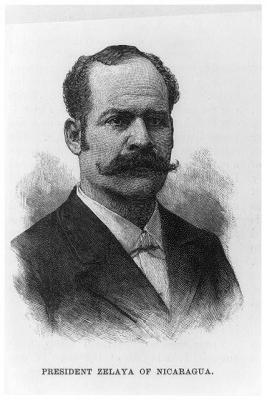

- President of Nicaragua José Santos Zelaya López, 1853

PAGE SPONSOR

José Santos Zelaya López (1 November 1853 Managua - 17 May 1919 New York City) was the President of Nicaragua from 25 July 1893 to 21 December 1909.

He was a son of José María Zelaya Fernández, born in Olancho Department, Honduras, and wife Juana López.

Zelaya was of Nicaragua's liberal party and enacted a number of progressive programs, including improving public education, building railroads, and establishing steam ship lines and enacting constitutional rights that provided for equal rights, property guarantees, habeas corpus, compulsory vote, compulsory education, the protection of arts and industry, minority representation, and the separation of state powers. However, his wish for national sovereignty often led him to policies contrary to colonialist interests.

In 1894, he took control of the Mosquito Coast by military force; it had long been the subject of dispute, home to a native kingdom claimed as a protectorate by the British Empire.

Zelaya's fortitude paid off, and the United Kingdom, not wishing to go

to war for this distant land of little value to the Empire, recognized

Nicaraguan sovereignty over the area.

José Santos Zelaya was reelected president in 1902 and again in 1906. Both under questionable circumstances for his original rise to the presidency was by a military coup.

The possibility of building a canal across the isthmus of Central America had been the topic of serious discussion since the 1820s, and Nicaragua was long a favored location. When the United States shifted its interests to Panama, Zelaya negotiated with Germany (who happened to be in the middle of a cold war with the U.S over Caribbean ports) and Japan in an unsuccessful effort to have a canal constructed in his state. Fearful that president Zelaya might generate an alternative foreign alignment in the region, the U.S. labeled him a tyrant in opposition to U.S. planned hegemony.

José Zelaya had ambitions of reuniting the United States of Central America, with, he hoped, himself as national president. With this aim in mind, he gave aid to liberal federalist factions in other Central American nations. This threatened to create a full scale Central American war which would endanger the United States Panamanian canal and give European nations, such as Germany, an excuse to intervene to protect the collection of their bank's payments in the region or if failing that then demand a land concession.

The Zelaya administration had growing friction with the United States government, for example while the French government had inquired to the U.S. whether a loan to Nicaragua would be deemed unfriendly, the U.S. secretary of state required the loan to be conditional on U.S. relations. After the loan was pending on the Paris stock exchange, the U.S. further isolated Nicaragua by claiming any money Zelaya would receive "would be without doubt spent to purchase munitions to oppress his neighbors" and in "hostility to peace and progress in Central America." The US State Department also demanded that all investments in Central America would also need be approved by the U.S. as a means to protect U.S. interests and to overthrow president Zelaya according to a French minister.

The U.S. started giving aid to his Conservative and Liberal opponents in Nicaragua who broke out in open rebellion in October 1909, led by Liberal General Juan J. Estrada. Nicaragua sent its forces into Costa Rica to suppress Estrada's pro U.S. destabilizing forces, but U.S. officials deemed the incursion as an affront to Estrada's aims and attempted to coerce Costa Rica into acting first against Nicaragua, but Foreign Minister Ricardo Fernández Guardia assured Calvo that Costa Rica was determined "not to enter such dangerous actions as those proposed by Washington." It "considered the joint action proposed contrary to the Washington treaty and desired to maintain a neutral attitude." Costa Rican officials considered the United States a more serious threat to Central American peace and harmony than Zelaya's Nicaragua. Costa Rica Foreign Minister Fernández Guardia insisted, "We do not understand here what interests can the Washington government have that Costa Rica assumes a resolutely aggressive position against Nicaragua, with the danger of compromising the observation of the... conventions of December 20, 1907.... It is in Central America's interest that U.S. action with respect to Nicaragua should assume the character of an international conflict and in no sense the character of an intervention tolerated and even less solicited or supported by the other signatory republics of the Washington Treaty.

In historian Juan Jose Arevalo book titled The Shark and the Sardines, Juan noted:

From April 1908 the United States kept, off the coasts of Nicaragua on the Atlantic, a squadron made up of the cruisers Washington, Colorado, South Dakota, and Albany, and other smaller units, with a total contingent of four thousand men. These men -- better said, their officers -- had instructions to take advantage of the first opportunity to intimidate the arrogant and uncooperative president. In the city of Bluefields, overlooking the squadron, there was a State Department representative with precise orders about the situation: Consul Thomas Moffat. This professor of psychology, in that chapter of psychology that could be called the "Sewers of Psychology" or the "Psychology of the Sewers" found some Nicaraguans who were making talk about country and freedom -- men who were enemies of Zelaya and admirers of Wall Street. Consul Moffat, professor of mathematics in the chapter of mathematics applying to gastronomy -- that is, the chapter limited to giving the ciphers for eating today, for eating tomorrow and for eating day after tomorrow -- made the first dollars drop into the limp pocketbooks of the men opposed to Zelaya and was thus able to prove that psychology and mathematics have a common root. In the same way, he was able to prove that in the consciences of certain men, the sentiment of patriotism vibrates at the same wave length as a one-hundred dollar bill and that the two are woven into the same emotions regarding the future, progress and freedom. Such Nicaraguan "patriots" were willing to do anything, just in order to be able to govern Nicaragua and administer the affairs of Nicaragua, i.e., to be the ones to carry out the buying and selling transactions. The most important one on the team was Adolfo Diaz, empty headed as a drum, who was employed at a salary of eighty dollars a month, as bookkeeper in the La Luz and Los Angeles Mining Company. Another of the leaders was Emiliano Chamorro, surly, disagreeable member of the Conservative Party, an opponent of no civic feeling and no moral standards other than his ambition. These two negotiated the complicity and treason of Nicaragua's military governor on the Atlantic Coast -- General Juan José Estrada, to whom the Presidency or administration of the country was offered as reward. With these three "patriots" at the head of Zelaya's enemies, the Yankee squadron believed they could spare themselves the physical unpleasantness of a landing operation. The Nicaraguans would "settle the problem for themselves." Of course, those Nicaraguans were authorized to use -- and did use -- the Stars and Stripes. When the rebel action began on October 10, 1909, Adolfo Diaz contributed six hundred thousand dollars. . . . On September 9, 1912, Estrada confessed to THE NEW YORK TIMES the origin of this money: he had been given a million dollars by the Yankee companies located in Nicaragua; two hundred thousand dollars from the firm of Joseph Beers and one hundred fifty thousand dollars from Samuel Weil. Ships of the United Fruit Company carried men and ammunition for the "liberators." Between the big oceangoing cruisers and the shore, two little warships moved about, lending service as "intelligence" -- the Dubuque and the Paducah. Two Yankee citizens were taken prisoner for exploding a dynamite bomb just as the Nicaraguan military transport was coming down the San Juan River. After they confessed, these two foreign delinquents were shot by a firing squad. Their execution provided a glorious new pretext for the men who were acting in the State Department's farce. They expelled Zelaya's diplomatic representative from Washington, and they declared diplomatic relations severed with the legitimate government of Nicaragua. Mister Knox, Secretary of State and legal adviser to the Fletcher family, who, by pure coincidence, were owners of mineral exploitations in Nicaragua (among them La Luz and Los Angeles Mining Company) said in the expulsion note: The government of the United States is convinced that the ideals and the will of the majority of the Nicaraguans are represented by the present revolution more faithfully than by the government of President Zelaya.

Officers of Zelaya's government executed some captured rebels; two United States mercenaries were among them, and the U.S. government declared their execution grounds for a diplomatic break between the countries which later lead to formal intervention. At the start of December, United States Marines landed in Nicaragua's Bluefields port, supposedly to create a neutral zone to protect foreign lives and property but which also acted as a base of operations for the anti-Zelayan rebels. On 17 December 1909, Zelaya turned over power to José Madriz and fled to Spain. Madriz called for continued struggle against the mercenaries, but in August 1910 diplomat Thomas Dawson obtained the withdrawal of Madriz. Thereafter the U.S. called for a constituent assembly to write a constitution for Nicaragua and the vacant presidency was filled by a series of Conservative politicians including Adolfo Diaz. The U.S. Marines remained stationed in Nicaragua until 1932, with one brief withdrawal in 1925. They also supervised several Nicaraguan elections; during this time, though free trade and loans, the U.S. exercised strong control over the country.