<Back to Index>

- Botanist Carl Peter Thunberg, 1743

- Painter Paul Signac, 1863

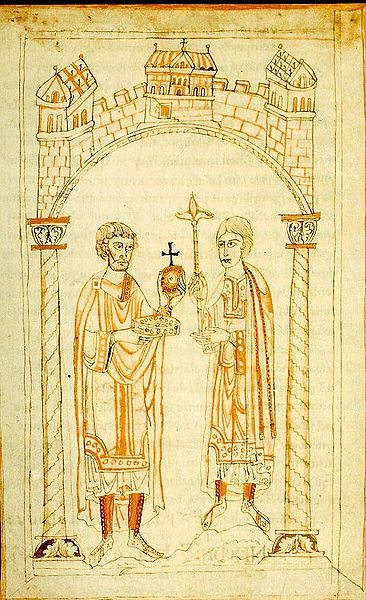

- Holy Roman Emperor Henry IV, 1050

PAGE SPONSOR

Henry IV (German: Heinrich IV) (11 November 1050 – 7 August 1106) was King of Germany from 1056 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1084 until his forced abdication in 1105. He was the third emperor of the Salian dynasty and one of the most powerful and important figures of the 11th century. His reign was marked by the Investiture Controversy with the Papacy and several civil wars with pretenders to his throne in Italy and Germany.

Henry was only six years old when he succeeded to the throne, and his mother, Agnes de Poitou, became regent, but in 1062 the young king was kidnapped as a result of a conspiracy of German nobles led by archbishop Anno II of Cologne. Henry, who was at Kaiserwerth, was persuaded to board a boat lying in the Rhine; it was immediately unmoored and the king jumped into the stream, but was rescued by one of the conspirators and carried to Cologne. Agnes retired to a convent, and the government was placed in the hands of Anno. His first move was to back Pope Alexander II against the antipope Honorius II, whom Agnes had initially recognized but subsequently left without support.

Anno's rule proved unpopular. The education and training of Henry were supervised by Anno, who was called his magister, while Adalbert of Hamburg, archbishop of Bremen, was styled Henry's patronus.

Henry's education seems to have been neglected, and his willful and

headstrong nature developed under the conditions of these early years.

The malleable Adalbert of Hamburg soon became the confidante of the

ruthless Henry. Eventually, during an absence of Anno from Germany,

Henry managed to obtain control of his civil duties, leaving Anno with

only the ecclesiastical ones. In

March 1065 Henry was declared of age. The whole of his future reign was

marked by apparent efforts to consolidate Imperial power. In reality,

however, it was a careful balancing act to maintain the loyalty of the

nobility and the support of the pope. In 1066, one year after his enthroning at the age of fifteen, he expelled Adalbert of Hamburg - Bremen,

who had profited from his position for personal enrichment, from the

Crown Council. Henry also adopted urgent military measures against the

Slav pagans, who had recently invaded Germany and besieged Hamburg. In June 1066 Henry married Bertha of Savoy / Turin, daughter of Otto, Count of Savoy,

to whom he had been betrothed in 1055. In the same year he assembled an

army to fight, at the request of the Pope, the Italo - Normans of

southern Italy. Henry's troops had reached Augsburg when he received news that Godfrey of Tuscany, husband of the powerful Matilda of Canossa, marchioness of Tuscany, had already attacked the Normans. Therefore the expedition was halted. In 1068, driven by his impetuous character and his infidelities, Henry attempted to divorce Bertha. His peroration at a council in Mainz was however rejected by the Papal legate Pier Damiani, who hinted that any further insistence towards divorce would lead the new pope, Alexander II,

to deny his coronation. Henry obeyed and his wife returned to Court,

but he was convinced that the Papal opposition aimed only at

overthrowing lay power within the Empire, in favour of an

ecclesiastical hierarchy. In

the late 1060s, Henry demonstrated his determination to reduce any

opposition and to enlarge the national boundaries. He led expeditions against the Lutici and the margrave of a district east of Saxony; and soon afterwards he had to quell the rebellions with Rudolf of Swabia and Berthold of Carinthia. Much more serious was Henry's struggle with Otto of Nordheim,

duke of Bavaria. This prince, who occupied an influential position in

Germany and was one of the protagonists of Henry's early kidnapping,

was accused in 1070 by a certain Egino of being privy to a plot to

murder the king. It was decided that a trial by battle should take

place at Goslar,

but when Otto's demand for safe conduct to and from the place of

meeting was refused, he declined to appear. He was thereupon declared

deposed in Bavaria, and his Saxon estates were plundered. However, he

obtained sufficient support to carry on a struggle with the king in

Saxony and Thuringia until 1071, when he submitted at Halberstadt. Henry aroused the hostility of the Thuringians by supporting Siegfried, archbishop of Mainz,

in his efforts to exact tithes from them; still more formidable was the

enmity of the Saxons, who had several causes of complaint against the

king. He was the son of one enemy, Henry III, and the friend of

another, Adalbert of Hamburg - Bremen. In

order to secure the Church's support for his expeditions in Saxony and

Thuringia, Henry adhered to Papal decrees in religious matters. His

apparent weakness, however, had the side effect of spurring the

ambitions of Gregory VII, a reformist monk elected as pontiff in 1073, toward Papal hegemony. The

tension between Empire and Church culminated in the councils of

1074 – 1075, which constituted a substantial attempt to undo Henry

III's

policies. Among other measures, they denied secular rulers the right to

place members of the clergy in office; this had dramatic effects in

Germany, where bishops were often powerful feudatories who, in this

way, were able to free themselves from imperial authority. In addition

to restoring all privileges lost by the ecclesiasticals, the council's

decision deprived the imperial crown of almost half its lands, with

grievous consequences for national unity, especially in peripheral

areas like the Kingdom of Italy. Suddenly

hostile to Gregory, Henry did not relent from his positions: after his

defeat of Otto of Nordheim, he continued to interfere in Italian and

German episcopal life, naming bishops at his will and declaring papal

provisions illegitimate. In 1075, Gregory excommunicated some members

of the Imperial Court and threatened to do the same to Henry himself.

Furthermore, in a synod held in February of that year, Gregory clearly

established the supreme power of the Catholic Church, with the Empire

subjected to it. Henry replied with a counter - synod of his own. The beginning of the conflict known as the Investiture Controversy can be assigned to Christmas night of 1075: Gregory was kidnapped and imprisoned by Cencio I Frangipane, a Roman noble, while officiating at Santa Maria Maggiore in

Rome. Later freed by the Roman people, Gregory accused Henry of having been

behind the attempt. In the same year, the king had defeated a rebellion

of Saxons in the First Battle of Langensalza, and was therefore free to accept the challenge. At Worms, on 24 January 1076, a synod of

bishops and princes summoned by Henry declared Gregory VII deposed.

Hildebrand replied by excommunicating the king and all the bishops

named by him on 22 February 1076. In October of that year a diet of the

German princes in Tribur attempted

to find a settlement for the conflict, conceding Henry a year to repent

from his actions, before the ratification of the excommunication that

the pope was to sign in Swabia some months later. Henry did not repent,

and, counting on the hostility showed by the Lombard clergy against

Gregory, decided to move to Italy. He left Speyer in December 1076, spent Christmas of that year in Besançon and, together with his wife and his son, he crossed the Alps with help of the Bishop of Turin and reached Pavia. Gregory, on his way to the diet of Augsburg, and hearing that Henry was approaching, took refuge in the castle of Canossa (near Reggio Emilia), belonging to Matilda. Henry's troops were nearby. Henry's

intent, however, was apparently to perform the penance required to lift

his excommunication and ensure his continued rule. The choice of an

Italian location for the act of repentance, instead of Augsburg, was

not accidental: it aimed to consolidate the Imperial power in an area

partly hostile to the Pope; to lead in person the prosecution of

events; and to oppose the pact signed by German feudataries and the

Pope in Tribur with the strong German party that had deposed Henry at

Worms, through the concrete presence of his army. He

stood in the snow outside the gates of the castle of Canossa for three

days, from 25 January to 27 January 1077, begging the pope to rescind

the sentence (popularly portrayed as without shoes, taking no food or

shelter, and wearing a hairshirt - see Walk of Canossa). The Pope lifted the excommunication, imposing a vow to comply with certain conditions, which Henry soon violated. Rudolf of Rheinfelden, a two - time brother - in - law of Henry along with allied German Aristocrats, took advantage of the momentary weakness of the king in what became known as the Great Saxon Revolt by having himself declared antiking by a council of Saxon, Bavarian, and Carinthian princes in March of 1077 in Forchheim. Rudolf promised to respect the electoral concept of the monarchy and declared his willingness to submit to the pope. Despite

these difficulties, Henry's situation in Germany improved in the

following years. When Rudolf was crowned king at Mainz in May 1077 by

one of the plotters, Siegfried I, Archbishop of Mainz,

the population revolted and forced him, the archbishop, and other

nobles to flee to Saxony. Positioned there, Rudolf was geographically

and then militarily deprived of his territories by Henry; he was later

stripped of Swabia as well. After the inconclusive battle of Mellrichstadt (7 August 1077) and the defeat of Henry's forces in the Flarchheim (27

January 1080) Gregory flip - flopped to support the revolt and launched a

second anathema (excommunication) against Henry in March 1080, thereby

supporting the anti - king Rudolph. However, the ample evidence that

Gregory's actions were rooted in hate for the Emperor - elect instead of

theology had an unfavourable personal impact on the Pope's reputation

and authority, leading much of Germany to return to Henry's cause. On 14 October 1080 the armies of the two rival kings met at the Weisse Elster River in the battle of Elster, in the plain of Leipzig and Henry's forces again suffered a military defeat, but won the battle with a strategic outcome — the anti - king Rudolf of Rheinfelden was mortally wounded and died the next day at nearby Merseburg, and the rebellion against Henry lost much of its momentum. Soon after, another anti - king, Hermann of Salm, arose as figurehead in the Great Saxon Revolt cause, but was fought successfully by Frederick I, Duke of Swabia (Frederick of Swabia) — Rudolf's Henry - appointed successor in Swabia who had married Henry's daughter Agnes of Germany. Henry convoked a synod of the highest German clergy in Bamberg and Brixen (June 1080). Here Henry had pope Gregory (he'd dubbed "The False Monk") again deposed and replaced by the primate of Ravenna, Guibert (now known as the antipope Clement III, though who was in the right was unclear in the day).

Henry entered Pavia and was crowned here as King of Italy, receiving the Iron Crown. He also assigned a series of privileges to the Italian cities who had supported him, and marched against the hated Matilda of Tuscany, declaring her deposed for lese majesty and

confiscating her possessions. Then he moved to Rome, which he besieged

first in 1081: he was however compelled to retire to Tuscany, where he

granted privileges to various cities, and obtained monetary assistance

(360,000 gold pieces) from a new ally, the eastern emperor, Alexios I Komnenos,

who aimed to thwart the Norman's aims against his empire. A second and

equally unsuccessful attack on Rome was followed by a war of

devastation in northern Italy with the adherents of Matilda; and

towards the end of 1082 the king made a third attack on Rome. After a

siege of seven months the Leonine City fell

into his hands. A treaty was concluded with the Romans, who agreed that

the quarrel between king and pope should be decided by a synod, and

secretly bound themselves to induce Gregory to crown Henry as emperor,

or to choose another pope. Gregory, however, shut up in Castel Sant' Angelo,

would hear of no compromise; the synod was a failure, as Henry

prevented the attendance of many of the pope's supporters; and the

king, in pursuance of his treaty with Alexios, marched against the

Normans. The Romans soon fell away from their allegiance to the pope;

and, recalled to the city, Henry entered Rome in March 1084, after

which Gregory was declared deposed and Clement was

recognized by the Romans. On 31 March 1084 Henry was crowned emperor by

Clement, and received the patrician authority. His next step was to

attack the fortresses still in the hands of Gregory. The pope was saved

by the advance of Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, who left the siege of Durazzo and marched towards Rome: Henry left the city and Gregory could be freed. The latter however died soon later at Salerno (1085), not before a last letter in which he exhorted the whole of Christianity to a crusade against the emperor. Feeling secure of his success in Italy, Henry returned to Germany. The

Emperor spent 1084 in a show of power in Germany, where the reforming

instances had still ground due to the predication of Otto of Ostia, advancing up to Magdeburg in Saxony. He also declared the Peace of God in all the Imperial territories to quench any sedition. On 8 March 1088 Otto of Ostia was elected pope as Victor III:

with Norman support, he excommunicated Henry and Clement III, who was

defined "a beast sprung out from the earth to wage war against the

Saints of God". He also formed a large coalition against the Holy Roman Empire, including, aside from the Normans, the Rus of Kiev, the Lombard communes of Milan, Cremona, Lodi and Piacenza and Matilda of Canossa, who had remarried to Welf II of Bavaria, therefore creating a concentration of power too formidable to be neglected by the emperor. In 1088 Hermann of Salm died and Egbert II, Margrave of Meissen,

a long - time enemy of the emperor's, proclaimed himself the antiking's

successor. Henry had him condemned by a Saxon diet and then a national

one at Quedlinburg and Regensburg respectively, but was defeated by Egbert when a relief army came to the margrave's rescue during the siege of Gleichen. Egbert was murdered two years later (1090) and his ineffectual insurrection and royal pretensions fell apart. Henry then launched his third punitive expedition in

Italy. After some initial success against the lands of Canossa, his

defeat in 1092 caused the rebellion of the Lombard communes. The

insurrection extended when Matilda managed to turn against him his

elder son, Conrad, who was crowned King of Italy at Monza in

1093. The Emperor therefore found himself cut off from Germany. He

could return there only in 1097: in Germany his power was still at its

height. Matilda of Canossa had secretly transferred her property to the

Church in 1089, before her marriage to Welf II of Bavaria (1072 – 1120).

In 1095, a furious Welf left her and, together with his father,

switched his allegiance to Henry IV, possibly in exchange for a promise

of succeeding his father as duke of Bavaria. Henry reacted by deposing

Conrad at the diet of Mainz in April 1098, and designating his younger

son Henry (future Henry V) as successor, under the oath sworn that he would never follow his brother's example. The situation in the Empire remained chaotic, worsened by the further excommunication against Henry launched by the new pope Paschal II,

a follower of Gregory VII's reformation ideals elected in the August of

1099. But this time the emperor, meeting with some success in his

efforts to restore order, could afford to ignore the papal ban. A

successful campaign in Flanders was followed in 1103 by a diet at

Mainz, where serious efforts were made to restore peace, and Henry IV

himself promised to go on crusade. But this plan was shattered by the

revolt of his son Henry in 1104, who, encouraged by the adherents of

the pope, declared he owed no allegiance to an excommunicated father.

Saxony and Thuringia were soon in arms, the bishops held mainly to the

younger Henry, while the emperor was supported by the towns. A

desultory warfare was unfavourable, however, to the emperor, who was

taken as prisoner at an alleged reconciliation meeting at Koblenz. At a diet held in Mainz in December, Henry IV was forced to resign his crown, being subsequently imprisoned in the castle of Böckelheim.

Here he was also obliged to say that he had unjustly persecuted Gregory

VII and to have illegally named Clement III as anti-pope. When

these conditions became known in Germany, a vivid movement of

dissension spread. In 1106 the loyal party set up a large army to fight

Henry V and Paschal. Henry IV managed to escape to Cologne from his

jail, finding considerable support in the lower Rhineland. He also entered into negotiations with England, France, and Denmark. Henry

was also able to defeat his son's army near Visé, in Lorraine,

on 2 March 1106. However, he died soon afterwards after nine days of illness, while he was the guest of his friend Othbert, Bishop of Liège. He was 56.

His body was buried by the bishop of Liege with suitable ceremony, but by command of the papal legate it was unearthed, taken to Speyer and placed in the unconsecrated chapel of Saint Afra that was built on the side of the Imperial Cathedral. After being released from the sentence of excommunication, the remains were buried in Speyer cathedral in August 1111.

Henry

IV was known for licentious behaviour in his early years, being

described as careless and self - willed. In his later life, he

displayed

much diplomatic ability. His abasement at Canossa can be regarded as a

move of policy to weaken the pope's position at the cost of a personal

humiliation to himself. He was always regarded as a friend of the lower

orders, was capable of generosity and gratitude, and showed

considerable military skill. Henry's wife Bertha died on 27 December 1087. She was also buried at the Speyer Cathedral. They had six children. In 1089 Henry married Eupraxia of Kiev (crowned Empress in 1088), a daughter of Vsevolod I, Prince of Kiev, and sister to his son Vladimir II Monomakh, prince of Kievan Rus.

She assumed the name "Adelaide" upon her coronation. In 1094, she

joined the rebellion against Henry, accusing him of holding her

prisoner, forcing her to participate in orgies, and attempting a black mass on her naked body.