<Back to Index>

- Astronomer Edmond Halley, 1656

- Composer Friedrich Wilhelm Michael Kalkbrenner, 1785

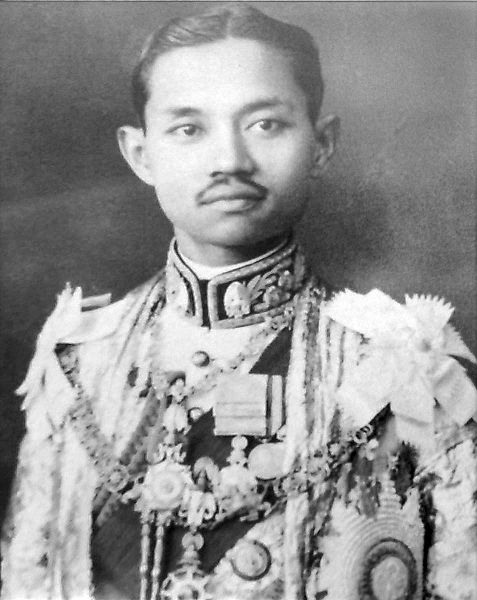

- King of Siam Rama VII, 1893

PAGE SPONSOR

Phra Bat Somdet Phra Poramintharamaha Prajadhipok Phra Pok Klao Chao Yu Hua (Thai: พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรมินทรมหาประชาธิปกฯ พระปกเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว), or Rama VII (8 November 1893 – 30 May 1941) was the seventh monarch of Siam under the House of Chakri. He was the last absolute monarch and the first constitutional monarch of the country. His reign was a turbulent time for Siam due to huge political and social changes during the Revolution of 1932. Also he was the only Siamese monarch to abdicate.

Somdet Chaofa Prajadhipok Sakdidej was born on 8 November 1893 in Bangkok, Siam (now Thailand) to King Chulalongkorn and Queen Saovabha Bongsri. Prince Prajadhipok was the youngest of nine children born to the couple, but overall he was the King's second youngest child (of a total of 77), and the 33rd and youngest of Chulalongkorn's sons.

Unlikely to succeed to the throne, Prince Prajadhipok chose to follow a military career. Like many of the King's children, he was sent abroad to study, going to Eton College in 1906, then to the Woolwich Military Academy from which he graduated in 1913. He received a commission in the Royal Horse Artillery in the British Army based in Aldershot. In 1910 Chulalongkorn died and was succeeded by Prajadhipok's older brother (also a son of Queen Saovabha), Crown Prince Vajiravudh, who became King Rama VI. Prince Prajadhipok was by then commissioned in both the British Army and the Royal Siamese Army. With the outbreak of the First World War and the declaration of Siamese neutrality, King Vajiravudh ordered his younger brother to resign his British commission and return to Siam immediately, a great embarrassment to the Prince who wanted to serve with his men on the western front. Once home, Prajadhipok became a high ranking military official in Siam. In 1917 was ordained temporarily as a monk, as is customary for all Siamese men.

In August 1918 Prince Prajadhipok married his childhood friend and cousin Mom Chao Rambhai Barni, a descendant of King Mongkut (Prajadhipok's grandfather) and his Royal Consort Piam. They were married at the Bang Pa-In Royal Palace with the blessing of the King.

After the war in Europe ended, he attended the École Superieure de Guerre in France, returning to Siam to the Siamese military. During this time, he was granted the additional title Krom Luang Sukhothai (Prince of Sukhothai). Prajadhipok lived a generally quiet life with his wife at their residence, Sukhothai Palace,

next to the Chao Phraya River. The couple had no children. Prajadhipok

soon found himself rising rapidly in succession to the throne, as his

brothers all died within a relatively short period. In 1925, King Vajiravudh himself died at the age of 44. Prajadhipok became absolute monarch at only

thirty-two. He was crowned King of Siam on 25 February 1926.

As monarch, Prajadhipok was referred to by his reigning name of Phrabat Somdet Phra Pokklao Chao Yuhua (พระบาทสมเด็จพระปกเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว) and in legal documents was a more formal Phrabat Somdet Phra Poraminthramaha Prajadhipok Phra Pokklao Chao Yuhua (พระบาทสมเด็จพระปรมินทรมหาประชาธิปก พระปกเกล้าเจ้าอยู่หัว)

Thais today usually call him Ratchakan thi Chet (lit. 'The Seventh Reign') or more colloquially, Phra Pok Klao (พระปกเกล้า), and in English, King Rama VII.

The system of referring to Chakri rulers as Rama (followed by a number)

was instituted by King Vajiravudh to follow European practice.

Relatively unprepared for his new responsibilities, Prajadhipok was nevertheless intelligent, diplomatic in his dealings with others, modest and eager to learn. However, he had inherited serious problems from his predecessor. The most urgent of these problems was the economy. The budget was heavily in deficit, and the royal financial accounts were a nightmare. The entire world was in the throes of the Great Depression.

Within

half a year only three of Vajiravhud's twelve ministers were still

serving the new King, the rest having been replaced by members of the

royal family. While the family appointments brought back men of talent

and experience, they also signalled a return to royal oligarchy. The

King clearly wished to demonstrate a clear break with the discredited

sixth reign, and his choice of men to fill the top positions appeared

to be guided largely by a wish to restore a Chulalongkorn type

government.

In

an institutional innovation intended to restore confidence in the

monarchy and government, Prajadhipok, in what was virtually his first

act as King, announced the creation of the Supreme Council of the State of Siam.

This privy council was made up of a number of experienced and extremely

competent members of the royal family, including the former

long serving Minister of the Interior (and King Chulalongkorn's right

hand man), Prince Damrong Rajanubhab.

Gradually these princes arrogated power to themselves, monopolising all

the main ministerial positions and appointing sons and brothers to both

administrative and military posts. Many of them felt it was their duty

to make amends for the mistakes of the previous reign, but their acts

were not generally appreciated, for the government failed to

communicate to the public the purpose of the policies they were

pursuing to rectify Vajiravhud's financial extravagances.

Unlike his predecessor, the king diligently read virtually all state papers that came his way, from ministerial submissions to petitions by citizens. The king was painstaking and conscientious; he would elicit comments and suggestions from a range of experts and study them assiduously, noting the good points in each submission, but when various options were available he would seldom be able to select one and abandon others. He would often rely upon the Supreme Council to persuade him in a particular direction.

In 1932, with the country deep in depression, the Supreme Council opted to introduce cuts in official spending, civil service pay rolls and the military budget. The King foresaw that these policies might create discontent, especially in the army, and he therefore convened a special meeting of officials to explain why the cuts were necessary. In his address he stated the following:

I

myself know nothing at all about finances, and all I can do is listen

to the opinions of others and choose the best... If I have made a

mistake, I really deserve to be excused by the people of Siam.

No

previous monarch had ever spoken so honestly. Unfortunately, many

interpreted his words not as a frank appeal for understanding and

cooperation, but as a sign of his weakness and proof that the system of

rule of fallible autocrats should be abolished.

King Prajadhipok turned his attention to the question of future politics in Siam. Inspired by the British example, the King wanted to allow the common people to have a say in the country's affairs by the creation of a parliament. A proposed constitution was ordered to be drafted, but the King's wishes were rejected by his advisers. Foremost among them were Prince Damrong and Francis B. Sayre, Siam's adviser in foreign affairs, who felt that the population was politically immature and not yet ready for democracy - a conclusion also reached, ironically, by the promoters of the People's Party.

However, spurred on by agitation for radical constitutional change, the King in 1926 began moves to develop the concept of prachaphiban, or 'municipality', which had emerged late in the fifth reign as a law regarding sanitation. Information

was obtained regarding local self - government in surrounding countries,

and proposals to allow certain municipalities to raise local taxes and

manage their own budgets were drawn up. The fact that the public was

not sufficiently educated to make the scheme work militated against the

success of this administrative venture. Nevertheless, the idea of

teaching the Siamese concept of democracy through a measure of

decentralisation of power in municipalities had become, in

Prajadhipok's mind, fundamental to future policy making. Before practical steps could be taken, however, the absolute monarchy was suddenly brought to an end.

A small group of soldiers and civil servants began secretly plotting to bring constitutional government to the kingdom. Their efforts culminated in the almost bloodless "revolution" on the morning of 24 June 1932 by the self - proclaimed People's Party (Khana Ratsadorn - คณะราษฎร). While Prajadhipok was away at Klaikangworn Palace in Hua Hin, the plotters took control of the Ananda Samakhom Throne Hall in Bangkok and arrested key officials (mainly the princes). The People's Party demanded Prajadhipok become a constitutional monarch and grant the Thai people a constitution. He immediately accepted and the first "permanent" constitution was promulgated on 10 December.

Prajadhipok's

return to Bangkok on 26 June dispelled any thoughts the plotters may

have had of proclaiming a republic. One of his first acts was to

receive the leading coup plotters in a royal audience. As they entered

the room, Prajadhipok greeted them, saying "I rise in honour of the

Khana Ratsadorn." It

was a very significant gesture. By Siamese tradition, monarchs remained

seated while their subjects made obeisance. Prajadhipok was

acknowledging the changed circumstances.

The King's relations with the People's Party deteriorated quickly, particularly after the ousting of Phraya Manopakorn Nititada as Prime Minister by the Khana Ratsadon's leader Phraya Phahol Phonphayuhasena.

In October 1933 the maverick Prince Boworadej, a popular former Minister of Defence who had resigned from Prajadhipok's cabinet in protest over the budget cuts, led an armed revolt against the government. In the Boworadet Rebellion, he mobilised several provincial garrisons and marched on Bangkok, occupying the Don Muang aerodome. Prince Boworadej accused the government of being disrespectful to the monarch and of promoting communism, and demanded that government leaders resign. Boworadej had hoped that garrisons in the Bangkok would support him, but their commander ensured that they remained loyal to the government. The Royal Thai Navy declared itself neutral and left for its bases in the south. After heavy fighting near Don Muang, the ammunition short Boworadej forces were defeated and the Prince himself fled to exile in French Indochina.

There is no evidence that Prajadhipok gave any support to the rebellion.

Nevertheless, the insurrection diminished the King's prestige. When the

revolt began, Prajadhipok immediately informed the government that he

regretted the strife and civil disturbances. The royal couple then took

refuge at Songkhla, in the far south. The king's withdrawal from the

scene was interpreted by the Khana Ratsadorn as a failure to do his

duty. By not throwing his full support behind the government's forces,

he had undermined their trust in him.

In 1934 the Assembly voted to amend the civil and military penal codes. One of the proposed changes would allow death sentences to be carried out without the King's approval. The King protested, and in two letters submitted to the Assembly said ending this time - honoured custom would make the people think that the government desired the right to sign death warrants to eliminate political opponents. As a compromise he proposed holding a national referendum on the issue. Many in the Assembly were angered. They felt the King was implying that the Assembly did not actually represent the will of the people and voted to re-affirm the penal code changes.

Prajadhipok,

whose relations with the Khana Ratsadorn had been deteriorating for

some time, went on a tour of Europe before visiting England for medical

treatment. He continued to correspond with the government, centring on

the conditions under which he would continue to serve. As well as

retaining some traditional royal prerogatives, such as granting

pardons, he was anxious to mitigate the increasingly undemocratic

nature of the new regime. Agreement

was reached on the penal codes, but Prajadhipok indicated he was

unwilling to return home before certain guarantees were made for his

safety, and the constitution was amended to make the Assembly an

entirely elected body. The government refused to comply, and on 14

October Prajadhipok announced his intention to abdicate unless his

requests were met.

The People's Party rejected the ultimatum, and on 2 March 1935, Prajadhipok abdicated to be replaced by Ananda Mahidol. Prajadhipok issued a brief statement criticising the regime that included the following phrases, since often quoted by critics of Thailand's slow political development:

I am willing to surrender the powers I formerly exercised to the people as a whole, but I am not willing to turn them over to any individual or any group to use in an autocratic manner without heeding the voice of the people.

As an idealistic democrat, the former king had good grounds for complaint. The Executive Committee and Cabinet did not seem eager to develop an atmosphere of debate or to be guided by resolutions of the Assembly.

Reaction

to the abdication was muted. Everybody was afraid of what might happen

next. The government refrained from challenging any assertions in the

King's abdication statement for fear of arousing further controversy.

Opponents of the government kept quiet because they felt intimidated

and forsaken by the King whom they regarded as the only person capable

of standing up to the promoters. In other words, the absolutism of the

monarchy had been replaced by that of the People's Party, with the

military looming in the wings as the ultimate arbiter of power.

He spent the rest of his life with Queen

They moved again to Vane Court, the oldest house in the village of Biddenden in Kent. He led a peaceful life there, gardening in the morning and writing his autobiography in the afternoon. In 1938 the royal couple moved to Compton House, in the village of Wentworth in Virginia Water, Surrey. Due to active bombing by the German Luftwaffe in 1940, the couple again moved, first to a small house in Devon, and then to Lake Vyrnwy Hotel in Powys, Wales, where the former king suffered a heart attack. The couple returned to Compton House, as he expressed his preference to die there. King Prajadhipok died from heart failure on 30 May 1941.

His cremation was held at the Golders Green Crematorium in

North London. It was a simple affair attended by just Queen Ramphai and

a handful of close relatives. Queen Ramphaiphanni stayed at Compton

House for a further eight years before she returned to Thailand in

1949, bringing the King's ashes back with her.

Written only up to the point when he was 25, the King's autobiography was left unfinished.

Among

the recent Chakri monarchs, particularly Chulalongkorn and Bhumibol,

Prajadhipok emerged with relatively little revisionistic detraction. He

was a hard working, effective administrator who was intellectually

equal to the demands of his office, and whose main failing was to

underestimate the Bangkok elite's growing need for change. As late as

his death in exile, many, as the historian David K. Wyatt puts it,

"would have agreed with his judgement that a move towards democracy in

1932 was premature."